High Noon and Polish Freedom A History of Mutual Respect

The Poster That Symbolizes Shared Values

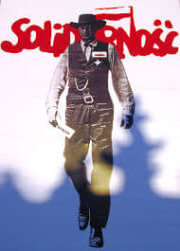

Not many U. S. political scientists I had the pleasure to read or otherwise communicate with know that a poster depicting a character from a famous American Western film became a symbol of the Anti-Communist transformations in Poland in 1989. It was a hallmark of opposition during the election that, as it later turned out, transformed the whole Soviet bloc. A very young graphic artist (22 at the time) named Tomasz Sarnecki decided that a Polish variant of the High Noon poster could serve as an election poster for the democratic opposition bloc in the first semi-free election in Poland since 1945.

According to Sarnecki’s own record, the oppositionists initially were not thrilled, but he consistently lobbied for the idea and it finally gained acceptance.1 The poster was soon to be found all over Poland on every street post and on every wall. It displays the High Noon sheriff, Gary Cooper. In his right hand instead of a gun he is holding a folded ballot saying “Wybory” (i.e. election). On his chest above the sheriff’s badge we see the Solidarity logo (the name of the opposition movement). Below the sheriff there is a sign that announces: “W samo południe: 4 czerwca 1989,” [“High Noon: June 4th 1989.”]

This was not just a mere coincidence. American political culture has been intertwined with Polish republican symbolism for more than two centuries. Moreover, the strong appeal of American democracy was universally recognized in the Western states of the former Soviet bloc. Although initially not universally accepted, over the years the famous Gary Cooper poster has become a symbol of a remarkable, democratizing change that created new allies of the U. S. A. and took place without the death of a single American soldier. This is a fascinating phenomenon especially if one examines the current state of global politics.

Walesa Recalls the Poster’s Influence

In spite some initial misgivings held by the Solidarity leaders concerning the directness and harshness of the message of the poster, Lech Wałesa, the leader of the Solidarity Movement and later the first President of the new nation, has more recently expressed a strong attachment to the “High Noon” poster. In a 2004 interview with the Wall Street Journal Wałesa disclosed:

“I have often been asked in the United States to sign the poster that many Americans consider very significant. Prepared for the first almost-free parliamentary elections in Poland in 1989, the poster shows Gary Cooper as the lonely sheriff in the American Western, ‘High Noon.’ Under the headline ‘At High Noon’ runs the red Solidarity banner and the date–June 4, 1989–of the poll.”

It was a simple but effective gimmick that, at the time, was misunderstood by the Communists. They, in fact, tried to ridicule the freedom movement in Poland as an invention of the “Wild West,” especially the U. S. But the poster had the opposite impact: Cowboys in Western clothes had become a powerful symbol for Poles. Cowboys fight for justice, fight against evil, and fight for freedom, both physical and spiritual.

Solidarity trounced the Communists in that election, paving the way for a democratic government in Poland. It is always so touching when people bring this poster up to me to autograph it. They have cherished it for so many years and it has become the emblem of the battle that we all fought together.2

Poland, Anarchy, and Foreign Intervention

In accordance with Wałesa’s words, the Communist regime before the 1989 election used two arguments with reference to the poster and the whole “Solidarity” campaign. Firstly, it accused the opposition of opting for anarchic“Wild West” politics. Secondly, it voiced the allegation that Solidarity was a puppet of foreign forces.3

Those two imputations very skillfully employed the political sentiments that had been deeply embedded in Polish historical consciousness. The first notion refers to a critique of anarchy as the destructive force that demolishes the state. The second refers to foreign involvement as the final blow to independence following the period of anarchy.

Both anarchy and unfavorable geopolitical circumstances for almost two centuries were presented in Polish political writings, journalism, and historiography as the causes of Poland’s losing its independent statehood. Interestingly, the Polish people are quite aware that the first Polish state collapsed toward the end of XVIIIth century almost exactly at the time when the U S. A. was being founded.

The final demise of the first Polish state is marked by the dismemberment of the republican Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. Not long before then, at the beginning of the XVIIth century, the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, a federated political body, was the geographically largest and one of the most populous states in Europe (stretching from the Black Sea to the Baltic and from Poznan to Smolensk). Later, and up until 1989, Poland was to remain a plaything in the hands of neighboring states–with a short but significant interlude between 1918 and 1939.

The American Founders Learn From Poland’s Trials

Wałesa often mentions that one of the aspects that facilitated the change of 1989 and inspired him personally with courage and faith in success was the supportive and vehemently pro-democratic rhetoric and politics of President Ronald Reagan.4 Indeed, American political leaders were carefully observing not only the rebirth of the new independent Polish state but also the death of the old one.

