Cormac McCarthy’s Coda: The Last Breath Of An Agnostic Materialist

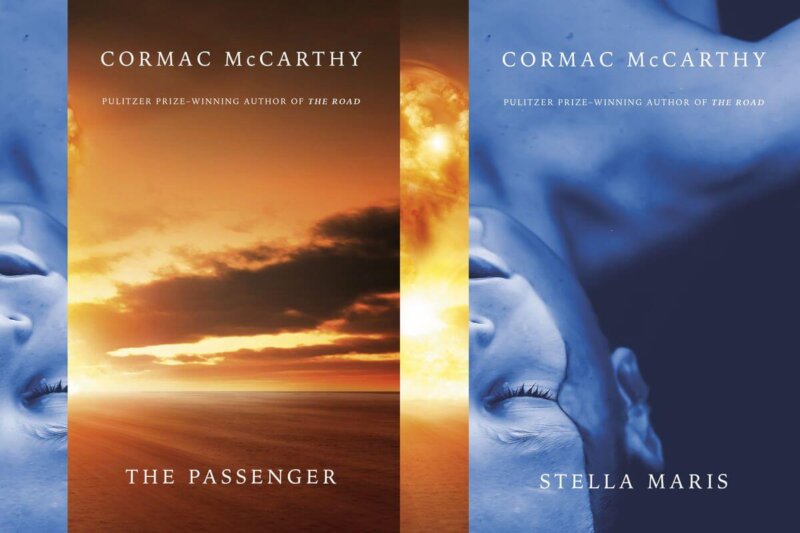

The greatest living author in the United States passed away last month on June 13. Cormac McCarthy died of natural causes at the age of 89, having given readers of the English language over a 57-year literary career with 12 published novels, many of them profoundly insightful and mesmerizing, even if bleak. But before departing this life, he published his final two books—The Passenger on October 25, 2022 and Stella Maris on December 6—offering a final coda to this career. McCarthy began as a fledgling literary genius attempting to become the next William Faulkner before turning the Southern Gothic genre on its head with some of its most brutal and sorrowful tales yet conceived.

Last November, the usually misanthropic author gave a rare podcast interview to theoretical physicist Lawrence Krauss—a celebrity anti-theist and former science advisor to President Barrack Obama. Krauss did most of the talking, which wasn’t surprising, but the few words that the aging novelist could get in were surprising. It turns out McCarthy’s great passion in life wasn’t writing but physics, and that he had spent the last few decades of his spare time reading up on the latest developments in science and mathematics.

Amid the conversation, McCarthy made a curious admission when asked by Krauss if he believed in God. In his most recent book, two characters discuss the possibility of life after death and intelligent design, which the celebrity anti-theist found unassuming. McCarthy rebuked Krauss, arguing that his characters do not represent his opinions and saying, “I have to plead ignorance. I’m pretty much a materialist,” he says. “I’m not a believer in divine plans.”

To anyone who has read McCarthy’s books, it isn’t surprising that the author does not believe in God in any traditional sense. His works reflect a very dark and misanthropic view of modern life, exploring the total depravity of man and the seeming lack of injustice of a world that comes to murderers and villains who prey upon the innocent.

His argument to Krauss ultimately does speak to the philosophy the undergirds his most recent efforts, with his final two books offering a much more uncommitted and agnostic view of the universe than Krauss’s determined atheism. In these books, two of McCarthy’s most logical and complicated characters to date are left to contemplate life’s most difficult questions in the face of moral confusion and tragedy.

Both The Passenger and Stella Maris are thoroughly modern novels, in the sense that they’re both episodic pastiches centered around largely plotless digressions on humanity, philosophy, and heady neurotic-self reflection—which is not to say they’re bad. But McCarthy was certainly wise to point out to Krause that his characters do not represent his opinions. Despite the best attempts of modern critics to push Neo-Freudianism pop psychoanalysis and read characters as autobiographical avatars of their authors, McCarthy reminds us we ultimately can’t gleam too much autobiographical detail from the career of an artist whose regular themes involved murder, suicide, necrophilia, cannibalism, and genocide.

Regardless, his final duology consists of uniquely profound novels, in that they do offer readers the experience of grappling with some of the densest, most confounding, and unsettling themes of McCarthy’s career, giving readers a lengthy dialogue-heavy meditation on death, lust, mathematics, religion, insanity, conspiracy theories, nuclear armageddon, and humanity’s vain grasping for narrative clarity in a world that seems to imply something greater and more nefarious is brewing just beyond our sights—that we may never understand.

