Mormons in the American Imagination

In recent years, Mormonism has been the focus of unprecedented media interest. What some have called “The Mormon Moment,” spurred by Mitt Romney’s 2012 presidential campaign and an increased public relations effort by the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (or, more commonly, the LDS Church) itself, has resulted in significant screen-time for a religion which previously seemed to be a bit camera shy.1 This attention comes both from inside and outside of the church, and spans the gamut of today’s media outlets: reality shows and scripted television series, radio, movies, books, and even Broadway—not to mention blogs, news articles, and network news magazines. The coverage is certainly widespread, and as a result, the American people are shaping a collective image of what Mormonism is and what its influence on their lives should be. But what is this image? Who are the key players in creating it? And how does this affect American politics?

Most often, media about Mormons is written and produced by those who are not of the faith. These portrayals vary in their motivation and accuracy regarding Mormon culture and theology. Still, they together are representative of a collective perception of the faith—because for many, what they see on TV is all they know of Mormonism. Therefore, it is useful to look at how the public consciousness of Mormonism and the perception of its people and its principles are shaped by and demonstrated through mainstream media attempts to put the group in the spotlight.

Today more than ever there is an outpouring of media created by Mormons themselves. Often, their subject matter does not deal directly with their belief; but, in some instances, members do confront issues of their faith head-on: from insular theology to the religion’s relationship to homosexual members. While most of these messages are not apologetic in aim and are not formally endorsed by the LDS Church, they allow a unique opportunity for Mormon members to speak for themselves and to show the world that they are not part of a strange and secretive sect but are part of mainstream society and culture. What messages mainstream society—and Mormons themselves—choose to tell reveal a minority faith that has a surprisingly robust voice in American culture and politics today.

Stereotypes of Mormons

The portrayal of Mormons by non-Mormons in American mainstream popular culture has followed two extremes: they are seen either as the epitome of all-American and wholesome values of family, clean living, and material success or as secretive, strange, and suspicious, with sacred temple rites, special garments, and a murky past that includes polygamy. The first set of values is personified in shows like Donny & Marie (ABC, 1976-1979), while the second set is spelled out in the more recent show Big Love (HBO, 2006-2011). These inconsistent portrayals of Mormons in the popular media may be entertaining, but they also confuse the reality and leave the public wondering what the true face of Mormonism really looks like.

In this sense, Mormons are both familiar and unfamiliar to the American public imagination. On the one hand, Mormons are the successful, helpful, and courteous neighbors that Americans want to have next door, while on the other they are the ones who have secretive temples and strange Bibles and talk in a coded language. These disconcerting depictions are reflected in Mormons’ own desire to be accepted by mainstream American society while at the same time adhering to beliefs and practices that run counter to it. This tension within Mormonism and in the popular portrayals of them embodies a tension within American popular culture: a simultaneous affirmation and critique of American values. By both asserting and questioning American values, Mormons have become a key voice in the ever-shifting conversation regarding just what it is that the American people stand for.

Donny and Marie Osmond were the first Mormons to break into American mainstream popular culture who were consistent with the all-American values of family, civility, and success. Donny emerged from the Osmond Brothers as a teen idol in the early 1970s with songs that became pop hits, such as “Go Away Little Girl” and “Puppy Love.”2 He and his sister, Marie, who was a country singer, had a variety show called Donny & Marie that featured songs performed by the two. At that time, they were the youngest entertainers in television history to host their own variety show. When the show was canceled, Donny admitted that his public image was damaged because he was perceived by the public as “unhip” and as a “boy scout” (Burgess 1999). His clean-cut, all-American image was so damaging to his future career that one professional publicist even suggested that he should purposefully get arrested for drug possession in order to change it (“Donny Osmond” 2004).3

Both Donny and Marie would have later success in their careers, although it never would reach the level of fame they achieved in the late 1970s. There would be other famous Mormon public figures—Gladys Knight, Steve Young, Johnny Miller—who offered differing portrayals of the LDS faith, some more positive than others. For most, acceptance would come at the cost of being connected with a conservative America. Those in popular culture who were secular and liberal would portray Mormons differently.

In fact, except for Donny and Marie Osmond, positive portrayals of Mormons in American popular culture are rare. One of the most popular negative representations is HBO’s television series Big Love, which depicted a contemporary polygamist who lives in Salt Lake City with his three wives and seven children. Although the LDS Church renounced the practice of polygamy in the late nineteenth century, the family is described as Mormon (see Havrilesky 2006; Ryan 2006; Poniewozik 2007), leading the LDS Church to release an official statement about the show:

“The Church has long been concerned about the continued illegal practice of polygamy in some communities, and, in particular about persistent reports of emotional and physical child and wife abuse emanating from them. It will be regrettable if this program, by making polygamy the subject of entertainment, minimizes the seriousness of the problem . . . placing the series in Salt Lake City, the international headquarters of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, is enough to blur the line between the modern Church and the program’s subject matter, and to reinforce old and long-outdated stereotypes. . . . Big Love, like so much other television programming, is essentially lazy and indulgent entertainment that does nothing for our society and will never nourish great minds. (The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints 2006).”

In response, Carolyn Strauss, president of HBO Entertainment, stated, “It is interesting how many people are ignorant about the Mormon church and think that it [the LDS Church] actually does condone polygamy. So in an odd way, the show is sort of beneficial in drawing that distinction” (Wilson 2006). HBO also assured the LDS Church the show would not be about Mormons of the LDS Church. Whether such a distinction is made by viewers is unclear.

However, both the LDS Church and HBO recognize the negative association in the American public mind between polygamy and Mormonism irrespective of the contemporary truth. Big Love continued to create controversy when in 2009 the show recreated a temple ceremony, which Mormons consider sacred and therefore secret to non-Mormons. The creators justified their decision as being “a very important part of the story” and issued an apology in case they had offended anyone. As Mormon themes became more woven into the show, the LDS Church was placed in a difficult position. On the one hand, if it were to call for a boycott, unwanted media attention would be directed at the show and possibly would raise Mormons’ past association with polygamy. On the other hand, to ignore the show could be construed as condoning it. The LDS Church chose to express continual disapproval of the show for being vulgar (rather than for being anti-Mormon) and hope that the negative depictions of Mormons would not have any long-term harmful effect on the Church. It also suggested that individual members who were offended at the misrepresentation of the temple ceremony could boycott the show (The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints 2009). The LDS Church’s response was similar to other religious organizations’ reactions to negative portrayals of their beliefs and practices: issue a condemnation not on religious grounds but for reasons of poor taste while reaffirming the strength of one’s organization and encouraging its members to protest it as Americans rather than as specific religious believers.

