Marx’ World View – Conjectures and Aberrations. A Critical Assessment

Karl Marx (1818-1883) was not a philosopher in the Socratic sense of the European tradition of Plato and Aristotle, Augustine and Thomas Aquinas, Kant and Hegel. While Hegel had long been concerned with the philosophical problem of radical skepticism and the question of how to overcome it through rational philosophy and methodological science, the later Marx had been interested in Hegel almost exclusively in the later final form of his philosophy of the absolute spirit, as expressed most recently in his outlines of the philosophy of law. However, Marx later also had philosophical reservations about Hegel’s speculative Science of Logic (1812/16) because of its delicate attempt of abandoning the principle of contradiction. Aristotle had rightly considered this principle to be evident, although it cannot be further argued for, since anyone arguing for it would have to presuppose it. In this respect, Marx followed the anti-Hegelian view of the neo-Aristotelian Adolf Trendelenburg, who had criticized Hegel for this in his Logical Investigations (1840).

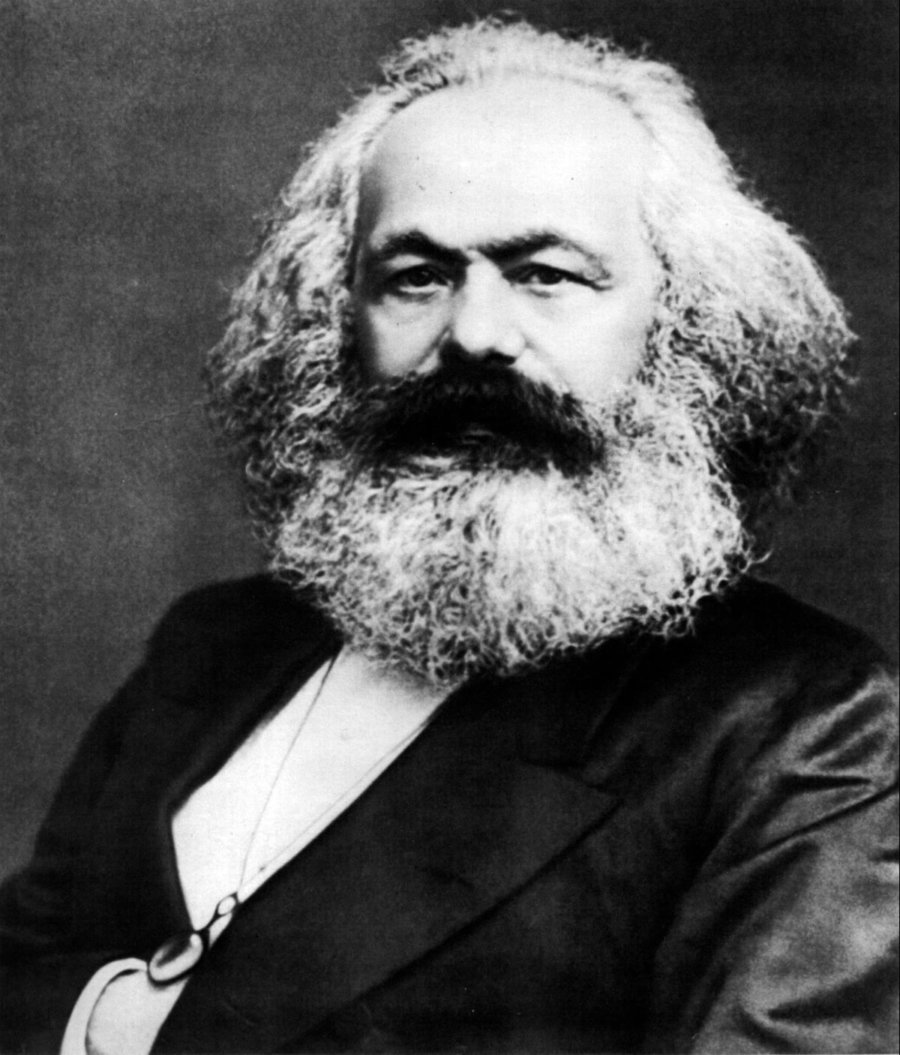

Marx seems to have had little genuine philosophical interest in Hegel’s earlier developmental conception of human consciousness and mind in his Phenomenology of Spirit (1806). Like a socially critical investigative journalist, he was guided more by a hermeneutics of suspicion, and he increasingly thought like a politician only from the end: Cui bono? – Who is benefitting from it? Marx was many things in one: political journalist, committed social critic, philosophizing economist without methodical empiricism and without mathematics, self-appointed protagonist of the labor movement and pseudo-scientific socialist, inventor of the all too simple historical ideology of historical materialism and thus of a myth of historical progress that still has an effect today. But he was never a genuine philosopher who, with methodical skepticism, tested himself and his comrades to see what he himself and others could really know, should do, and could hope to do about all this.

