Flannery O’Connor’s Writing: A Guide for the Perplexed

Many readers have been fascinated with Flannery O’Connor as a person and author, perhaps for some of the same reasons I find her so engaging. I wish to mention briefly four minor but not insignificant features that attract me and then focus on three main reasons for her enduring stature among readers, teachers, and critics.

O’Connor had a very sharp eye and ear for the sights and sounds of her native land. And for me, a native of western North Carolina living in exile in the Midwest, it is a joy to encounter the “Southernness” in her fictional world, despite the fact that this world she presents is often not at all lovely. She did not wear rose-colored glasses, and her eye seized upon the depraved, the vulgar, and the grotesque. But there is no doubt that she captured the Southernness of her region. I think of the ubiquitous “Jesus Saves” and “Except ye repent, ye shall all likewise perish” messages printed on billboards, painted on barns, or scrawled on boulders. I think of the way her characters talk. Their idioms, diction, pronunciation, and grammar reveal O’Connor’s masterly use of regional dialect: “It isn’t a soul in this green world of God’s that you can trust.” “Hep that lady up, Hirum.” “Lady, there never was a body that give the undertaker a tip”—a few memorable sentences from “A Good Man Is Hard to Find.” “Ain’t there somewheres we can sit down sometime?” “I just want to know if you love me or don’tcher.” “One time I got a woman’s glass eye this way. And you needn’t to think you’ll catch me because Pointer ain’t really my name. I use a different name at every house I call at and don’t stay nowhere long. And I’ll tell you another thing, Hulga, you ain’t so smart. I been believing in nothing ever since I was born!”—from Manley Pointer’s comments to Hulga Hopewell in “Good Country People.”

I think O’Connor is as good as Mark Twain when it comes to realistically rendering both the comic and the tragic vision in a distinctively Southern idiom. About 120 years before O’Connor wrote her fiction, Georgia writer Augustus Baldwin Longstreet said he hoped his Georgia Scenes (1835) would accurately capture the scenes, manners, and speechways of his rapidly changing region. O’Connor has certainly done that for us in our time.

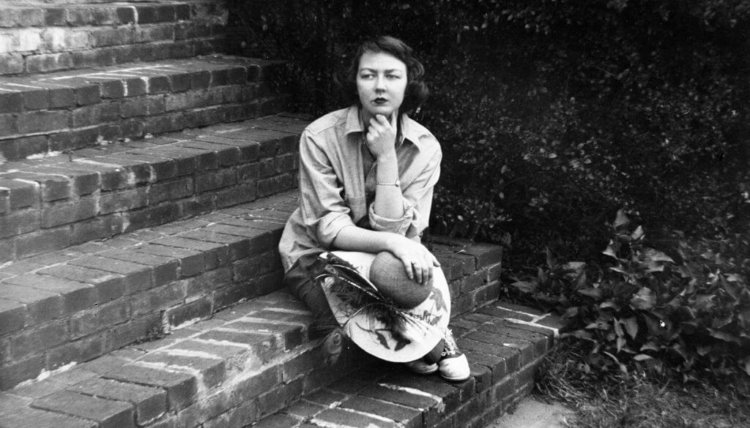

O’Connor is also attractive to me because she has a manageable body of literature. One can easily read all of her published work: her fiction (thirty-one short stories and two novels); a one-volume collection of occasional lectures and prose writings (on her own fiction and on the art of fiction in general); and two collections of her letters. Her literary output is small for two reasons: first, she was a slow writer, and a painstaking one. She worked five years on Wise Blood, at 232 pages a relatively short novel. Secondly, at the age of twenty-six she was stricken with lupus, an incurable disease that limited her writing time and energy and shortened her life. She died young—in 1964, only thirty-nine years old.