Similar to Big Love is The Learning Channel’s Sister Wives (2010-present): a reality series based on the family life of polygamist Kody Brown, his four wives, and 17 children. It is important to note that Brown and his family are not members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, which has not supported polygamy since 1890 (in fact, any members of the mainstream LDS Church who practice polygamy are excommunicated). Rather, they are members of a fundamentalist sect, the Apostolic United Brethren, which separated itself from mainstream Mormonism in the late 19th century. Still, the correlation between Mormonism and polygamy in the public mind remains near the surface. The Brown family has received a warm reception from its television audience, but has been frowned upon by state officials in Utah, who investigated the family on charges of bigamy, causing the family to leave the state and relocate to Nevada. Kody and his wives were interviewed by Oprah Winfrey just after the show premiered in 2010, where they described themselves as an average American family with common values (“Inside the Lives of a Polygamist Family” 2010).

Mormonism has also played smaller roles in recent scripted drama, though the portrayal has not been favorable. In the Cold Case episode “Creatures of the Night” (CBS, aired May 1, 2005), a serial killer, known as the “Mormon kid,” hears God in his head; his aunt dismisses the idea that he is crazy, saying, “Joseph Smith heard an avenging voice, so did Brigham Young” (see Hicks “Mormonism” (Trepanier & Newswander), 7 2005). In spite of the warning that the show is fictional and does not depict any actual persons or events, the equation is clear: Mormons are strange people because of their beliefs and practices.

This same equation is also used in the Law & Order episode “Lost Boys” (NBC, aired November 19, 2008), where (again with the warning that the show is fictional) the Mormon characters are portrayed as polygamists. Lighthearted but still insensitive to Mormons was the running gag on Boston Legal (ABC, 2004-2008) that one of the show’s main characters will receive letters, presumably from angry viewers, when he mocks a female character by asking whether Mitt Romney ever wanted her for one of his wives (see “Tea & Sympathy,” aired May 1, 2007). In these and other fictional shows, Mormons are misrepresented as practicing polygamy and holding strange and bizarre beliefs. The all-American and wholesome values of Donny and Marie are discarded for the strange and sensational.

However, there are some portrayals of Mormons in mainstream American popular culture that are more positive, though not as traditional as the Donny and Marie model. For example, in the South Park episode “All about Mormons” (Comedy Central, aired November 19, 2003), Mormon characters (particularly Joseph Smith Jr.) are lampooned but in a good-nature manner, with the Mormon Harrison family depicted as polite, family-oriented, and successful. Although the story questions the religious origins of Mormonism, the Harrison family, particularly their children, are cast in a sympathetic light as victims of religious bigotry by the story’s main characters. In another episode, “Super Best Friends” (aired July 4, 2001), Joseph Smith, along with other religious founders like the Buddha and Moses, joins forces with Jesus to fight David Blaine, a street magician who has superpowers. In fact, in the South Park world, it is only the Mormons who have predicted the afterlife correctly, with members of the other religions condemned to hell. Of all the characters portrayed in the series, it is only the Mormons who are consistently represented as “compassionate, or even courteous” (Evans 2006).

Another ambiguous portrayal of Mormons appears in the HBO television miniseries Angels in America (2003), adapted from the play by Tony Kushner. Mormon characters are prominent in Angels in America, as are Mormon beliefs: the notion of prophecy, the sacred book and angels, and the conceptualization of history as millennial. Mormons understand time as a process of evolution and progress and hold out the possibility of unlimited growth, as do the angels in the show. Just as the early Mormons claimed an ideology of progress that was beyond the progress of Jacksonian democracy, the show advocates a utopianism that is beyond most contemporary ideologies of progress (Bushman 1984: 170). As the nineteenth-century Mormons were persecuted and forced to flee westward, so were homosexuals treated with prejudice and discrimination in the twentieth.4In both the show and in early Mormon history, the United States is understood as a place with a blessed past and a millennial future within a generation’s grasp.

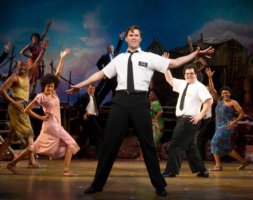

More recently, the Broadway and Tony-awarding musical, The Book of Mormon, portrays Mormons as naïve but well meaning in their attempt to convert Uganda villagers to Mormonism. Created by South Park co-creators Trey Parker and Matt Stone, and Avenue Q co-creator Robert Lopez, The Book of Mormon satirizes organized religion with the conclusion that religion literally interpreted causes more harm than good. Consequently, religion should be understood metaphorically in order to positively contribute to society. The point is underscored at the end of the play, with the Book of Mormon replaced with The Book of Arnold, around which everyone on stage rallies. In spite of their strange beliefs and practices, Mormons are seen as a fundamentally decent, optimistic, and sincere people who want to do good in the world.

Most of the critical response to the musical has been positive, and even the LDS Church did not condemn The Book of Mormon outright. Its only official response was to say that the musical is “an attempt to entertain audiences for an evening, but the Book of Mormon as a volume of scripture will change people’s lives forever by bringing them closer to Christ” (Kirkland 2011). Michael Otterson, the head of Public Affairs for the LDS Church, commented about the musical as a “parody [that] isn’t reality, and it’s the very distortion that makes it appealing and often funny.” However, Otterson feared that The Book of Mormon also reinforces some of the common prejudices against the Church: “the danger is not when people laugh but when they take it seriously—if they leave a theater believing that Mormons really do live in some kind of a surreal world of self-deceptions and illusions” (Otterson 2011).

Interestingly, more balanced portrayals of Mormons have come in reality television series like The Real World (MTV, 1992-present), Survivor (CBS, 2000-present), American Idol (Fox, 2002-present), America’s Next Top Model (CW, 2003-present), The Biggest Loser (NBC, 2004-present), Dancing with the Stars (ABC, 2005-present), and others. Here Mormons are shown as friendly, courteous, and hardworking people who have beliefs and practices characteristic of conservative and religious America. An example of conservative values sticking out in a secular culture can be found on the show Survivor, where the participant Neleh Dennis brought her scriptures as her luxury item to the island and another participant, Ashlee Ashby, woke up at five o’clock in the morning every day to drive thirty minutes to church to study the Bible prior to the show.5 In some parts of the country, these women would be viewed as role models; in others, they would be objects of ridicule. The clash between religious and secular values not only creates conflict on television, but it also reflects the political and cultural conversation that is taking place in the United States today. When Julie Stoffer in The Real World had to explain and justify her Mormon religion to her roommates, she became the central character of the series as the lone conservative and religious voice in a liberal and secular America.6

The advantage of having Mormons in reality television series is that they are able to represent an America that is both familiar and strange: conservative and religious but not well known or understood. As Julie Stoffer said, “One of the good things that will come out of this is that it’s getting people talking about Mormonism. . . . If it takes a couple kids going on ‘American Idol’ to make that happen, well, damn it, good!” (Atkinson 2008). This not only allows a natural conflict of religious and secular values, but it also invites curious viewers to ask what constitutes Mormonism and, more broadly, what constitutes America.