Marx must be understood, studied and evaluated primarily as a political economist in order to do justice to him. For Marx’s three-volume main work Das Kapital (1867-1894) is an economic-political treatise, as its subtitle Critique of Political Economy suggests. But precisely because Marx was not a genuine philosopher who thought with methodological skepticism about the basic problems of theoretical and practical philosophy, that is, about logic and epistemology, ontology and metaphysics, and about ethics, philosophy of law, and political philosophy, he made ideological preconditions about the nature of Man in precisely these problem areas, which are tacitly the basis of his main work. If these premises are wrong or even questionable and problematic, then his main work is built on sand. Therefore, this essay deals primarily with Marx’s world view and conception of man and only secondarily with the ideological heritage of Marxism.

I. Marx Criticism of the Hegelian Philosophy of Law

Hegel’s innovative philosophy of law still breathed the spirit of the French Revolution and civil liberalism, which had represented a cosmopolitan departure from nationalism, from the corporative state and from monarchy. But while Hegel and his students had already been attacked by the restorative forces of the historical school of the legal teacher Friedrich Carl von Savigny and by Catholic Romantics such as Friedrich Schlegel and later Friedrich Wilhelm Joseph Schelling, Marx could only recognize in them an unpopular “bourgeois ideology. In contrast to Ludwig Feuerbach and Heinrich Heine, he no longer defended the new spirit of intellectual transformation, coming from France, of the formerly religiously founded natural law into an egalitarian rational law. Rather, he scented only the suspicion that the new ideas of “freedom, equality, and fraternity” were nothing but a “bourgeois ideology” serving above all the aspiring bourgeoisie, but not the “Third Estate” of wage-dependent workers, peasants without land of their own, day laborers, and slaves.

With his enlightened legal doctrine, Kant wanted to defend the common people, such as workers, peasants, and artisans, in the anti-court spirit of Jean-Jacques Rousseau, by deriving the basic right to dispose of the fruits of their own labor meticulously from basic implications of the practical idea of law. As a former student of theology, Hegel’s basic lines of the philosophy of law largely tied in with the ethical intentions and skeptical method of Kant’s secularized philosophy of law, although he also de-individualized it in order, unlike Kant, to be able to do justice to the community-building spirit of love and the family.

Unlike Kant, Hegel also had a lively interest in the new national economy and studied Adam Smith’s The Wealth of Nations. Hegel’s interest in economics had to do not least with the ethical and political problems of impoverishment in the population, which could hardly be solved by law and the philosophy of law. But Hegel, who never thought merely nationally, but always internationally as well, wanted to overcome Fichte’s isolationalist ideal of a nation that was as self-sufficient as possible.

But a different wind was already blowing from England, triggered by new technological developments and industrialization. This created new problems of mass pauperization of the population and the exploitation of wage-earning workers. It was the technical invention of mechanical looms and mills, steam engines and railroads that, from the middle of the 19th century onwards, led to an unprecedented level of unemployment, especially in the industrialized cities. This increased the dependence of wage-earning workers on the new factory owners, who had legally protected ownership of the new technical means of production.

This caused justified resentments not only in Karl Marx, but also among some other, primarily French, early socialists about the civil rights to property, land and buildings, which were laboriously upheld and defended by Kant and Hegel following the secularized natural law. This resentment of the civil rights to property and land was, however, only partially justified because these civil rights were not wrong, insofar as they were only a minimal constitutional protection structure of real property rights. Of course, a new equality of opportunity in education and health care and a fair distribution of goods through taxes, pensions and welfare state benefits could not yet be achieved with the mere right of ownership. But neither Marx nor the early Socialists had recognized that these civil rights were in themselves something generally useful and good when it came to protecting the higher political goals of social peace based on extensive freedom and justice.

