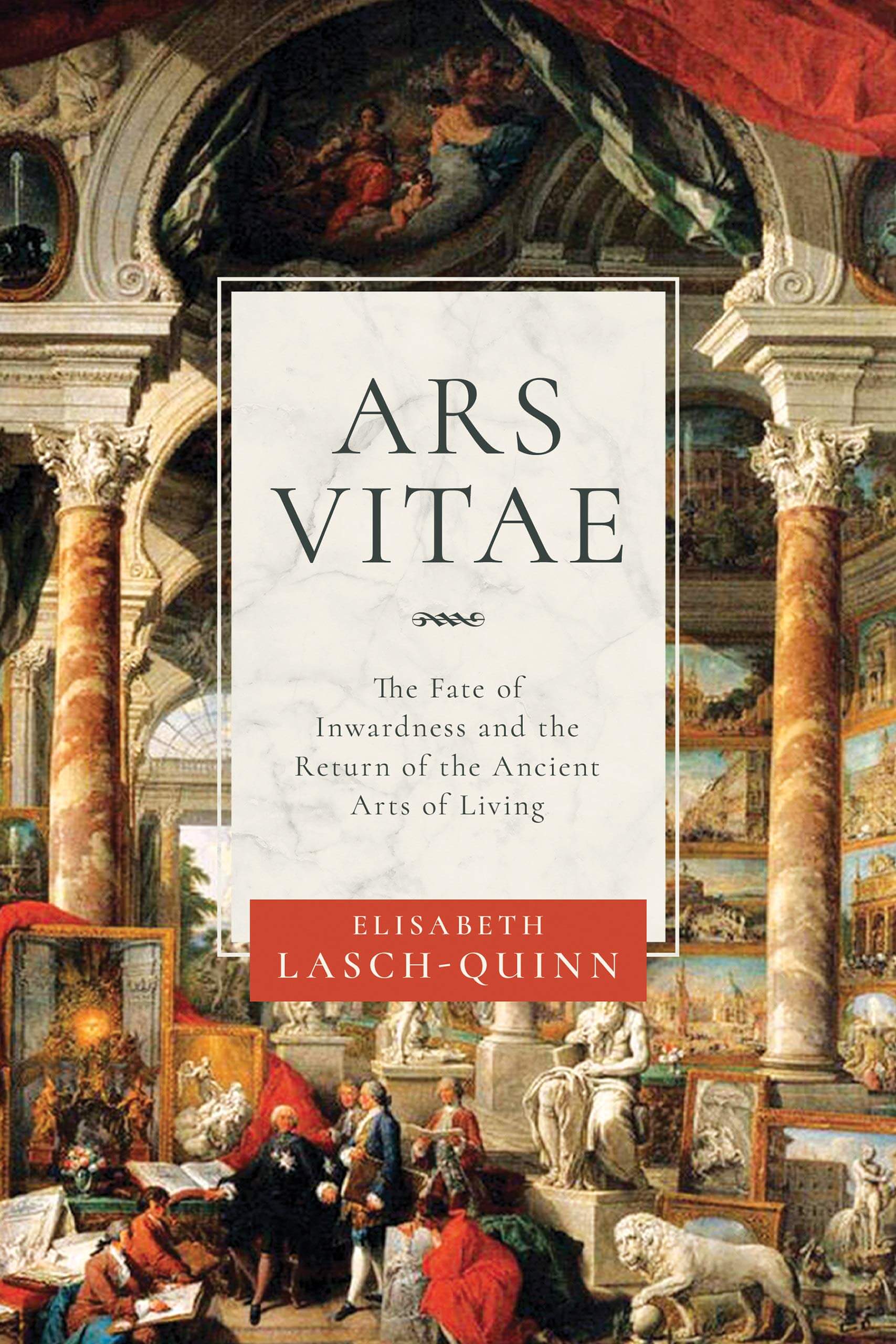

Is There Hope in Reviving Ancient Virtues? Elisabeth Lasch-Quinn’s “Ars Vitae”

Elisabeth Lasch-Quinn. Ars Vitae: The Fate of Inwardness and the Return of the Ancient Arts of Living. Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press, 2020.

