Canceling Philip Roth in the Name of Progressive Neoliberalism?

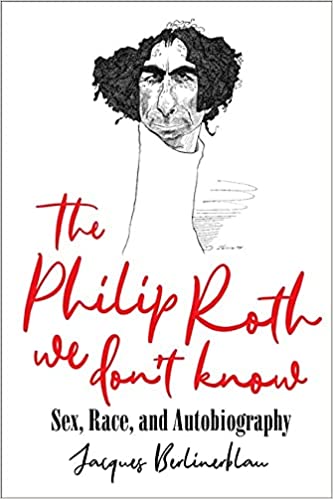

The Philip Roth We Don’t Know: Sex, Race, and Autobiography. Jacques Berlinerblau. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2021.

Canceling Philip Roth in the Name of Progressive Neoliberalism?

—A Review of Jacques Berlinerblau’s The Philip Roth We Don’t Know: Sex, Race, and

Autobiography (University of Virginia Press, 230 pages)

Since his death in 2018, Philip Roth has had quite a number of re-births as a topical public figure. Trump era readings of The Plot Against America, along with the HBO serializing of the same, have been added to by relevant discussions of what Roth’s last novel, Nemesis, a book about a polio epidemic, can tell us about the social, political, and psycho-emotional (or affective) implications of Covid 19 on the broader public. To add further to this mix, the release of a spate of Roth biographies in 2021 has been attended by no end of controversies, least of all in relation to W.W. Norton’s canceling of its publication of Blake Bailey’s authorized biography, in light of a series of accusations of sexual misconduct against the latter. It is into this breach that Jacques Berlinerblau’s new book steps, intent on righting a few wrongs in relation to what he sees as Roth’s dubious racial and sexual politics.

Inspired by the “new conversational intersection between #MeToo and the arts,” The Philip Roth We Don’t Know: Sex, Race, and Autobiography is sure to stir up all kinds of controversies, new and old, regarding the recently deceased Jewish author. Arriving amid the backdrop of intrigue and scandal provoked by recent Roth biographies, Berlinerblau sets out to write what he calls a “reverse biography,” by which he reads Roth’s fiction as revealing of acute racial and gender biases in both the personal life and published work of the author. What seems to define this experimental approach is the near alchemical genius of extracting from literary texts a fuller picture of the author’s biography (as made extant, for the most part, by recent biographies), while then using such an expanded understanding of the author, as living person, to read his body of work.

There is a peculiar tautology at work here that capsizes important distinctions between art and life. Since such circular reasoning allows for all kinds of wild claims about Roth, in particular, and the function of literature in general, it elicits an urgent need for some critical response. According to Berlinerblau’s logic, establishing the all-important through-lines between literary text and biographical world relies upon the courage of readers to undertake the pressing task of dismantling the formal “wall” that Roth has sought to construct in his novels and critical prose by fetishizing the aesthetic distance between fiction and fact. For Berlinerblau, fusty attention to this “Golden Rule of cultural analysis” concerning the distance that separates author and text needs to be called out because it is the privileged, self-exculpating property of white male artists like Roth.

The outcome of this critical method is a simplified idea of Roth’s “art/life loops,” by which flesh-and-blood author and imagined text meet full circle, sans any real sense of conflict, dissonance, or difficult formal mediation. In thus capsizing the space between the writer’s output and his life, Berlinerblau manages to flatten Roth’s body of writing to the moral apostasies of what he describes as a cringingly outmoded, “cis-gendered,” white male privileged has-been. Whatever about the potential merits of such claims, Berlinerblau’s support of them is founded upon a highly questionable method of reading that is deeply lacking in critical substance. Indeed, The Philip Roth We Don’t Know betrays what Tom Nichols’ The Death of Expertise calls a certain post-factual disdain for the ‘expert’ reasoning of scholarly and literary traditions by reverting instead to a politico-moral didacticism that relies chiefly on spurious textual evidence and a general tendency to avoid complex literary analysis.