The books follow the lives of Robert and Alicia Western, the children of a scientist who worked for physicist J. Robert Oppenheimer on the atomic bomb, before their family moved to rural Eastern Tennessee. Both of the Western children are brilliant college dropouts who share a passion for physics and mathematics. And they have also been madly and incestuously in love with one another, but have become estranged by the time both novels begin. Both are unreliable narrators, claiming that their opposite sibling is dead or otherwise indisposed, but this is an attempt to bury the painful truths and temptations of their pasts.

The Passenger follows Robert through a long and episodic story of conspiracies and coincidences happening around him that he can neither understand nor solve. At the outset of his story, while working as a salvage diver, he discovers a crashed airplane in the swamps of Mississippi with a missing passenger on the flight manifest.

His proximity to the underwater crash draws the scrutiny of strange government agents who suspect he knows something more than he is telling, but he doesn’t. Western is not proactive enough to figure out what is happening to him but doesn’t lack the understanding to realize that his life is spinning out of control as people start slowly dying around him and his bank accounts are closed on wrongful suspicion of tax fraud.

Alternatively, in Stella Maris, Alicia is revealed to be far too aggressively proactive. She is burdened with one of the most cold and logical minds of any character in contemporary fiction, but also burdened with severe schizophrenia and depression. She is so smart that nobody around her can provide her a logical reason why suicide isn’t rational.

Unfortunately, the only event that the books seem to make solid is her death. The prologue of The Passenger begins with a description of her suicide, supplanting this as the moral core and inciting event of both books, even if the second book is a prequel comprised entirely of therapy recordings from while she was staying at the Stella Maria Mental Asylum in Black River Falls, Wisconsin in the 1970s.

It’s hard to describe the structure of these books because their lack of structure is at the root of its thematic point. These are stories about irresolution—about the inability to find narrative fulfillment in the universe and the frustration of living a life where the big questions of life have no answers. Narrative frustration is the ultimate point of both novels. There is no secret to be revealed about the mysterious flight and missing passenger. There is no government conspiracy to uncover. There is to be no therapeutic breakthrough and healing. There is only the sense that something massive and horrific is happening, somewhere away from prying eyes.

The duology can only posit a radical agnosticism, leaving its characters alone and in pain as they contemplate their place in the universe and the meaning of their imminent deaths.

The core incestuous romance of Alicia and Bobby raises many of the book’s most difficult questions and harsh implications. As one character reflects, “When smart people do dumb things it’s usually due to one of two things. The two things are greed and fear. They want something they’re not supposed to have or they’ve done something they weren’t supposed to do. In either case they’ve usually fastened on to a set of beliefs that are supportive of their state of mind but at odds with reality. It has become more important to them to believe than to know.”

Despite their incredible propensity towards rationalism, the Western siblings find themselves caught in a forbidden romance that Bobby is wise enough to know not to indulge, although he finds himself regretting that he didn’t on his death bed as he prays to a God he doesn’t believe in. Alicia is even more harshly disturbed by her feelings. She tells her therapist in Stella Maris that her love, her desire to run away, marry, and conceive a child with her brother, has completely crippled her life. She still loved him until her suicide, and knew she would never love another man again.

“I just hoped he would come to his senses. That he would suddenly come to understand what he’d always known. I supposed I thought to shock him out of his complacency. I would hold his hand. I’d sit close against him driving home and put my head on his shoulder. I suppose I was shameless but then shame was not something I was really concerned with. I knew that I had only one chance and one love. And I wasn’t wrong about his feelings.”

McCarthy doesn’t offer many answers or much consolation through either book. He actively eschews traditional narrative in favor of lengthy digressions of his characters meditating on the nature of physics or Neoplatonic philosophy. What little hope both characters have about the future comes in the vain hope that science can advance the status of mankind, but being the children of nuclear weapons scientists leaves them with significant doubt of that possibility.

In a career with books as bleak and violent as Blood Meridian and No Country For Old Men to his name, his final two novels don’t quite shock so much as ruminate. The Passenger has been a novel McCarthy worked on intermittently since the 1970s and marked his first published book since The Road in 2007. He chose a very opaque and sad story to conclude his career on, giving readers his most difficult ideas to meditate on before his characters’ lives are snuffed out quietly, like candles.

Given all they’ve seen, the Westerns have little hope either in earthly scientific progress or in an afterlife, but neither character is confident enough to disbelieve completely in either. The total unknowability of the universe doesn’t disregard the possibility of hope, even if neither sibling wants it. In some sense, the Westerns are also a reflection of Cormac McCarthy himself.