But this legal system, protected by the rule of law, cannot be of any use to a person who has no property worth mentioning and who is not allowed to own land that secures his present and future existence. Therefore, it should have been their concern from the outset that all humans in a civil society have as equal a chance as possible, by school education, vocational training and by their lifelong efforts to be able to acquire own property not only at the directly vital, but also at goods, which secure the own existence up to the age, like a home of one’s own, a pension scheme, a health insurance as well as possibly also own property. But Marx and the early socialists lacked this insight, unlike the later social democrats and Kantian socialists like Leonhard Nelson.

II. Marx’ Materialist World View and Materialist Conception of Man

Since Marx was not a methodically skeptical philosopher like Kant or Hegel, he got lost in the daily business of political commitment. Kant and Hegel had still taken up and examined the intellectual heritage of Plato and Aristotle, brought it together and reassessed it, partly preserved and partly renewed it. But Marx saw in Hegel more and more the philosopher of a “bourgeois ideology” and of the “absolute spirit”. For Marx, Hegel seemed to be more interested in the religions, arts, and philosophies than in concrete people in their social relations of work and production. Therefore, Marx sought a new hero and a counter-image to classical Greek philosophy and Christian theology, which had still been formative for Kant and Hegel. The son of a Jewish citizen having converted to Protestantism found his anti-hero in the Greek philosopher Democritus.

Democritus (ca. 460-370 B.C.) was a pre-Socratic materialist who, like all pre-Socratics, speculated on what man and the world were ultimately made of. But unlike most of the pre-Socratics, Democritus believed neither in gods nor in a reasonable world spirit nor in some basic elements, such as fire, water, earth and air, of which everything in the world is said to be composed of. For him, man and the whole world ultimately consist only of the smallest material particles, which move in empty space and which cause by their movements the changes in things we observe.

Democritus served Marx as an anti-hero of the then new materialist way of thinking, which had been fired above all by the naturalist understanding of nature since Charles Darwin. Without any intelligent God, not only the whole spatio-temporal universe, but also life on earth is supposed to have come into being by itself. Only chance and the laws of nature are said to have been at work when the first primitive forms of organic life appeared. At first unicellular organisms and worms, then fish and reptiles, then mammals and birds, and finally primates and humans, developed from the smallest particles of inorganic matter.

But chance and the laws of nature are not themselves natural forces at work, for they are not substances in space and time with some causal potential. They only belong to the conditions of what happens and of what can happen. Moreover, the mere cosmological assumptions of the existence of space and time as well as of the existence of coincidence and the laws of nature contradict the materialist assumption that in the end there are only the smallest material particles moving in empty space. For space and time, coincidences and laws of nature are not themselves material particles moving in space and time. Otherwise space and time would have to move themselves, which would be an absurd assumption. Therefore, this old materialism is a self-contradictory worldview and hence bad philosophy. Marx had lost his way in his opposition to Kant and Hegel, by adopting an all too simple world view from his anti-hero Democritus which had already been rejected by Socrates, Plato and Aristotle for drifty reasons.

But if materialism cannot even explain the spatio-temporal world of physics without contradiction, how should it be able to explain the much more complex behavior of animals with consciousness and of humans with consciousness, language and thinking? According to the materialist worldview the human psyche with its manifold emotions and various faculties, and the human intellect with its ideas, principles, norms and values are all supposed to be only epiphenomena of the human body and therefore more like strange secretions of the brain and nervous system as the central organ of the human body. The human mind is supposed to be not a dynamic mental force, which can control the linguistic thinking and acting of humans through the will, which does not occur in this complex form in any kind of higher mammals or birds.

Matter is said to have produced all these wonders of nature by itself through an incredible series of natural coincidences and lawlike necessities. Matter, mythologized and exaggerated in this way, took over the place of God as a wonderful creative force. In speculative connection to Heraclitus, Spinoza and the Gospel of John, Hegel thought pantheistically of God as a divine Logos. For Hegel, however, unlike for the Deists, the divine Logos is not only an original and creative impulse of the whole world history, which is to develop according to strictly mechanical laws of nature, but it is a creative force still immanent in world history, which produces unforeseeable new events.

For Marx, Hegel’s philosophical-theological speculations were only high-flying projections of a professor of philosophy whose profound intellect no longer worked on the real and concrete problems of the people in the world, but was only meant to justify, support and sanctify the “bourgeois ideology” of the Prussian state. On the basis of his materialist worldview and of his politically motivated hermeneutics of suspicion, Marx was unable to distinguish between right and wrong like Kant and Hegel, and therefore had to devote himself in his further political struggle to the supposedly scientific socialism on its historically necessary path to a utopian communism.

