Medieval Dignity, Modern Education

In the conclusion of her review of David Walsh’s book, The Politics of the Person as the Politics of Being, Macon Boczek challenges the author’s assertion that the language of rights is required to protect human dignity.[1] Boczek’s reservation about the language of rights is that it has been corrupted by modern philosophy where it now serves as a utopian ideology to relieve us of the burdens of political responsibility. This review sparked an exchange between Walsh and Boczek about the language of rights and whether it still preserved some sense of transcendence to protect human dignity or was so sullied that it had become unmoored from its divine origins and transformed into a secular ideology.[2]

This debate about rights and dignity informs this chapter’s exploration about the nature of dignity and education in the medieval and early modern periods. What do we mean when speak of dignity and education? How did these concepts change over time? What was the relationship between them? And what can the medieval and early modern period tell us about dignity and education today?

Such an examination is instructive because it was in the medieval era where the university was established and in the early modern period where it was transformed. The corresponding concept of human dignity also changed from the medieval to the early modern period. Thus, when we speak about dignity and education today, are we are referring to them as they were understood in the medieval era, the early modern period, or both? Do dignity and education still preserve their original meanings or has it been so transformed in the early modern period that it would no longer be recognizable to a medieval person?

This chapter explores the transformation of the concept of human dignity from the medieval period to the early modern one and how the nature and purpose of education correspondingly changed. It is important to note that during this time the word “dignity” was not associated with the language of rights today; therefore, when I use the word “dignity” in this chapter, I’m referring specifically to the conception of the human being as related to God and nature. In the medieval world dignity consequently is afforded to human beings because of their relationship to God and because they had dominion over nature. The nature and purpose of medieval education therefore is to cultivate these teachings and encourage humans to act rather than produce in the world. By contrast, early modern education, as represented in the writings of Bacon and Descartes, views its purpose to dominate and master nature for practical purposes. This transformation in education is due a transformation in the understanding of dignity where human domination over plants and animals is the sole origin of value in a world devoid of an active God or a normative account of nature.

Medieval Dignity

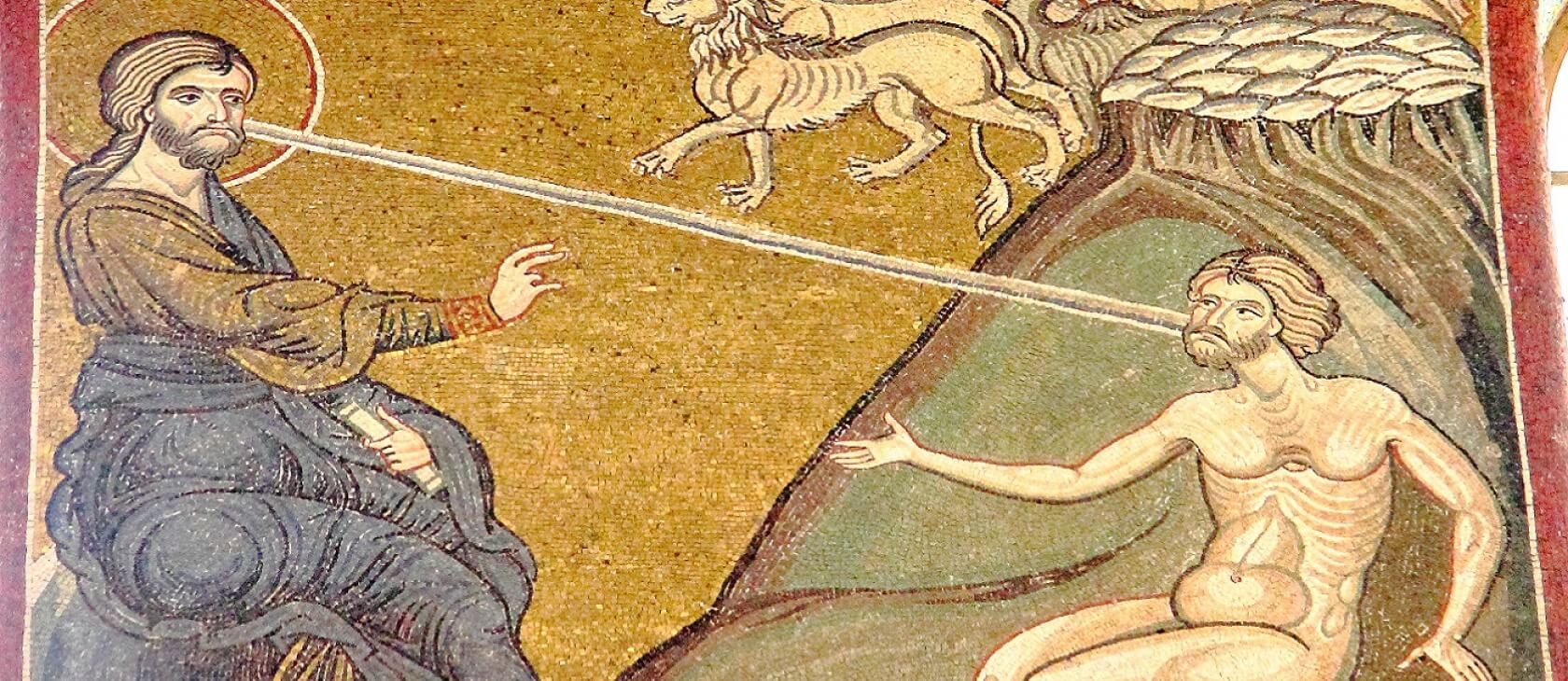

According to classical thinkers in Greece and Rome, human beings are singular and superior among creatures because of their capacity of reason.[3] This idea is also supported by Jews, Christians, and Muslims who assign a dignity to humans in this life and a perfected one hereafter because only humans are capable of faith in the divine.[4] We are the best of all living creatures and therefore have a dominion over nature. This medieval Christian account of human beings – God gave us souls and commanded us to rule over nature – affords only humans a different type of dignity when compared to other creatures.

This dignity is inextricably tied up with our relationship with God. For Aquinas, our moral life, as guided by prudence, is directed towards friendship with God.[5] Our decisions and consequences are evaluated on whether they bring us closer or further away from God. It is this calling from God to seek friendship with Him where human dignity is founded. Because we are made in the image of God and possess an innate desire to seek friendship with Him, dignity is an inherent and fundamental aspect of our existence.