Ars Vitae opens with two observations about contemporary American life: many people are searching without success for guidance that works about how to live, and many films, books, websites, works of architecture, and other cultural projects are reviving interest in and seeking inspiration from ancient Greco-Roman philosophy. Exploring the potential of this latter phenomenon to be important for the former is the task of the text. Elisabeth Lasch-Quinn joins a number of scholars who contend that Americans are drowning in a culture of the therapeutic which fixates on the self, expects others to be manipulatable observers who pour out moral non-judgmentalism in response to confessions, and encourages individuals to think about means, mechanisms, and marketable solutions without considering meaning, moral goods, or ends. In short, Lasch-Quinn thinks the therapeutic causes a “loss of inwardness” (18). She depicts this mainstream worldview as a kind of new Gnosticism and fourth Sophistic, complete with paid experts whose knowingness precludes any real learning or listening. And she pitches her book as an opportunity to evaluate four Greco-Roman schools of thought as possible alternatives to the therapeutic, through studying ancient texts and their contemporary offspring. Lasch-Quinn’s analysis is not a wholesale rejection of seeking personal healing through conversation or an unqualified promotion of all things Greco-Roman in contemporary culture. Rather, Ars Vitae explores ancient and present-day Gnosticism, Stoicism, Epicureanism, Cynicism, and Platonism in order to determine whether or not any of the latter four offers a path out of the therapeutic, capable of helping us cultivate an inner life.

The text consists of an introduction, chapters dedicated to new Gnosticism, Stoicism, Epicureanism, Cynicism, and Platonism, a conclusion, and an epilogue. Each body chapter begins with one or two films of the last couple decades and then turns to examine the ancient school itself. The chapters then jump forward to present times to give attention to a larger, but still focused and intentionally chosen, set of contemporary works and to compare the philosophies of living embodied in these cultural projects to the ancient schools themselves. Lasch-Quinn concludes each body chapter with reflections on how these Greco-Roman philosophies relate to the therapeutic and how they might be poorly or well-suited to assist seekers in their quest for a meaningful life.

Lasch-Quinn begins with New Gnosticism, not because it is a candidate in the search for a sustaining art of living but because she contends that it is a major contributor to the culture of the therapeutic and exists as a kind of backdrop against which the other schools are emerging. The Da Vinci Code and The Matrix open the chapter, and Lasch-Quinn draws the reader to see how the idea that the apparent world is an intricate illusion hiding a darker, deeper reality is central to the plot of both films. Noting that scholars disagree about the historical emergence, unity, and nature of Gnosticism, Lasch-Quinn gives a concise overview of the ancient movement and its fundamental tenets, emphasizing its conviction that behind the material world with its evil origins lies a spiritual world, knowledge of which saves the select few that are capable of attaining it. She then engages with Voegelin’s analysis of modern Gnosticism, sharing his belief that the recognition of human limitations, a consideration of ends, and a concern for the greatest or highest good are crucially absent from the philosophy. Lasch-Quinn examines several contemporary apologists of Gnosticism, some of whom see it as an alternative kind of Christianity that empowers the individual over institutions, eliminating exterior gods and recognizing the “inner light” or “divine spark” within human beings (64-66). Other self-proclaimed Gnostics call on their readers to “Wake up!” from the illusion in which they are living and promise to open their eyes to how evil the world truly is (76-77). Lasch-Quinn characterizes interests in cryogenic preservation, AI dominated civilizations, and architectural trends like the postindustrial sublime as parts of new Gnosticism while judging theories like the “Gaia hypothesis” as not properly Gnostic and attempts to align a preference for the cosmic feminine with a disdain for embodiment as inconsistent (80). Ultimately, Lasch-Quinn sees in Gnosticism a withdrawal from material reality, a rejection of any criteria that might judge or rank ways of living, and an abandonment of the search for meaning. In these ways, New Gnosticism advances, but does not encompass, the therapeutic.