Her prose style is yet another reason she’s one of my favorite authors. When asked by students which authors I recommend as prose stylists (for in reading a good author we can pick up some of his virtues), I recommend three: Jonathan Swift, George Orwell, and Flannery O’Connor. What she writes is clear, pungent, and memorable. She can effectively say more in a few sentences than most of us can ineptly say in several pages.

I also like her and recommend her because of her very sensible advice concerning teaching literature to middle- and high-school students. This advice, found in Mystery and Manners, has been of value to me as a teacher of college students. Here are a few of her convictions that should interest all literature teachers. O’Connor believed that parents should exercise some control over the content of their children’s education. She thought that both parents’ consent and students’ preparation should determine whether high school seniors read questionable modern novels. O’Connor recommends that students should read the older writers before dipping into modern works: they should read eighteenth- and nineteenth-century British novelists before reading nineteenth-century American novelists. And they should read Hawthorne before reading Steinbeck, or her own work, for that matter. Much modern literature is more complicated as well as more scandalous than literature from earlier times, so O’Connor very sensibly recommends that students should be prepared for the modern by reading in the tradition out of which modern writing comes.1

O’Connor did not believe in student-centered education; that is to say, she did not believe teachers should ask students what they would like to read. I quote her on this point:

“The high-school English teacher will be fulfilling his responsibility if he furnishes the student a guided opportunity, through the best writing of the past, to come, in time, to an understanding of the best writing of the present. He will teach literature, not social studies or little lessons in democracy or the customs of many lands.

And if the student finds that this is not to his taste? Well, that is regrettable. Most regrettable. His taste should not be consulted; it is being formed.”2

One final note from O’Connor concerning the teaching of literature. She claims that the literature teacher’s business should be to “change the face of the best-seller list” and that “There’s many a best-seller that could have been prevented by a good teacher.”3While I don’t read the best-sellers, I’ve read enough reviews of them to convince me that most contemporary readers do not have very discriminating taste when it comes to modern or older fiction. So all literature teachers have a good work to do: educate students so that they will be able to recognize both rot and excellence in writing. In time this discriminating teaching might “change the face of the best-seller list.”

The accurate dialect and realism in her “Georgia Scenes,” her prose style, the manageable body of writings, and her sensible advice regarding the teaching of literature—these are some of the reasons I am attracted to O’Connor as a person and author. And I believe these and other reasons may have something to do with her continuing presence among us as a noteworthy author. For about forty years her work has been the object of lively popular and critical interest, and all of that work is still in print: her two novels (Wise Blood [1952] and The Violent Bear it Away [1960]); all three collections of her short stories: (A Good Man Is Hard to Find [1955], Everything That Rises Must Converge [1965], and The Complete Stories [1971]); a selection of her essays and lectures (Mystery and Manners [1961]), and two collections of her letters, the most important one titled The Habit of Being [1980].4Thousands of periodical essays have been written about her work, hundreds of Ph.D. dissertations, and probably well over a hundred book-length studies. The Oxford Companion to Women’s Writing in the United States notes that “O’Connor attracts the critical attention of more scholars each year than any other twentieth-century American woman writer.”5In other words, she is the female equivalent of the great Mississippi writer and her fellow Southerner William Faulkner. The Flannery O’Connor Bulletin, an annual publication devoted to the Catholic realist from Milledgeville, Georgia, has appeared every year since 1972. Some of her fiction has even made it into television and the movies, an achievement about which she no doubt had mixed feelings. At any rate, all of the publishing activity and the movies indicate something of the fascinated response many readers have to her fiction.

I think there are at least three main reasons for the continuing fascination with O’Connor. First, readers are intrigued by the sense of humor and the hard yet radiant wit evident in nearly all of her productions; second, they are attracted by the Christian vision illuminated in her essays, letters, and incarnational art; and third, they are astonished by her gifts as storyteller, gifts which are evident in the depth of her especially unsentimental realism, in her eye for the absurd and the grotesque (for freaks and sinners like you and me), and in the shocking plots and violent characters in her fiction. Looking into her letters, fiction, and essays, I would like to illustrate this humor and wit, the Christian vision, and her writing technique and view of the fiction-writer’s art.