Although originally lost in original sin, our dignity is restored in the sacrifice of Christ where Jesus gave up his life to redeem humankind. The early church fathers invite Christians to accept the divine grace of Christ’s sacrifice, so their dignity would be fully recovered.[6] Aquinas also argues that Christ’s Incarnation provides a model for us to practice the theological virtues of faith, hope, and charity to make us closer to God and thereby afford us a greater manifestation of our dignity.[7] However, certain sins, like murder, can lead us to lose our dignity, although we can remedy these acts through the sacrament of reconciliation.

Dignity consequently is not a static entity but rather a dynamic one as determined by our relationship with God. As we move closer to God, our dignity flourishes; as we move away, our dignity diminishes. The divine intervention in history of Christ’s Incarnation and crucifixion restores the full potential of dignity marred by original sin and provides a model for us to follow in the practice of faith, hope, and charity as guided by prudence. Because human beings embody both material and spiritual reality, we are a microcosm of all reality that resembles God’s creation and Christ’s Incarnation.[8]

The second component of our dignity is God’s command to Adam and Eve to have dominion over the plants and animals (Gen. 1: 26, 28). It is telling that Christian commentators are mostly silent on this injunction, especially when compared to early modern thinkers like Descartes and Bacon. No medieval thinker interprets these verses as giving permission to humans to exploit nature or threaten its integrity; instead they focus on the command to reproduce and connected it with continence.[9] Augustine, for example, understands the passage as speaking to the intellectual superiority of humans and does not comment about human power over nature: the earth one must dominate is the flesh which the soul does by acquiring virtue.[10] With the exception of Basil of Caesarea – who, for example, allows humans to control elephants because man is made in the image of God – Christian thinkers refrain from comment on these verses.[11]

Thus, human dominion over nature does not represent infinite possibilities, as with early modern thinkers. Augustine remarks that the earth is to be “ploughed” rather than exploited for human use: we are to live in a dialogue with nature where the earth was neither fetishized nor subjugated. As rational creatures, we are to discover the reasons already present in nature and bring to fruition what was stored there.[12] God’s calling of Adam and Eve to have dominion over nature was not to dominate it, for, in doing so, we would lose our dignity, but to work with nature. Made in the image of God, we are not the owners of creation but merely its overseers.

The Medieval University

One of the enduring contributions that the medieval era makes to civilization is the university. Prior to the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, intellectual life existed in the monasteries, but population growth, urbanization, and the Gregorian Reforms, particularly in canon law, led bishops to create cathedral schools to train clergy, which eventually became universities when they moved to Bologna (1088), Paris (1150), Oxford (1167), and elsewhere.[13] What distinguishes the university from other types of schools is they were created as a guild of teachers and students without the express authorization of the church or state.[14] They existed as independent, autonomous entities that were internally regulated and protected their members from external intervention.

University teachers were paid by students (e.g., Bologna), the church (e.g., Paris), or the state (e.g., Oxford). Either students (e.g., Bologna) or teachers (e.g., Paris) would run the university with the seven liberal arts taught: arithmetic, geometry, astronomy, music, grammar, logic, and rhetoric.[15] The curriculum also included the Aristotelian philosophies of physics, metaphysics, and moral philosophy. Instruction was in Latin and students were expected to converse in the language. Once graduated, students could pursue further studies in law, medicine, or theology, the last subject considered the most prestigious.[16]

One of the challenges confronting a Christian education was the richness of the pagan intellectual tradition, where the seven liberal arts originated.[17] Early Christians had no schools of their own so they were taught a “Christian” reading of pagan texts where the writings had been distorted to serve Christian aims.[18] In Book II of his On Christian Doctrine, Augustine proposes what a Christian school might look like that takes the Bible as the ultimate norm of education where the liberal arts is inserted into this larger theological framework.[19] This blueprint would later be taken up by Bonaventure’s reduction atrium ad theologiam that characterizes medieval education.[20] However, the rediscovery of Aristotle’s works in the first half of the thirteenth century – a complete, fully developed, pagan philosophy that owed nothing to Christian revelation – posed a problem to Christian education.[21]

Aquinas was able to provide a Christian response where there are two types of wisdom – one known through reason and the other by divine revelation – so that the universe is perfect as it achieves its natural ends.[22] However, divine grace elevates nature by assigning it an end higher than any to which it might aspire. There is a legitimacy and integrity to the natural order but it is enhanced by divine revelation. For Aquinas, a common ground exists in the natural order between Christian and non-Christians while, at the same time, asserting a superiority of Christian truth as revealed to us by grace.

Reason and philosophy therefore have a role to play in understanding the natural world, albeit subordinate to Christian faith, which requires humans to be properly educated in it. This form of education became known as scholasticism which emphasizes dialectical reasoning to resolve contradictions between Christian truth and pagan philosophy.[23] The method begins with a teacher reading an authoritative text followed by commentary with no questions permitted (lectio). Students then reflect on and appropriate the text (meditatio), eventually asking questions (quaestiones), with the discussion of the questions becoming a method of inquiry apart from the lectio and authoritative texts. Finally, disputationes were arranged to resolve controversial quaestiones.[24]

The purpose of the scholastic method is to teach students to resolve the contradictions they encounter in the world, so they can be closer to God. In other words, the liberal arts and the scholastic method is to perfect as much as possible one type of wisdom (reason) while acknowledging that divine revelation (faith) is the ultimate norm that determines all value. This form of education supports the medieval conception of dignity as our friendship with God in the practice of faith, hope, and charity as guided by prudence and in bringing to fruition what already existed in nature. Medieval education forms how students relate and act within the world rather than to master and dominate it, thereby bringing them closer in friendship with God and enriching their dignity.

The Medieval for Today

While this account of education and dignity was in the past, a contemporary account that preserves these insights can be found in two essays by Josef Pieper: “Leisure as the Basis of Culture” and “The Philosophical Act.”[25] In these works, Pieper argues that culture depends upon leisure, and leisure, in turn, depends upon the cult of divine worship – a ritual of public sacrifice that serves as the primary source of our freedom and dignity. Leisure therefore is our fundamental relationship to reality, which celebrates divine worship. It is this celebration, freed from utilitarian calculation, that is the highest form of freedom.