Accordingly, for Marx legal and moral injustice were only temporary moments of a natural-historical process in the struggle for existence and thus merely the expression of historical “contradictions”, i.e. conflicts of interest between human individuals and groups as more or less conscious representatives of economic classes in their historically necessary class struggles. Hence, the ideological mastermind Karl Marx was already mistaken, and not only the two ideologues and activists Marx and Engels or even the revolutionary Lenin and the dictator Stalin. Their supposedly scientific worldview of historical materialism and ideological naturalism was an unscientific ideology or, as they called it, “false consciousness. For, from its beginnings with Democritus to its modern varieties with Feuerbach and Haeckel, materialism is neither a necessary precondition nor a logical consequence of scientific research.

III. Philosophical Problems of Materialism

Materialism, however, is not only an inherently contradictory and therefore untenable worldview, but it also contains a phenomenologically and empirically questionable image of man. Materialism generates a questionable conception of man, because all logicians and mathematicians in their personal experience of logical or mathematical thinking and reasoning, calculating and proving are confronted with evident valid rules of right thinking and reasoning, which simply cannot come from the natural world of material bodies, organisms and brains.

However, not only the rules of logic and mathematics, but also the complex rules of grammar of cultural languages as well as of familiar games and sports, of daily traffic or of an electoral system, etc. are in any case something intelligible that only humans can grasp and understand mentally and intuitively, even if they first have to get to know and internalize these rules in order to follow them habitually and intuitively and no longer consciously and in a controlled way.

Materialism is still empirically questionable, since rules, ideals, principles, norms and values cannot be perceived, observed or found neither in the merely material components of inorganic nature nor in the plant organisms of organic nature. Unconscious rules and behavioral preferences only appear on the next level of higher mammals and birds, as well as in primates and early humans. But in order for unconscious rules and behavioral preferences to become conscious and become accepted ideals, principles, norms and values, it requires cognitive and propositional self-consciousness, freedom of will, linguistic thinking and communication as we have only found it in humans so far.

It is true that we can perceive and observe people who express certain rules, ideals, principles, norms and values in certain situations through their non-verbal behavior and actions or through their verbal speech acts and thought processes. But rules, ideals, principles, norms and values cannot be located in the human brain either, neither on the material and neurophysiological level of the soft and gray protein mass of the brain nor on the functional and neuronal level of the electro-bio-chemical brain processes. There, modern neuroscientists can only ever find neurological processes that correlate more or less well with the behavior and actions, speech and thinking of these people.

Such correlations between brain processes and behavior can indeed be detected by modern neuroscientists by simultaneously observing, identifying and assigning both the external verbal and non-verbal behavior of test persons and the data from their internal brain processes processed into images by computers on a screen. But even then, they will only ever be able to establish certain correlations between types of internal brain processes and types of external human behavior.

But rules, ideals, principles, norms and values are neither directly observable in external human behavior nor identifiable in internal human brain processes. Neither are they identical with external behavior nor with internal brain processes. Rules, ideals, principles, norms, and values are something intelligible that humans can only grasp and intuitively understand, but that they cannot perceive (see, hear, smell, taste, or touch) with their five senses.

There are also other things that people cannot perceive with their senses, such as radioactive rays or infectious viruses. But radioactive rays are inorganic physical micro-objects that can cause severe structural damage to organic cells. And viruses are infectious organic physical micro-objects that can spread extracellularly as virions, but can only reproduce intracellularly. But rules, ideals, principles, norms and values are not physical objects at all and therefore they are neither inorganic nor organic. However they are intelligible structures that only humans can conceptually grasp and intuitively understand and that can be expressed in human dispositions and preferences of thinking and reasoning, behavior and action.

Since the 20th century, however, materialists no longer refer to the old, pre-Socratic philosopher Democritus, like Marx did. But most contemporary materialists still refer to Charles Darwin despite many theoretical ambiguities in his two major works On the Origin of Species and The Descent of Man. Unlike contemporary naturalists, Darwin claimed there that the peculiar nature of man cannot be determined by a few physical characteristics alone, such as upright gait, height, greater cranial and brain volume, lack of fangs, lack of hair all over the body, and innate weakness of instinct.