Epistolary Humor and Wit

Let us begin with the humor and wit evident in her letters. Actually, the letters reveal the humor and wit, the Christian vision, and some of her views of the writer’s art. This suggests something of her integrity as a private person and a public author.

Her letters are astonishing when one considers O’Connor’s circumstances when most of them were written: in 1951, at the age of twenty-six, she was afflicted with lupus erythematosus, a painful, debilitating, incurable disease which had killed her father and slowly killed her. She occasionally mentions her sickness in her letters, but there is no sentimentality, no self-pity. When she does mention herself or her sickness in these letters, she reveals a good deal of sardonic humor and comic self-deprecation. But let us sample the comedy, the sparkling wit, and the witty judgments in some of these letters.

In a letter to Brainard Cheney, O’Connor explains that she and her mother, Regina, attend the 7:15 mass. Why? “I like to go to early mass so I won’t have to dress up—combining the 7th Deadly Sin with the Sunday obligation.” Concerning some photographs which Mrs. Cheney had sent to her, O’Connor self-deprecatingly observes: “That decidedly ain’t me except in the picture which looks like an ad for acid indigestion. People in Nashville will wonder what you fed me.” When plans were being made for a pilgrimage to Rome, O’Connor wrote to the Cheneys:

“My mother is all for it. I am not so sure I can stand it—seventeen days of Holy Exhaustion—but I suppose this is the only way I’ll ever get there. My mother and me facing Europe will be just like Mr. Head and Nelson facing Atlanta. [Mr. Head and Nelson are characters in her story ‘The Artificial Nigger.’] Culture don’t effect me none and my religion is better served at home; but I see plenty of comic possibilities in this trip.”6

Writing to Sally and Robert Fitzgerald, O’Connor indicated what she might do with money she received from a Kenyon Fellowship: she thought of broadening her perspective:

“into the ways of the vulgar. I would like to go to California for about two minutes to further these researches, though at times I feel that a feeling for the vulgar is my natural talent and don’t need any particular encouragement. Did you see the picture of Roy Rogers’s horse attending a church service in Pasadena? I forgot whether his name was Tex or Trigger but he was dressed fit to kill and looked like he was having a good time. He doubled the usual attendance.”7

As it turned out, O’Connor never went to California. She knew that she did not have to go to California, New York City or any other place to find vulgarity, freaks, or sinners. She knew that poor taste, not to mention modern and ancient vices, easily took root in Southern hearts and minds.

In a late letter to Sally Fitzgerald, written in 1964 “after her return from the hospital and surgery,” she wrote:

“One of my nurses was a dead ringer for Mrs. Turpin [the protagonist in O’Connor’s “Revelation”]. Her Claud was named Otis. She told all the time about what a good nurse she was. Her favorite grammatical construction was “it were.” She said she treated everybody alike whether it were a person with money or a black nigger. She told me all about the low life in Wilkinson County. I seldom know in any given circumstances whether the Lord is giving me a reward or a punishment. She didn’t know she was funny and it was agony to laugh and I reckon she increased my pain about 100%.”8

Much of O’Connor’s humor, in her stories as well as in her letters, has a point to it. It makes us wince even while we laugh. Here are a few examples from her letters. After reviewing a book of rather sentimental short stories from the American Catholic Press for The Bulletin, O’Connor wrote the Cheneys: “I have decided the motto for fiction in the Catholic press should be: ‘We guarantee to corrupt nothing but your taste.’” In another letter, she related to the Cheneys her lecture comments to a group of ladies at a Catholic Parish Council: “I did tell them that the average Catholic reader was a Militant Moron. They sat there like a band of genteel desperadoes and never moved a face muscle. I might have been saying the rosary to them.”9

O’Connor did not think much of the learning and acumen of the Protestant groups to whom she lectured, either. She observed to the Cheneys: “At all the Methodist and Baptist institutions that I normally talk at around here, I quote St. Thomas prodigiously and as the audience is never too sure who he is, it is always much impressed.”10O’Connor’s opinion of the average reader, Catholic or otherwise, was not high, nor was she pleased with what “the devil of Educationism” (her phrase in Mystery and Manners)11was accomplishing in American schools and colleges, religious or secular.