Like Aquinas, Pieper defines two way we can relate to the world: ratio – discursive, logical thought in search of abstractions, definitions, and conclusions – and intellectus – contemplation and intuition that receives the world as it discloses itself to us.[26] According to Pieper, the medieval person believes that intellectus is superior to ratio in how humans relate and understand the world, although both are required for human dignity. The problem of modernity is the prioritization of one over the other. Some think knowledge is only a product of ratio (e.g., Kant, Marx, Weber), while others believe it is passive in nature (e.g., romantics like Jacobi, Schlosser, Stolberg).[27] Genuine knowledge requires both ratio and intellectus, forcing humans to live a paradoxical existence where they are both subjects and objects, actors and acted upon, in this world.[28]

At the core of leisure for Pieper is celebration of divine worship, a sacrifice of something freely given to be used for a non-utilitarian end. For Christians, the cult of divine worship is unique because it is both “a sacrifice and a sacrament”: it is the sacrifice of Jesus Christ and a sacrament because it is celebrated in visible signs.[29] The Incarnation is a visible manifestation of the transcendent reality of God. The Christian celebration subsequently draws us out of the world of ratio and into a culture where we are no longer at the center of creation. The cult reorients our attitudes towards the world where we learn about a reality that is separate from us but still inherently worthwhile and therefore demands celebration.

If ratio and intellectus are ways we relate to the world, then work and philosophy are the manner in which we act within it respectively. For Pieper, work and philosophy are incommensurable acts: the former is satisfaction of needs, the latter the fulfillment of freedom.[30] Work is our labor to fulfill our needs of food and shelter, while philosophy is to provide us a dignity beyond the world of work that resides in the transcendent. Like Christian medieval thinkers, Pieper defines freedom as friendship with God, which furnishes us a dignity that other creatures lack. Enriched by incorporating both ratio and intellectus, the Christian philosopher studies reality as something complicated, expansive, and ultimately mysterious.[31] But this mystery does not make the philosophical enterprise tragic but rather comedic because the Christian philosopher’s quest is structured by the virtue of hope and motivated by a sense of wonder.[32]

Pieper’s conception of Christian philosophy prompts liberal education.[33] However, liberal education is not definable in terms of specific subjects but is an approach to learning – and more broadly to reality – where we study things for their own sake.[34] The purpose of liberal education is to participate in a reality which we contemplate. It is not the mastery and transmission of knowledge; rather, knowledge is the byproduct instead of the objective of liberal education. The aim of liberal education is to transform the mind and character of students, so they will be able to realize the fullness of their dignity, being able to exercise prudential judgment and have friendship with the divine.

Now Pieper is not claiming there is something inherently wrong with training and professionalization as a form of education; rather, he is arguing that such a servile education should not be the only one. Just as both ratio and intellectus is required to relate to the world, and work and philosophy to act within it, both servile and liberal education is needed for society to function and flourish. What concerns Pieper is the predominance of servile education, a favoring of work, and a privileging of ratio at the expense of liberal education, philosophy, and intellectus. This “proletarianization” of society abolishes culture, leisure, and the cult of the divine which makes freedom and dignity possible.[35] The assumption of such societies is that humans are creatures only defined by their labor and therefore can only be free by purely political (the state) or economic (the market) measures.

Modern Dignity

One of the first early modern thinkers to reject the medieval account of dignity and education is Francis Bacon who reorients philosophy towards utility and power rather than contemplation, for the highest human ambition is to “extend the power and empire of the human race itself over the universe of things.”[36] The way to accomplish this mastery is science, which Bacon establishes with his emphasis on experimentation and observation so that “the secrets of nature reveal themselves better through harassments applied by the arts.”[37] This inductive method is to be applied to all facets of knowledge in the hope of providing maximal pleasure to our unlimited desires.[38] Thus, unlike the medieval relational approach to nature, Bacon’s science, as a “different design,” is to “conquer nature by work” in order to better exploit it for human consumption.[39]

Bacon also rejects the scholastic project of resolving contradictions as we perceive them in the world. One does not rely on the “immediate and proper perception” of our senses but instead use our senses to judge the experiment, which, in turn, “judges the thing.”[40] By relying solely on the observations of his experiments as the basis of his science, Bacon can dismiss non-sensory reality like God as unscientific.[41] But even more revealing is that Bacon’s experimental science is concerned only with how things work instead of what they are. In other words, his science neglects the question of substances. According to Bacon, intellectus and philosophy are improper ways to understand and act in the world because only ratio and work provide us the “secrets of nature” that will enable us to be more powerful to rule over “the universe of things.”

Influenced by Bacon, Descartes formulates his own project in the last part of the Discourse on Method:

For these notions have made me see that it is possible to attain knowledge which is very useful in life, and that unlike speculative philosophy that is taught in the schools, it can be turned into a practice by which, knowing the power and action of fire, water, air, stars, the heavens, and all the other bodies that are around us as distinctly as we know the different trades of our craftsman, we could put them to all the uses for which they are suited and thus make ourselves as it were the masters and possessors of nature.[42]

Distinguishing between speculative and practical knowledge, Descartes privileges utility over contemplation, ratio over intellectus, work over philosophy. Although his method is deductive, Descartes, like Bacon, sees knowledge to increase our power over nature. The purpose of Descartes’s new method is the same as Bacon’s new science: to make us masters and possessors “over the universe of things.”

For these thinkers, mastery is connected with their methods as applied to nature. Dignity consequently is defined by our ability to dominate nature because, by adopting this goal that is distance from us, we can stabilize our subjectivity, providing us a certainty as the master of nature. [Dignity consequently is defined by our ability to dominate nature. By adopting this goal, we see nature as an object which we can manipulate and, in the process, stabilize our subjectivity in our ability to be the master of nature.] Since early modern thinkers are either skeptical or reject transcendence, there is no fixed vertical axis for humans to relate with except for nature: there is no reference point by which our dignity can be determined. Nature therefore is the substitute by which we define our worth and respect.

But our relationship with nature is not one of dominion, as in the medieval world, but of exploitation; or, more recently, fetishization in the ideology of radical environmentalism.[43] In either case, our relationship with nature is what stabilizes our subjectivity, provides us a stable identity, in a godless world. Unfortunately, the modern account of nature is not normative and therefore cannot guide us other than to satisfy our needs and wants.[44] We are left only to ourselves to determine what our purpose is and of what our dignity consists.