Lasch-Quinn’s analysis of New Stoicism begins with scenes from the film Gladiator which depict its hero, Maximus, as almost unphased by utter betrayal, debasing slavery, and intense physical pain. She notes that many thinkers conceive of the current American malady as a problem in handling emotion and as a result see Stoicism as the needed cure of the day. She then turns to examine ancient Stoicism, introducing the reader to Zeno and Chrysippus among others and emphasizing a shared desire among the Stoics to achieve freedom from emotions and indifference to non-moral goods. Lasch-Quinn lingers longer on Marcus Aurelius, exploring how to harmonize, or merely hold at the same time, the belief that life is short, fleeting, and tiny from the perspective of infinite time with the belief that leading a life of virtue in accordance with nature matters. Setting aside this puzzle, she then examines contemporary advocates of Stoicism who see it as the antidote to today’s unhealthy preoccupation with power, material possessions, and fame as well as contemporary tendencies to sever ethics from natural science and logic. Lasch-Quinn notes disagreements among present-day Stoics, examining a proponent of the ancient school who thinks many others have lost sight of the Greco-Roman Stoics’ concern for the good and reduced the philosophy of action to one of fixating on identity and reasoning solely about one’s agency and means. Not always tethered to a concern for virtue, New Stoicism surfaces as capable of being a philosophy compatible with the modern therapeutic in some cases and an unreflective, knee-jerk appraisal of heartlessness in others. In the end, Lasch-Quinn leaves the reader thinking that even ancient Stoicism – with its concern for the good, focus on action, and more nuanced treatment of the human psyche – may be fatally flawed and incapable of providing a robust alternative to the therapeutic. She quotes Seneca allowing a place for some amount of grief and suggests that such an acknowledgement of the place of emotion in human life is incoherent in a text that advises its reader to overcome emotion. “[W]e are truly creatures of emotion,” Lasch-Quinn writes, and a school of thought that seeks eudaimonia through becoming indifferent to emotions eliminates what are “our very ticket to the experience of transcendence and immanence alike” (142-143).

Eat Pray Love opens the account of New Epicureanism; its high appraisal of gustatorial and travel experiences makes it a textbook artifact of contemporary Epicureanism. Turning to Epicurus himself, Lasch-Quinn places his teachings on pleasure within the broader context of his beliefs about the physical world and celestial beings, introducing readers to his depiction of atoms, the void, material souls, and gods who do not intervene in the unblissful troubles of human existence. Studying these matters was, for Epicurus, part of pursuing a life of pleasure, since he understood pleasure to be the “absence of pain in the body and of trouble in the soul” and posited that incorrect ideas about the universe and the gods could lead to anxiety (160). To be Epicurean, in the ancient sense, then does not mean pursuing any pleasure full-stop – doing so would introduce tumults or unease in the soul. Rather it consists of acting with virtue for the sake of peace, accepting death as the end of the soul’s existence, and pursuing a life free of tumults and troubles – not letting emotion overrule reason and not getting involved in politics or falling in love, among other things. Lasch-Quinn begins exploring contemporary interest in Epicureanism with Stephen Greenblatt’s suspenseful account of the discovery of Lucretius’s De Rerum Natura. In Greenblatt’s eyes, Lucretius’s text presents a “whole new worldview” that departed from the dogmatism that preceded it and launched modernity, beginning with the renaissance (166). Lasch-Quinn raises doubts about several of Greenblatt’s claims, arguing that modernity contains conflicting worldviews and illustrating with a detailed reading of Botticelli’s Primavera that some works of renaissance humanism come to greater life when understood as Neoplatonist pieces. Lasch-Quinn then examines Martin Jay’s study of experience which uses an exploration of the two words for experience in German to help explain why the pursuit of intense “prereflective experience[s]” are on the rise while experiences having the “narrative coherence of a meaningful journey over time” seem to be becoming rarer (177). Lasch-Quinn notes that the contemporary “cult of experience” (in the first sense of the word), like the therapeutic, can entail exploration and self-discovery without deeper meaning (176). And she characterizes the protagonist’s journey in Eat Pray Love along these lines, drawing the reader’s attention to the film’s individualist focus and lack of attention to deeper yearnings in the end. While the latter is foreign to ancient Epicureanism, Lasch-Quinn notes that withdrawing from commitments to the community and understanding friendship as instrumental are facets, not instances of departure from, the ancient school of thought. Epicureanism, new or old, may leave seekers hungry for meaning because it focuses too much on the individual and lacks a belief in the transcendent good.

