History as Progress or Reversal? The Mythical Prognostications of Kojève and McLuhan

Introduction

The “End of History,” as the Marxist philosopher Alexandre Kojève argued, signified the triumph of rational atheism in which man makes himself God and abolishes the slavish mythology of religion. Yet the current resurgence of religious belief in the present age has demonstrated that History has not progressed to the point of abolishing religion. Is History, then, still progressing towards an enlightened atheism or reversing direction by returning to the religious hegemony of a past age? In order to answer this question, I shall compare and contrast Alexandre Kojève and Marshall McLuhan’s distinctive prognostications on the future of religion in the present age. The paradox to which McLuhan points is that religion becomes stronger as the forces of technological modernization gather strength. Christian myth in particular, as McLuhan argues, is experiencing a revival at the expense of belief in Progress precisely because the unsettling nature of technological change is more comprehensible to the mythical-religious mind that rejects the progressivist myth that human beings are motivated by economic self-interest alone. Despite his occasional overtures to Christian triumphalism, McLuhan’s paradoxical hermeneutic shows how religious myth is best suited to understand the conflicts of our age. McLuhan’s reflections also vindicate Eric Voegelin’s perspective that anxieties over tribalism are more intelligible to the religious mind than to a progressivist one.

Kojève’s Philosophy of History

The field known as the “Philosophy of History” has fallen on tough times in recent history. This field, which distinguishes “History” from the mere study of historical fact, typically makes two assumptions. First, there is a discernible direction to History. Second, philosophers are in a unique position to understand this direction. Both premises, to say the least, are questionable. With respect to the first, History has been full of surprises for those prophets who claimed to know the future. In the nineteenth-century, it was fashionable to believe that History was the story of unending, if gradual, progress towards scientific advancement and mass enlightenment.[1] Out of this progress would arise a more peaceable, moral, and prosperous world. In the last century, however, two world wars, economic depression, and totalitarian violence effectively shattered this progressivist myth. Although scientific advancement has created many technological conveniences, it has not yet furnished the wisdom with which to employ these tools.

With respect to the second premise, even the most enthusiastic philosophers of History have recognized that their unique position in diagnosing the future of History is limited, if not hampered, by what Marshall McLuhan called the problem of the rear-view mirror: “we are always one step behind in our view of the world.”[2] That is to say, human beings can only understand History after it has already happened. Their perspective is a retrospective. As Hegel once famously observed the Owl of Minerva flies at dusk.[3] If the direction of History can only be understood after it happens, it seems absurd to predict the future based on the past. To deny this fact is to be oblivious of Hume’s famous warning that there is no necessary connection between sunrises in the past and a sunrise tomorrow.

Despite these well-known objections, it may be too hasty to conclude that the Philosophy of History has been tossed into the dustbin of history. After all, politicians on both sides of the ideological spectrum today still accuse their opponents of being on the “wrong side of History,” as if they knew the direction of History and even knew which side was right. Moreover, the old progressivist version of History still has its adherents. The assumption that democracy is the political manifestation of real progress still commands widespread support in the Western world and beyond. When Francis Fukuyama declared the “End of History,” after the fall of Soviet Communism in the early 1990s, he was, as a neoconservative, defending the Left-Hegelian view that liberal democratic capitalism had ultimately defeated its enemies on the Left and Right by making freedom and prosperity universal for millions of people around the world.[4] Even if failed wars for democracy in Iraq, Libya, and Afghanistan have chastened this hope, it has not vanished altogether.

One of the most powerful hopes, if not expectations, that has always been part and parcel of the Left-Hegelian narrative has been the prediction that religion itself would disappear with ever increasing progress. If it is true, as Marx believed, that religion was the opiate of the masses, an illusion that falsely comforted the oppressed with promises of justice in Heaven while they endured Hell on earth, it followed necessarily that the elimination of oppression (class divisions) would also signal the end of religion. Despite the fact that most of Marx’s prophecies have not been fulfilled, his followers have been loath to abandon his prediction that religion will one day become obsolete.[5] Kojève, one of the most famous interpreters of Hegel in the twentieth-century, is no exception here. To be sure, he was not a typical Marxist, given his belief that American capitalism, even in the 1930s, had “already attained the final stage of Marxist communism.”[6] (He even praised Henry Ford as the greatest Marxist who ever lived.[7]) Despite his rejection of Marx’s identification of economic progress with the triumph of communism, however, Kojève enthusiastically shared Marx’s view that religion was quickly becoming a thing of the past.