In the XVIII century, however, the American Founding Fathers saw mainly the flaws of Polish anarchy and its internal weakness. Actually, if one is to trust the record of the Federalist Papers, it seems that the American Framers made a conscious effort to learn from Polish mistakes. The aim was to facilitate the creation of another federal republic, one that avoids the flaws of the Commonwealth but resembles it as far as the sizable territory, large population, and certain political features are concerned.

The authors of the Federalist Papers, in fact, had a stunningly good knowledge of Poland’s history. The Polish state is referred to in five different articles authored by “Publius.” Federalist Papers No. 14 notes, for instance, that the Union can be both substantial in size and republican because “it is not a great deal larger than Germany, where a diet representing the whole empire is continually assembled; or than in Poland before the dismemberment, where another national diet was the depository of supreme power.”5

Federalist Papers No. 19, however, scolds the Commonwealth for having a government that is not unitary enough and forms only a loose cape over the “local sovereigns.” This fact with the word of the author is a striking proof of the “calamities flowing from such institutions.”6 In a word, “equally unfit for self-government, and self-defense, it [Poland] has long been subject to the whims of its powerful neighbors; who have lately had the mercy to disburden it of the one third of its people and territories.”7

Federalist Papers No. 22 in turn refers directly to the famed anarchism of Polish parliamentarism–the liberum-veto rule (we will discuss this a bit later). The article criticizes Poland as the only republic with a “diet, where a single veto has been sufficient to put a stop to all their movements.”8 The very same motif is present in Federalist Papers No. 76,9 whereas Federalist Papers No. 39 criticizes the Commonwealth for being a mixture of “aristocracy and monarchy in its worst forms.”

In fact, the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth since the XVIth century had named itself a Two-Nation Republic, which corresponds with what later became known as the federal or confederal republic. According to Aristotelian terms this was, however, a mixed regime leaning towards a republican constitution with a fully elected King as the chief executive.10

An Ancient Right of Political Participation

The system was said to be based on ancient and Medieval liberties granted to the ancestors of citizens with full voting rights. Having a mixed, unwritten constitution based on political theories of Medieval origin made the Commonwealth also somewhat similar to the British Crown. That is why, in Anglo-Saxon historiography the old Polish-Lithuanian state is usually called a Commonwealth.

As already mentioned, since the XVIth century the state officially named itself a Republic–Rzeczpospolita, and indeed consisted of two main federated bodies, Poland and Lithuania, both with separate treasuries and diets (parliaments) and both with a network of semi-dependent, republican local authorities. Similar to ancient Athens, full citizenship with all political rights was limited and hereditary. Nevertheless, Poland was one of the most populous nations in Europe if we count those who were franchised. In the XVIth century the political participants encompassed 10-12% of all inhabitants of the Commonwealth and up 25% of ethnic Poles. This clearly met the republican standards of the ancient states like Athens or Sparta, where full citizens also did not exceed 10%.11

This political nation was historically called szlachta, a word that has its origin in the word szlachetny, meaning noble. However, it would be a mistake to equate this entire group with the nobility. What the Western Europeans deemed the nobles amounted to less than 1% of Polish szlachta.12 The majority of members of the szlachta possessed only small land plots and many were totally landless. They all, however, derived their liberties from ancient birthrights dating back to the tribal communities that existed before the Xth century or were later ennobled by the king.

A Depleted Treasury Brings Political Weakness

The Polish political nation was the creator of the very first European document forbidding the imprisonment without a trial. The neminem captivabimus nis iure victum law [we shall arrest no one without a court order] was signed by the King in 1430. It, in fact, predated the English habeas corpus act by almost 250 years.13 As in the case of the early Roman Republic, full citizens were expected to appear bearing their own arms in times of war and return to normal occupations in times of peace. They were to be paid in booty only.

Thanks to the peaceful union with the Lithuanian Principality that started with a Medieval, monarchical matrimony and later evolved into full federation, the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth stretched over vast sparsely populated territories of central and eastern Europe. Thus, unlike the Roman Republic, this state did not find itself in continuous warfare.

The ancient method of waging war was, however, ineffective in defending such vast borders. At its height in the early XVIIth century the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth had the largest European territory of all contemporary states. To defend such a vast territory during wars and invasions the Kings naturally heavily depended on mercenaries, and this dependency quickly depleted the treasury,14 there being no political agreement to increase taxation in order to create a modern standing army.

The Infamous Liberum Veto

This treasury was also empty for one more reason–the infamous liberum veto [free veto]. All the changes in law and taxation starting from the XVI century had to be approved by the diet, which was not a permanent body but a gathering of the elected representatives of citizens of respective provinces called on by the King.