According to Darwin, human beings differ significantly from all other living beings on earth in a number of psychological characteristics and mental powers, such as the ability to abstract through conceptual thinking, propositional self-awareness, the ability to acquire and use a language with a complicated system of semantic and grammatical rules, the sense of beauty and moral goodness, faith in God and spiritual ideals. Charles Darwin himself was therefore not a clumsy materialist or reductionist naturalist. But very few of his admirers know and understand Darwin’s firm conviction of the special position of man in nature. Instead, they reduce his theory of evolution to Herbert Spencer’s slogan of the survival of those who are best adapted to the environment (survival of the fittest). Unlike Darwin himself, they thus undermine the specifically human ability to recognize what is true and good and to enjoy what is beautiful and sublime.

It is true that contemporary materialists, such as David Armstrong, Mario Bunge, Paul and Patricia Churchland, Daniel Dennett himself rarely called themselves ”materialists”, but rather more often a “naturalists” or “scientific realists”. But this does not change the fact that they have to be able to explain whether or not there are intelligible structures like rules, ideals, principles, norms and values. For the ontological question, what there is in itself and not only for somebody, is the hard case of all philosophical reasoning.

Even W.V.O. Quine, the famous logician and mathematician, behaviorist philosopher of language and scientific realist had admitted that there must be at least quantities (sets) besides the physical objects of modern physics and other natural sciences, because these basal entities of mathematics simply cannot be reduced to physical objects. But quantities, like rules, are also something intelligible.

Most modern naturalists will probably explain that, for example, talk about the rules of chess or basketball and the grammatical rules of their cultural language are only useful fictions or cognitive idealizations, but that in reality there is only the observable rule-compliant and rule-breaking behavior of humans. This sophisticated reinterpretation of our common talk about rules is, however, quite artificial, since in everyday life we all at least talk about rules and rule violations in law and in road traffic, in sports and in games, and assume that they surely do exist.

Moreover, probably not only most scientific ethnologists and linguists, cultural and political scientists, but also pedagogues and psychotherapists, psychiatrists and doctors, lawyers and economists are firmly convinced that in the culture in which they live, work and research, there are of course many different kinds of rules, ideals, principles, norms and values that they study and investigate in their respective fields in order to gain certain insights and influences about them.

Of course, this does not mean that rules, ideals, principles, norms and values are independent spiritual substances in a timeless being, in a platonic heaven or in the eternal spirit of God. But they are definitely something that we can grasp and understand with our human intelligence, because they make a considerable difference and have an impact at least through the personality of people in the social and cultural conventions and traditions of our common world. Therefore, they are preserved and nurtured in the various cultural institutions of education, the arts, religion and law.

But these considerations lead far beyond Marx’ materialist world view and image of Man. Marx, however, was a child of the 19th century and is no longer our contemporary. Today’s Marxists must therefore examine his economic and political conceptions to see whether they can be maintained and defended at all, not only in economic and political, but also in philosophical terms. This applies last, but not least to his materialist view of the world and of humanity, which is relevant for his economic-political studies on labor and surplus value, on property and production, on money and markets, on the “contradictions” or conflicts of interest between wage laborers and owners of means of production, and between workers and capitalists, farmers and big landowners, etc.

But as long as there are phenomenological blindness, empirical deficiencies, logical contradictions and theoretical inconsistencies in the materialist or naturalist conception of man, they will then also affect Marx’s economic and political conceptions and weaken them in their ideological core and in their philosophical presuppositions and consequences. This applies also to the obvious relevance of moral and legal as well as economic and ecological rules, ideals, principles, norms and values in the economic and political behavior and actions of people.

IV. Five Dogmas of Marxism

There are five dogmas of Marxism, which are derived from certain ideological views of Karl Marx and which cannot be blamed for the momentous popularization and radicalization of Engels and Lenin, Stalin and Mao Dse Dung:

1. The dogma of materialist determinism: Being determines consciousness.

This determinist dogma is too general and too vague to be understood and evaluated in detail. If it only states that the consciousness of a certain group or class of people is shaped or influenced by their common living and working conditions as well as by other social, cultural, economic and political conditions, then it is trivial. But to say that human consciousness is “shaped” or “influenced” does not mean that it is “causally determined”. For human beings respond to external conditions with the respective dispositions and potentials of their personality, and their responses are not simply mechanically or causally triggered, like the salivation of Pavlov’s dog. For the individual consciousness of humans this is even less true. Moreover, the psychological dispositions and mental potentials, the processes and states in the consciousness and intellect of individual people are constantly changing due to internal psychological factors and due to external natural or cultural circumstances. Therefore they can hardly be reliably predicted in individual cases.