In his famous lectures on Hegel’s Phenomenology of Spirit that he gave at the École pratique des hautes études in the 1930s, Kojève went so far as to read into Hegel an utter rejection of religion’s longevity. Religion, including Christianity, was merely an unconscious anthropology, an unreflective attempt by humanity to project all of its hopes and dreams onto an imaginary deity. Put in Kojève’s terms, the first religion was natural (or pagan) religion (God without man), the first atheism was comedy as articulated by Aristophanes (man without God), then came Christianity (God making Himself man), and finally, the second atheism arrives, that of Hegelian wisdom (man making himself God).[8] Even though Kojève was downplaying the more conservative elements of Hegel’s Phenomenology, particularly the latter’s many allusions to the necessary survival of Christianity as a leavening influence,[9] he was convinced that the first great philosopher of History would not ultimately fall back into the primitive ignorance that constitutes the religious mind. Although Hegel’s metaphysical anthropology preserved the essence of Christian theology, his philosophy was incompatible with theism. (There was no way that “Spirit” was identical to “God” according to Kojève’s Hegel.[10]

It was inevitable, then, that religion would become a marginalized, if not extinct, force in modernity. With particular attention to the master-slave dialectic that Hegel explains in the Phenomenology, Kojève averred that it was both rational and necessary that man would inevitably achieve self-consciousness, after a long drawn out violent process in which the slave struggles against the master for recognition. All this would lead to the abandonment of religion. With history’s finale, the refutation of religion would be complete. This ending signified the triumph of rational atheism in which man makes himself God and abolishes the slavish mythology of religion in favor of bourgeois individualism and self-consciousness.[11]

Note that Kojève was not denying that at one time in history religion had served a critical purpose. Christianity, in particular, was the first universal religion that came closest to bringing about true self-consciousness by teaching that all human beings are equal as well as finite: “the whole evolution of the Christian world is nothing but a progress toward the atheistic awareness of the essential finiteness of human existence.”[12] The Christian faith was the first religion to discover the spirituality of man as free, individual, and historical. This synthesis of the particular and universal as well as the related recognition of theology as anthropology, became possible only in the form of Christian individuality, Christ as man-God.[13] Yet this religious consciousness lacks true (or political) wisdom. The particular problem is that the religious man thinks that God, not the State, is universal and homogeneous at any time in history. Hence he erroneously believes that he can attain absolute knowledge at any historical moment whatsoever, whereas he can only attain the State (not God), and only at the End of History.[14] Unbeknownst to the religious man, only the universal homogeneous state, the final achievement of equality for all on earth, realizes the Christian ideal of charity (love of all human beings as one would love God).[15]

The fact that Christianity had once served this useful purpose did not mean, according to Kojève, that this religion needed to stick around in order to reveal the message of human equality. Once modern rationalism had exposed Christianity as a myth, however useful, the game was done. In a review essay of works by his friend Fr. Gaston Fessard, Kojève wrote:

“he [Fessard] has perhaps shown that man must believe in a God-Man if he wants to believe in such a meaning in history. In other words, he has at the very most shown that the idea of a (definitive and ‘absolute’) goal of history—and consequently my action within it—necessarily implies, even for a Hegel or a Marx, a more or less Judeo-Christian myth. And he can, I believe, be granted that. But the misfortune is that a myth which knows itself to be a myth is longer a ‘myth,’ but more or less a ‘fable,’ conventional or not.”[16]

In short, now that the universal homogeneous state has achieved equality for all, the egalitarian religion of Christianity has become historically unnecessary. Still, is it obvious that Left-Hegelianism has triumphed to the point of rendering this faith obsolete?

