Being the Last Man on Earth: I Am Legend and the Age of Social Distancing

Who knew the end of the world would be so boring? Far from the fleeing for our lives we were promised, Covid-19 has instead confronted us with an unyielding assault of monotony. The fire and brimstone we anticipated has been replaced by Netflix and more Netflix. In sum, much as Nietzsche or C.S. Lewis might have predicted, the collapse of civilization has been not one of prodigious freefall but a prosaic, unremarkable descent into sameness. The imagination struggles to find purchase in comprehending what is transpiring around us: this simply is not the Armageddon we expected. Instead, we find ourselves trapped in a doomsday scenario which, perhaps more so than our lives, has struck at those invisible bonds between humans called community. Looking at the story of I am Legend may help us to understand our situation. And looking at it twice even more so.

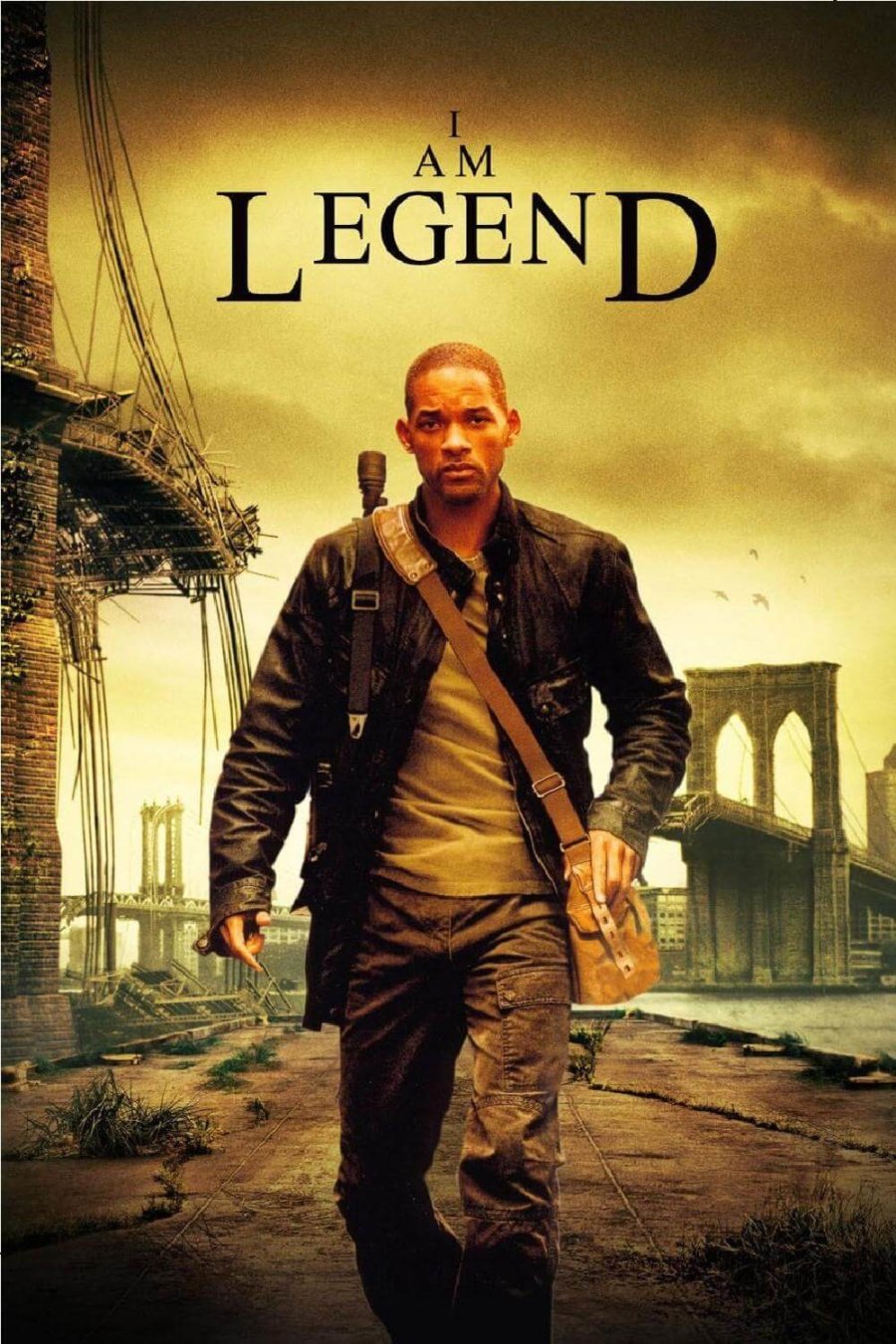

As a model for encountering the trials of isolation, the image of Will Smith teeing off of an aircraft carrier into New York City seems apropos. In I am Legend (2007), Smith’s Robert Neville seems to have somewhat of a romantic experience as the last man on earth. After a cure for cancer mutates into an airborne pathogen, 90% of humanity expires quickly and the remainder become zombie vampires. We find Neville—seemingly the only one immune to the virus—and his German Shepherd Sam roaming the deserted streets of Manhattan, breaking up the banality of systematically gathering supplies by hunting for deer in Times Square. Confined to his house in after dusk for fear of the horde, he passes his evenings with movies and medical experiments, searching for a cure. In sum, he looks like an exemplar for our time in quarantine: maintaining a schedule, productive, and generally put together. At the very least, he wears pants every day. But, as usual, we have discovered over the past several weeks that Hollywood dressed things up. We now see that Smith’s clean-cut appearance and tidy house may be the least realistic part of the movie about vampires.[i] Nonetheless, confined to our homes for fear of human contact, we can appreciate something of Neville’s situation.