New Kings were elected by a general, huge gathering of all full citizens who chose to come to the election. Since the XVI century, during the debate in the legislature, the sejm, the vote had to be in practice unanimous. It was enough for one of the participants of the sejm to say “Veto!” or “Nie pozwalam!” [I do not consent!] to halt the whole legislative process until a compromise was reached or the dissenter got killed in one of the numerous saber duels.15

In a situation of grave danger, it was possible to vote by a simple majority; such a need was, however, rarely seen until the historical sejm that led to the creation of a new constitution of Poland in 1791. It seems that, Lord Eversley, an English Whig historian and politician, rightly calls the liberum veto an “intolerable incubus”16 that paralyzed the assembly, and prevented the executive or legislative action . . .” 17

Carved Up by Prussia, Russia, and Austria

By the year 1750, everything was ready for the final act in the history of the Polish Commonwealth: the partitions performed by the Russian Empire in 1792, the Kingdom of Prussia in 1793, and Habsburgian Austria in 1795. After the last of these dates, the independent states of Poland and the Great Principality of Lithuania ceased to exist.

As British Historian Norman Davies put it:

“To the modern observer, the perspicacity no less than the cynicism of European statesmen regarding the consequence of the First Partition may seem surprising. In a word, where diplomacy was uncomplicated by moral scruples, and where Frederick (king of Prussia) could cheerfully compare his Polish victims to defenseless Iroquois Indians, the deeper effects of the Partition were observed and recorded with cold precision. ‘How blind and insane is Europe to contribute to the rise of a people [the Prussians] which may someday become her own doom.’ ‘The Empress of Russia has breakfasted,’ further warned Edmund Burke, ‘Where will she dine?’ Elsewhere, in reference to the inability of the Western powers to intervene in Eastern Europe. Burke commented that ‘Poland must not be regarded as being situated on the Moon.‘”18

The robust absolutist monarchies of Europe held the Machiavellian trade off between power and freedom to be the sole axiom of effective governance. In contrast, Poland, like the USA, refused to fully accept this trade off. Lord Eversley, writing in the Burkian vein, made a point of revealing the Machiavellian nature of the states that took part in the eradication of what was the last continental remnant of the Medieval republicanism that Tocqueville so mourned.19

Frederick’s Anti-Machiavelli

The English writer starts by sarcastically remarking that “Frederick, in his younger days, just before his accession to throne of Prussia, wrote an able refutation of Machiavelli’s well-known work on The Prince . . . . His book, entitled The Anti-Machiavelli, was enthusiastically applauded by his friend Voltaire . . . “20 According to Eversley’s account, Frederick insisted above all that “a sovereign is bound to observe the same code of morality as other men in private life, and that integrity and good faith must be his sole rule of conduct in public affairs.”21

Frederick’s Anti-Machiavelli was published in the Hague in 1740. Let us quote Lord Eversley once again:

“In the same year, Frederick succeeded to the throne of Prussia. He very soon flung aside the great principles which he had so strongly insisted upon in his book. Beyond any of his contemporary monarchs he was conspicuous for following the precepts laid down in The Prince. Territorial aggrandizement was to him, as to Catherine, the main object of his foreign policy.”22

Later in a letter Frederick explained his actions towards Poland to Voltaire by comparing Poles to to Iroquois that need to be civilized even with the use of unsound methods. Eversely ascribes the faith in the same Machiavellian paradigm to Catherine.

Only when discussing the Habsburgian Empire does the English historian mention that this state, like Poland itself, was a remnant of a bygone era. While the Habsburgs felt they were compelled by necessity to follow the path of Russia and Prussia, they nevertheless valued Poland’s and Lithuania’s roles as buffer-states and in fact owed the very survival of their dominion to the Polish King Jan III Sobieski, who in 1683 led the defense of Vienna and defeated the Turks.23 Still the Habsburgs were not willing to lessen their position of power after the agreement between Russia and Prussia.

Poland Tries an American-Style Constitution

As already mentioned, the political tragedy of Poland became a ghastly memento for all Whigs and Liberals. The American Federalists had used the Polish history as an argument for finding a more perfect union that would still retain a pre-Machiavellian, liberal character. To achieve this, they invented a legal vessel containing the ancient liberties and at same time infusing the government with the strength it needed to defend its territory–a written constitution.

It thus comes as no surprise that the already half-devoured Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth was quick to follow the American example and c0me up with its own Constitution just four years later. This landmark document did away with liberum veto, clearly delineated the powers of the executive, legislative and the judiciary, created a large (on paper) standing army and gave basic immunities to commoners.