Christian Vision and Literary Technique

In discussing O’Connor’s Christian vision it is best to include a discussion of her literary techniques, for the two are clearly connected. On many occasions O’Connor commented on the relationship between her Christian vision and her literary art. She did so because her readers (initially myself included) either did not detect a Christian vision in her work or misunderstood it. When I first read “A Good Man Is Hard to Find,” I found it disturbing, not at all comic. The only spiritual purpose I detected was negative: the Misfit’s nihilism easily overpowering the Grand-mother’s shallow, sentimental Christianity. But after reading more of O’Connor’s fiction, her own writings on the subject, and what a few critics had written, I began to see the rich comedy in her stories and the spiritual vision which makes the comedy possible and puts it in perspective. If read in the right spirit and with spiritual perception, her stories are terribly funny and spiritually vivid. It is terribly funny when the Misfit tells Bobby Lee and Hirum, “She would of been a good woman if it had been somebody there to shoot her every minute of her life.”12The Misfit’s comment reveals spiritual purpose as well: threatened with a violent death, on the brink of eternity, the Grandmother becomes a “good woman,” recognizes her kinship with the Misfit, and receives grace from heaven.

In “The Fiction Writer and His Country,” written in 1957, O’Connor discussed the Christian vision implicit in her fiction. Noting that many modern readers complained of a lack of spiritual purpose and the absence of the joy of life in modern fiction (her own fiction included), she made this declaration regarding her beliefs: “I am no disbeliever in spiritual purpose and no vague believer. I see from the standpoint of Christian orthodoxy. This means that for me the meaning of life is centered in our Redemption by Christ and what I see in the world I see in its relation to that.”13If this is true, why did so many early readers fail to see the spiritual purpose in her work?

Our secular, materialistic age has something to do with our blindness. And O’Connor’s artistic integrity plays a role as well. She is a literary artist, not a preacher or teacher of moral philosophy. She believes that fiction is art, not primarily moral instruction, not a type of catechism. Straightforward preaching, explicit prophecy, direct moral instruction—these modes of discourse belong to preachers, priests, and moralists. The fiction writer’s duty is to tell a story, and any morality or prophecy or spiritual vision in the story should be conveyed dramatically, not in essay or sermon fashion.

One could say that the spiritual purpose in O’Connor’s fiction is disguised. Nevertheless, her Christian vision is manifested in her literary techniques. Brainard Cheney, an early critic who noted this manifestation in his 1964 Sewanee Review essay on her fiction, brings into perspective O’Connor’s humor, her Christian vision, and her purpose as a writer:

“In addition to being a brilliant satirist, she was a true humorist and possessed an unusual gift for the grotesque. But she resorted to something far more remarkable to reflect her Christian vision to a secular world. She invented a new form of humor. . . . This invention consists in her introducing her story with familiar surfaces in an action that seems secular, and in a secular tone of satire or humor. Before you know it, the naturalistic situation has become metaphysical and the action appropriate to it comes with a surprise, an unaccountability that is humorous, however shocking. The means is violent, but the end is Christian.”14

O’Connor herself makes the same point in “Novelist and Believer” when she discusses the significance of baptism in The Violent Bear It Away, a novel in which young Tarwater baptizes (actually drowns) his idiot cousin, Bishop:

“When I write a novel in which the central action is a baptism, I am very well aware that for a majority of my readers, baptism is a meaningless rite, and so in my novel I have to see that this baptism carries enough awe and mystery to jar the reader into some kind of emotional recognition of its significance. To this end I have to bend the whole novel—its language, its structure, its action. I have to make the reader feel, in his bones if nowhere else, that something is going on here that counts. Distortion in this case is an instrument; exaggeration has a purpose, and the whole structure of the story or novel has been made what it is because of belief. This is not the kind of distortion that destroys; it is the kind that reveals, or should reveal.”15

This same analysis can be applied to her short story “The River,” in which the boy Bevel baptizes himself. Once again the baptism is violent. He drowns, but we are led to believe that he has indeed left this life of sin, sorrow, and suffering for a glorious life in the Kingdom of Christ. To repeat Cheney’s remarks, “the naturalistic situation has become metaphysical.” The physical drowning is a spiritual birth. “The means is violent,but the end is Christian.” When reading O’Connor’s fiction, one is reminded of Saul’s violent encounter with Christ on the Road to Damascus and of John Donne’s Holy Sonnets, where violence is an instrument of grace in hard-headed and hard-hearted men.

Because we live in a secular age, O’Connor uses violence, exaggeration, distortion to shock us into a serious consideration of religious dogmas and mysteries. In “Catholic Novelists and Their Readers” she mentions three Christian doctrines most modern readers reject but which are the foundation of the Catholic writer’s universe, her own included:

“the Fall, the Redemption, and the Judgment. These are doctrines that the modern secular world does not believe in. It does not believe in sin, or in the value that suffering can have, or in eternal responsibility, and since we live in a world that since the sixteenth century has been increasingly dominated by secular thought, the Catholic writer often finds himself writing in and for a world that is unprepared and unwilling to see the meaning of life as he sees it. This means frequently that he may resort to violent literary means to get his vision across to a hostile audience, and the images and actions he creates may seem distorted and exaggerated to the Catholic mind.”16

As she put it in another context:

“The novelist with Christian concerns will find in modern life distortions which are repugnant to him, and his problem will be to make these appear as distortions to an audience which is used to seeing them as natural; and he may well be forced to take ever more violent means to get his vision across to this hostile audience. When you can assume that your audience holds the same beliefs you do, you can relax a little and use more normal means of talking to it; when you have to assume that it does not, then you have to make your vision apparent by shock—to the hard of hearing you shout, and for the almost-blind you draw large and startling figures.”17

Other passages from Mystery and Manners shed light on the spiritual purpose manifested in her fiction. She wrote: “I suppose the reasons for the use of so much violence in modern fiction will differ with each writer who uses it, but in my own stories I have found that violence is strangely capable of returning my characters to reality and preparing them to accept their moment of grace.” “In my stories a reader will find that the devil accomplishes a good deal of groundwork that seems to be necessary before grace is effective.” She writes that in her fiction, “the devil [is] the unwilling instrument of grace” and that her “subject in fiction is the action of grace in territory held largely by the devil.”18

These remarks help us to see what she once called “the lines of spiritual motion” in her stories.19In “A Good Man Is Hard to Find,” the Misfit and his two assistants casually murder the Grandmother’s family. This helps the Grandmother accept her moment of grace moments before the Misfit puts three bullets through her chest. In “Revelation,” Mary Grace (and here the name is suggestive of the role she plays in the story)—Mary Grace hurls a psychology book into Mrs. Turpin’s face and says: “Go back to hell where you came from, you old wart hog.” This rude encounter in the doctor’s office helps to prepare Mrs. Turpin for her final revelation at the pig parlor at the end of the story. Initially very self-righteous, complacent, and conceited about religious matters, initially so pleased that God had made her a respectable white lady and not white trash or what she calls a “nigger,” Mrs. Turpin receives a vision of the end of time:

“A visionary light settled in her eyes. She saw the streak as a vast swinging bridge extending upward from the earth through a field of living fire. Upon it a vast horde of souls were rumbling toward heaven. There were whole companies of white-trash, clean for the first time in their lives, and bands of black niggers in white robes, and battalions of freaks and lunatics shouting and clapping and leaping like frogs. And bringing up the end of the procession was a tribe of people whom she recognized at once as those who, like herself and [her husband] Claud, had always had a little of everything and the God-given wit to use it right. She leaned forward to observe them closer. They were marching behind the others with great dignity, accountable as they had always been for good order and common sense and respectable behavior. They alone were on key. Yet she could see by their shocked and altered faces that even their virtues were being burned away.”20

I suppose we might call this a modern version of the Parable of the Pharisee and the Publican.

In “Good Country People,” Manly Pointer is a satanic character who appears to be an angel of light—that is, he is a Bible salesman who claims to be devoted “to Christian service.” He may serve as an unwilling instrument of grace when he steals Hulga’s wooden leg, leaving her stranded in the barn. She was an armchair nihilist who did not believe in God; she claimed to see through all illusions, to “see through to nothing,” as she put it.21But after her rude encounter with Manley Pointer, we realize, and she does too, that she does believe in such basic virtues as honesty and fair dealing. Her illusion of nihilism is shattered, and she may very well leave that barn a different person than she was when she entered it.

Ashbury in “The Enduring Chill,” Mr. Shiflet in “The Life You Save May Be Your Own, ” Mr. Head in “The Artificial Nigger”—all are brought to a moment of grace or a moment of judgment by means of violence. In nearly all of these stories we do not know whether or not the protagonists accept their moment of grace, but we do sense that they have been exposed to something verging on the borderland of mystery. And if we read this fiction in the spirit in which it was written, our own sense of spiritual realities and spiritual mysteries will be enhanced.

Christian Faith, Modern Secularism, and Southern Identity

O’Connor’s Christian faith and the modern secular spirit—these two ingredients collided to produce her remarkable fiction. Her deeply grounded and acute Christian understanding of the world made her a vigorous and effective opponent of modern secularism. She traced the secular and rationalizing tendencies of modernity back to the sixteenth century, but especially to the eighteenth century, the so-called age of Enlightenment. In “Some Aspects of the Grotesque in Southern Fiction,” she remarked:

“Since the eighteenth century, the popular spirit of each succeeding age has tended more and more to the view that the ills and mysteries of life will eventually fall before the scientific advances of man, a belief that is still going strong even though this is the first generation to face total extinction because of these advances.”22

In the Age of Enlightenment intellectuals began to believe in the Progress of Society and in the Perfectibility of Man. Deliberately divorcing themselves from their past, they exchanged a religion based upon revelation and tradition for a new one based upon man’s secular reason and his ability to master nature. Attracted to abstract reason and scientific materialism, modern man becomes epistemologically narrow, limited, insular, and provincial. Strongly opposed to this sort of provincialism, O’Connor knew that it was alive and well all over the land, even in the Protestant South—what H. L. Mencken derisively called “the Bible Belt.” Rayber in The Violent Bear It Away, Sheppard in “The Lame Shall Enter First,” Hulga in “Good Country People,” Hazel Motes in Wise Blood(before his disturbing rebirth as a grotesque Christian ascetic and mystic)—these are some of the Southerners in her fiction who espouse modern secularism. But the South also has its shouting fundamentalists, its backwoods prophets such as old and young Tarwater in The Violent Bear It Away, the Reverend Bevel Summers in “The River,” and Wendell and Cory Wilkins in “The Temple of the Holy Ghost.” O’Connor pointed out that she felt “a good deal more kinship with [the South’s] backwoods prophets and shouting fundamentalists” than “with those politer elements for whom the supernatural is an embarrassment and for whom religion has become a department of sociology or culture or personality development.”23