As MacIntyre has described, this condition has created numerous, rival accounts of what we are, of what our purpose is, and of what our dignity consists.[45] Bacon, Descartes, and other early modern thinkers are responsible for ushering in a new era where dignity is whatever we want it to be now that we are freed from God. Whether this a positive step towards a world of less violence and cruelty, as Pinker claims, or unleashes secular ideologies of mass murder that has characterized much of the twentieth century, as Voegelin argues, is a matter of lived debate.[46]

The Modern University

By the end of the eighteenth century (ending the early modern period that spanned from c. 1500-1800), the number of universities was approximately 143 in Europe with the highest concentrations in the German Empire (34), Italian city-states (26), France (25), and Spain (23) – a 500% increase from the fifteenth century.[47] Universities increasingly came under state control with the faculty governance model becoming more prominent.[48] The curriculum continued to rely upon the works of Aristotle but the infusion of humanist philosophy – the discovery, exposition, and adoption of classical texts and languages into the university and society – reoriented research and teaching to the human rather than the divine.[49] With the studia humanitatis, humanist professors transformed the study of grammar and rhetoric by relying on pagan writers at the expense of church authors to prepare students for politics and business rather than the church.[50]

The new science of Bacon, Descartes, and others led to tensions between scientists and the universities, with universities resistant to change and thereby driving scientists towards private benefactors in princely courts and scientific societies.[51] The creation of this new epistemology of science not only challenged the Aristotelian framework of the university but also initiated the idea that science was an autonomous discipline. Instead of being a general scholar, the specialist arose who put science first and viewed science as a vocation in and of itself. Over time some universities started to accept the new ideas of science, such as adopting Cartesian epistemology or integrating Copernican mathematics into instruction and debate, but the tensions between science and Aristotelianism, the scientist and the general scholar , and external associations and the university continued throughout the early modern period.[52]

By the end of the eighteenth century, the university had changed into what we now recognized as the modern university: Aristotelian philosophy was replaced with science as the epistemological and methodological foci of the university; theology had been dethroned as the apex of knowledge with the humanities firmly established; and knowledge was seen to be disseminated in society and to be of use in the formation of the modern state. The German model of the research university was conceived by Wilhelm von Humboldt and spread throughout the world with universities concentrating on science.[53] With the exception of religious-affiliated universities, theology’s role either disappeared in the university curriculum or morphed into “religious studies” programs.[54]

The dominance of science in the modern university corresponds with the modern conception of dignity as dominance over nature to increase our power and stabilize our subjectivity. Students are educated not in first principles (why) but in the mastery of the mechanics of knowledge (how). The purpose of knowledge is to learn how to better manipulate nature for whatever purpose we deem fit: there is no normative dimension in the modern university education because there is no agreed upon account of human dignity. We are marooned in a world where we learn more about how to do things but without knowing why.

One of the consequences of this conception of dignity and education is the increasing standardization of the university in teaching, research, and governance. Teaching is defined by ratio with standardized metrics assessing whether students have learned; the value of research is determined by algorithmic formulas rather than qualitative evaluation; and universities are governed by an administrative class of managers that are detached pedagogical or intellectual concerns and instead focused on financial and business matters. [and universities are governed by an administrative class of managers who focus on financial and business matters rather than intellectual and pedagogical questions.[55]] This standardization of knowledge and conduct is justified on power and domination. Because it is easier to manipulate reality if is standardized, administrators, researchers, teachers, and students are forced to conform their activities into these metrics to maximize their performance.

The Data of Dignity and Education

In this Foucauldian world of power and metrics, we are pitted against one another in accordance to the neoliberal principles of competition.[56] According to Peck and Tickell, neoliberals have an almost religious “commitment to the extensions of markets and the logics of competitiveness.”[57] Competition is seen as the primary virtue among individuals, corporations, and governments.[58] The model of the market has been extended to all domains and activities in human life, including education and dignity.[59]

To be competitive in the market, one needs metrics to evaluate how well one is performing; thus, individuals, corporations, and governments are in the constant pursuit of “data assemblage and the infrastructures and systems of measurement.”[60] Metrics – whether a scholar’s research impact factor, student evaluation scores, or the size of a university’s endowment – are the very mechanism by which competition is evaluated, affording differentiation among actors and illustrating inequalities among them.[61] But since there is no normative consensus about what constitutes dignity, what is measured and how it is measured is essentially an arbitrary decision by those in power.

One of the consequences of this neoliberal paradigm is to introduce practices and values to the university which has led to underfunded humanities departments, an overcrowded job market, and pressure to publish no matter how trivial the topic.[62] Those disciplines that are amendable to a standardization of metrics, like the STEM fields (science, technology engineering, and mathematics) thrive in such an environment, whereas those fields of knowledge that do not, such as the humanities and arts, suffer. Another consequence of the neoliberal paradigm is the rise in number of adjunct faculty at universities with the number of “core faculty” members, those with tenure, declining and graying.[63] Humanities programs are not as robust as they were in the past because fewer faculty are permanently invested in them. Another result from this paradigm is faculty having to devote more time to committee work, meetings, technology, and other bureaucratic tasks not related to teaching or research.[64] Thus, not only faculty have to do more with less but have to do it in a way that can be measured and evaluated in a standardized metric suitable for administrative consumption.

The Obama administration’s “college scorecard” is illustrative of the neoliberal approach to university education. The scorecard highlights three metrics: the rate of graduation, the average annual cost, and the “salary after attending” (ten years after entering university).[65] Regardless of the problems of ascertaining whether these metrics can accurately reflect reality, the message is clear: a university education is to make money.[66] Certainly financial considerations are reasonable, especially given the rising costs of a university education; however, there are non-monetary values that a university education can offer, such as friendship, civic education, and liberal learning.[67] The danger of the college scorecard is that it influences the behavior not only of administrators, faculty, and staff but also parents, and most importantly, students. Both education and dignity have been transformed into a type of monetary data where your worth is what your wealth is.

In this world defined by the data and money, students are motivated by fear, anxious of being left behind in this winner-take-all world.[68] Formed by a childhood of constant test-taking, scheduled activities, and technological surveillance, today’s students respond to this fear by accumulating achievement upon achievement in an effort to steel themselves against the uncertainty of their future.[69] To be left behind in the globalized economy is to be one of life’s losers. Hence, the constant need and continual efforts for external affirmation – whether in social media, academic achievements, or social status – to validate their choices, career paths, and even spouses.