What may be more remarkable than the sizable number of Mormon contestants in reality television series is their acceptance by mainstream American popular culture and their ability to maintain their religious identity. Ken Jennings, who holds the longest winning streak on the U.S. game show Jeopardy (NBC/syndicated, 1964-present) was so well received by mainstream popular culture that corporations like Microsoft, Cingular Wireless, and All State Insurance sought his public endorsement (see Jennings 2006). Jennings did not hide the fact that he was Mormon—he stated that he would donate some of his $3 million earnings to the LDS Church (as “Mormonism” (Trepanier & Newswander), 11 well as to National Public Radio)—but he did not make it the defining issue for his public persona.

Still, some in the mass media depicted Jennings as a Mormon, as opposed to simply a successful American. Jennings himself addressed this issue directly when he wrote an article in the New York Daily News asking the public to stop slandering his Mormon faith, especially in light of Massachusetts governor Mitt Romney’s run for the 2008 Republican presidential nomination (Jennings 2007). Thinking that his religion had been “effectively mainstreamed” (“Being a Mormon was like being Canadian, or a vegetarian, or a unicyclist,” he said), Jennings was surprised to see the biased coverage Mormons received in the mass media, such as “Lawrence O’Donnell’s bizarre anti-Mormon explosion on ‘The McLaughlin Group’” or “Christopher Hitchens, who called my church ‘an officially racist organization.’” Finding himself, like many Mormons, a target of unfair stereotypes from the mainstream media, Jennings concluded with a plea for tolerance and civility, as well as a clarification of the LDS Church’s positions on blacks and polygamy.

Although the increasing visibility of Mormons in American popular culture could be interpreted as a sign of mainstream acceptance, one has to ask why the media so often, and stereotypically, make a point of a person’s or a character’s Mormon religion. Compared to other religious groups, Mormons are overwhelming a target of negative stereotypes, with their beliefs and practices considered strange rather than mainstream. Additionally, shows like Big Love and Sister Wives continue to play on the old correlation between mainstream Mormons and polygamy—a false and often damaging association.

Past the Mormon Stereotype

Members of the LDS Church have also made their mark on the big screen in acting, producing, screenwriting, composing, and directing both in independent and blockbuster films. Whether their faith is mentioned publicly or not, the culture and values of Mormonism have a way of manifesting themselves in the media they create. In this way, the fabric of American culture continues to be influenced by LDS ideals that are accepted as unconsciously and heartily as movie popcorn.

The history of Mormons in the movies is as old as the genre itself. The first feature-length documentary was One Hundred Years of Mormonism (1913). Since that time, members of the LDS Church have become increasingly involved with moviemaking at every level. In fact, they have recently developed their own industry niche (lovingly dubbed “Mollywood”). Over the past decade, movies made for a Mormon audience have become a popular, lucrative, and critically acclaimed industry.7 The movement began in earnest in 2000 with Richard Dutcher’s God’s Army, which chronicled the fictional lives of young LDS missionaries in Southern California.8

Most of LDS cinema has dealt with LDS themes and appealed to a strictly Mormon audience, poking fun at the Mormon culture and religion in a self-deprecating manner. Although the production quality is generally low, the makers of these films can count on their audience for a steady stream of DVD sales. Among the few that have ventured into mainstream tastes are Dutcher’s Brigham City (2001) and Ryan Little’s Saints and Soldiers (2003), which garnered over a dozen best picture awards on the independent film circuit.9 The filmmakers of Mormon cinema (made for Mormons, by Mormons, and about Mormons) see themselves as following the call of former Church President Spencer W. Kimball (1895–1985) who lamented once to a group at Brigham Young University that “the full story of Mormonism has never yet been written nor painted nor sculpted nor spoken.” He called on Church members to cultivate their talents and leave their inspired mark on the world (Kimball 1977: 3).

While the Mollywood movement is arguably a step in the right direction, Mormon filmography as such has yet to reach out to a broader audience and have the impact on American culture that Kimball was hoping for. This does not mean that there are no Mormons making mainstream movies, however. Many popular films have been written, produced, directed, or otherwise improved by the contributions of members of the LDS Church. In these films, there are no overtly religious overtones or other obvious indicators of LDS influence. But many do pick up on themes important to LDS values and way of life. For example, Napoleon Dynamite (2004), written and directed by Jared Hess, is full of subtle references to LDS culture, although its wide appeal made it a box-office smash and won it four “Teen Choice” awards. Hess has gone on to direct larger projects such as Nacho Libre (2006), starring Jack Black, and Gentlemen Broncos (2009). Jon Heder, who played Dynamite in 2004, has found roles as an actor in such films as The Benchwarmers with David Spade (2006), School for Scoundrels with Billy Bob Thornton (2006), Blades of Glory with Will Farrell (2007), and When in Rome with Kristen Bell (2010). Although Heder has not played a Mormon character in these films, he has brought to them a certain awkward, quirky, squeaky clean sensibility that bespeaks the LDS culture in which he was raised. Heder has also spoken openly of his faith, telling late-night talk show host George Lopez that he lives a straight-edge lifestyle, avoiding drugs, alcohol, and even caffeine.10

The influence of LDS values on mainstream movie culture is even more prevalent in animation.Don Bluth, a Mormon and graduate of BYU (like Hess and Heder), has directed, produced, or animated many of the most iconic animated films of the last century, including Sleeping Beauty (1959), The Land Before Time (1988), The Sword in the Stone (1963), Robin Hood (1973), Pete’s Dragon (1977), The Rescuers (1977), The Fox and the Hound (1981), An American Tail (1986), The Land before Time (1988), All Dogs Go to Heaven (1989), and many others. As one critic has mentioned, Bluth’s LDS upbringing has thoroughly influenced his art, just as “Woody Allen’s identity as a Jewish New Yorker is a driver of his comedy” (Barrier 2009).

Another popular animated classic that has an LDS influence is Disney’s Pinocchio (1940), whose iconic Academy Award–winning song “When You Wish upon a Star” was co-composed by Leigh Adrian Harline, who was a member of the Church. More recently, Edwin Catmull, a computer scientist, cofounded Pixar and is currently the president of Disney-Pixar animation. Catmull’s position has led to an increased collaboration between BYU and the animated film industry. According to the Deseret News, his company hires three or four BYU graduates each year, and has numerous cooperative agreements with the university’s animation and digital animation programs (Stewart 2008). The efforts of each one of these individuals have, in some respect, brought LDS values of clean living and family togetherness to an accepting American audience. Through the guise of wholesome entertainment, these films have helped to make Mormon culture a large part of American movie culture.

Countless others have made their mark on the world of film in less predictable venues. For instance, LDS filmmakers produced Schindler’s List (Jerry Molen, 1993) and The Blair Witch Project (Kevin J. Foxe, 1999). However, the overall Mormon impact on the movie industry remains inextricably connected with the same family friendly, G-rated values that define their culture. It is little wonder, then, that animation and quirky comedies have attracted the largest group of LDS film talent. It is through these sanguine and seemingly innocuous stories that the story of Mormonism, with its deep-seated, reverential belief in the American dream and values of family, sexual purity, and all-around clean living, enters the homes and psyche of millions of Americans and other viewers around the world.