Lasch-Quinn begins her discussion of Cynicism with a brutal scene from the film 300 and a qualifying note that Cynicism was not a formal Greco-Roman school of thought and does not constitute philosophy according to some scholars. In any case, the sayings of Cynics uncontestably form a movement, and Lasch-Quinn recounts stories of Diogenes of Sinope damaging state coins, living in a tub, and attending to all matters of the body in public that provide the context in which the movement’s famed founder purportedly professed the need to abandon convention and distractions in order to live a simple life guided by nature and animated by virtue. Diogenes called for the harmonization of a person’s beliefs and actions, and Lasch-Quinn’s account calls on readers to consider whether Diogenes and contemporary cynics are exemplars of this kind of harmony or merely shameless criticizers, engaged in playing the role of the person who deconstructs roles. Moving towards modernity, Lasch-Quinn notes the prevalence and variety of forms of cynicism in the current intellectual culture: having “radical honesty,” employing a “hermeneutics of suspicion,” and being the “debunker” or ironic reader, to name a few (217). Observing doubts among thinkers about the value of the idea of experience, she surveys several stances, presenting Walter Benjamin’s pursuit of more mystical, magical, pre-modern experiences, Richard Rorty’s rejection of experience as a reliable epistemological tool, and Foucault’s insistence that experience is constructed and simultaneous call for certain extreme experiences that mix pain with intense pleasures in an attempt to annihilate the self. Lasch-Quinn shares MacIntyre’s observation that current discussions of experience lack a “moral vocabulary,” and returns to the film 300, arguing that its failure to interpret, judge, or ascribe meaning to its graphic display of brutality makes it an example of the nihilism and “ironic detachment” of contemporary cynicism (223, 228). Lasch-Quinn observes how this same disposition courses through “deathworks” like Robert Mapplethorpe’s Self-Portrait, which support Phillip Reiff’s assertion that “transgression has now replaced creation as a cultural ideal” (230-231). She then presents a reading of Peter Sloterdijk’s criticism of the conception of the self within modern cynicism and subsequent summons for a revival of ancient Cynicism before conducting a lengthier exploration of Foucault’s final lecture course. Lasch-Quinn’s analysis raises the possibility that Foucault’s art of living – or John Sellar’s articulation of it – is just another instance of the contemporary fixation on lifestyle, since it seems to view both logos and bios as constructed fictions. Additionally, his articulation of the art of living lacks a moral dimension that is arguably essential. Lasch-Quinn finds and explores this moral dimension in Foucault’s interlocutor Pierre Hadot before she deems both contemporary and ancient Cynicism wanting for their lack of consideration of ends.

