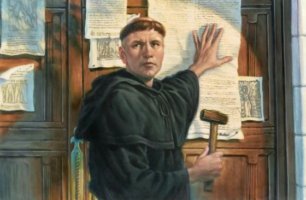

Was Eric Voegelin Fair to Martin Luther? Reflections on Voegelin’s treatment of Luther in the History of Political Ideas

Eric Voegelin’s treatment of Martin Luther in the History of Political Ideas (henceforth History; page references when not otherwise noted are to vol. IV of the History) is a tour de force in spirited and, indeed, angry writing. For those not familiar with this material, let us begin by giving some examples:

Firstly, the chapter devoted to Luther and Calvin is entitled “The Great Confusion”, in itself something of an indication of what is to come.2 Early on in the text, to describe the debates between Luther, the Hussites, Zwingli, and their adversaries Voegelin says that the “conversio had sunk to the level of a pseudometaphysical squabble between intellectuals who did not master the issue” (p. 227). Later in the discussion we find such fiery descriptions of Luther and his movement as “this nightmare of nonsense” (p. 236); “this peculiar blindness” (p. 239); “this impossible Reformation” (p. 245); “probably the biggest piece of political mischief concocted by a man, short of the Communist Manifesto” (ibid.); “[Luther’s] almost incredible lack of wisdom” (p. 247); “Luther did not possess the powers of intellect that enable a man to grasp the essence of a problem [ . . . ] he was singularly lacking in intellectual insight and imagination” (ibid.); “this miserable story” (p. 260); “we now should like to stress the significance of the year 1523 [the year of the publication of Luther’s Secular Authority] as the formal ending of the Middle Ages through the destruction of the symbols of Western Christian public order by the hubris of a private individual” (p. 263); “Obviously there is no way out of this mess . . . we have descended to the level of the war of all against all” (p. 265); “Luther lived for another twenty years; but with 1525 [the Peasants’ Revolt], we may say, he was finished” (p. 266); “Luther attacked and destroyed the nucleus of Christian spiritual culture through his attack on the doctrine of fides caritate formata” (p. 267); “If the splendor of the Middle Ages has become dark through the criminal ignorance and obscurantism of the modems, the influence of Luther must always be counted as one of the major causes” (ibid.); “Luther destroyed the balance of human existence” (p. 268).

These are, to say the least, strong words, even for Voegelin. And as David Morse and William Thompson point out in their helpful introduction to this volume of the History, it is nothing short of hurtful to read this for the many who still live in communities that trace their teachings back to Luther and Calvin – not least for the Lutherans, who after all still carry their founder’s name. Furthermore, Voegelin’s harsh attacks may come as something of a surprise to those who know Voegelin from his published works. While he is indeed nasty to Calvin in the New Science of Politics, in general he saves his harshest criticisms for those who immanentize history, either through the “spiritual Gnosticism” of a Joachim de Fiore, or through the secular activism of a Marx. (Indeed, being such an “immanentist” is basically the charge raised against Calvin in the New Science).3 Most readers would be relatively unaware of Luther being a major point of attack in that scheme – yet, when we read Voegelin’s remarks in the History, we find Luther appearing not only as an unbalanced thinker, but as one of the major villains of world history.

We will now try to summarize Voegelin’s main points of attack, followed by an overview of central aspects of Luther’s teaching that Voegelin seems to downplay or ignore. On that basis, we can try to answer the question whether Voegelin was fair to the famous reformer. Before doing so, however, we need to make the following important points:

The History was never revised by Voegelin for publication. Had he decided to do so, he may also have changed some of the tone of the work. Secondly, Luther is not the only author singled out for critical remarks in the History – it is more correct to say that most thinkers, especially of the modem era, receive harsh treatment at the hands of Voegelin. Finally, Voegelin wrote his the History partly as an attempt to explain the extreme horrors of his own age. Whenever he found authors who in his eyes had contributed to the totalitarian mess of the mid-201 century, he saw it as something of a duty to point out where, why, and how things had gone wrong. The treatment of Luther is, in other words, part of a complicated picture. Therefore, singling out these 70-odd pages of one volume of Voegelin’s History, without putting them into a larger context, will surely leave us with a very unnuanced and skewed image of Eric Voegelin’s monumental intellectual legacy.