Because of the competitive demands of the globalized economy, students see themselves as customers of the university and are often treated as such by administrators, staff, and faculty.[70] The university no longer offers academic knowledge but a social experience.[71] With the commodification of the classroom where the student is viewed as a customer, a culture of assessment and technology has been advanced in teaching. Students are continually assessed in quantitative metrics to confirm they are learning and technology is pushed in pedagogy because it accommodates students’ wants in flexible class schedules and their inclinations to use it.[72] Faculty are required to assign assessment, which often they have no input in creating, in their classrooms and write reports afterwards to demonstrate that their students are learning, and are incentivized by administrators with course release-time, monetary compensation, and performance evaluation to incorporate technology into the classroom.[73] Thus, the commodification of the classroom ensures teaching is conducted in standardized, measurable units suitable for technological consumption.

The quality of education is defined by the quantitative measurement of student learning, retention, and postgraduate salaries rather than a student’s character and reflections about life. This numerical assignment and valuing of reality has the illusion of being objective and transparent.[74] This power of data, its apparent objectivity, is particularly attractive to democratic societies, where, according to Tocqueville, individuals believe that everyone has an equal right to understand reality for him- or herself.[75] In democratic societies, each individual relies upon his or her own judgment to make decisions and reduces everything to its practical or utilitarian value: to “accept tradition only as a means of information, and existing facts only as lesson to be used in doing otherwise and doing better.”[76] But because everyone is equal to one another in democratic society, no one is certain that his or her judgment is better than anyone else’s, ultimately yielding a consensus dominated by the majority.

Data is the crystallization of democratic judgment because nobody can object to it: it is objective, transparent, and universally accessible. Data therefore is employed to evaluate university access, faculty scholarship, student learning, and other educational functions. But the assumptions behind the creation and reception of data require examination, for data is a type of scientism, an ideology that assumes the fact-value distinction where facts are derived only from the scientific-technological method and values are products of only subjective prejudice.[77] On the one hand, knowledge is restricted to realities that conform to the scientific-technological method because this process is objective, valid, and universal; on the other hand, any realities outside of this method are seen as illegitimate forms of knowledge because they are unscientific. The use of data by universities, teachers, and students is to de-legitimate a whole set of experiences and knowledge that cannot be standardized or quantified in a pre-given way.

Conclusion

In the modern world, dignity is a type of data. While one may speak about how the value of human rights affords dignity, it is really the amount of wealth and type of accreditations we have that determine our self-respect and self-worth, particularly in a democratic and neoliberal society.[78] We are defined by data that is externally validated, a project made easier with readily-available informational technology that supports social media, electronic communication, and self-monitoring devices. The early modern project of dominating nature to provide us our sense of dignity has transformed itself into a domination of ourselves for technological, standardized ends as determined by those in power. Education consequently is a mastery of material to climb the social hierarchy in the neoliberal market. Dignity is no longer to have power just over nature but over other human beings, too.

Thus, we will in a world [Thus, we live in a world] of unequals, of unequal dignity and education, although some would claim a minimal amount of dignity in human rights is required for society to function.[79] For a medieval person, this world of unequals is mitigated by the Christian promise of the availability that any person can find friendship in God in the practice of faith, hope, and charity. Educational attainment is neither necessary nor sufficient to become closer to God. But for the modern person, the acquisition of the right educational accreditations, which usually requires wealth, is both necessary and sufficient to be part of the “cognitive elite” in today’s society.[80]

The transformation of university education from the medieval liberal arts with its values of ratio and intellectus to the modern curriculum of data and science coincided with a transformation in the understanding of human dignity. Whereas the medievals primarily see dignity residing in our relationship with God, the moderns view dignity as our ability to exploit nature. While the benefits of modern science and data analytics have been tremendous for individuals and society, the absence of a normative consensus haunts our contemporary existence. Even when we find refuge in data, we discover that data by itself reveals nothing about the true, the beautiful, and the good. Whether we can recover the medieval spirit for today, as Pieper attempted, or whether it is even desirable, remains an open question. But it is a question to consider seriously, for, as much as we have gained from modern science and data, we still feel adrift and alone in a world absent of God.

Notes

[1] I would like to thank Richard Avramenko, the Center for the Study of Liberal Democracy at the University of Wisconsin-Madison for supporting my sabbatical which enabled me to write this chapter. I also would like to thank James Greenaway for his invitation to the symposium, “Human Dignity, Education, and Political Society,” at St. Mary’s University in San Antonio Texas and the other participants there where I presented a draft of this chapter and received useful feedback. Finally, I would like to thank Michael Promisel for his thoughtful criticism of this paper.

David Walsh, The Politics of the Person as the Politics of Being (Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press, 2016), 247-48. Macon Boczek, “The Politics of the Person as the Politics of Being,” VoegelinView October 3, 2016. Available at https://voegelinview.com/politics-person-politics/.

[2] David Walsh, “In Defense of Human Rights,” VoegelinView October 5, 2016. Available at https://voegelinview.com/defense-human-rights/; Macon Boczek, “A Response to Professor Walsh,” VoegelinView October 7, 2016. Available at https://voegelinview.com/response-professor-walsh/.

[3] Rémi Brague, The Kingdom of Man (Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press, 2018), 9-16.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Jean Porter, Desire for God: Ground of the Moral Life in Aquinas, Theological Studies 47.1 (1986): 48–68; Mark Nelson, The Priority of Prudence: Virtue and Natural Law in Thomas Aquinas and the Implications for Modern Ethics (Pennsylvania State University Press, 1992); Fred Guyette, “Thomas Aquinas and Recent Questions about Human Dignity,” Diametros 38 (2013): 112-26.

[6] Augustine, “On the True Religion,” in Augustine: Earlier Writings, John H.S. Burleigh, trans. (Philadelphia: Westminster Press, 1958), 329 (16.30); Saint Gregory of Nyssa, On the Making of Man (London: Aeterna Press, 2016), 8, 10; Leo the Great, Christian Sermons (Washington D.C.: Catholic University of America, 1996), 17-19; also see Brague’s The Kingdom of Man, 9-16.

[7] Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologiae, II-II, Question 62, Article 2; III.1.2. Available at http://www.newadvent.org/summa/; also see Servais Pinckaers, “Aquinas on the Dignity of the Human Person,” in The Pinckaers Reader: Renewing Thomistic Moral Theology (Washington D.C.: Catholic University of America Press, 2005), 144–66.