On the third of May 1791, the first European written constitution was framed by the Polish diet. It was undoubtedly inspired by the American example, nevertheless, it did not follow the Philadelphian model to the letter. The content of the Constitution was an uneasy compromise between the old Polish laws, the Montesquiean model and other French precepts, some of which were specifically proposed to Poland by Rousseau in Considerations on the Government of Poland.24

Rousseau’s Unsocial Contract Suggestions

In this essay read by the representatives working on the Constitution of the 3rd of May, Rousseau radically limits the application of his Social Contract and diminishes some of his own postulates.25 He advises the Poles to, above all, become well-organized, have a strong legislature, and only then think about liberties. He also urges Poland to content itself with a smaller territory, have a more nationally uniform character and to proceed with expanding liberties onto other social groups with extreme caution.

The Framers of Constitution of the 3rd of May, in line with Rousseau’s advice, did not give full political rights to peasant and burgers of “common” birth. They also created a hereditary Kingship, having in mind the corruption occurring during the traditional elections. Moreover, they gave strong executive prerogatives to the King. Still, in spite of those discrepancies and the apparently illiberal elements, King Stanislaus August, who signed the constitution, described it as “founded principally on those of England and the United States of America, but avoiding the faults and errors of both, and adapted as much as possible to the local and particular circumstances of the country.”26 As it soon turned out the King’s conceit was completely unjustified.

The Hypocritical Justification for Russian’s Invasion

The answer of Catharine the Empress of Russia, who was at that time the official protector of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, was both swift and Machiavellian. While the Russian invasion of what remained of the Commonwealth was naturally foreseeable, the official justification for the invasion remains one of the great diplomatic hypocracies of all time.

Catherine was an absolute ruler of one of the least liberal countries on the continent. Nevertheless, she did not hesitate to announce that after the passing of the Constitution of the 3rd of May, it is:

“necessary to restore the Polish liberty in its ancient lustre, to ensure the elective rights of the monarchy, and to destroy foreign influence, which was rooted in the State and which was the continual source of trouble and contest.”27

The above quotation comes from an official proclamation by Catherine and a group of her Polish supporters from the Targowica Confederacy, whose position in Polish history can only be compared to that occupied by Benedict Arnold in America history.28

The Russian invasion naturally crushed the weak new state. Nevertheless, already by 1794 a major insurrection had broken out. Its commander in chief was no one else but Thadeus Kosciuszko, the Polish general who had served on Washington’s staff in the U. S. Continental Army.29 Kosciuszko, like Casimir Pulaski and other Polish volunteers, came to America as soon as they learned of the Revolution [From the fall of the Polish state up to the 1990’s, many Polish immigrants came to the U. S., finding a new home in the more perfect federal republic. According to the 2000 U. S. Census Bureau data, there were about 10 million Polish Americans, representing 3.2% of the population of the United States.30 ].

Mixed Feelings about an Unhappy History

As we have already mentioned, the defective governance and especially the infamous liberum veto attached a stigma of anarchism to Polish political culture. In some historical schools, this actually developed into an outright critique of republicanism and a defense of the enlightened Habsburgian monarchy. This point is vociferously made by the so-called Krakow School of historians.31

Currently this tradition results in a kind of political schizophrenia and hypersensitivity to historical issues on the part of many Polish politicians, public figures, and writers.32 On the one hand, many Poles, just like other nationals, try to be proud of their history; on the other hand, they are painfully aware that some of the symbolisms they theoretically hold to be the most valuable in practice had led to the fall of the first Polish state.33

This paradox results from the fact that Poland tried to go against the logic of the Machiavellian era that started in the West about 500 years ago. As a consequence the Polish state suffered a bitter defeat. The USA was more successful and now expresses its success as “exceptionalism.”34 Polish historical consciousness, in contrast, is largely based on a political inferiority complex. For instance, recent statistical polls show that out of all the European nation the worst opinion about the Poles is held by . . . . the Poles themselves.35

The Easternmost Western State

In spite of some anti-liberal and monarchic yearnings republican symbolism turned out to be a very resilient element of Polish history. During the period of partitions this constantly led to conflict between the Polish population and the leadership of the absolutist states. Political unrest and numerous rebellions were common in the lands inhabited by the Poles throughout the whole 19th century. The roots of Polish political experience was fundamentally different from that of other nations and especially different from the Russian.

At the same time, in accordance with the already mentioned historical factors, Polish political culture and its symbolism became reminiscent of American Republicanism. Returning to more recent history, let us not forget that in accordance with Wałesa’s words, Polish transformation was facilitated by two actors remembered for their Western roles–Ronald Reagan and Garry Cooper.