Voegelin’s Points of Attack

In summarizing Voegelin’s attack on Luther – and an attack it is, indeed! – it must be remembered that Voegelin is not out to debate or criticize Luther’s theology. He comes to Luther within the frame of a history of political ideas. Thus, he concentrates on the possible dangers of Luther’s teachings in the realm of political affairs. However, Voegelin strongly believes that theological speculation can have political consequences, and – as always in Voegelin – it is hard to separate the political from the metaphysical, since the political will always be a manifestation of metaphysical conceptions of order and history, positively or negatively.

There is an interesting two-sidedness to Voegelin’s treatment of Luther. On the one hand, there is a strong indictment of Luther’s personality (a point we will come back to below). Luther himself, as a man, as a character on the public scene, is the problem. He represents disorder and lack of clarity. But on the other hand, Voegelin does not primarily – at least politically speaking – attack Luther’s own stands and actions, but more their consequences, i.e., the dangers that flow from them. He fears that Luther opens up the spectacle of unchecked individualism, lack of attention to moral virtue, and political chaos, yet he is careful to point out that Luther himself never wanted any of these things. These two facts – personality and personal stands on the one hand and political consequences on the other – are, however, closely intertwined for Voegelin. One of Luther’s main failings is exactly his lack of sensitivity to the problems he helped create. If we are, against this general background, to summarize Voegelin’s attack on Luther, we must at least point out the following:4

According to Voegelin, the famous sola fide (“faith alone”) doctrine is destructive not only of the idea that man may be justified by his works – which Voegelin sees as being pretty much a “strawman doctrine”, since few, if any, of the major theologians of the Church had ever held it in its pure form – but also of the scholastic teaching of the fides caritate formata (“faith formed by love”): the faith that touches and changes the individual, and which is part of the tension-filled process of loving God in the metaxy (in-between). The scholastic teaching had seen faith as a transformation which forms human beings and helps them love their fellows; thus theology and ethics become intertwined. For Luther, however, in his teaching of faith, there is no ethics left, according to Voegelin (p. 259): The whole realm. of problems that is to be found in the Ethics of Aristotle (der schalkichte Heide) or in the quaestiones on law in the Summa of St. Thomas does not exist for Luther. Here, and also in the discussion of Luther’s position towards the peasants in 1525 (p. 266), we see Voegelin worrying that a true ethics is the victim of Luther’s doctrine. Justification becomes merely external and leaves the sinner untouched. No “loving formation” takes place. Thus, where Augustine believed that justification through faith transforms the sinner – “becomes part of his or her person”, as Alister McGrath puts it5 – Luther holds justification to be God’s external action.

Secondly, Voegelin attacks Luther for his “antiphilosophism”, which historically speaking contributes to tearing down the high achievements of Western civilization (p. 267). Voegelin sees Luther, albeit not alone, as laying a pattern of human self-reliance and anti-intellectualism that informs the Enlightenment and subsequent developments in European thought. Clearly, Voegelin is here – as so often – tying to find the roots of that disorder which permeated his own time. (Let us remember that these passages on Luther were written in the 1940’s.) He sees somehow a genealogy of ideas stretching – backwards in time – from modem fascism, communism, and secularized liberalism, via Comte, Hegel, Voltaire, and other villains, to Luther.

The following quote is typical: [Luther’s] antiphilosophism, like Erasmus’s, has become prototypical; it has created the pattern that we find aggravated in the obscurantism of the Enlightenment philosophers, and that has reached its last baseness in the aggressive ignorance of our contemporary liberal, fascist, and Marxist intellectuals (pp. 267-268). It is tempting here to comment on Voegelin’s simplification in treating liberalism to such a significant degree as one with fascism and Marxism, but we will resist that temptation. Voegelin’s main point should be clear: Luther contributed to a revolt against learning and authority, thereby destroying that sense of tradition which balances human consciousness. It is especially the tradition from Aristotle – der schalkichte Heide (that rascally heathen, see p. 259) – which suffers at the hands of Luther; yet, the strong insistence on the authority of the individual tears down tradition and authority altogether, not only Aristotle. Voegelin realizes that this was not Luther’s stated intention, yet Luther must be blamed for instigating a movement that with necessity led to such a total revolt.