McLuhan’s Philosophy of History

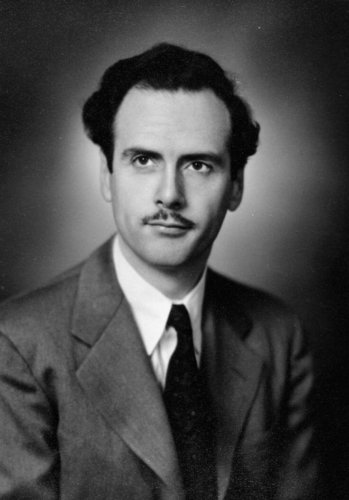

One twentieth-century thinker that comes close to providing a Right-Hegelian response to this Left-Hegelian narrative on the death of religion in our time is Marshall McLuhan. I use the appellation “Right-Hegelian” advisedly because McLuhan did not primarily see himself as a philosopher, nor did he show any explicit sympathy for Hegel. However, McLuhan as much as Kojève thought in historical terms. Despite his doubts about grand theories of history, McLuhan was not reluctant to engage in some historical periodization of his own. As I have argued elsewhere, McLuhan even owes a subtle debt to Hegel.[17] What is most relevant to my purpose here is McLuhan’s theological challenge to the modern secular dismissal of religion as a spent and obsolete force.

It is advisable to understand McLuhan as a paradoxical thinker who embraced tensions and contradictions without hesitation. There is no obvious system in his vast oeuvre of works on the impact of mass media throughout history. Instead, the reader discovers a myriad of insights that, at first glance, contradict each other. McLuhan shows his great debt to historical thinking when, almost in progressivist terms, he presents History as a variation of the Christian story in terms of “the mythical typology of Fall and salvation. The full thrust of the theory is found in a tribalism-detribalization-retribalization triad.”[18] In the beginning of history, human beings spoke and sang: there was no written word or symbol. They related to one other as members of a tribe, valuing unity over individuality. Then came the age of detribalization, brought on by the rise of writing and print, which turned human beings into private individuals living a fragmented existence. Finally, the onset of electric media, beginning with the telegraph in the mid-nineteenth-century, ushered in the global village, a new age of unprecedented interconnectedness that retribalizes the world.[19] What Yoram Hazony aptly describes as the “bonds of mutual loyalty that hold firmly in place an alliance of many individuals, each of whom shares in the suffering and triumphs of the others” fits perfectly McLuhan’s understanding of tribalism.[20]

Still, was this movement of history identical to progress? Not necessarily. McLuhan’s stage theory of history is in part indebted to a classical or premodern account of time. In Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man (1964), McLuhan shows how technological change does not simply advance history so much as it reverses it. The ancient Greek concept of reversal is central here. “In the ancient world the intuitive awareness of break boundaries as points of reversal (and no return) was reflected in the Greek idea of hubris, which Toynbee presents in his Study of History, under the head of the ‘Nemesis of Creativity,’ and ‘The Reversal of Roles.’ The Greek dramatists presented the idea of creativity as creating, also, its own kind of blindness, as in the case of Oedipus Rex, who solved the riddle of the Sphinx.”[21] The tragic and fatalistic implications of this passage are obvious. Once again, McLuhan emphasized that human beings are generally ignorant of the effects of technology until it is too late. “Whereas in the mechanical age of fragmentation leisure had been the absence of work, or mere idleness, the reverse is true in the electric age. As the age of information demands the simultaneous use of all our faculties, we discover that we are most at leisure when we are most intensely involved, very much as with the artists in all ages.”[22] Naturally, we make this discovery after the fact, in accord with the logic of the rearview mirror.

Yet the new age of electric media has ushered in a comparably revolutionary period of transformation, one that came with some good news for humanity. The possibility of reconciliation between human beings who were separated from each other in the print age might even occur. (Perhaps this version of reversal is analogous to Hegel’s idea of “inversion,” or the reconciliation of opposites.[23]) Politics is now participatory, not secretive. Like the Catholic Mass, the new media have closed the gap between rulers and ruled. “On this planet, the entire audience has been rendered active and participant.”[24] People, especially youth, no longer wish to conform to the mass individualism of the print age. These youth wanted “roles,” not slots in an administrative machine. In short, the age of Machiavelli was over.