Perhaps the inherent anarchic and rugged individualism of the Westerns corresponded with the Polish political culture even better that the cautious and studied science of government presented by the American founding fathers. Nevertheless, both republican culture codes were present in the Polish tradition. One cannot help but ask the rhetorical question: Could a sheriff with a ballot in his hand become a powerful political symbol in Russia?

The Black Knight Effect

If one doubts whether there is a qualitative difference between political cultures of the East and West or Europe and Asia one should examine two states as a case study–namely Russia and Poland.Immediately it will become apparent that ethnically and linguistically the people of both countries are very similar. Nevertheless their political cultures diverged greatly due to the choices that had been made over the course of centuries as well as the results of the unpredictable elements in history–such as the Mongolian invasion of Kievian Russia in the 14th century.As a result, Poland clearly remained an east-most Western country and Russia, along with its ally, Belarus, the east-most Central-Asian state.

This conclusion is consistent with empirical research. In their recently published book, Competitive Authoritarianism,Levitsky and Way, for instance, test a hypothesis to explain why certain Post-Communist states have democratized better than others.36 Apart from the fairly familiar set of domestic variables such as the strength of government, the structure of the government’s resources, the organizational power of the opposition, etc.,37 they also focus on links to the West and its influence [which the authors term “leverage”].38

In fact, in their analysis the external influence seems to be a force so strong that it can overcome the domestic factors. The authors write that “in states with extensive ties to the West, post-Cold war international influences were so intense that they contributed to democratization even where domestic traditions were unfavorable.”39 The authors measure that influence by examining “economic, intergovernmental, and technocratic (education in the West) linkages as well as social connections (tourism etc.).”40 The “leverage,” on the other hand, becomes important when existing links are used to influence democratic change.

At a certain point the authors look at a phenomenon they call “the black knight effect.”41 They mean by this term that, according to some data, the linkage and leverage of Russia, among other states, has a significant anti-democratic effect. This comes as no surprise to a student of the history of politics. The notion of the so-called “close foreign lands” is deeply embedded in Russian political culture.42 As the old Russian saying goes: “The Chicken is not a bird, and Poland is not a foreign country.” Indeed, from Moscow’s point of view not allowing its immediate neighbors to become westernized is still viewed as a vital part of the country’s defense strategy.43

The question remains why Moscow failed to create a strong “black knight effect” among the Balts, Poles, Czechs, Hungarians and East Germans. An immediate answer would be that Russia and Russians were not very popular, not to say despised and hated, among members of those national groups. Conversely, among the same communities, during the transformation of the late 80’s, the West was somewhat gullibly hailed as a symbol of all that is positive in politics. This answer is obvious for anyone who had spent at least a part of the late 80’s and early 90’s in the western parts of the Former Soviet Bloc.

The Russians and “The Barbarian Effect”

Nevertheless, this effect is not completely captured by Levitsky’s and Way’s model that focuses only on easily measurable ties. In fact, in the 80’s economic connections with USRR were dominant. The last members of the intellectual elites, who were educated in the West before the Second World War, were slowly passing away and “tourism” was suppressed:

“Moreover, the Western states initially did not actively try to become popular in the Soviet Block or to pressure Russia. Still at the time, the West was perceived very positively and the USRR generally disliked. The more elaborated explanation of that phenomenon seems clear, albeit it may strike certain people as not politically correct. In the Western parts of the Soviet empire the Russians were never viewed as a civilizing force even if they may have been so viewed in central Asia and some underdeveloped parts of Bielarus and Ukraine. From the Point of view of the Balts and Central Europeans, Russians were essentially looting barbarians. Before the first Russian invasion those countries had their own cultures–both political and intellectual–which their citizens viewed as superior to anything Russia could offer. In the case of Poland the first Russian invasion took place quite early–at the end of 18th century. Even at that time, according to Miłosz, for a well-born Polish lady to marry a Russian officer led to social death while the same fate did not befall her if she became the mistress of a French General.”44

After a brief period of independence, came the second invasion than is sometimes deemed “liberation,” since it occurred after the war, in 1945. In many people’s memories from this period certain events keep recurring.45 The Russian soldiers stole watches, utilized porcelain chamber-pots as soup bowls, took window curtains to use for making clothes, got stone drunk and harassed or raped women. This is a very different memory from the Western-Europe’s image of an American occupation soldier as a man who dispensed chewing gum and chocolate to neglected children or, equipped with a brand new pair of nylon stockings and a bouquet of flowers, became a charming womanizer.