Closely related to this is Voegelin’s third main point of attack, building on Max Weber’s emphasis on the Protestant ethic: “Luther destroyed the balance of human existence” (p. 268) by shifting the emphasis from the vita contemplativa to fulfillment through work and service. Voegelin is harsh in his judgment: Today we experience the deadly results of this shift of accent; the atrophy of intellectual and spiritual culture has left a civilization that excels in utilitarian pragmatism in a state of paralysis under the threat of the modem chiliastic mass movement (ibid.).

Fourthly, and finally, Luther’s own personality, so significant for his revolution,6 comes under attack. While Voegelin includes an almost overwhelming, indeed funny – and, given his scathing criticisms, surprising – list of positive characteristics in Luther (pp. 247-249), it is nonetheless clear that Luther’s strong personality is more of an ethical liability than a moral strength. The reformer creates an atmosphere of revolt, and is portrayed by Voegelin somewhat as an elephant roaming through a porcelain store .7 No matter how sincere and well-meant the intentions of the elephant, his mere physical (and, in Luther’s case, mental) strength is and must be destructive.

In conclusion, Voegelin describes Luther and his impact as a catastrophe in Western intellectual and social history. Given the comparison with Marx (p. 245), quoted above, and his violent attack on Luther’s blindness and insensitivity to consequences, one is reminded of Voegelin’s indictment of Marx as “an intellectual swindler”.8 It is indeed something of the same image that is given of Luther; someone who should have known better, but who did not. Luther’s only defense must be his “almost incredible lack of wisdom” (p. 247). No noble defense, indeed!

In Defense of Luther

Luther was such a prolific writer that it is way beyond the task and scope of this article to give a thorough summary of his thought, even if we – like Voegelin – concentrate merely on the politically relevant. However, we will try to point out some traits in Luther that we believe could have helped ameliorate Voegelin’s harsh attacks in the History, had they been given more attention.

(a) Sola Fide – Faith Alone

First, it is important to grasp the full – or maybe we should rather say, the limited intent of the sola fide doctrine . It constitutes the third of Luther’s basic principles; the first two being sola gratia (salvation (only) through unmerited grace) and sola Scriptura (Scripture alone). Its importance pertains to justification: cum sola fidet iustificet. Face to face with God, it is faith, a gift from God, that counts.9 It is meant as an attack on what Luther found to be the wrongful, almost Pelagian, belief in man’s ability to commit actions meriting salvation or ameliorating divine judgment. Put in the language of Voegelin, Luther understands man to belong rightfully in a metaxy – an in-between – between the unchangeable and eternal God on the one hand and the ever-fleeting created world, with all its current temptations and evils, on the other. Luther’s program is to make man understand his proper place within that tension – to rediscover the metaxy, so to speak – in the face of ideas and movements which have disturbed the equilibrium, as Luther sees it, and have made man fearsome and indeed terrified in facing God and His judgment.

It is, thus, significant to remember that Luther’s teaching on faith is almost exclusively directed toward the problem of salvation and justification before God. It is one and only one question that is being answered by aid of the sola fide doctrine: “How am I to be saved?” And this is where Aristotelian scholasticism falls so radically short. Within other spheres, Luther is much less hesitant in calling on reason or appealing to heathen authorities. As Duncan Forrester has pointed out: [t]he very Aristotle whom Luther had labeled “this damned, conceited, rascally heathen” when considering his influence on theology [cf. Address to the Christian Nobility of the German Nation], becomes a most respectable authority when the question at issue is one of politics.10

The same point can be applied to one of Luther’s most famous works, De servo arbitrio, which seemingly attacks the notion of free choice per se, but which is essentially concerned with free choice as it pertains to salvation.11 Even the turn away from the fides caritate formata must be seen in this light, as Bernhard Lohse points out:

“We need to realize, however, that this scholastic distinction [between fides informis (unformed faith) and fides caritate formata (faith formed by love)] had once been drawn in order by means of Aristotelian philosophy to express the causative effect of grace respecting the believer’s renewal, while Luther had in mind the situation at the last judgment.”12

While Lohse may be over-emphasizing the Aristotelian motivation of the scholastics, he is surely right in pointing out that Luther was concerned primarily with the doctrine of faith in relation to the final judgment. Luther follows Augustine in stressing that human beings are utterly incapable of the kind of love and meritorious works that count as good in the eyes of God. This does not mean that good works and ethical behavior are impossible, merely that they do not bring us closer to salvation.13

In light of Luther’s famous Cathecisms, as well as his Biblical commentaries (e.g., his Commentary on the Galatians), it is quite clear that Luther is indeed an ethicist who strongly emphasizes not least the meaning and consequences of the Ten Commandments. The fact that man is saved by faith alone does not imply that ethics disappears or that the tradition of Christian ethics becomes unimportant to Luther. In other words, one must distinguish between Luther’s teaching on salvation through faith alone, and his ethics. His point is that ethics, no matter how good, does not lead to any ultimate perfection or salvation; he does not say that ethics is superfluous or of no consequence to the Christian.

It is almost remarkable that Voegelin, for all his clarity of vision, does not consider this point more fully. In the section immediately preceding the chapter on Luther and Calvin, Voegelin describes the so-called perfectus of Dante’s Convivio, and points out how Dante evokes an ideal of a realization of the imago Dei in mundane existence (p. 2 10). Voegelin emphasizes that Dante in this context is not concerned with salvation and the transcendental destiny of the soul (although he may be so elsewhere). Luther’s concern can be described as being diametrically opposed to Dante’s, and it thus constitutes a fine juxtaposition to the latter. The mundane sphere of existence is exactly the one we should not pin our hopes on. Together with the tradition from Augustine, we should come to see our limitations in all their starkness.

In short, debating Luther right after his treatment of Dante’s (and others’) ideals of inner-worldly fulfillment, Voegelin could have been expected to bring out the contrast to Luther more clearly. That could also have made it easier to appraise Luther’s ethics more positively, and it would have made it easier to read Luther’s doctrine on good works in a different light. As it stands, Voegelin believes that ethics, including the whole teaching of virtue and of a law of nature available to all human beings, disappears. But, as readers of Luther will know, that is not the case. The law of nature is still invoked, and Luther holds on to the need for reason in order to appraise actions in this world. But, in the face of salvation and God’s eternal punishment, none of these works deserve the name of “good”. Augustine had in effect said much the same thing.14

(b) Luther and the Augustinian Heritage

This brings us to another important point that Voegelin may be under-emphasizing. It is a fact that Luther was – in priestly practice as well as theological fact – a disciple of St. Augustine, and that he indeed understood himself as returning to the wisdom of the bishop of Hippo. Luther’s attacks on works-righteousness and on die Schwarmerei (meaning primarily the extremism) of the radical Reformation are the results of a truly Augustinian brand of deep-seated skepticism toward radical and millenarian political action in this world. This constitutes part of the core of Luther’s religious and political beliefs. While he was a radical in both speech and deed, he never wished to create an earthly paradise of the elect. (Calvin may, on one interpretation, have come closer to such an idea.) He did not believe that the political sphere could be ruled by the Gospel; the “priesthood of all believers” did not take away the need for a well-educated clergy and sound institutional authority; and, significantly, Luther created or supported no utopian political schemes – the radical action he demanded did not aim to create new institutions or rebellious factions, although they aimed to reform the state of Christendom quite radically and thoroughly.