Both the secularists and the Protestant fundamentalists in her fiction are grotesques, freaks who make some modern readers uncomfortable. O’Connor explained why in “The Teaching of Literature”: “It is only in these centuries when we are afflicted with the doctrine of the perfectibility of human nature by its own efforts that the vision of the freak in fiction is so disturbing. The freak in modern fiction is usually disturbing to us because he keeps us from forgetting that we share in his state.” O’Connor thought that Southerners were able to see and assimilate freaks more readily than people from other sections of the country:

“Whenever I’m asked why Southern writers particularly have a penchant for writing about freaks, I say it is because we are still able to recognize one. To be able to recognize a freak you have to have some conception of the whole man, and in the South the general conception of man is still, in the main, theological. . . . I think it is safe to say that while the South is hardly Christ-centered, it is most certainly Christ-haunted. The Southerner, who isn’t convinced of it, is very much afraid that he may have been formed in the image and likeness of God.”

If we readily recognize the freak, who might be a prophet, a nihilist, or a secular humanist, we will sense him “as a figure for our essential displacement.”24

O’Connor once described a collection of her short fiction as “nine stories about original sin.” She reminds us that we are all children of Adam, not of that ideal man imagined by Voltaire and other thinkers from the Age of Enlightenment. Because the Enlightenment has had a slower dawning in the South, many Southerners still claim their patrimony. Writing to Cecil Dawkins, O’Connor juxtaposed the Southern vision of man in society with that of the enlightened or modern liberal:

“The notion of the perfectibility of man came about at the time of the Enlightenment in the 18th century. This is what the South has traditionally opposed. . . . The South . . . still believes that man has fallen and that he is perfectible by God’s grace, not by his own unaided efforts. The Liberal approach is that man has never fallen, never incurred guilt, and is ultimately perfectible by his own efforts. Therefore, evil in this light is a problem of better housing, sanitation, health, etc. and all the mysteries will eventually be cleared up.”25

O’Connor wholeheartedly rejected this liberal or Enlightenment version of human nature and this faith in secular reason and applied science. Like most of us, she appreciated many of the creature comforts and advances in medicine, but she was not willing to measure the health of the country by a materialistic yardstick. She even said that the writer interested in spiritual concerns would likely “take the darkest view of all of what he sees in this country today. For him, the fact that we are the most powerful and wealthiest nation in the world doesn’t mean a thing in a positive sense.”26

Our nation’s power and prosperity did not mean much to her. What really mattered to her? Two things were of monumental importance: her Catholic faith and her Southern identity. On the surface these two things would seem to be incompatible, since the South is largely a Protestant region. But O’Connor was “catholic” in both senses of the term: as I noted earlier, she claims spiritual kinship with Southern Protestants who still believe in spiritual realities. And as an orthodox Roman Catholic, she herself believes in the reality of the spiritual world. Concerning Southern identity, she wrote the following in “The Catholic Novelist in the Protestant South”: “What has given the South her identity are those beliefs and qualities which she has absorbed from the Scriptures and from her own history of defeat and violation: a distrust of the abstract, a sense of human dependence on the grace of God, and a knowledge that evil is not simply a problem to be solved, but a mystery to be endured.”27

Like the Nashville Agrarians who wrote I’ll Take My Stand in 1930, O’Connor did not want to see the South capitulate to modernity or slide into the current of mainstream culture. Her anguish, as theirs, was “caused not by the fact that the South is alienated from the rest of the country, but by the fact that it is not alienated enough, that every day we are getting more and more like the rest of the country.” Like the Agrarians, she was opposed to the modern secular spirit, urbanization, rationalism, and the new Gospel of Progress. She said it was difficult to “reconcile the South’s instinct to preserve her identify with her equal instinct to fall eager victim to every poisonous breath from Hollywood or Madison Avenue.”28O’Connor left no doubt as to which instinct she thought Southerners should follow and cultivate.