Like Mormon writers in film, Glen A. Larson, creator of the television series franchise Battlestar Galactica, finds that his writing material is inspired by his personal faith (Ford 1983). For example, in both the 1978 (ABC) and 2003 (Sci-Fi Channel) series the planet Kobol is the ancient and far-away home world of humanity. For Mormons, Kolob is a celestial body identified in the Book of Abraham (3:2) as being near the home of God (Ford 1983: 85). Other instances of the Mormon influence infused into the series are the show’s governing council, the Quorum of Twelve, which parallels the LDS Church’s Quorum, and the characters’ beliefs in marriage as eternal and in the gods as more perfected humans. Simply put, the show’s plot—the search for a lost tribe and planet—and the religious beliefs that surround it, although placed in a science fiction world, are heavily borrowed from the beliefs of Mormonism.

Much like the Mormon contributions to film and appearances in television, Mormon literature can be divided into two main categories: that which appeals to Church members, and that which is written for a more mainstream audience. In the first group are the novels with LDS characters and themes, and historical studies of Joseph Smith, Brigham Young, and the Church’s pioneer heritage. These works are marketed heavily through Deseret Book, a publishing and bookselling company owned by the LDS Church.11 Deseret Book supports the mission of the LDS Church “by providing scriptures, books, music, and other quality products that strengthen individuals, families, and our society” (“About Deseret Book Company” n.d.). Most of these works are by LDS authors, written for LDS audiences, although other religious merchandise and uplifting fiction and nonfiction are also available. As a Church-owned company, Deseret Book cannot afford to let its standards slide. In 2009, “mixed review[s]” from customers led the bookseller to stop carrying Stephenie Meyer’s Twilight series in its stores (Thomas 2010). Though the books are still available through special order, the message is startlingly clear: even though Meyer is a Mormon and a graduate of BYU, and her novels are best sellers, the appropriateness of their content is not unquestionable.

With all of her recent success, Meyer presents an interesting study of the LDS writer. A faithful member of the LDS Church, she decided to write for a mainstream audience, and the mainstream accepted her wholeheartedly. Until the publication of her first book, she was a typical stay-at-home mother of three. But all of that changed quickly when Twilight (2005) debuted at number five on the New York Times “Best-Seller List.” In 2008, USA Today recognized Twilight as the best-selling novel of the year (“The Top 100 Titles of 2008” 2009). Its sequels, New Moon (2006), Eclipse (2007), and Breaking Dawn (2008), were eagerly anticipated. The final installment sold 1.3 million copies within twenty-four hours of its release (Meyer n.d.). Thanks to the success of her books, Meyer was named one of Time’s “100 Most Influential People” in 2008 (Brown and Kung 2008), and made a place for herself in Forbes’s top “100 List of the Most Powerful Celebrities” (see “The 2009 Celebrity 100” 2009).

What is remarkable is that Meyers is able to accomplish success while maintaining the value system that she states is part of her identity: she does not smoke, drink, or watch R-rated movies, and her novels lack blood, gore, and sex (although the movie adaptations of her books touch upon these themes more directly). “I don’t think my books are going to be really graphic or dark,” she said in an interview with the Times of London, “because of who I am. There’s always going to be a lot of light in my stories” (Mills 2008). As a writer for Time noted, even though Meyer does not write about Mormons, “her beliefs are key to understanding her singular talent” (Grossman 2008). Meyer’s work has become infamous for its “erotics of abstinence” and the author’s singular ability to make what is “squeaky, geeky clean on the surface,” such as hand-holding, long, lingering glances, and no sex before marriage, appeal to a mainstream audience (Grossman 2008).

While Meyer does not directly refer to Mormonism in her works, there are several Mormon themes and imagery that are interwoven in the Twilight novels. Angela Aleiss (2010) points out, for instance, that the heroine Bella avoids coffee, tea, alcohol, and tobacco, a practice parallel to the Mormon “Word of Wisdom” health code; she describes her relationship with her vampire boyfriend, Edward, as “forever,” an indirect reference to the Mormon teaching that marriages are sealed for eternity (that is, spouses are eternal companions in the afterlife and are referred to as such); the members of Edward’s family are vampires who were once human but now live without death in a resurrected condition, similar to the probationary period for eternal life that Mormons believe humans can achieve in the afterlife. There are certainly additional examples of esoteric Mormonism in Meyer’s work, suggesting again a strategy Mormons have adopted to participate in but not necessarily become a part of mainstream popular culture.

Meyer is not the only Mormon writer to gain popularity incorporating her religious morality into her fiction. Decades before Twilight, Orson Scott Card published Ender’s Game (1985) and its sequel, Speaker for the Dead (1986), both of which won top awards for writing in science fiction.12 One of Card’s characters is a non-practicing former Mormon, but there are otherwise no overt ties to his religion in the books. Still, Card admits that “Mormon beliefs and concerns crept into my work anyway, because I’m a believing Mormon and what seems true to me is always going to be more or less consonant with Mormon theology as I understand it and Mormon culture as I have experienced it” (“Orson Scott Card Interview” 2012).

Another popular Mormon author who drew on his faith for inspiration is Stephen R. Covey, whose Seven Habits of Highly Effective People (1989) has sold over 15 million copies worldwide. Covey’s explanation of what he calls “principle-based leadership” has continued to be one of the fifty best-selling titles at Amazon.com, even twenty years after its first publication. Thanks in part to this success, Covey has been named one of Time’s “25 Most Influential Americans” in 1996 and Seven Habits was named the number one most influential business book of the twentieth century (Covey n.d.). Covey was also vice-chairman and co-founder of FranklinCovey, which provides business professional services and organizational tools like day planners for individuals. Although Covey’s widespread acceptance in both the business world and the lives of private individuals (his follow-up book, The Seven Habits of Highly Effective Families, first published in 1999, has also sold more than 1 million copies) has come from a seemingly secular set of principles, Covey has acknowledged that his religion inspires and influences his work. In fact, in Divine Center (1982), a religious book written for an LDS audience, Covey urged other Mormons to “testify of gospel principles” using vocabularies that would resonate with the “experience and frame of mind” of non-Mormons (Covey 2005: 240).

According to some, this is precisely what he does in Seven Habits: testifying of his personal religious values by secularizing them and thereby making them acceptable to the mainstream. Admittedly, Mormon authors who find great success writing for the mainstream are few and far between. However, as these examples demonstrate, a number of them have reached success and touched millions of Americans who have been captivated by their winning combination of LDS values with fantastic stories or leadership strategies. Through their words, Mormon culture and values are introduced to an unwitting audience. And in many cases, that audience is more than willing to accept them. For its twentieth anniversary, FranklinCovey asked readers of its blog to share how Seven Habits had changed their lives. One respondent summed up the thoughts of dozens of other respondents by saying simply, “it changed everything” (England 2009).

The Mormon Moment?