The perception of Russian troops in Central Europe illustrates what I would call the “barbarian effect” in comparative politics. It is a strong negative stereotype which is formed after occupation or “colonization” and which later becomes very hard to overcome. Naturally, the matter is more complicated in countries like Japan, whose society obviously did not view Americans as superior, but acknowledging their defeat and political short-comings, adopted selectively certain elements of American political culture. Nevertheless, I believe that the “barbarian effect” hypothesis holds true for most cases. It seems that military victory and even economic preponderance is simply not enough to instigate cultural linkage, if one of the cultures obstinately perceives itself as superior.

High Noon, the Poster, and the Elections

Part of the appeal of American culture to the Poles cannot be explained as a “civilizing effect.” It was rather a result of the strong individualism rooted in Polish political symbolism. The tradition of liberum veto somehow corresponded with the rugged frontier spirit of the Wild West sagas. As the designer of the poster pointed out the films was widely known and positively perceived by the viewers.46 The picture was released in 1952. It describes an aging sheriff (Garry Cooper) who must face a gang leader who he had already once before brought to justice. The showdown actually takes place just as the Sheriff is preparing to end his career as a man of law.

Politically, the most prominent element of the film is the behavior of the town’s people, who turn their back on the sheriff when he asks them for help. They do so in spite of the fact that the sheriff had risked his life on many occasions to preserve order in the town. This situation forces Will Cane (the sheriff) to confront the outlaw and his gang all alone, in an empty, silent street. The sheriff ultimately triumphs with the aid of his young wife, who, being a Quaker must overcome the moral dilemma of whether to shoot a human being or to let her husband be killed. After the final showdown, the townspeople emerge from hiding into the street. The sheriff contemptuously throw the star at their feet and walks away.

Ironically, the US movie industry’s insiders with strong Anti-Communist views did not initially appreciate the film. John Wayne famously said that the picture was “the most un-American thing” he had ever seen in his “whole life.”47 He claimed this because at the time the movie was seen as criticism of blacklisting some film industry employees accused of Communist sympathies. The House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) famously questioned and in various ways tried to intimidate the High Noon’s screenwriter Carl Foreman. Jeremy Byman explores all those issues in detail in his book devoted largely to the Anti-McCarthyistic interpretation of High Noon. Byman nevertheless notes:

“But for most ordinary moviegoers in 1952, Foreman’s interpretation, whether of Hollywood or HUAC, simply did not register. For one thing Garry Cooper screen persona, developed in the sentimental-traditionalist films of Frank Capra, confused the issue of conventional social criticism, especially because he was an individual standing up to betrayal. For another, the film’s abstractness permitted many interpretations. In the Midwest for instance, Cooper was seen as a symbol of Eisenhower working against the Communist threat, a view Eisenhower presumably himself adopted with his numerous White House screenings of the film. . . . At the other end of the political spectrum, the Soviet Union’s Communists Party newspaper Pravda attacked the film as a “glorification of the individual.”48

Polish Individualism and “The Sheriff’s Star”

It is precisely this individualism that appealed to the Poles in 1989. In fact, the political reception of the sheriff-motive was already present in Polish underground popular culture for some time. About twenty yearsbefore, Stanislaw Staszewski–a singer associated with the Polish democratic underground and a veteran of the Warsaw Uprising of 1944, had already written and performed a political song about the brave sheriff.49

According to Rogulska the text of the song entitled “The Sheriff’s Star” is loaded with political undertones pertaining to Poland and urging the people to be the sheriffs in their own town-country.50 One may add that with all probability those lyrics were also inspired by “High Noon,” which was widely screened in the countries of the Soviet Block.

In fact, it was one of the few American Western films that in spite of its “glorification individualism” was given a green light by the Communist censorship. The reasons for that fact are unclear, however, it seems that the criticism of McCarthyism and blacklisting of the American left played a certain role and made the film more “correct” in the eyes of the Communist censors. Naturally, the audience did not look for those minute undertones and interpreted the film as fundamentally anti-Communist.

One of Staszewski’s famous stanzas proclaims:

Kup bilet i na western śpiesz,

Gdy się nie cieszysz życiem–to się śmiercią ciesz.

A kiedy błysną światła, zmilknie kamer szum,

Spójrz na ulicę–to szeryfów stąpa tłum.

Obejmij dłonią kolbę, palcem zmacaj spust,

Bądź czujny i nic nie mów, ani pary z ust.

Choc’ nawet zegar dziejów bije smutny ton,

To twoje serce prawdę mówi–a nie on.

[Buy Your ticked now to see the Western,

May death bring You happiness if life makes You stern,

And when the lights are on and the projector’s off,

Look at the Street, there is a crowd of sheriffs walking,

Now put your hand round the pistol as you come,

Touch the trigger, be silent tell no one,

And even if the clock of history rings a sad tone,

Remember, it is wrong and your heart’s right on.