[8] Richard Dales. “A Medieval View of Human Dignity,” Journal of the History of Ideas 38.4 (1977): 577-72.

[9] Jeremy Cohen. “Be Fertile and Increase, Fill the Earth and Master It”: The Ancient and Medieval Career of a Biblical Text (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1989), 309-10.

[10] Augustine, The City of God against the Pagans, R. W. Dyson, ed. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998), 620-1 (XIV.21).

[11] Basil of Caesarea, Homélies sur l’Hexaemeron, M. Naldini, ed. (Milan: Mondadori, 1990), 290 (9.5.11).

[12] Augustine, City of God, 1159-66 (XXII.24).

[13] Walter Rüegg, “Themes,” in A History of the University in Europe. Vol. 1: Universities in the Middle Ages, Hilde Der Ridder-Symoens, ed. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992), 3-34. For more about the Gregorian Reforms, see Harold Berman, Law and Revolution: The Formation of the Western Legal Tradition (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1983).

[14] Rashdall Hastings, The Universities of Europe in the Middle Ages (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1895), 17-18.

[15] Aleksander Gieysztor, “Management and Resources,” in A History of the University in Europe. Vol. 1: Universities in the Middle Ages, Hilde Der Ridder-Symoens, ed. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992), 108-43; Gordon Left, “The Trivium and the Three Philosophies,” in A History of the University in Europe. Vol. 1: Universities in the Middle Ages, Hilde Der Ridder-Symoens, ed. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992), 307-36; John North, “The Quadrivium,” in A History of the University in Europe. Vol. 1: Universities in the Middle Ages, Hilde Der Ridder-Symoens, ed. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992), 337-57.

[16] Peter Moraw, “Career of Graduates,” in A History of the University in Europe. Vol. 1: Universities in the Middle Ages, Hilde Der Ridder-Symoens, ed. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992), 244-76.

[17] For more about the pagan origin and development of the liberal arts, see Kirk Fitzpatrick, “The Third Era of Education,” in Why the Humanities Matter Today: In Defense of Liberal Education, Lee Trepanier, ed. (Lanham: Lexington Books, 2017), 1-36.

[18] For example, Basil of Caesarea, Letters, Volume IV, Letters 249-368. Address to Young Men on Greek Literature (Cambridge: Loeb Classical Library, 1934); also see E. L. Fortin, “Christianity and Hellenism in Basil the Great’s Address Ad Adulescentes,” in Neoplatonism and Early Christian Thought: Essays in Honour of A.H. Armstrong, H.J. Blummenthal and R.A. Markus, eds. (London: Variorum Publications, 1981), 189-211.

[19] Augustine, On Christian Doctrine (London: Pearson, 1958), 31-78.

[20] Bonaventure, Works of St. Bonaventure: On the Reduction of the Arts to Theology, Zachary Hayes trans. (St. Bonaventure: Franciscan Institute of St. Bonaventure University, 1996).

[21] Cary J. Nederman, Medieval Aristotelianism and its Limits: Classical Traditions in Moral and Political Philosophy (London: Routledge, 1997).

[22] Ernest L. Fortin, “Thomas Aquinas and the Reform of Christian Education,” Interpretation 17.1 (1989): 1-17;

Edward Grant, God & Reason in the Middle Ages (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001), 83-114. The other response of outright rejection was only partially pursued in the Condemnations of 1277. Josef Pieper, Scholasticism: Personalities and Problems of Medieval Philosophy (South Bend: St. Augustine’s Press, 2001), 126-35.

[23] Edward Grant, God & Reason in the Middle Ages, 148-81.

[24] George Makdisi, “The Scholastic Method in Medieval Education: An Inquiry into Its Origins in Law and Theology,” Speculum 49.4 (1974): 640-61; Willem J. Van Asselt, Introduction to Reformed Scholasticism (Grand Rapids: Reformation Heritage Books, 2011), 59-62.

[25] Both essays are in Josef Pieper, Leisure as the Basis of Culture (Indianapolis: Liberty Fund, 1952); also see Lee Trepanier, “Culture and Education in Josef Pieper’s Thought,” in The Democratic Discourse of Liberal Education (Cedar City: Southern Utah University Press, 2009), 118-33.

[26] Ibid., 6-10.

[27] Ibid., 8, 11.

[28] Ibid., 26-30. Voegelin also provides a similar account of living this paradoxical existence that elides the subject-object dichotomy. Eric Voegelin, Order and History V: In Search for Order (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1987).

[29] Pieper, Leisure as the Basis of Culture, 52.

[30] Ibid., 63-66.

[31] Ibid., 128-32.

[32] Ibid.; also see Ibid., 95-113.

[33] Ibid., 48-50.

[34] For more, see Lee Trepanier, “Let’s Save Liberal Education by Rethinking It,” Law and Liberty, December 13, 2018. Available at https://www.lawliberty.org/author/lee-trepanier/; also see Aristotle, Politics, trans. Carnes Lords (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2013), 225-27 (VIII.3).

[35] Pieper, Leisure as the Basis of Culture, 41-44.

[36] Francis Bacon, The New Organon, Lisa Jardine, ed. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003), 100.

[37] Ibid., 81, 11; also see Paolo Rossi, Francis Bacon: From Magic to Science (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1968) and Lisa Jardine’s introduction to Francis Bacon, The New Organon, Lisa Jardine, ed. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003), vii-xxviii.

[38] Ibid., 98.

[39] Ibid., 16.

[40] Ibid., 18; For Bacon’s rejection of scholasticism, see Ibid., 8, 11, 16.

[41] For Bacon’s denouncement of philosophy and theology, see The Advancement of Learning (London: Dent Publishing, 1973), 37.

[42] René Descartes, A Discourse on the Method, Ian Maclean, trans. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006), 51; also see Brague, The Kingdom of Man, 70-71.

[43] For example, see Joel Garreau, “Environmentalism as Religion,” The New Atlantis 2010. Available at https://www.thenewatlantis.com/publications/environmentalism-as-religion; Keith Makoto Woodhouse, The Ecocentrists: A History of Radical Environmentalism (New York: Columbia University Press, 2018).

[44] For more about the difference between classical/medieval and modern understandings of nature, see Lee Trepanier, “Nomos, Nature, and Modernity in Brague’s The Law of God,” The Political Science Reviewer 38.1 (2009): 31-49.