2. The dogma of the naturalist view of man: humans are mere socio-biological living beings.

This naturalist dogma says that the consciousness and intellect of human beings is completely determined by the socio-biological situation of their body, i.e. organism, brain and nervous system. This naturalist dogma absolutizes the physical conditions and ascending causal influences, but negates the descending personal conditions and activities of mental reflection and rational weighing of options for action and thus the ability of internal will formation and self-determination through freedom of choice between different options in thinking, judging and acting. However, not only current emotions, motivations, and convictions enter into the mental considerations and rational weighing of options for thought, judgment, and action, but also a highly complex aggregate of culturally learned and socially internalized rules, ideals, principles, norms, and values.

3. The dogma of historical materialism: The history of mankind is a historical process with necessary stages of development determined by dialectical “contradictions” or conflicts of interest.

According to the dogma of historical materialism, there is a historically necessary economic-political development from monarchical feudalism through bourgeois revolution to liberalism and from liberalism through socialist revolution to socialism and then through socialist reforms to utopian communism as the supposed final goal of history as a hoped-for peaceful and just society of free and equal people. This development is supposedly controlled by natural laws just as much as the evolutionary development of species. The first half of this dogma, relating to the past, is extrapolated from European history, but the second half, relating to the future, then arises from a secularized messianism.

4. The dogma of naturalization and instrumentalization of normativity.

According to the dogma of naturalization and instrumentalization of normativity, civil law, internalized morality and civil religion are only “bourgeois ideology” in the service of the rich and powerful in order to protect the interests of the owners in the means of production. As ideological instruments of vested interests, they allegedly belong only to the economic-political “super-structure” of the economic-political driving forces of capitalism and will become superfluous in future socialism and utopian communism. Therefore the whole state will then disappear, which according to the utopian “System Program of German Idealism” (1797) is only a “mechanical machinery”. The normativity of morality, law and religion has no objective validity from a naturalistic and scientific point of view, but only a social and instrumental political function. However, with this, the difference between a legitimate constitutional state and an illegitimate unjust state or an arbitrarily ruling autocracy or bureaucracy then disappears.

5. The dogma of the revolutionary socialization of capital.

The dogma of the socialization of capital states that the secret key to the revolutionary overthrow of capitalism on the road from socialism to communism is the political – and if necessary violent – abolition of private property in the means of production. Since the rich and powerful, based on the bourgeois normativity of morality, law and religion, will not voluntarily share their wealth and will not voluntarily give up their power, it is politically necessary and historiographically metaphysically justified to expropriate and disempower them. This is similar to the French Revolution, when it was politically necessary to overthrow feudalism, the monarchy and the clergy by force through a bourgeois revolution. The dependence, poverty and serfdom of the “Third Estate” of workers, peasants and slaves calls for a further socialist revolution. However, as history has taught, there is no guarantee that real existing socialism will not also lead to a political dictatorship of the ideological functionaries of socialism, who, even in this new system, will secure for themselves certain privileges in order to defend them and their thereby consolidated power in a state of injustice with the help of corrupt officials and doctors, judges and police, secret services and militias.

These five Marxist dogmas together form the ideological birth defects of later Marxism and had devastating economic and political consequences in the form of violent socialist revolutions and mass movements with the disastrous result of millions of mass murders in the name of the alleged historical necessity of the transition from liberal capitalism first to authoritarian socialism and then to utopian communism.

V. Five Reliable Economic and Political Observations of Marxism

However, there are also five empirical observations of economic-political Marxism and later cultural Marxism that remain valid:

1. In a free market economy, there is a tendency toward monopolization, i.e., the leading large companies tend to buy up other smaller companies due to their inherent tendency to grow economically and increase their profits, in order to increasingly dominate the market for their respective products alone. This tendency must be regulated by state authorities through antitrust laws and controlled by legitimate intervention. For if individual large companies have gained a monopoly position dominating the entire market and thus too much economic and political power, there is no longer fair competition and thus no functioning market economy. In addition, states and federations then also lose their ability to contain and control the markets for the benefit of citizens and people and are then themselves politically marginalized.