(my translation).51

Although the opposition leaders were not certain of the election outcome at the time the poster was printed, they did expect a dire duel with the communist propaganda machine. This is one of the reasons why their political narrative sought to convince each voter that he or she needs to be the lone sheriff who fights regardless of what the other townspeople do.

In other words the citizens were asked to resist the gang even if it is merely a liberum veto. Naturally, everyone wanted to be the sheriff, the result was startling even for the most optimistic among the opposition leaders. Of all available seats, the Solidarity block gained 160 of 161 seats in the lower chamber of parliament and 92 of 100 seats in the upper chamber.52 This was one of the greatest landslides in any democratic election. There were, indeed, many millions of “sheriffs walking.”

References

Byman, Jeremy. Showdown at High Noon. Lanham: Scarecrow Press, 2004.

Cichy, Michał. “1945 Koniec i Poczatek” [1945 the End and the Beginning], Gazeta Wyborcza, May 26 1995.

Davies, Norman. God’s Playground, A History of Poland, vols 1 and 2, New York: Columbia University Press, 1982.

Eversley, Lord George Shaw-Lefevre. The Partitions of Poland, London: T. Fisher Unwin, Ltd., 1915.

Federalists. The Federalist Papers. Indianapolis: Liberty Fund, 2001.

Friedman, George. The Next 100 Years. New York: Anchor Books, 2010.

High Noon. DVD. Directed by Fred Zinnermann. New York: United Artists, 1952.

Jaseinica, Pawel. Polska anarchia [Polish Anarchy]. Wydawnictwo Literackie: Krakow, 1988.

Kucharzewski, Jan. The Origin of Modern Russia. New York: The Polish Institute of Arts and Sciences in America, 1948.

Lemon Press Center. “Plakat Wyborczy z 1989 r” [Electoral Poster form the year 1989]. http://www.prasowe.com/plakat-wyborczy-z-1989-r-wideo/, 2011.

Levitsky, Steven and Lucan A.Way. Competitive Authoritarianism. New York: Cambrigde University Press, 2010.

Kasparek, Joseph. The Constitutions of Poland and of the United States: Kinships and Genealogy, Miami, FL: The American Institute of Polish Culture, 1980.

Lipset, Seymour Martin. American Exceptionalism: A Double-Edged Sword. New York: Norton. 1997.

Miłosz, Czeslaw. Czlowiek Wsrod Skorpionow [The Man Among the Scorpios]. Warszawa: Znak, 2000.

Pula, James S. Thaddeus Kosciuszko: The Purest Son of Liberty. New York: Hippocrene Books, 1988.

Richmond, Yale. From Da to Yes, Understanding the Easter Europeans, London: Nicholas Brealesy Publishing, 1995.

Rogulska, Agnieszka. “Staszek Staszewski–Poeta Podziemia Ery Gomułkowskiej” [“Staszek Staszewski–The Poets of the Political Underground of the Gomulka Era”]. Biultetyn Instytutu Pamieci Narodowej vol. 10, no. 21: 58-64, 2002.

Rousseau, Jean Jacques. Considerations on the Government of Poland. In: Rouseeau, Jean Jacqued. 1997. The Social Contract and Other Political Writings. Edited by Victor Gourevitch. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997.

Roszkowski, Wojciech. Histora Polski 1914-1990 [History of Poland 1914-1990.]Warszawa: PWN, 1992.

Szujski, Jozef. “O falszywej historii jako mistrzyni falszywej

polityki.” Edited by Michalak Henryk.Warszawa: Panstwowy Instytut Wydawniczy, 1991.

Tocqueville, Alexis de. The Ancien Regime and the Revolution. Translated and edited by Gerald Bevan. London, England: Penguin Books, 2008.

U. S. A. Census Bureau. “2000 Census.” http://www.census.gov/. 2010.

Walesa, Lech. “In Solidarity.” The Wall Street Journal. 11 June 2004.

Weidhorn, Manfred. “High Noon.” Bright Lights Film Journal (2) 2005.

Ziemkiewicz, Rafał. Polactwo [‘Polakishness’], Warszawa: Fabryka Słow, 2004.

Notes

1. Lemon Press Center. 2011. “Plakat Wyborczy z 1989 r.” [“Electoral Poster from the year 1989”]. http://www.prasowe.com/plakat-wyborczy-z-1989-r-wideo/.)

2. Wałesa, Lech. 2004 “In Solidarity.” The Wall Street Journal. 11 June 2004

Weidhorn, Manfred. “High Noon.” Bright Lights Film Journal (2) 2005.