In all this, not least in his view of the necessity of temporal authority, Luther was decisively influenced by Augustine. That Voegelin does not emphasize this deep Augustinianism that runs through Luther’s works, constitutes a weakness in his account – especially since Voegelin in general puts so much emphasis, implicitly if not always explicitly, on the Augustinian legacy in Western thought. While Luther indeed departed from Augustine on important points – for instance, in seeing grace as external and not so much as a transforming process (cf. the fides caritate formata), and in changing the highest priority among the theological virtues from love to faith – he did take Augustine’s teaching on sin and human limitations seriously, in all its radicality, and he did maintain a strong skepticism towards millennial political expectations.15 We may say that by devoting most of his attention to Luther’s relatively early Address to the Christian Nobility of the German Nation (1520), Voegelin comes to treat the most radical version of the “priesthood of all believers” as the prototype of Lutheran politics, and downplays the more subdued, Augustinian strain running through Luther.

It is not as if Voegelin is not aware of Luther’s rejection of radical sectarianism. He goes so far as to portray Luther as the first major instance of a political thinker who wants to create a new social order through the partial destruction of the existing civilizational order and then is appalled when more radical men carry the work of destruction far beyond the limits that he had set himself (p. 23 8). Voegelin, in short, charges Luther with being someone who wants to solve “complicated social and intellectual problems through limited destruction” (p. 239), but who should have known that the destructive forces thereby unleashed can hardly be held back.

The question is whether even the qualifications “partial” and “limited” make this a good and fitting description of Luther’s aim. It is quite clear from Luther’s 95 Theses and other early works of the Reformation that he was out to debate and criticize what he saw as the Church’s teaching about faith and works, aggravated by the practice of indulgences. But he did not see an institutional upheaval as called for, although he surely wished to change local dependence on the papacy (but he was far from the first Christian thinker to want that!). It is a historical fact that the Church met and answered him poorly, if at all (which is a point we will come back to).

The lack of proper replies and decent discussion about the actual matters at hand in the earliest years of the Reformation, led to impatience and fervent reactions in many circles – indeed also in Luther himself. But however radical these reactions were, to see his reform program as “destruction” (pp. 238-239), as a call to “civilizational upheaval” (p. 245), and as a seminal, almost unequaled, piece of “political mischief’ (ibid.) must be taking Luther too far, since Luther’s stated intention was to bring the Church “back” and “out”; back to its Augustinian teaching on faith, and out to a people which had been misled by an uneducated clergy and a partly corrupt Church bureaucracy.

Voegelin does admit this restraint in Luther when he speaks of the Lutheran and Calvinistic idea of a terrestrial paradise as, after all, a “respectable eschatology” (p. 259),16 in contradistinction to other more chiliastic and revolutionary ideas. But here it seems to us that Voegelin lumps together Luther and Calvin too easily. It cannot be inferred from Luther’s writings that he believed in any ideal, Christian terrestrial society whatsoever. He was too deeply imbued with Augustinian skepticism towards mundane existence to immerse himself in such utopian dreaming. )while Calvin had more of a philosophical foundation than Luther, and drew more explicitly on especially Stoic and to a certain extent Aristotelian notions of politics and law, Luther is closer to the Augustinian fear of “political theology”, and thus actually more open than Calvin to a “non-scriptural” politics, which in turn allows for more versatility and openness than Calvin’s ultimately dreary Geneva ever could.

(c) “The Affirmation of Ordinary Life”

A further, connected point that deserves attention is Voegelin’s discussion of Luther’s this-worldly ethics, which we also touched on above. Whereas Voegelin sees Luther’s teaching as implying a “lack of ethics”, instead creating a new and anti-authoritarian individualism that tears down the fine medieval balance between the individual and authority, it is possible to see Luther’s turn toward the spirituality and conscience of the common man in another and more favorable ethical light.

Our point may be explained in the following way: Voegelin draws a historical line from the Protestant Reformation to a German pietism with “the propensity to insulate an existence understood as Christian from the profane, impure sphere of the political” – in contrast to the Anglo-Saxon development, deeply influenced by the “Second Reformation” of John Wesley, which “carried Christendom . . . to the people . . . and thereby virtually immunized them against later ideological movements”.17 According to Voegelin, the German development, with roots in the 161-century Reformation, had torn politics and Christianity apart, leaving no spiritual resources to combat extremism and, in the 20d, century, totalitarianism.

