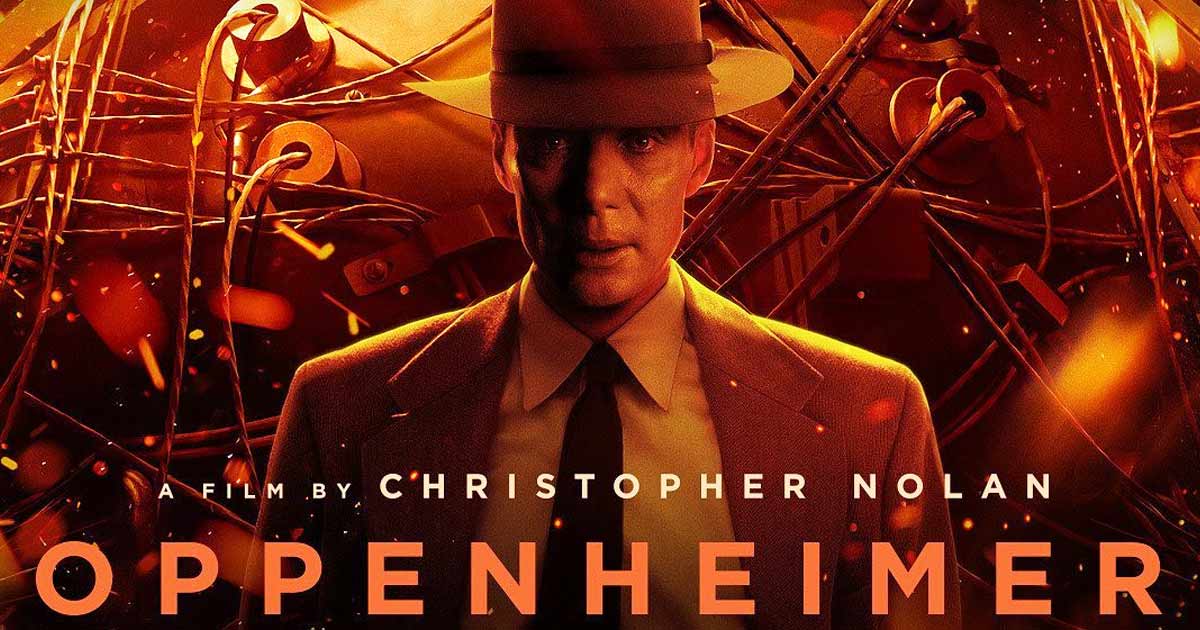

Jesse Russell is an Assistant Professor of English at Georgia Southwestern State University. He has contributed to a wide variety of academic journals, including Political Theology, Politics and Religion, and New Blackfriars. He also writes for numerous public journals and magazines, including University Bookman, Law & Liberty, and Front Porch Republic. He is the author of The Political Christopher Nolan: Liberalism and the Anglo-American Vision (Lexington Books, 2023).