3.Roszkowski, Wojciech. 1992. Histora Polski 1914-1990 [History of Poland 1914-1990]. Warszawa: PWN., 405.

4. Wałesa, Ibid.

5. The Federalist Papers. Indianapolis: Liberty Fund, 2001, 64. All the contirubutors to the Papers, James Madison, Alexander Hamilton, and John Jay, wrote under the nom de plum, Publius. No.14 was written by Madison.

6. Ibid., 94.

7. Ibid., 94.

8. Ibid., 108.

9. Ibid., 384-391.

10. See Davies, Norman. God’s Playground, A history of Poland, vols 1 and 2, New York: Columbia University Press, 1982.

11. Richmond, Yale. From Da to Yes, Understanding the Easter Europeans, London: Nicholas Brealesy Publishing. 1995, 51.

12. Ibid.

13. Davies, 136.

14. Ibid.

15. Jaseinica, Pawel. Polska anarchia [Polish Anarchy]. Wydawnictwo Literackie: Krakow, 1988.

16. Eversley, Lord George Shaw-Lefevre. The Partitions of Poland, London: T. Fisher Unwin, Ltd.,1915, 37.

17. Ibid., 22.

18. Davies, Norman. God’s Playground, A History of Poland, vols 1 and 2, New York: Columbia University Press, 1982, 1:524.

19. Tocqueville, Alexis de. The Ancien Regime and the Revolution. Translated and edited by Gerald Bevan. London, England: Penguin Books, 2008, 29 ff.

20. Eversley, Lord George Shaw-Lefevre. The Partitions of Poland, London: T. Fisher Unwin, Ltd., 1915, 30.

21. Ibid., 31.

22. Ibid.

23. Ibid., 33.

24. Rousseau, Jean Jacques. Considerations on the Government of Poland. In: Rouseeau, Jean Jacqued. 1997. The Social Contract and Other Political Writings. Edited by Victor Gourevitch. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997.

25. Kasparek, Joseph. The Constitutions of Poland and of the United States: Kinships and Genealogy, Miami, FL: The American Institute of Polish Culture, 1980.

26. Ibid., 40.

27. Eversley, 58.

28. Jaseinica, Pawel. Polska anarchia [Polish Anarchy]. Wydawnictwo Literackie: Krakow, 1988, 71.

29. Pula, James S. Thaddeus Kosciuszko: The Purest Son of Liberty. New York: Hippocrene Books, 1988.

30 .U. S. A. Census Bureau. “2000 Census.” http://www.census.gov/. 2010.

31.Michalak, Henryk. O falszywej historii jako mistrzyni falszywej polityki

Josef Szujski ; wyboru dokonal, przygotowal do druku i wstepem opatrzyl

.Warszawa: Panstwowy Instytut Wydawniczy, 1991.

32. Ziemkiewicz, Rafał. Polactwo [‘Polakishness’], Warszawa: Fabryka Słow, 2004, 5-30.

33. Ibid., 8-9.

34. Lipset, Seymour Martin. American Exceptionalism: A Double-Edged Sword. New York: Norton. 1997.

35. Ziemkiewicz, 13.

6. Friedman, George. The Next 100 Years. New York: Anchor Books, 2010.

37. Ibid., 68-82; 381-493.

38. Ibid., 36-44; 372-381.

39. Ibid., 38.

40. Ibid., 43.

41. Ibid., 41.

42. Kucharzewski, Jan. The Origin of Modern Russia. New York: The Polish Institute of Arts and Sciences in America, 1948, 225 ff.

43. Friedman, op.cit., 66.

44. Miłosz, Czeslaw. Czlowiek Wsrod Skorpionow [The Man Among the Scorpios]. Warszawa: Znak, 2000.

45 .Cichy, Michał. “1945 Koniec i Poczatek” [1945 the End and the Beginning], Gazeta Wyborcza, May 26 1995.

46. Lemon Press Center. “Plakat Wyborczy z 1989 r” [Electoral Poster form the year 1989].

47. Weidhorn, Manfred. “High Noon.” Bright Lights Film Journal (2) 2005.

48. Byman, Jeremy. Showdown at High Noon. Lanham: Scarecrow Press, 2004, 94.

49. The precise date when the song is was created is uncertain. The most likely version (Rogulska 2001 and Tata Kazika 1992) is that Stanislaw Staszewski (1925-1973) started perfoming the song in the early ’70’s.

50. Miłosz, Czeslaw. Czlowiek Wsrod Skorpionow [The Man Among the Scorpios]. Warszawa: Znak, 2000.

51. See footnote 49.