[45] Alasdair MacIntyre, After Virtue: A Study in Moral Theory (Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press, 1981), 1-50.

[46] Steven Pinker, The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence has Declined (New York: Viking, 2011); Eric Voegelin, Modernity Without Restraint: The Political Religions; The New Science of Politics; and Science, Politics, and Gnosticism (The Collected Works Volume 5), Manfred Henningsen, ed. (Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 2000); also see John Gray, Straw Dogs: Thoughts on Humans and Other Animals (London: Granta Books, 2003) and Black Mass: Apocalyptic Religion and the Death of Utopia (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2007).

[47] Guy Neave, “Patterns,” in A History of the University in Europe. Vol. 1: Universities in the Middle Ages, Hilde Der Ridder-Symoens, ed. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992), 31-72; Paul F. Grendler, “The Universities of the Renaissance and Reformation,” Renaissance Quarterly 57.1 (2004): 1-42.

[48] J.C. Scott, “The Mission of the University: Medieval to Postmodern Transformations,” Journal of Higher Education 77.1 (2006): 10-13.

[49] Andris Barblan, “Epilogue: From the University in Europe to the Universities of Europe,” in A History of the University in Europe. Vol. 1: Universities in the Middle Ages, Hilde Der Ridder-Symoens, ed. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992), 550-74; Paul F. Grendler, The Universities of the Italian Renaissance (Baltimore: John Hopkins University, 2002), 197; Grendler, “The Universities of the Renaissance and Reformation,” 12-13, 23.

[50] For more about the studia humanitatis, see Paul F. Grendler, Schooling in Renaissance Italy Literacy and Learning, 1300-1600 (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1989), Merry E. Wiesner-Hanks, Early Modern Europe, 1450-1789 (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2006).

[51] Richard S. Westfall, The Construction of Modern Science: Mechanism and Mechanics (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1977), 105; Mordechai Feingold, “Tradition vs Novelty: Universities and Scientific Societies in the Early Modern Period,” in Revolution and Continuity: Essays in the History and Philosophy of Early Modern Science, P. Barker and R. Ariew, eds. (Washington D.C.: Catholic University of America Press, 1991), 46-62.

[52] John Gascoigne, “A Reappraisal of the Role of the Universities in the Scientific Revolution,” in Reappraisals Scientific Revolution, Robert S. Westman and David C. Lindberg, eds. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990), 207-60; Feingold, “Tradition vs Novelty.”

[53] For more about German research university, see Lee Trepanier, “A Philosophy of Prudence and the Purpose of Higher Education Today,” in The Relevance of Higher Education, Timothy L. Simpson, ed. (Lanham: Lexington Books, 2013), 1-23; Chad Wellmon, Organizing Enlightenment: Information Overload and the Invention of the Modern Research University (Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press, 2015).

[54] For more about the changing nature of religion in the research university, see Thomas Albert Howard, Protestant Theology and the Making of the Modern German University (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006).

There still are universities today with religious affiliation where theology plays a prominent role, but most universities, particularly the most prestigious ones, are secular institutions. For example, see Hanna Rosin, God’s Harvard: A Christian College on a Mission to Save America (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2007); Alasdair MacIntyre, God, Philosophy, Universities: A Selective History of the Catholic Philosophical Tradition (Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield, 2009).

[55] Bok, Derek. 2004. Bok, Universities in the Marketplace: The Commercialization of Higher Education (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2004); Richard Arum and Josipa Roksa, Academically Adrift: Limited Learning on College Campuses (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2011); Benjamin Ginsberg, The Fall of Faculty: The Rise of the All-Administrative State University and Why It Matters (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011); Martin J. Finkelstein, Valerie Martin Conley, Jack H. Schuster, The Faculty Factor: Reassessing the American Academy in a Turbulent Era (Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press, 2016); Marilee J. Bresciani Ludvik and Ralph Wolff, Outcome-Based Program Review: Closing Achievement Gaps In- and Outside the Classroom with Alignment to Predictive Analytics and Performance Metrics (Sterling: Stylus Publications, 2018); also see Lee Trepanier, ed., The Democratic Discourse of Liberal Education (Cedar City: Southern Utah University Press, 2009); ed., Liberal Arts in America (Cedar City: Southern Utah University Press, 2012); “A Philosophy of Prudence and the Purpose of Higher Education Today”; Lee Trepanier, ed., Why the Humanities Matter Today; “The Public Value of Higher Education,” Expositions 12.2 (2018): 121-31; “The Character Model for the American University,” Expositions 12.2 (2018): 132-51; “Why Students Don’t Suffer” in Suffering and the Intelligence of Love in the Teaching Life: In Light and in Darkness, Sean Steel and Amber Homeniuk, eds. (Palgrave Macmillan, 2019), 159-82.

[56] Michel Foucault, Security, Territory, Population: Lectures at the Collège de France 1978-1979 (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2007); Lectures on the Will to Know: Lectures at the Collège de France 1970-1971 and Oedipal Knowledge (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013); Pierre Dardot and Christian Lavel. The New Way of the World: On Neoliberal Society (London: Verso, 2013), 4.

[57] Jamie Peck and Adam Tickell, “Neoliberalizing Space,” in Spaces of Neoliberalism: Urban Restructuring in North America and Western Europe, Neil Brenner and Niki Theodore, eds. (Oxford: Blackwell, 2002), 33-57.

[58] David Harvey, A Brief History of Neoliberalism (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005), 65.

[59] Wendy Brown, Undoing the Demos: Neoliberalism’s Stealth Revolution (New York: Zone Books, 2015), 31.

[60] David Beer, Metric Power (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010), 14-22; also see Jerry Z. Muller, The Tyranny of Metrics (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2018).

[61] This is particularly notable in the ranking of universities. See Craig Totterow and James Evans, “Reconciling the Small Effect of Ranking on University Performance with the Transformational Cost of Conformity,” in The University Under Pressure, Elizabeth Popp Berman and Catherine Paradeise, eds. (Bingley: Emerald Group Publishing, 2016), 265-301.

For more about faculty impact factor, see Peter Weingart, “Impact of Bibliometrics upon the Science System: Inadvertent Consequences,” Scientometrics 62.1 (2005): 117-31; Christian Fleck, “Impact Factor Fetishism,” European Journal of Sociology 54.2 (2013): 327-56.