Interstellar opens the final body chapter; Lasch-Quinn emphasizes the film’s depiction of the universe as enchanting and portrait of love as capable of overcoming all human flaws and constraints of material existence. She gives a brief account of Plato’s life, a description of the Academy and its unique practices and shared beliefs, and a short sketch of revivals and reinterpretations of Plato’s work. She presents Plato’s account of love in the Symposium, contrasting the beautiful, virtue-inspiring revelation in Diotima’s speech with the unveiling of the dark sides of reality in the Gnostic tradition. Turning to consider Plotinus, Lasch-Quinn finds his regard for unity, emphasis on the inner life, and belief in the good countercultural and sees his thought as a potential antidote to today’s “atomic individualism,” suffering, and therapeutic culture (288). But she also argues that, in the search for a practical philosophy of life, seekers should be thoughtful and discerning. With the help of various scholars, she points out more nuanced differences between Stoicism and Plotinus’s thought, emphasizing how Plotinus sees emotions as aspects of human nature that need to be not removed but rather moved beyond for the sake of insight. Plotinus understands suffering as an inherent part of life, and he gives readers reasons why they should follow his practical advice. Lasch-Quinn also draws distinctions between Plotinus’s thought and the Gnostic tradition, arguing that the two differ in form and content. She notes how the former holds the divine to be fundamentally one, while the latter posits the existence of both good and evil divine forces. Moreover, while Gnostics exhibit a kind of pride and disdain as a result of their increased understanding, Plotinus argues that having greater visions of the truth should only increase how beautiful the material world appears to someone. The tenth book of Augustine’s Confessions displays this kind of response to the material world; moreover, it presents transcendence not as making a person immune to “loss, longing, and pain,” but as recognizing and speaking to the complexity of all three (307). Lasch-Quinn draws one last comparison of Gnosticism and Neoplatonism – juxtaposing the “sophisticated knowingness” of a YouTuber pointing out every factual inaccuracy in Interstellar with Plotinus’s call for “receptivity and a special mode of listening” – before returning to Interstellar itself (313-314). She does not answer the YouTube critic with unqualified praise of the film – Ars Vitae, as a whole, summons readers to think deeply about and judge cultural works of the day for themselves. But she does maintain that Interstellar is one film that might inspire us with “Platonic wonder” and a sense that life is much more “interdependent” and “mysterious” than an individualistic mindset or attitude of “knowingness” might let us see (320). Along with Plotinus’s Enneads, Interstellar might help us realize that mere rules and practices are apt to wither without visions of beauty experienced in acts of love and contemplation. Lasch-Quinn ends the chapter with a call for “living from within” – abandoning appearances, looking at the self from inside, and experiencing the beauty that comes from inner growth – and briefly gazes at love in Martin Luther King, Jr., Van Morrison, and Bernstein’s works (322, original italics).

Lasch-Quinn concludes the book with some final reflections on the art of living and Platonism’s suitedness as a guide for learning this art. She argues against the idea of instrumentalizing philosophy or seeing it as a means to obtain ends like power and wealth. And she contends that an art of living must take other individuals and the community into consideration in a meaningful way – self-help that involves attending only to oneself is bound to fail. The art of living, in Lasch-Quinn’s account, is in many ways an art or life of learning, and she calls for openness and humility, both being sensible and honest responses to the lack of knowledge human beings have about fundamental questions and their ramifications for daily life. Lasch-Quinn briefly explores new Aristotelianism, distinguishing its assertion of the alignment between the good of the individual and the good of the community from enlightened self-interest. However, she ultimately finds the philosophy inferior to Platonism because of its focus on one means – virtuous habits – and one end – eudaimonia. Lasch-Quinn sees Platonism as a school of thought that investigates and reflects on ends, that calls for on-going thinking about goods, and that even directs us to pursue not only a good life but a beautiful one.

An epilogue follows the text and compares the separateness between two people that allows them to give and receive each other’s love as a gift to the separateness between knowledge and those in search of it, arguing that the very distance that precludes possessing knowledge enables love of it. Lasch-Quinn sees this separateness in the film Once, in which the distance two lovers keep between themselves is the very thing that enables them to transform their “pain into poetry” (355). And she calls on readers to grow in openness, to listen, and to foster an inner life that will be like a well to which they can always return. Her final words celebrate human beings as creatures who can encounter, encourage, and live attuned to beauty.

Ars Vitae is a rich text, replete in explorations of cultural works that span across many years and genres. It persuasively presses detailed analyses of these works into the service of supporting larger ideas about the current American moment and the perennial human condition. Readers wanting clear and specific directives will not find what they are seeking – the book is not a manual but instead a glimpse into, and an invitation to join, a conversation about what is good and how to live. It is all the better for being so. In the end, those who take up Ars Vitae may find themselves, as I did, most grateful to Lasch-Quinn for giving them grounds for hope.