But perhaps more important than in popular culture is the question whether the American public would be willing to accept Mormons in the national news media and politics. The answer so far appears to be yes, although whether this acceptance of Mormonism in the national media and “Mormonism” (Trepanier & Newswander), 20 politics will sustain itself remains to be seen. The two best examples of this mainstream tentative acceptance are Glenn Beck and Mitt Romney.

Glenn Beck has a large and faithful following from his popular radio program and television show, Glenn Beck (CNN, 2006-08; Fox News Channel, 2009-11).13 When on the air, Beck’s program became number one in its time slot, which included the most sought-after demographics.14 Millions of viewers tuned in weeknights to see politicians, academics, and celebrities subjected to Beck’s dogged determination to uncover truth to enlighten his viewers—a process that often includes considerable focus on his own sarcasm-laden commentary.

Further capitalizing on his media success, Beck is the author of four books that have reached number one on the New York Times “Best-Seller List.”15 Despite their unabashedly narrow ideology and unapologetic critique of the political status quo, Beck’s books have been incredibly popular. However, it is perhaps the warm-and-fuzzy short novel The Christmas Sweater (2008) that has inspired the most personal and hurtful criticism to its author. In anticipation of its success, the book was reviewed favorably by Focus on the Family, an Evangelical Christian nonprofit organization that supports socially conservative public policy. The review, by guest reporter Karla Dial, highlights Beck’s personal faith in Christ and the book’s faith-promoting message of a young boy’s struggle to learn the true meaning of Christmas. Shortly after its publication, Underground Apologetics, an evangelical Christian ministry headed by Steve McConkey, criticized Focus on the Family for promoting the writings of someone who was a member of a “false religion” and a “cult.” According to the complaint, “while Glenn’s social views are compatible with many Christian views, his beliefs in Mormonism are not” (Campbell 2008). Days later, Beck’s interview was pulled from Focus on the Family’s CitizenLink Website.16

It is not that Beck has made much attempt to hide his faith. By his own design, Beck has spoken openly on his show about his journey of redemption and atonement, which included his personal struggles to overcome alcoholism and drug abuse. By preaching that personal values and political values ought to be one and the same, Beck has mastered an especially tricky balancing act that is not often rewarded in the popular media. It is this daring combination that keeps viewers tuned into his show. Still, to anyone who was not aware of Beck’s Mormonism, it would seem that most of his principles are the same as those of mainstream conservative Christianity.

His books sell well in evangelical Christian bookstores, and apart from the scandal regarding Focus on the Family, no real controversy has arisen regarding his faith.17 But whether his Mormonism is overt or not, Beck’s unabashed infusion of religious values with political ideals has made a mark on the mainstream news media. His signature style of debate and commentary refuses to be ignored, and if ratings and book sales are any indication, millions of Americans are buying into his carefully crafted conservative-Christian-evangelical-Mormon message. And his peculiar ideology is making an impression: according to a 2009 Gallup poll, Americans consider Beck to be the fourth most-admired man alive. Positioned right between Nelson Mandela and Pope Benedict XVI (and also ahead of Billy Graham), Beck has worked his way into the esteem and won the acceptance of mainstream America in spite of his seemingly dangerous insistence on mixing politics with religion. What could be considered career suicide for many popular figures has proven to be a goldmine for Beck. His winning combination of arrogance and humility has gained him the trust and following of a slew of what he calls “real Americans.”

As some see it, Beck’s unique style—and consequently his success—comes from his affiliation with the LDS Church. For example, many of Beck’s core political values, such as an almost worshipful admiration of the American Founders and the Constitution, are deeply seated in LDS theology and did not appear in Beck’s public persona until after his conversion to the religion in 1999. Furthermore, some argue that Beck’s politics are inspired by the prominent Mormon (and staunchly conservative anticommunist) Cleon Skousen.18 The result is that the politics of Mormonism are filling the minds and ballot boxes of America—perhaps unbeknownst to Americans themselves. As one columnist wrote, “Glenn Beck marks an unprecedented national mainstreaming of a peculiar strand of religious political conservatism rooted in, and once isolated to, the Mormon culture regions of the American West” (Brooks 2009).

In other words, the political values advocated by Beck and his millions of followers across the nation are really the popular incarnation of Mormonism, born again into an easily digestible conservative form with a likable enough “pudgy, buzz-cut, weeping phenomenon” as its host (Von Drehle 2009). If the American public’s acceptance of Glenn Beck as part of the national media was relatively straightforward, it certainly was more difficult for Mitt Romney in his two runs for the presidency. The American public reservations about a Mormon president can be best summarized in a provocative exchange in 2008 between Damon Linker of the New Republic and Richard Lyman Bushman of Columbia University.

In his article, “The Big Test,” Linker describes the fundamental difference between Mormonism and mainstream Christianity as the Mormons’ belief about the vital role that the United States plays during the end times and the central place of prophecy in their religion, which precludes the possibility of philosophical reason to check its revelations (Linker 2007). Like the previous fear that a Catholic president would take orders from the Vatican, some in the American public are concerned that a Mormon president would follow his or her Church authorities or rely on his or her faith inappropriately when making political decisions. Although Linker admits that the Constitution does not require a religious test for qualification to political office, he does believe it is appropriate to ask Mitt Romney about his religious faith because Mormonism, like Islam, is a binary religion where one must accept everything or nothing. Unlike Judaism, Protestantism, or post-Vatican II Catholicism, Mormonism lacks a liberal tradition so that Mormons envision their faith not as a repository of moral wisdom but one of absolute truth. Because of this, Mitt Romney as president would have to choose whether he was first an American citizen or a Mormon believer.

Bushman defends Mormonism by citing that prophecy in the LDS Church is constrained by “the moral law [that] is enunciated endlessly in Mormon scriptures. The Ten Commandments were rehearsed in an early revelation, reinstalling them as fundamentals of the Church” (Bushman and Linker 2007). New revelations would not be able to call for acts of violence if so prophesied, since they would be restrained by previous revelations that are considered fundamental to the LDS Church’s theology. According to Bushman, the fact that prophecy operates within the framework of this older revelation is an adequate safeguard that prevents its abuse. It is analogous to how the Supreme Court decides cases within the framework of the Constitution: the prophet’s authority depends on reasoning from past revelations as well as from all past decisions.

Romney addressed the subject directly in a speech entitled “Faith in America” on December 6, 2007, at the George Herbert Walker Bush Presidential Library (see Romney 2007). Modeled after John F. Kennedy’s September, 1960, pledge not to allow Catholic doctrine to inform U.S. policy (see Kennedy 1960), Romney’s speech made the same pledge but this time with reference to Mormonism. Although Romney declined to address the specifics of his religious faith except that the LDS “church’s beliefs about Christ may not all be the same as those of other faiths,” he did advocate a separation of church and state and declared that he would decline directives from churches, including the LDS Church, if elected president. The speech was widely praised by political commentators, although it did little to help Romney in the Iowa caucus where an estimated 40% of the Republican electorate identified themselves as evangelical Christians (see Conger 2010).