[62] Anthony Kronman, Education’s Ends: Why Our Colleges and Universities Have Given Up on the Meaning of Life (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2008); Mark Taylor, Crisis on Campus: A Bold Plan for Reforming Our Colleges and Universities (New York: Knopf, 2010). For criticism, see Martha Nussbaum, Not for Profit: Why Democracy Needs the Humanities (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2010); Trepanier, Why the Humanities Matter Today; Marina Warner, “Diary,” London Review of Books September 11, 2014. Available at https://www.lrb.co.uk/v36/n17/marina-warner/diary; Ron Srigley, “Dear Parents: Everything You Needed to Know About Your Son’s and Daughter’s University But You Don’t,” The Los Angeles Review of Books December 9, 2015. Available at https://lareviewofbooks.org/article/dear-parents-everything-you-need-to-know-about-your-son-and-daughters-university-but-dont/#!

[63] Finkelstein et al., The Faculty Factor, 94-96, 137-38, 174-81, 198-99, 206-16.

[64] Ibid., 341-65. For some of the problems about teaching in an environment that expects standardization, see Lee Trepanier, ed. The Socratic Method Today: Student-Centered and Transformative Teaching in Political Science (London: Routledge, 2017) and The College Lecture Today: An Interdisciplinary Defense for the Contemporary University (Lanham: Lexington Books, 2019).

[65] Jonathan Rothwell, “Understanding the College Scorecard,” Brooking Institute September 28, 2015. Available at https://www.brookings.edu/opinions/understanding-the-college-scorecard/.

[66] Ibid. For criticism, see Nicholas Tampio, “College Rating and the Idea of the Liberal Arts,” JSTOR Daily July 8, 2015. Available at https://daily.jstor.org/college-ratings-idea-liberal-arts/.

[67] William Zumeta, David W. Brenman, Patricia M. Callahn, Joni E. Finney, Financing American Higher Education in the Era of Globalization (Cambridge: Harvard Education Press, 2012); Joel Best and Eric Best, The Student Loan Mess: How Good Intentions Created a Trillion-Dollar Problem (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2014); Charlie Eaton, “Still Public: State Universities and America’s New Student-Debt Coalitions,” PS: Political Science & Politics 50.2 (2017): 408-12.

[68] Daniel Brook, The Trap: Selling Out to Stay Afloat in Winner-Take-All-America (New York: Times Books, 2007); Ron Srigley, “Dear Parents,”; Benoit Denizet-Lewis, “Why are More American Teenagers Than Ever Suffering From Severe Anxiety,” New York Times October 11, 2017. Available at https://www.nytimes.com/2017/10/11/magazine/why-are-more-american-teenagers-than-ever-suffering-from-severe-anxiety.html; Greg Lukianoff and Jonathan Haidt, The Coddling of the American Mind: How Good Intentions and Bad Ideas Are Setting Up a Generation for Failure (New York: Penguin, 2018); Lee Trepanier, “Why Students Don’t Suffer,” in Suffering and the Intelligence of Love in the Teaching Life: In light and Darkness, Sean Steel and Amber Homeiuk, eds. (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2019), 159-82.

[69] David Brooks “The Organizational Kid,” The Atlantic April 2001. Available at https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2001/04/the-organization-kid/302164/; William Deresiewicz, Excellent Sheep: The Miseducation of the American Elite and the Way to a Meaningful Life (New York: Free Press, 2014).

[70] Bok, Universities in the Marketplace; Christopher Newfield, The Great Mistake: How We Wrecked Public Universities and How We Can Fix Them (Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press, 2016); Louise Bunce, Amy Baird, Siân E. Jones, “The Student-as-Consumer Approach in Higher Education and its Effect on Academic Performance,” Studies in Higher Education 40.11 (2017): 1958-78.

[71] Ben Ansell and Jane Gingrich, “Mismatch: University’s Education and Labor Market Institutions,” PS: Political Science & Politics 50.2 (2017): 423-25; Lukas Graf and Justin W. Powell, “How Employer Interests and Investments Shape Advanced Skill Formation,” PS: Political Science & Politics 50.2 (2017): 418-22.

[72] John Palfrey and Urs Gasser, Born Digital: Understanding the First Generation of Digital Natives (New York: Basic Books, 2008); Lee Trepanier, Technology, Science, and Democracy (Cedar City: Southern Utah University Press, 2008).

[73] Linda Suskie, “Why Are We Assessing?” Inside Higher Ed October 26, 2010. Available at https://www.insidehighered.com/views/2010/10/26/why-are-we-assessing; Rena M. Palloff and Keith Pratt, Excellent Online Instructor Strategies for Professional Development (Hoboken: Wiley, 2011).

[74] Luciano Floridi, The 4th Revolution: How the Infosphere is Reshaping Human Reality (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014); Beer, Metric Power, Cathy N. Davidson, The New Education: How to Revolutionize the University to Prepare Students for a World in Flux (New York: Basic Books, 2017).

[75] Lee Trepanier, “Tocqueville, Weber, and Democracy: The Condition of Equality and the Possibility of Charisma in America,” in Political Rhetoric and Leadership in Democracy, Lee Trepanier, ed. (Cedar City: Southern Utah University Press, 2011), 22-48.

[76] Alexis de Tocqueville, Democracy in America: Volume 2, Phillips Bradley, trans. (New York: Vintage Classics, 1990), 3.

[77] Lee Trepanier, “The Recovery of Science in Eric Voegelin’s Thought,” in Technology, Science, and Democracy, Lee Trepanier, ed. (Cedar City: Southern Utah University Press, 2008), 44-54.

[78] For more about the universality of human rights and its validity in the modern world, see Jack Donnelly, Universal Human Rights in Theory and Practice (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2013); Macon Boczek, “A Response to Professor Walsh.”

[79] For liberal society, see John Rawls, The Law of People (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1999); Joshua Cohen,“Minimalism about Human Rights: The Most We Can Hope For?” Journal of Political Philosophy 12.2 (2004): 90–213; Michael Ignatieff, The Lesser Evil (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2004); James Nickel, Making Sense of Human Rights (Malden: Blackwell Publishing, 2007).

[80] The term “cognitive elite” comes from Charles Murray and Richard J. Hernstein, The Bell Curve: Intelligence and Class Structure in American Life (New York: Free Press, 1994).

This was originally published in Human Dignity, Education, and Political Society, ed. James Greenaway (Lexington Books, 2020).