The young have abandoned all job-holding and specialism in favour of corporate costuming and role-playing. They are in the exact opposite position of Hamlet, who lived in an age when roles were being thrown away, and Machiavelli and individuals were emerging. Today, Machiavelli has been thrown away in favor of role-playing once again.[25]

Yet this “tribalistic” world, which encourages corporate identity and role-playing at the expense of private and individualistic identities, would not witness the end of religion. The secret and administrative nature of the Church, we have seen, would give way to the demand for a more involving and participatory faith.[26] New religious identities are created from below rather than imposed from above. Predictions that religion would disappear with the rise of secularism are dead wrong. As the electric technologies of TV and the computer extend consciousness, a new age of faith would emerge: “I think that the age we are moving into will probably seem the most religious ever. We are already there.”[27]

Most significantly, McLuhan hoped that only one religion can help human beings survive these momentous changes. As old identities are destroyed and new identities are created in equally violent ways, rationalism would be far less appealing than faith. “It is not brains or intelligence that is needed to cope with the problems which Plato and Aristotle and all of their successors to the present have failed to confront. What is needed is a readiness to undervalue the world altogether. This is only possible for a Christian.” These worldly changes would overwhelm the secular mind who “struggles to escape from this new pressure,” but not the Christian. “Thus war is not only education but also a means of accelerated social revolution. It is these changes that only the Christian can afford to laugh at.”[28] How, exactly, though, did the Christian of the electric age withstand these pressures with greater success than anyone else?

McLuhan’s answer to this question is that Christians will make bold use of their new power, armed with the electric media, to transform their own faith tradition in a manner that, he believed, was closer to the original (premodern) participatory nature of the Church, before it became hopelessly bureaucratized. McLuhan thus attributed great transformational power to believers in the Church. “In Jesus Christ, there is no distance or separation between the medium and the message: it is the one case where we can say that the medium and the message are fully one and the same.” Electric media would fulfill the promise of Christianity at long last:

“In fact, it is only at the level of a lived Christianity that the medium really is the message. It is only at that level that figure and ground meet. And that also applies to the Bible: we often speak of the content of Scripture, all while thinking that this content is the message. It is nothing of the sort. The content is everybody who reads the Bible: so, in reading it, some people “hear” it and others don’t. All are users of the Word of God, all are its content, but only a small number of them discern its true message. The words are not the message; the message is the effect on us, and that is conversion.”[29]

What, then, would be the most important effect of this transformational fulfillment of the Christian message in the age of television and the computer? McLuhan hoped that the famed “global village” would accomplish what the medieval Church had only imagined: the Christian unity of mankind. (This is reminiscent of the “universal homogeneous state.”) This messianism was so rooted in McLuhan’s thought that there are even traces of it in his early works, before he became famous in the 1960s. In his 1954 lecture, “Catholic Humanism and Modern Letters,” he mused that the medium of poetry, as long as it is informed by Catholic humanism, may lead to “the transformation of all common life and politics” which may then provide “the intellectual matrix of a new world society.”[30]

Ten years later, McLuhan elaborated upon this theme in Understanding Media, in which he emphasized our electric media had united humanity as never before. “In the electric age we wear all mankind as our skin.”[31] Furthermore, McLuhan replaced poetry with electric media as the revolutionary force that might fulfill the old (Catholic) dream of a unified human family: “might not our current translation of our entire lives into the spiritual form of information seem to make of the entire globe, and of the human family, a single consciousness?”[32] In his private correspondence during this later stage of media studies, McLuhan was even more explicit in his emphasis on the electric media’s fulfilment of the Christian message:

“Another characteristic of man’s humanity is his freedom in community, which the Christian community provides. Christian freedom is found in the corporate freedom in the mystical body of Christ, the Church. The electric age has so involved man with his whole world that he has no individual freedom left. He only has a corporate freedom in the tribal context. The hope of man is that he can be changed sacramentally so that he will eventually come to an awareness of himself in his community and discover individual freedom in the community.”[33]

In historicist fashion, McLuhan was distinguishing between the old individualistic Greco-Roman Christianity and the new tribalist participatory Christianity of the new age. McLuhan also followed a historicist logic when he associated the truth of Christianity with its institutions over time. Yet this distinction between ancient and modern Christianity was not simply based on the need to differentiate political manifestations of the Church from one era to another: it was McLuhan’s intent to distinguish between the truth of Christian individualism and the new “myth” of participatory Christianity, which is revealed instantaneously at “high speeds” in the electric age.[34] McLuhan could confidently predict that we are living in the “most religious” age ever precisely because the universal dissemination of the Christian message had become far more transformational than old, discredited notions like individualism.