In spite of his failure in 2008 Republican presidential nomination contest, Mitt Romney secured the nomination of his party in 2012. Republican leaders, who worry that anti-Mormon views were prevalent among the public, and especially among evangelical Christians who form a sizable part of the party’s base, worked to dispel the religious stigma. For example, former Arkansas Governor and Baptist minister Mike Huckabee, in an address before the Republican National Convention in Tampa, declared that he cares “far less” about where Romney goes to church than about where he would take the country; and Paul Ryan, the Republican vice-president nominee and Catholic, noted that he and Romney go to “different churches” yet share the “same moral creed” (Davis 2012).

On the night of Romney’s acceptance of his party’s nomination for president, there were several heartfelt testimonies of Romney’s friends who spoke directly about the candidate’s religious faith and how it has formed his moral views. Fellow Mormons Ted and Pat Oparowski and Pam Finlayson spoke of Romney’s help and kindness to their families as they dealt with tragedies in their lives. As a bishop of the LDS Church, Romney became stake president, the highest Mormon authority in his region, and oversaw several congregations in a district similar to a diocese. He counseled LDS members on their most personal concerns, such as marriage, parenting, and faith, and worked with immigrant converts from other countries. Grant Bennett, an assistant to Romney at their congregation, told Republican delegates that Romney had “a listening ear and a helping hand,” devoting as many as twenty hours a week as stake president (Zoll 2012).

In his acceptance speech at the Republican National Convention, Romney recalled growing up as one of the few Mormons in Michigan but portrayed it as any other type of mainstream Christian faith: “We were Mormons and growing up in Michigan; that might have seemed unusual or out of place but I don’t remember it that way. My friends care more about what sports team we followed than what church we went to” (Romney 2012). Romney also referred to his faith when his family moved to Massachusetts and joined the LDS Church there: “We had remarkably vibrant and diverse congregants from all walks of life and many who were new to America. We prayed together, our kids played together and we always stood ready to help each other out in different ways.”

Romney’s oblique references to his Mormonism throughout his campaign for the presidency is a prudential strategy, as 18% of the American public say they would not vote for a Mormon for president, a figure largely unchanged since 1967 (Jones 2012). Only atheists (43%) and Muslims (40%) score higher than Mormons when Americans are asked the question whether they would be unwilling to vote for “a well-qualified person for president who happened to be.” By comparison, the American public’s reservations for voting a Catholic or Jew (as well as for a woman, black, or Hispanic) for president are less than 7%. In short, there exists a well-entrenched minority of Americans who continue to view Mormonism suspiciously, especially when Mormons run for national political office.

This reservation is not a surprise to most Mormons, with six in ten Mormons (62%) saying that the American public as a whole are uninformed about their religion and nearly half (46%) state they face discrimination in the U.S. today, a percentage that is higher than blacks (31%) and atheists (13%). Two thirds (68%) state that Americans as a whole do not see Mormonism as part of mainstream America; and 56% of Mormons cite misperceptions about their religion, discrimination, and lack of acceptance in American society as the most important problems facing Mormons living in America. With respect to the way their religion is portrayed in television and movies, 54% of Mormons believe the depiction of their religion hurts society’s image of them. However, Mormons are less negative in their assessment of the news media’s treatment of Mormonism, with about half (52%) saying that coverage of Mormons and Mormonism by American news organization is generally fair, although a significant minority (38%) believe the news coverage of Mormonism to be unfair (see Pew Forum on Religion and Public Life 2012).

Conclusion

Speaking esoterically about one’s faith—whether in television, movies, literature, or political ideology—has a firm foundation in the Mormon experience. Given their history of conflict, persecution, and exile, Mormons are justified in being wary when entering mainstream American society. They must balance making their religious beliefs accessible and familiar and not succumbing to secular values. To mainstream America, the message is that Mormons share the same conservative and religious values that other people do, while to Mormons what is conveyed is that one’s principles and beliefs are not compromised. For Mormons, this is a legitimate way to navigate a pluralist society in order to gain mainstream acceptance; for its critics, this is nothing more than equivocation and clever hedging.

This esoteric strategy is required because of the American public’s unease with the perceived duality of Mormonism: its all-American and wholesome values and its seemingly strange and secretive practices. However, as religious minorities attain a certain size or significance, they become part of the mainstream culture and begin to be portrayed accurately in movies, television shows, literature, and the news media, though some stereotypes persist. The experience of the Mormons is no different in this respect. As Mormons have become more prevalent and open about their beliefs in mainstream American popular culture, anti-Mormon sentiment and expression have abated, promising a possibly more harmonious relationship between Mormon and mainstream culture.

In this sense, Mormons reveal inherent tensions in mainstream American popular culture. Americans seem to want the all-American values of Donny & Marie as well as the strange and the bizarre of Big Love. Mormons are ideal candidates for this dual role: they are a minority and are known but not well understood. They represent values that Americans admire, although their religion historically has been portrayed negatively. Thus, the portrayal of Mormons in the mainstream media as representing both exaggerated normalcy and oddity would seem to be a manifestation of American popular culture. That is, the political and cultural debates about liberal and secular versus conservative and religious; the admiration for material success and clean living combined with a fascination for the strange and secretive; and the affirmation of American values along with a constant critique of them constitute the essence of mainstream American popular culture, and these tensions have been manifested by various minority groups throughout America’s history.

Works Cited

“About Deseret Book Company” (n.d.) Deseret Book. Online. Available HTTP: <http://deseretbook.com/pages/about> (accessed 23 September 2012).

Aleiss, A. (2010) “Mormon influence, imagery run deep through ‘Twilight,’” Huffington Post (June 24). Online. Available HTTP: <http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2010/06/24/mormon-influenceimagery_

n_623487.html> (accessed 17 October 2012).

Atkinson, S. (2008) “America’s next top Mormon, reality-tv shows are plucking contestants from an unlikely pew,” Newsweek (May 19): 52.

Barrier, M. (2009) “Bluth talk,” Michael Barrier.com [blog] (April 6). Online. Available HTTP: <http://www.michaelbarrier.com/Home%20Page/WhatsNewArchivesApril09.htm#bluthtalk> (accessed 23 September 2012).

Beck, G. (2003) The Real America: Messages from the Heart and Heartland, New York: Pocket Books.

—. (2008a) The Christmas Sweater, New York: Threshold Editions.

—. (2008b) An Unlikely Mormon: The Conversion Story of Glenn Beck [sound recording]. Salt Lake City: Deseret Book.

—. (2009a) “Glenn Beck story pulled because of his Mormon faith,” Glenn Beck (January 4). Online. Available HTTP: <http://www.glennbeck.com/content/articles/article/200/19594/> (accessed 23 September 2012).

—. (2009b) Arguing with Idiots: How to Stop Small Minds and Big Government, New York: Threshold Editions.

—. (2009c) The Christmas Sweater: A Picture Book, New York: Aladdin / Mercury Radio Arts.

—. (2009d) Glenn Beck’s Common Sense: The Case Against an Out-of-control Government [sound recording], New York: Simon & Schuster Audio.