Marion Montgomery has noted that O’Connor was a prophet calling us back to known but forgotten truths. As Montgomery observes, she repeatedly remarks that the West’s “spiritual decline set in with the Renaissance [and] that since the eighteenth century in particular our spiritual hungers have been shifted to secular objects, to our general confusion.”29In O’Connor’s analysis, the Enlightenment established the epistemological foundations (shifty and narrow though they be) of modern provincialism. O’Connor’s judgment and vision, faith and reason, her sense of humor and her sense of the tragic—these faculties were not separated by modern enthusiasms: by humanitarianism, rationalism, scientism, and secularism. Her belief informed her wit and vision, and judgment is implicit in her wit and vision. Thus with the absence of sentimentality one finds in the Old Testament prophets, and with the knowledge that “the maximum amount of seriousness admits the maximum amount of comedy,” she wrote her serious comedies. She was concerned with ultimate questions, with Original Sin and grace, with time and eternity, with Heaven and Hell. She rejected the modern secular notion that the only realities are temporal and material. Indeed, her incarnational vision and sacramental theology enabled her to see the spiritual manifested in the physical world around her. She looked at the world from the standpoint of Christian orthodoxy, and I think she rightly noted that this perspective enhanced and enlarged what she saw rather than limited it. 30

Not all readers have been able to stomach O’Connor’s hard comedies. T. S. Eliot, to whom Russell Kirk had recommended O’Connor’s stories, confessed that he “was quite horrified by” the ones he had read. In his letter to Dr. Kirk, Eliot continued: “She has certainly an uncanny talent of high order but my nerves are just not strong enough to take much of a disturbance.”31Eliot is not alone in finding her fiction disturbing. Perhaps some readers of O’Connor’s letters have been disturbed by her wry remarks about religious obligations and pilgrimages and by her criticism of the “average” reader and the normal college audience. But many who are not squeamish have been fixed and fascinated by the power of humor, the clarifying Christian vision, and the blend of comedy and spiritual drama in her fiction.

Notes

1. Mystery and Manners,edited by Sally and Robert Fitzgerald (New York, 1961), 138–140.

2. Ibid.,140.

3. Ibid.,128, 84–85.

4. The second collection, cited frequently in this article, is The Correspondence of Flannery O’Connor and the Brainard Cheneys.

5. The Oxford Companion to Women’s Writings in the United States,edited by Cathy N. Davidson and Linda Wagner-Martin (Oxford, Eng., 1995), 642.

6. The Correspondence of Flannery O’Connor and the Brainard Cheneys,edited by C. Ralph Stephens (Jackson, Miss., 1986), 10, 20, 61–62.

7. The Habit of Being,edited by Sally Fitzgerald (New York, 1980), 49.

8. Ibid.,xi.

9. The Correspondence,32–33, 45.

10. Ibid.,52

11. Page 137.

12. The Complete Stories of Flannery O’Connor,edited by Robert Giroux (New York, 1971), 133.

13. Mystery and Manners,32.

14. “Flannery O’Connor’s Campaign for Her Country,” reprinted in The Correspondence,213.

15. Mystery and Manners,162.

16. Ibid.,185.

17. Ibid.,33–34.

18. Ibid.,112, 117, 118.

19. Ibid.,113.

20. The Complete Stories,500, 508.

21. Ibid.,279, 287.

22. Mystery and Manners,41.

23. Ibid.,207.

24. Ibid.,133, 44–45.

25. The Habit of Being,74, 302–303.

26. Mystery and Manners,26.

27. Ibid.,209.

28. Ibid.,28–29, 200.

29. Why Flannery O’Connor Stayed Home—Volume I in the three-volume work The Prophetic Poet and the Spirit of the Age(La Salle, Ill., 1981), 155–156.

30. Mystery and Manners,167, 175, 178.

31. Kirk Papers. The Russell Kirk Center for Cultural Renewal, in Mecosta, Michigan.

This was originally published in the Winter 2005 issue of Modern Age.