While such an image has considerable historical plausibility, it is important to ask whether and to what extent Luther is to blame. Luther could, after all, be said to be responsible for a very different trend in the Western history of ideas, namely, that which Charles Taylor has called “the affirmation of ordinary life”;18 in one sense the very antithesis to that extreme pietism that some of Luther’s followers came to espouse, and that Voegelin indicts for creating fertile ground for nihilistic and totalitarian movements (by creating a radical separation between the religious and the mundane spheres of life, thus allowing for no true dialogue between the two).19 After all, we find the Wittenberg reformer being as abhorred as Voegelin by that ignorance of the masses which so easily leads to uncritical acceptance of ideological dogma.

Simultaneously, and also quite parallel to Voegelin, Luther expresses fear of an elitism that denies true spirituality and dignity to everyday people in ordinary life. The life of a shoemaker or an innkeeper, married life with children, everyday life with its worries and joys – these have as much grace and nobility as the life of reflection or political grandeur, according to Luther. This does not mean that reflection is unimportant, or that political life is without dignity, which is the unwarranted conclusion that may be drawn from Luther’s often fiery remarks. His point is that these forms of life may all be combined. Spiritual or political life is not out of reach for the common man.20

Thus, Luther undoubtedly helps lay the foundation of the modem idea of mass education and democratic self-government, not least through his Bible translations and his Cathecisms. Luther can be accused of being both naive and inconsistent in his ambitions, but his aim is at least not “chiliastic” or “millenarian”; rather he can be seen as following up on the Augustinian teaching about the limited, but important tasks of government in this world, and the inevitable limitations and shortcomings of all schemes intended to create an inimanentized sort of “gospel perfection”, available only to the “Gnostic” elite. This could possibly have been brought out more explicitly by Voegelin, creating the basis for a more nuanced picture of the reformer.

(d) Luther’s Problematic Personality – and the Church’s Reply

This brings us to a final point not without relevance for Voegelin’s discussion; namely, Luther’s personality.21 Clearly, Voegelin is right in singling out Luther as a problematic personality whose bold writings and sayings could be – and indeed were – taken out of context and used as pretexts for extreme and radical action. He lacked a balance, an acute sense of moderation in speech (and, to a certain extent, deed), which we expect of great thinkers and heroic political and religious actors. Yet, as Voegelin himself so ably points out, Luther had a keen eye for those ills that needed immediate correction.

His were “the talents that one should like to see in an influential cabinet member of a democratic welfare state” (p. 248), as Voegelin amusingly puts it. We would like to claim that it is plausible – if only partially true – that Luther’s proposals and reactions, theologically and politically, were indeed quite healthy and called-for, and that it was the reply that was sadly lacking. A stronger Church institution would have managed to contain the shock of a Martin Luther, and even exploit the shock to a useful purpose. Luther’s call to a reform of Christendom could have been contained had the Church itself shown willingness to reform. Undoubtedly, many spiritual and religious people were willing to listen to and support the calls to change. But the papal institution and many of those dependent on it for their living did not show the same kind of willingness to engage in serious debate and unselfish soul-searching.22

When Voegelin, in a striking and funny sentence, holds that “if anything is characteristic of the Reformation, it is that nobody could keep quiet, or could be kept quiet” (p. 230), one lamentfully thinks of the fact that the Roman Church initially did keep too quiet, that its replies to Luther’s challenges were woefully lacking, and that this contributed to a situation that got out of hand and ended in a century of bloodshed the European continent did not see the like of until the 20″ century. If nothing else, the blame for the tragedies that followed in the wake of the Reformation must be shared, a conclusion Voegelin would certainly not have disagreed with (to judge from the general treatment of this period in Voegelin’s History), but which – we suggest – could have been emphasized more clearly in the chapter on Luther and Calvin.