—, and Kevin Balfe (2007) An Inconvenient Book: Real Solutions to the World’s Biggest Problems, New York: Threshold Editions.

Brooks, J. (2009) “How Mormonism built Glenn Beck,” Religion Dispatches (October 27). Online. Available HTTP:

<http://www.religiondispatches.org/archive/religiousright/1885/how_mormonism_built_

glenn_beck?page=entire> (accessed 23 September 2012).

Brown, S., and M. Kung. (2008) “The 2008 Time 100 finalists,” Time (April 1). Online. Available HTTP:

<http://www.time.com/time/specials/2007/article/0,28804,1725112_1726934_1726935,00.html> (accessed 23 September 2012).

Burgess, S. (1999) “Donny Osmond: we suffer for his art,” Salon.com (September 21). Online. Available HTTP:

<http://www.salon.com/people/feature/1999/09/21/osmond/index.html> (accessed 23 September 2012).

Bushman, R.L. (1984) Joseph Smith and the Beginnings of Mormonism, Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press.

—, and D. Linker (2007) “Mitt Romney’s Mormonism: a TNR online debate.” New Republic (January 3). Online. Available HTTP: <http://www.tnr.com/article/politics/mitt-romneysmormonism#Bushman1> (accessed 23 September 2012).

Campbell, J. (2008) “Focus on Family pulls Glenn Beck article,” Deseret News (December 27). Online. Available HTTP: <http://www.deseretnews.com/article/705383058/Focus-on-Family-pulls-Glenn-Beck-article.html?pg=all> (accessed 23 September 2012).

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (2006) “Church responds to questions on TV series,” The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints: Newsroom (March 6). Online. Available HTTP: <http://newsroom.lds.org/ldsnewsroom/eng/commentary/churchresponds-to-questions-on-hbo-s-big-love> (accessed 23 September 2012).

—. (2009) “The publicity dilemma,” The Church of Jesus Christ of the Latter-Day Saints: Newsroom (March 9). Online. Available HTTP:<http://newsroom.lds.org/ldsnewsroom/eng/commentary/the-publicity-dilemma>(accessed 11 October 2012).

Conger, K.H. (2010) “Evangelicals, issues, and the 2008 Iowa caucuses,” Politics and Religion 3: 130-149.

Covey, S.R. (2005) The Divine Center, Salt Lake City: Deseret Book.

—. (n.d.) “About Stephen R. Covey,” StephenCovey.com. Online. Available HTTP: <http://www.stephencovey.com/about/about.php> (accessed 23 September 2012).

Davis, J.H. (2012) “Romney speaks of Mormon faith to try to dispel prejudice,” Bloomberg News (August 30). Online. Available HTTP: <http://www.businessweek.com/news/2012-08-30/romney-speaks-of-mormon-faith-to-try-to-dispel-prejudice> (accessed 23 September 2012).

“Donny Osmond” (2004) BBC News (December 6). Online. Available HTTP: <http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/programmes/hardtalk/4054629.stm> (accessed 23 September 2012).

Dutcher, R. (2007) “Richard Dutcher: ‘parting words’ on Mormon movies,” (Provo, Utah) Daily Herald (April 11): A6.

England, B. (2009) “Share with us how the 7 habits has changed your life,” FranklinCovey Blog (March 6). Online. Available HTTP: <http://www.franklincovey.com/blog/20thanniversary-7-habits-highly-effective-people.html> (accessed 23 September 2012).

Evans, S. (2006) “South Park Mormonism,” By Common Consent [blog](June 3). Online. Available HTTP: <http://bycommonconsent.com/2006/06/03/south-park-mormonism/> (accessed 23 September 2012).

Ford, J.E. (1983) “Battlestar Galactica and Mormon Theology,” Journal of Popular Culture 17, 2 (Fall): 83-87.

Grossman, L. (2008) “Stephenie Meyer: a new J. K. Rowling?” Time (April 24). Online. Available HTTP:

<http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,1734838,00.html#ixzz0gT11bdmP> (accessed 23 September 2012).

Havrilesky, H. (2006) “I like to watch,” Salon.com (March 5). Online. Available HTTP: <http://www.salon.com/2006/03/05/big_love_4/> (accessed 23 September 2012).

Hicks, C. (2005) “TV portrayal of Mormons mean, callous,” Deseret News (May 6). Online. Available HTTP: <http://www.deseretnews.com/article/1,5143,600131613,00.html> (accessed 23 September 2012).

“Inside the Lives of a Polygamist Family” (2010) Oprah.com (October 14). Online. Available HTTP: <http://www.oprah.com/oprahshow/Inside-the-Lives-of-a-Polygamist-Family/1> (accessed 23 September 2012).

Jennings, K. (2006) “About Ken,” Ken Jennings: Confessions of a Trivial Mind. Online. Available HTTP: <http://www.ken-jennings.com/aboutken.html> (accessed 23 September 2012).

—. (2007) “Politicians and pundits, please stop slandering my Mormon faith,” (New York) Daily News (December 18). Online. Available HTTP: <http://www.nydailynews.com/opinion/politicians-pundits-stop-slandering-mormonfaith-article-1.272933> (accessed 20 September 2012).

Jones, J.M. (2012) “Atheist, Muslims see most bias as presidential candidates,” Gallup (June 12). Online. Available HTTP: <http://www.gallup.com/poll/155285/Atheists-Muslims-Bias-Presidential-Candidates.aspx> (accessed 23 September 2012).

Kennedy, J.F. (1960) “Address of Senator John F. Kennedy to the Greater Houston Ministerial Association, September 12, 1960,” John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum. Online. Available HTTP: <http://www.jfklibrary.org/Asset-Viewer/ALL6YEBJMEKYGMCntnSCvg.aspx> (accessed 17 October 2012).

Kimball, S. (1977) “First Presidency message: the gospel vision of the arts,” Ensign (July): 3.

King, S. (2007) “Television impaired,” Entertainment Weekly (January 26): 80.

Kirkland, L. (2011) “Book of Mormon musical: Church’s official statement” The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints: The Newsroom Blog (February 7). Online. Available HTTP:<http://www.mormonnewsroom.org/article/church-statement-regarding-the-book-ofmormon-broadway-musical> (accessed 23 September 2012).

Linker, D. (2007) “The big test: taking Mormonism seriously,” New Republic (January 15). Online. Available HTTP: <http://www.tnr.com/article/politics/the-big-test> (accessed 23 September 2012).

Meyer, S. (n.d.) “Bio,” The Official Website of Stephenie Meyer. Online. Available HTTP: <http://www.stepheniemeyer.com/bio.html> (accessed 23 September 2012).

Mills, T. (2008) “Her vampire’s right behind you, JK; interview: Stephenie Meyer,” (London) Sunday Times (August 10): News Review 5.

“Orson Scott Card Interview” (2012) Hatrack River: The Official Web Site of Orson Scott Card. Online. Available HTTP: <http://www.hatrack.com/research/interviews/interview.shtml> (accessed 23 September 2012).