The novel on which the movie is based tells a somewhat different tale. Richard Matheson’s I am Legend (1954) shows us Robert Neville without Smith’s suave mien and appearance. Here we encounter the protagonist not three years into his exile from civilization but only a few months. Much like most of America presently, this version of Neville is a mess. He is depicted as a hard-drinking procrastinator, prone to bouts of depression, who cannot seem to muster the inertia to begin home repairs. This Neville’s activities are anything but systematic. He responds to immediate biological needs without thought of the next day. He does not quite live in the moment, however. His drinking connects him with his past and strands him there. Unable to make peace with what he has lost, he simply abides in the land of self-pity. The reader cannot fail to sympathize with a man who has had to bury his wife, twice. No dressing things up here.

The difference between these two Nevilles is one part characterization. Even before the outbreak, Smith’s Neville is a US Army virologist, accounting for both his physique and his knowledge of biology. The Neville of the book was a factory laborer. The movie Neville also enjoys the advantage of canine companionship; he discourses with Sam as though the latter could reply, and he enjoys the company of a creature who bears some marks of understanding. Compared with Tom Hanks’ volleyball in Castaway, we ought not underestimate the significance of a dog’s simple head tilt. The dog which the Neville of the book discovers makes only the briefest of appearances, before succumbing to injuries. Perhaps like ourselves, the literary Neville was not built with quarantine in mind.

The difference is also in the timeline of the stories. By beginning three years after the outbreak, the movie skips the important part by bypassing the protagonist’s character development. The Neville of the novel begins with nothing besides a somewhat-fortified house and an acute drinking problem. Like many of us, Matheson’s Neville does not have order in his life. He imposes order upon it, by degrees. That is the drama of the story. His investigation into the virus begins a few months into his isolation when he, as an amateur, ventures to the local library to obtain few books on biology. Three years after the initial outbreak, we find him an efficient, systematic scavenger who is collecting resources by day and researching the cure by night, just as he was in the movie. As Neville reflects, “A man could get used to anything if he had to.”[ii] But the movie skips over the cultivation of habit amidst isolation. It simply wills them into being.

Yet the book shows us just how much of a struggle this development is. This cultivation of habit takes time, especially since humans are prone to cultivate the wrong habits from time to time. When we meet Smith’s Neville, he is a completed character. He has already had three years to adapt to his environment. But the Neville of the book reverses his steady descent into self-destructive malaise only by degrees. Only after years does he establish systems for foraging and routines for his days. Only after years of struggle does he kick the bottle. But all of this is heavily dependent on him coming to terms with his situation.

To the list of differences we should also add the distance between the two versions of the story in the depiction of Aristotle’s observation regarding politics: Man is by nature a political animal. Any man without a city is either a beast or a god.[iii] Without community, the Neville of the books becomes a beast. His drunken lethargy bespeaks the triumph of his animal instincts over his reason. But he gradually adapts, using reason to overcome despair. He cannot, however, overcome the absence of community. Neville displays a fundamental, social autism when confronted with another human for the first time in years. How could he not? An ordered life alone does not raise him from the level of beast to human.

Community, too, is something of a habit, and an important one at that. Here the book’s depiction of this deprivation of an essential human need rings more honest. Smith’s Neville limps along by communicating with his dog and with trips to the movie rental store—perhaps another jarringly unrealistic dimension of this tale of vampires—which he has populated with mannequins whom he imbues with particular personalities. This suture allows him to play pretend at living in community so that, when he discovers other humans amongst the ruins, he very quickly reacclimates himself. But this, again, is Tinsel Town magic. The Neville of the book, by contrast, loses himself in self-pity before closing himself to his humanity: “Rather than go on suffering, he had learned to stultify himself to introspection. Time had lost its multi-dimensional scope. There was only the present for Robert Neville; a present based on day-to-day survival marked by neither heights of joy nor depths of despair. I am predominantly vegetable, he often thought to himself. That was the way he wanted it.”[iv] This Neville has amputated a part of himself. He does not know how to converse with the woman he encounters three years into the collapse, using “the harsh, sterile voice of a man who had lost all touch with humanity.”[v] He mistreats her with the cold detachment of a scientist at study rather than a human being encountering another. Although perhaps vindicated in his suspicion by the plot, such consequential thinking overlooks the fundamental premise: this man is crippled in his capacity to have and be a part of a community. In his isolation, he has lost something essential to his humanity which he cannot recover. We should be mindful that Neville’s aforementioned observation cuts both ways: “A man could get used to anything if he had to.”[vi]

Hopefully we will not have years adapt to this new way of life. Hopefully we will not have months. But we can learn from this tale of the last man on earth the importance of habit and particularly the habit of community, a habit not unlike in importance to breathing within the complex creature known as man. The current crisis challenges us to maintain order in isolation rather than give way to despair. And that order, while largely manifested externally in practices like schedules and moderation, also extends internally to the needs of the soul. Even though we have lost our capacity to fully participate in community, maintaining the trappings of it may do for a time. Still, as we evaluate what is considered “essential” in considering what to re-open and how soon, let us not mistake man for merely an animal with merely animal needs. Unlike the Neville of the movie, most of us are not custom built for quarantine. We need to adapt to it. But, at the same time, we need also to be aware of how much we adapt to it.

Notes

[i] I am Legend, directed by Francis Lawrence (Burbank, CA: Warner Bros. Pictures, 2007).

[ii] Richard Matheson, “I am Legend” in I am Legend and Other Stories (New York: Tom Doherty Associates, LLC, 1995): 16.

[iii] Aristotle, Aristotle’s Politics, trans. Carnes Lord, 2nd ed. (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2013): 1253a.

[iv] Matheson, Legend, 160.

[v] Ibid, 166.

[vi] Ibid, 16.