The Right Side of History—Kojève or McLuhan?

There is remarkable agreement between Kojève and McLuhan on the unification of humanity in our time as well as the Christian roots of this process, even if they profoundly disagree over the status of Christianity as “myth.” They agree that Christianity is the one truly universal religion, one that best fits the liberal modern age. They even agree that this process is finally becoming intelligible to human beings long after it has been advancing for the past 150 years or so. The main difference is this. Whereas Kojève contends that the universal homogeneous state leaves Christianity behind as obsolete and myth-eaten. McLuhan argues that the new electric age of the global village breathes new life into this myth and even fulfills the medieval dream of unity. McLuhan sees post-atheist Christians where Kojève only spies post-Christian atheists.

There is an even more radical implication to McLuhan’s thought that sets him apart from Kojève. History is far from over, at least in a post-religious sense, precisely because religious myth is still with us. In fact, we have no choice but to think in mythical terms. While electric media would breathe new life into religious myth, the latter would celebrate the global unity ushered in by this technology. McLuhan may even avoid a powerful objection from Leo Strauss to the historicism that Kojève defended. This objection is: how do we know that we are in the final stage of History, that this proclamation of its End is not another stage in the dialectic? Strauss writes in Natural Right and History: “Every doctrine, however seemingly final, will be superseded sooner or later by another doctrine.”[35] McLuhan’s answer is that we do not know the final direction of History at all. The rear-view mirror focuses on the past or the ever-changing present, not the future. McLuhan’s eschatology is far more fluid than Kojève’s Marxist blueprint.

A Voegelinian Conclusion

Still, one pressing question remains. Why do we need religion to make sense of the changes brought on by electric media? The answer is that only a religious mind can understand the paradox of hope amidst apocalypse. Whereas Kojève’s End of History might, following Nietzsche, bring about the boring existence of “last men” who equated happiness with material contentment,[36] McLuhan thought that the alliance of electric technology with the messianic dream of unity might be explosive. Despite his occasional optimism, McLuhan was not predicting in Pollyannaish fashion that the electric age would bring about heaven on earth. By the end of the 1960s, McLuhan starkly warned that the new age of tribalism, which put an end to the bourgeois individualism of the print age, would impose a stern morality on its members and that marriage and the family in particular would become “inviolate institutions” while infidelity and divorce would “constitute serious violations of the social bond, not a private deviation but a collective insult and loss of face to the entire tribe.”[37] Privacy would be no more. Furthermore, the whole process of change would be a violent one, in which nation-states would disintegrate into tribalist enclaves while peoples search for new identities in a violent global theatre of the absurd: “as men not only in the U.S. but throughout the world are united into a single tribe, they will forge a diversity of viable decentralized political and social institutions.”[38]

Within this new global consciousness, the old medieval dream of global unity may still happen. “In a Christian sense, this is merely a new interpretation of the mystical body of Christ; and Christ, after all, is the ultimate extension of man.”[39] Although humanity may build a New Jerusalem of unity amidst disunity, the opposite may also be a distinct possibility: “There are grounds for both optimism and pessimism. The extensions of man’s consciousness induced by the electric media could conceivably usher in the millennium, but it also holds the potential for realizing the Anti-Christ—Yeats’ rough beast, its hour come round at last, slouching toward Bethlehem to be born.”[40]

McLuhan’s Christian preoccupation with the resurgence of tribalism is unsurprising. In fact, his various reflections perhaps illustrate Eric Voegelin’s trenchant observation, in From Enlightenment to Revolution, that tribalism “exhales a bad odor in a civilization which is still permeated by traditions of Christian universalism.”[41] McLuhan, after all, thought that tribalism demonstrated that the world was already living through an apocalypse.[42] Even when he sounded optimistic that Christianity alone can transform identity or that the “poetry” of God, “incarnating and uttering the world,” can withstand all these changes, McLuhan never abandoned his prediction on the inevitability of the conflict between individualists and tribalists. This pessimism is absent in Kojève, who was convinced that most human beings would become rational atheists (or Left-Hegelians) in the last stage of History. This last point illustrates another insight of Voegelin’s. He writes:

“The difficulty of distinguishing between tribalism and universalism, which is serious even in the case of the Communist idea, is practically unsurmountable for a progressive intellectual (who himself belongs to the masse) when the tribe is co-extensive with mankind at any given point of time.”[43]

The parochialism that Voegelin spies in the progressivist mind applies in spades to Kojève, who rarely considered the possibility that History might not be on the side of Left-Hegelianism.[44] Aren’t Left-Hegelians just another tribe, restricted to the modern West?)