Conclusion

Any reader who finds Voegelin’s treatment of Luther too harsh, should just look at those polemical tracts that were written in Luther’s own day. Luther was attacked from the left and right, and all kinds of slander were heaped on him. The radical reformer Thomas Muntzer customarily referred to him as Doctor Liar (Doctor Lugner; a word-play on Doctor Luther),23 and a balanced thinker such a Francisco de Vitoria referred to Luther as “the most imprudent of all”,24 and said that he had “left no nook untainted with his heresies”.” Closer to our own time, a moderate Catholic thinker such as Jacques Maritain said tersely that Luther was “not intelligent, but limited – stubborn especially”, and totally marked by “egocentrism … a metaphysical egoism”.26 Much has happened over the previous half-century, however. Catholic writers have come to treat Luther much more sympathetically,27 and official documents and declarations, most recently in 1999, have managed to reconcile Catholics and Lutheran Protestants to an unprecedented degree.

There is little doubt that Voegelin would have rejoiced at such progress, to the extent he saw it as engaging the two sides in the real questions and not quasi-problems. These remarks notwithstanding, Voegelin’s discussion of Luther in the History is indeed brutal. And Luther understood, of course, that such would be the attacks on him. After all, and without any doubt, Luther is himself one of the most polemical and fiery writers of Western history, much like Eric Voegelin himself. In style, if not in substance, they are probably more similar than Voegelin would have cared to admit.

References

Bainton, Roland H. (1950). Here I Stand: A Life of Martin Luther. Nashville: Abingdon Press.

Baylor, Michael G., ed. (199 1). The Radical Reformation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Bokenkotter, Thomas (1990). A Concise History of the Catholic Church, rev. & expanded ed. New York: Image Books.

Forrester, Duncan (1987). “Martin Luther and John Calvin”, in History of Political Philosophy, 3rd ed., eds. Leo Strauss & Joseph Cropsey. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Lohse, Bernhard ([1995]1999). Martin Luther’s Theology, trans. & ed. Roy A. Harrisville. Edinburgh: T & T Clark.

Luther, Martin (1961). Selections from His Writings, ed. John Dillenberger. New York: Doubleday.

Maritain, Jacques (1929). Three Reformers: Luther, Descartes, Rousseau. New York: Thomas Y. Crowell.

McGrath, Alister (1994). Christian Theology: An Introduction. Cambridge, MA Oxford: Blackwell.

McNeill, John T. (1946). “Natural Law in the Teaching of the Reformers”, Journal of Religion, vol. XXVI, no. 3, pp. 162-182.

Oakley, Francis (1991). “Christian Obedience and Authority, 1520-1550”, in The Cambridge History of Political Thought, 1450-1700, ed. J. H. Bums. Cambridge:Cambridge University Press.

Oberman, Heiko [1982]1992). Luther: Man between God and Devil, trans. Eileen Walliser-Schwarzbart. New York: Image Books.

Pelikan, Jaroslav (1984). Reformation of Church and Dogma. (Vol. 4 of The Christian Tradition: A History of the Development of Doctrine.) Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Taylor, Charles (1989). Sources of the Self. Cambridge: Cambridge University Pres.

Villa-Vicencio, Charles (1986). Between Christ and Caesar. Cape Town: David Philip.

Vitoria, Francisco de (199 1). Political Writings, eds. Andiony Pagden & Jeremy Lawrance. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Voegelin, Eric (1952). New Science of Politics. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

– (1968). Science, Politics, and Gnosticism. Washington, DC: Regnery Gateway.

– (I 998a). History of Political Ideas, vol. IV. Renaissance and Reformation, eds. David L. Morse & William A Thompson. (Vol. 22 of The Collected Works of Eric Voegelin, series ed. Ellis Sandoz). Columbia: University of Missouri Press.

– (1 998b). History of Political Ideas, vol. V. Religion and the Rise of Modernity, ed. James L. Wiser. (Vol. 23 of The Collected Works of Eric Voegelin, series ed. Ellis Sandoz). Columbia: University of Missouri Press.

– (2000). Published Essays 1953-1965, ed. Ellis Sandoz. (Vol. I I of The Collected Works of Eric Voegelin, series ed. Ellis Sandoz). Columbia: University of Missouri Press.