Berlinerblau prophesies about the potential “demise of Roth’s legacy” in light of “the types of concerns that #MeToo raises about male misbehavior.” What is perhaps most problematic here is that The Philip Roth We Don’t Know is so bent on calling out “immoral artists,” as defined by their personal lives, that it misses an awful lot in terms of Roth’s complex literary engagement with questions of history and social power, particularly as pertaining to such things as class, race, and gender. Berlinerblau seeks to obfuscate such literary nuance and drown out debate by making dramatic statements regarding “Roth’s men” as “epaulet-bearing brand ambassadors of ‘rape culture.’” At other stages, he argues that “the charge of misogyny [against Roth] becomes hard to avoid” in light of how the author “abduction-vanned former girlfriends and wives into that odd safe house that was his fiction.” As Berlinerblau knows only too well, the current zeitgeist, particularly as it finds expression through Roth biographical scandals, means that such graphic language and sensational charges will go largely unquestioned, since those brave enough to query Berlinerblau’s wild assumptions may end up tarred with the same stain of prejudice and bigotry that he applies to Roth. Yet ironically, this zero-sum game of executional moral cleansing comes to haunt Berlinerblau himself. It becomes quickly clear while reading The Philip Roth We Don’t Know that this lightly researched book (despite its peer-reviewed status) is in fact exploiting for its own commercial purposes, without effectively contributing to, a broader progressive environment that is struggling to tackle sensitive issues of sexual harassment, misogyny, and gender inequality.

The chief irony of Berlinerblau’s gleeful expose of Roth’s ‘reactionary’ tendencies is that it betrays its own neoliberal, market-value take on such things as gender and race. Berlinerblau’s historical imagination falls foul of what feminists like Nancy Fraser and black intellectuals like Toure Reed define as a reified ‘culturalist’ perspective concerning the ahistorical immanence of ‘identity’—an essentialism of the marginalized that is, ironically, complicit in the neoliberal structuring of racial and gender inequalities. By taking this quick and easy path of appeal to the voguish sentiments of certain readers, Berlinerblau’s reductive view of Roth’s politics misses so much in relation to the latter’s engagement with the social, ideological, and materialist underpinnings of a neoliberal political economy that has structured prejudice, exploitation, and inequality in America over the past fifty-plus years. Dismissing such relevancies, Berlinerblau’s scholarship represents the apotheosis of a kind of didactic literary scholarship and ahistoricist, content-less ‘leftism’ that Richard Rorty once labeled “spectatorial,” and which Roth’s The Human Stain reveals as central to the ideological propagation on American campuses of what Fraser calls “progressive neoliberalism.”

Unafraid to personalize matters, Berlinerblau makes repeated allusions to the difficulties that Roth presents to younger generations of undergraduate students, particularly those who attend his classes at Georgetown University. By asking how we might find a “way of selling him [Roth] to the current generation, where he is often seen as just another White Guy who prose-ogled women’s bodies,” Berlinerblau readily dismisses the informed opinions of other Roth readers, ranging from Zadie Smith to Harold Bloom, while assuming a monopoly of scholarly authority for both himself and undergraduate students at the expensive, elite university where he teaches. Such a move is uncannily reminiscent of the academic sycophancy of Roth’s Delphine Roux (The Human Stain), whose burning desire for popularity among her students qua high-paying clients is indicative of a sensibility that pervades nearly all corners of American academia today, particularly the declining field of literary studies and its financially concerned departments of English.