Yet McLuhan at least knew that the old tribalism had never disappeared from history. Moreover, tribalism was Janus-faced. Tribalists could just as unwittingly unify the world as destroy it with the same technology. This paradox was more intelligible to the Christian mind. The incarnation of Christ through technological means would be equally violent and liberating, particularly if not all citizens of the global village were Christian, much less religious. The egalitarian spirit of Christianity may repel and provoke the forces of tribalism, even if the church itself takes on tribalist forms. Despite the occasional triumphalism of McLuhan, it is hard to deny the accuracy of his insight into the conflict between religious universalism and tribalist particularism. Unlike the certainty with which Kojève made his pronouncements, McLuhan cautiously hoped. Faith, after all, is the opposite of certainty.[45]

While religion has experienced a powerful revival on a global scale since the death of Kojève in 1968, western democratic elites have still held onto the secular myth that most human beings desire progress and, with it, rational atheism. This lingering version of history may be the most powerful superstition of our time, although it does not enjoy the influence of religious myth in our age. Tribalism reminds us that human beings have not meekly become self-interested consumers around the world. Even if democracy is the wave of the future, there is no reason to think it has to be bourgeois and individualistic. Not only then is myth still relevant. It is also an indispensable way of comprehending our present age.

Notes

[1] Robert Nisbet, History of the Idea of Progress (Basic Books: New York, 1980), 171-316.

[2] Marshall McLuhan, “Playboy Interview: ‘Marshall McLuhan—A Candid Conversation with the High Priest of Popcult and Metaphysician of Media,” in Essential McLuhan, edited by Eric McLuhan and Frank Zingrone (Toronto: House of Anansi Press, 1995), 238. This interview occurred in 1969.

[3] I draw this connection between Hegel and McLuhan in my “A Christian Hegel in Canada,” Modern Age 61 (Winter 2019), 57. This essay is also available at https://isi.org/modern-age/a-christian-hegel-in-canada/.

[4] Francis Fukuyama, The End of History and the Last Man (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1992).

[5] See Andrew Levine, In Bad Faith: What’s Wrong with the Opium of the People (Amherst, NY: Prometheus Books, 2011).

[6] Alexandre Kojève, Introduction to the Reading of Hegel, translated by James H. Nichols, Jr., and edited by Allan Bloom (New York: Basic Books, 1969), 161n. The original text in French is Introduction à la lecture de Hegel (Paris: Gallimard, 1947), 436n. I cite the original text and translation where appropriate, given the fact that the English translation seriously abridges the lectures of Kojève.

[7] Alexandre Kojève, “Capitalisme et socialisme: Marx est Dieu, Ford est son prophète,” Commentaire 9 (Spring 1980), 136.

[8] Kojève, Introduction à la lecture de Hegel, 200 and 255. See also Barry Cooper, The End of History: An Essay on Modern Hegelianism (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1984), 192.

[9] See Havers, “Christian Hegel,” 52. See also H. S. Harris, “From Hegel to Marx via Heidegger,” Philosophy of the Social Sciences 13 (1983), 247-51.

[10] Alexandre Kojève “Hegel, Marx, and Christianity,” Interpretation 1 (1970), 25-6.

[11] Cooper, End of History, 242.

[12] Kojève, Introduction to the Reading of Hegel, 57.

[13] Kojève, Introduction à la lecture de Hegel, 535-38.

[14] Kojève, Introduction à la lecture de Hegel, 284-85.

[15] See Cooper, End of History, 189 and 229; Harris, “From Hegel to Marx via Heidegger,” 250.

[16] Alexandre Kojève, “Review of Two Books by G. Fessard,” Interpretation 19, no. 2 (Winter 1991-1992), 191. (emphasis original)

[17] Havers, “Christian Hegel,” 56-9.

[18] John Fekete, “McLuhanacy: Counterrevolution in Cultural Theory,” Telos 15 (1973), 79.