Notes

1 The authors would like to thank Ellis Sandoz for helpful comments.

2 The exact title of the chapter is “The Great Confusion 1: Luther and Calvin”. The next chapter, “The Great Confusion 11: Decisions and Positions”, in Voegelin 1998b, pp. 17-69, details the results of the Reformation by analyzing the political thought of the 161 century. Voegelin’s judgment is characteristically harsh: “. . . the sixteenth century is singularly barren with regard to work of intellectual distinction in politics – if we except Bodin Nothing else can be expected, considering that the antiphilosophism of the reformers had discredited the scholastic medium in which political thought could be articulated (ibid., p. 17).

3 About Calvin in the New Science of Politics, Voegelin writes: “… a man who can break with the intellectual tradition of mankind because he lives in the faith that a new truth and a new world begin with him, must be in a peculiar pneumopathological state” (Voegelin 1952, p. 139).

4 See also the editors’ introduction, p. 13, for a summary of the same points.

5 McGrath 1994, p. 441.

6 See the editors’ introduction, p. 13.

7 Our image, not Voegelin’s!

8 Voegelin 1968, p. 28.

9 See Oberman [ 1982]1992, p. 192.

10 Forrester 1987, p. 331. See also Oakley 1991, pp. 170-171, on the importance and use of natural-law arguments and appeals to reason in Luther’s political theology, with reference especially to Whether Soldiers, too, Can be Saved and Temporal Authority: To “at Extent it Should be Obeyed.

11 See Lohse [1995]1999, pp. 160-168, for a good summary.

12 Ibid., p. 202.

13 For more on Luther’s teaching on “good works”, see his Treatise on Good Works, usefully commented on in Pelikan 1984, p. 147. See also Bainton 1950, pp. 178-179, and Bainton’s comments on Luther’s On the Freedom of the Christian, a work in which the effects of faith on good works are detailed. The strong connection between faith and the quality of works challenges the common claim that Luther totally rejected the fides caritateformata. Something actually happens, positively, to the person who comes to faith in Christ.

14 See McNeill 1946 for a fine and thorough, albeit debated, overview of the many references to natural-law ethics in Luther and other reformers. See also Oakley 1991.

15 For a useful summary of the debate about Luther’s Augustinianism, see Pelikan 1984, pp. 251-253.

16 The expression is repeated in Voegelin 1998b, p. 20.

17 The quotes are from a lecture on “Freedom and Responsibility in Economy and Democracy” (1960), reprinted in Voegelin 2000, pp. 70-82; for these quotes, see p. 72.

18 Taylor 1989, pp. 211 ff.

19 As Taylor points out pietism and puritanism – in themselves broad concepts which encompass many thinkers and groups – were indeed part of the movement that criticized medieval monasticism and spiritual elitism; thus they are part and parcel of the modem movement toward the “affirmation of ordinary life”. However, Luther’s variant is much more down-to-earth and less ascetic than what we often associate with pietism and puritanism.

20 Possibly the clearest exposition of this point in Lutheran teaching can be found in the Augsburg Confession, art. 16; see Villa-Vicencio 1986, p. 47. In both Cathecisna the same emphasis is evident in connection with Luther’s comments and explanations of the Commandments.

21 See John Dillenberger, in Luther 1961, p. xiii, for a brief but useful discussion of the relationship between Luther’s personality and the many attacks on him.

22 See Bokenkotter 1990, p. 193; see also Lohse [1995]1999, pp. 110-117, for a summary and discussion of the unsuccessful encounter with Cajetan in 1518, and the following contact between Luther and Rome, reinforcing the impression of a failure of communication and true dialogue.

23 See Muntzer, A Highly Provoked Defense, in Baylor 199 1, pp. 74-94.

24 Vitoria, On the Power of the Church, qu. 2, art. 1; in Vitoria 199 1, p. 126. 21

25 Vitoria, On the Law of War, qu. 1, art. 1; in Vitoria 1991, p. 296. 16

26 Maritain 1929, pp. 5, 14. We thank our friend Gregory Reichberg for making us aware of this interesting early work by Maritain.

27 See Bokenkotter 1990, pp. 186-200 for a balanced exposition from a Catholic viewpoint.