The Philip Roth We Don’t Know betrays its own academic class privileges by continually trumpeting its self-heroizing moral coherence regarding what are, in fact, complex contemporary issues of race and gender, particularly as they are shaped by a bruising world of neoliberal political economy and its monstrous populist variations under the likes of Trump. It is Roth’s fiction and its significant ripostes to American forms of class, racial, and (yes) gender exploitation that are sacrificed at the altar of Berlinerblau’s self-capitalizing virtue. Berlinerblau’s book is thus part of the broader cultural arsenal of what left-wing scholar, Catherine Liu calls the professional managerial class of Virtue Hoarders, whose tendencies to “weaponize outrage” and “moral panic” over cultural apostates like Roth betrays so much about how “they [themselves] are unable and unwilling to face their identity as a class.” Or, as The Human Stain’s Coleman Silk—a character whose Hayekian conception of selfhood is seriously compromised by the formal, dialogical examinations of issues of class, race, gender, and literary scholarly debate within Roth’s novel—might quip, this “reverse biography” of Roth is “just the latest mouthwash,” designed so that middle-brow readers and sensitized student consumers can get rid of that bad taste that Roth has left in their mouths.

The inquisitional infallibility of this reverse-biographical framework is premised by Berlinerblau’s presumption to be able, like a sooth-sayer of old, to locate Roth’s (im)moral center from within the refracted voices of disparate novelistic characters. By taking this approach, his study obliterates the differences between myriad Roth characters, only then to reduce almost all distance between the author and those invented subjects who speak in his novels. However, such a brutalist method for establishing, in a pure ideological or theological sense, the moral credentials of literature leaves room for us to say just about anything we want about the political loyalties and betrayals of Roth, or any other novelist or artist for that matter.

In response to all this fanatical weaponizing of fiction, I would suggest that Roth puts his characters and their sentiments under much greater critical stress than Berlinerblau allows. Such complexity is evidenced by the ways in which Roth places his characters and narrators in dialogical interaction—or narrative tension—with each other. This is a formal arrangement of diverging and converging social perspectives that, as the great leftist-formalists, Mikhail Bakhtin and V. I. Volosinov inform us, is typical of all narratives (of course, F. R. Leavis, John Crowe Ransom, and Lionel Trilling add their own clout to this view of literature as the terrain of irony and ambiguity, while Edward Said, Henry Gates, Gayatri Spivak, and Fredric Jameson have long taken this issue of literary form further by thinking of it in relation to such things as class, race, gender, and post-colonial identity). Such perspectival uncertainty holds utmost validity when it comes to indirect discourse, narrative framing, and dramatic plot in the works of authors like Roth, or indeed Toni Morrison, Edith Wharton, Henry James, and James Joyce. So, all that high-aesthetic stuff that Berlinerblau wants to strip away by getting to the onion-core of his “reverse biography” is not just excess trapping or elite male privilege. It’s simply a rudiment of literature and its untold, albeit socially interpretable variations on a subject or theme, whether it be race, gender, sexuality, a pandemic (see Roth’s Nemesis), or large insects (see Kafka’s “Metamorphosis”).

His insistent desire to talk about race and gender without thinking about how such social issues are conditioned by powerful historical forces reflects Berlinerblau’s neoliberal, end of history view of difference and identity—a post-historicism that is completely blown apart by Roth’s thoughtful considerations about the past and history as the unsteady site of the “relentless unforeseen.” The Philip Roth We Don’t Know thus commits to what Reed calls a two-dimensional form of race reductionism that de-historicizes the specific struggles of black people. Not only does such a fetishized view of race avert attention from how questions of class and political economy structure the perverse dyads of privilege and dehumanization in America. It also reveals, as Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor illustrates, a white American liberal view of race that is all too amenable to a neoliberal corporatist understanding of diversity without social conflict—cultural recognition without economic re-distribution.

All of this tokenizing of social justice without the messiness of material historical conflict and struggle is a perfect fit for universities that have a high-end product to sell to high-end customers. As Berlinerblau remarks, a chief social concern of his is that he never-ever wants to “turn-off” his ‘valuable’ students by getting them to consider the social realism of a cartoon villain like Roth, as he is constructed for us in the pages of this book, as well as in other gossipy chambers of biographical intrigue. As The Philip Roth We Don’t Know asks more than once, how can a well-paid professor go about “selling” Roth to twenty-first century students? Well, maybe selling people an education at a very lucrative price is part of the problem.