Otterson, M. (2011) “A Latter-Day Saint view of Book of Mormon Musical,” Washington Post (April 14). Online. Available HTTP: <http://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/onfaith/post/why-i-wont-be-seeing-the-book-of-mormonmusical/2011/04/14/AFiEn1fD_blog.html> (accessed 23 September 2012).

Pew Forum on Religion and Public Life (2012) “Mormons in America: certain in their beliefs, uncertain of their place in society” (January 12). Online. Available HTTP: <http://www.pewforum.org/Christian/Mormon/mormons-in-america-executivesummary. aspx> (accessed 23 September 2012).

Poniewozik, J. (2007) “Top 10 Returning TV Series,” Time (December 9). Online. Available HTTP: <http://www.time.com/time/specials/2007/article/0,28804,1686204_1686244_1691404,00.html? (accessed 23 September 2012).

Romney, M. (2007) “Transcript: Mitt Romney’s faith speech,” National Public Radio (December 6). Online. Available HTTP: <http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=16969460> (accessed 23 September 2012).

—. (2012) “Transcript: Mitt Romney’s acceptance speech.” National Public Radio (August 30, 2012): www.npr.org/2012/08/30/160357612/transcript-mitt-romneys-acceptance-speech (accessed September 23, 2012).

Ryan, M. (2006) “It’s hard out here for a polygamist: ‘Big Love,’” Chicago Tribune (March 9). Online. Available HTTP: <http://featuresblogs.chicagotribune.com/entertainment_tv/2006/03/its_hard_out_he.html> (accessed 23 September 2012).

Shipps, J. (1985) Mormonism: The Story of a Religious Tradition, Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press.

Stelter, B. (2012) “Beck is taking his conservative internet shows to the Dish Network,” New York Times (September 12): B1, 4.

Stewart, A.K. (2008) “BYU center to develop animation creations,” Deseret News (March 28). Online. Available HTTP:<http://www.deseretnews.com/article/1,5143,695265400,00.html> (accessed 1 April 2010).

Thomas, E. (2009) “‘Twilight’ loses luster with Deseret Book,” Deseret News (April 23). Online. Avaliable HTTP: <http://www.deseretnews.com/article/705299108/Twilight-loses-lusterwith-Deseret-Book.html> (accessed 1 April 2010).

“The Top 100 Titles of 2008” (2009) USA Today (January 15): 5D.

“The 2009 Celebrity 100” (2009) Forbes (June 3). Online. Available HTTP: <http://www.forbes.com/lists/2009/53/celebrity-09_Stephenie-Meyer_NORR.html> (accessed 23 September 2012).

Von Drehle, D. (2009) “Mad man: is Glenn Beck bad for America?” Time (September 17). Online. Available HTTP:

<http://www.time.com/time/politics/article/0,8599,1924348,00.html> (accessed 23 September 2012).

Wilson, B. (2006) “LDS Church rejects polygamous accusations,” Deseret News (February 28). Online. Available HTTP: <http://www.deseretnews.com/article/1,5143,635188091,00.html> (accessed 23 September 2012).

Zoll, R. (2012) “Romney makes Mormonism part of his big night,” US News and World Report (August 31). Online. Available HTTP: <http://www.usnews.com/news/politics/articles/2012/08/31/romney-makes-mormonismpart-of-his-big-night> (accessed 23 September 2012).

Notes

1 A common non-Mormon misconception is that being a Mormon is the same as being a member of the LDS Church. In reality, while all members of the LDS Church are Mormons, not all Mormons are members of the LDS Church. The LDS Church is certainly the largest, but by no means the only Mormon denomination (see Shipps 1985: x, xii, xv, 21).

2 For more about Donny’s professional career, see “Donny.com” (www.donny.com/).

3 In the interview, Michael Jackson suggests to Donny Osmond that he change his name because it is considered too wholesome.

4 This is not to equate the violence Mormons suffered with the prejudicial that treatment homosexuals experience, but rather to show the similarities in how two minority groups were treated by the majority of Americans. For more about violence against Mormons, see Shipps 1985, 155-61.

5 For more about these participants, see the Survivor Web site: www.cbs.com/primetime/survivor/.

6 In fact, she was so popular that she was invited to appear in two episodes of MTV’s reality show Road Rules.

7 They even have their own annual LDS Film Festival.

8 Interestingly, Dutcher is no longer a practicing Mormon and no longer makes Mormon films. He announced his departure from the faith and his lament over the current state of Mormon filmmaking in an open letter published in the Provo Daily Herald. He also stated his lingering hope: “Wouldn’t it be amazing,” he said, “if the Mormon community did what nobody else in the world seems interested in doing: exploring human spirituality, human truth in film. Expand the vocabulary of film, learn to do things on the broad white canvas of a movie screen that no one has yet imagined” (Dutcher 2007).

9 Information provided at the film’s Web site Saints and Soldiers (saintsandsoldiers.com/).

10 The interviewed aired on Lopez Tonight (TBS), February 2, 2010. These are markers of a faithful LDS lifestyle.

11 Because Deseret Book is a for-profit company privately owned by the LDS Church, no sales figures are made available to the public.

12 The Nebula Award (1985–86) and the Hugo Award (1986–87). Never before nor since have the awards been given to the same author in two consecutive years.

13 Beck returned to television after the success of his Internet-only television show, The Blaze TV. The show has been picked up by Dish Network (see Stelter 2012).

14 Beck’s show first hit number one in the ratings in September, 2009, and has consistently been among the three highest-rated cable news shows.

15 An Inconvenient Book (2007), The Christmas Sweater (2008), Arguing with Idiots (2009), and a children’s picture version of The Christmas Sweater (2009). Beck is also the author of The Real America (2003) and Glenn Beck’s Common Sense: The Case Against an Out-of-control Government (2009).

16 In response to this controversy, Beck posted a “special commentary” on his Web site, pleading for religious tolerance: “At a time when the world is so full of fear, despair, and divisions, it is my hope that all of those who believe in a loving and peaceful God would stand together on the universal message of hope and forgiveness” (Beck 2009a).

17 Some would argue that this is because Beck does not promote his Mormonism openly. For instance, a DVD produced by LDS-affiliated Deseret Book titled Glenn Beck: An Unlikely Mormon is not advertised on his Web site. Of course, there are detractors. Notable among them is Stephen King, who referred to Beck as “Satan’s mentally challenged younger brother” (King 2007).

18 Beck cites Skousen in The Real America (2003) and has promoted his work on the air.

This was originally presented at the Mormonism in Cultural Context Symposium at the Springville Art Museum in Springville, Utah on June 18, 2011. Portions of this was incorporated in the first chapter of LDS in USA: Mormonism and the Making of Mormon Culture (Baylor University Press, 2012). See our review of it as well as How Mormonism Shaped America,” “An American Marriage: Mormons, Polygamy, and Federalism.” “Liberal Democracy and Mormon Culture,” “Mormon Authority and Identity in America,” and “The Transformation From Theocracy to Democracy in Utah.”