[19] See Marshall McLuhan, The Gutenberg Galaxy: The Making of Typographic Man (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1962).

[20] Yoram Hazony, The Virtue of Nationalism (New York: Basic Books, 2018), 68.

[21] Marshall McLuhan, Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man, with a new introduction by Lewis Lapham (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1994), 38-39.

[22] Ibid. 347.

[23] See H. S. Harris, Hegel’s Ladder, vol. one: The Pilgrimage of Reason (Indianapolis: Hackett, 1997), 298: “We have to understand the ‘inverted world’ as a world of reactive law. The ‘resting law’ can only be inverted into a dialectical unity of opposites. In this way the initial ‘pure thought’ is developed into a concept by being united with its own complement or opposite.” See also Cooper, End of History, 85-8.

[24] McLuhan, “Electric Consciousness and the Church,” in Marshall McLuhan, The Medium and the Light: Reflections on Religion, edited by Eric McLuhan and Jacek Szlarek (Toronto: Stoddart, 1999), 84.

[25] McLuhan, “Electric Consciousness and the Church,” 83. See also “Playboy Interview,” 249.

[26] McLuhan, “Electric Consciousness and the Church,” 84.

[27] McLuhan, “Electric Consciousness and the Church,” 88.

[28] McLuhan, “’A Peculiar War To Fight’: Letter to Robert J. Leuver, C.M.F.,” in The Medium and the Light, 91-92. This letter is dated July 30, 1969.

[29] McLuhan, “Religion and Youth: Second Conversation with Pierre Babin,” in The Medium and the Light, 104. McLuhan gave this interview in 1977. In Understanding Media, McLuhan similarly rejects a “linear” interpretation of the Bible in favor of one that recognizes the relation between God and the world as well as that between man and his neighbor in terms of relations that “subsist together, and act and react upon one another at the same time.” (25-6)

[30] McLuhan, “Catholic Humanism and Modern Letters,” in The Medium and the Light, 157.

[31] McLuhan, Understanding Media, 47.

[32] McLuhan, Understanding Media, 61.

[33] Quoted in Eric McLuhan, “Introduction,” in The Medium and the Light, xxvii. The quote is from a letter to Allen Maruyama (December 31, 1971).

[34] McLuhan, “Electric Consciousness and the Church,” 86. Here he remarks that the “Christian myth is not fiction but something more than ordinarily real.”

[35] Leo Strauss, Natural Right and History (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1953), 21. See also John Adams Wettergreen, Jr., “Is Snobbery A Formal Value? Considering Life At The End of Modernity,” The Western Political Quarterly 26, no. 1 (March 1973): 111.

[36] Cooper, End of History, 334. Cooper also notes that another type of human being might emerge, namely “men of power who know there are no limits, no rules, because they know themselves free to make up their own.” (334) In short, Nietzschean supermen might exist uneasily alongside the “last men.”

[37] McLuhan, “Playboy Interview,” 253.

[38] McLuhan, “Playboy Interview,” 258. In the same interview, McLuhan refers to the “Balkanization of the United States.” (257)

[39] McLuhan, “Playboy Interview,” 262.

[40] McLuhan, “Playboy Interview,” 268.

[41] Eric Voegelin, From Enlightenment to Revolution, edited by John H. Hallowell (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1975), 97. It is noteworthy that McLuhan was interested in Voegelin’s work on Gnosticism. See Barry Cooper, Consciousness and Politics: From Analysis to Meditation in the Late Work of Eric Voegelin (South Bend, IN: St. Augustine’s Press, 2018), 90.

[42] McLuhan, “The De-Romanization of the American Catholic Church,” in The Medium and the Light, 56.

[43] Voegelin, From Enlightenment to Revolution, 98.

[44] At times Kojève considered this possibility. See his “Hegel, Marx, and Christianity,” Interpretation: A Journal of Political Philosophy 1 (Summer 1970), 41: “The most one can assert is that it (History) has not decided between the ‘leftist’ and the ‘rightist’ interpretations of Hegelian philosophy. For today the discussion still continues.”

[45] Cf. Eric Voegelin, The New Science of Politics: An Introduction (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1952), 122: “Uncertainty is the very essence of Christianity.”

The author presented a version of this paper at the 39th Annual Meeting of the Semiotic Society of America in Seattle in 2014.