2. In the free market economy there is a tendency towards globalization, i.e. when the demand in their traditional region for its products is saturated and the material and wage costs for their production increase, large companies tend to expand the reach of their distribution and the number of their branches to newer and further regions with lower wage costs and to operate worldwide at most. This thwarts the regulatory plans of governments and federations, as they are increasingly subject to blackmail by the threat of being forced to migrate to foreign countries that are more favorable for them due to lower wage costs and tax burdens in the case of state regulations. In addition, a global network of banks and companies favors tax evasion in tax havens and money laundering through clever transactions.

3. In capitalist societies there is a tendency towards commodity fetishism, i.e. citizens and people develop a superior idolatry of goods, products and brands by making their self-esteem dependent on buying and owning as many of them as possible, thereby increasing their social status. However, this leads to a psychological alienation from their actual human needs and to an addiction-like self-alienation and inhumane reification of human beings. Citizens and people increasingly define themselves as consumers with supposed freedom of choice and do not realize to what extent their short-term subjective and artificial needs are repeatedly controlled by fashions, markets and the influences of the advertising industry. However, their long-term objective and natural needs for mental and physical health and for their chances on the unregulated labor, food and housing markets, as well as their chances for a stable retirement and sufficient pensions, often fall by the wayside.

4. In the free market economy, the economic-political power of banks and stock exchanges is increased, the speculative financial economy with its stock and money transactions, with its tricks of money laundering and tax avoidance at the expense of the tax-paying citizens and people and their legitimate democratic co-determination according to the principle of “one (wo)man, one vote”, is decoupled from the normal market of goods and transactions, production and consumption. This plutocratic tendency weakens not only the people of the state as legitimate sovereign in modern constitutional democracies, but also the legitimate constitutional state and the ecological, economic and political power of parliaments and governments. Such a “market-based democracy” (Angela Merkel) is at the expense of citizens and people because of the lack of regulation of the financial markets, the loss of tax revenues and thus the poverty of public budgets. If, in addition, the national debt becomes immense, the state, with its budget financed by taxes, will at some point no longer be able to pay for the consequential costs of the advancing deterioration of services of general interest and infrastructure. Ultimately, irreparable environmental damage will be added to this for many more generations at the expense of the natural living conditions of plants, animals and people. Thus an insufficiently and unerringly regulated capitalism destroys the natural living conditions of citizens and humans and thus itself in the long run.

5. The elected representatives and governments of democratic constitutional states are effectively disempowered by the prevailing growth and profit interests of globally active banks, stock exchanges and companies. Politicians, driven by economic constraints, only keep up the pretense of a true democracy and, under the growing influence of lobbyists, increasingly pursue the strategic interests of their own clientele in dietary increases, job allocations, political career opportunities and short-term election successes. However, as a result, parliamentarians and government officials, top politicians and ministers in nations and federations are becoming increasingly alienated from the majority of citizens and people. There is understandably growing dissatisfaction with the dysfunctional political system in both political camps, but there are not only radical left-wing uprisings and populist movements of solidarity with the needy against the capitalist plutocracy, as the Marxists hoped, but also right-wing populist tendencies of anti-social attitudes, growing nationalism, increasing racism, greater militarization, and the encroaching activities of secret services and excessive police violence.

Even though Marx’s materialist worldview and his somewhat crude naturalist view of man erred with respect to some fundamental philosophical problems, and even though economic-political Marxism was burdened from the outset with the five ideological dogmas mentioned above, some of his empirical observations have turned out to be largely correct. However, the formative epochal caesura caused by major historical events for the citizens and people of the second half of the 20th century were no longer the French Revolution, as for Kant and Rousseau, nor the French Revolution and the Napoleonic Wars, as for Fichte and Hegel, nor industrialization, nationalism and the Restoration, as for Marx and Engels, but the two, previously unimaginable world wars, the civilisation breakdown of the Shoah, the terror of the Gulag archipelago, the destructive horror of the atomic bombs of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, as well as the proxy wars of the Cold War in Vietnam and Kambosha, Afghanistan and Iraq, etc.

Like Hegel, Marx no longer belongs to our epoch. The contemporary philosophy of the 21st century can no longer easily orient itself by them. But philosophers and historians of philosophy, economics and law can and should still study and research them thoroughly in order to preserve their epochal contributions to the history of culture and ideas, because students and intellectuals can still learn one or the other from them. Their works, if properly interpreted, are capable of curing the collective blindness and mental biases of our own zeitgeist.