Murder Most Foul and America’s Soul (Part II)

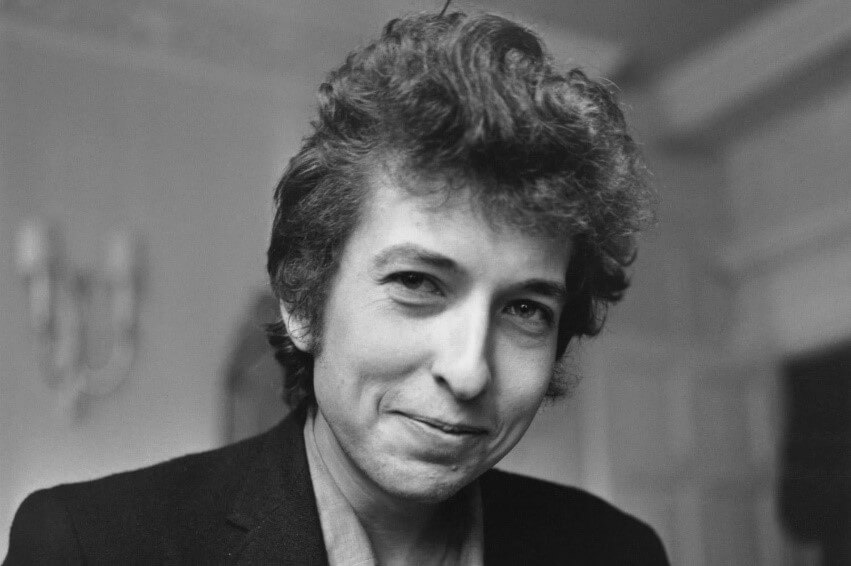

In our previous essay, we looked at Bob Dylan with an emphasis on his qualities as a timeless moral leader and musician. Now, we shall consider his great literary merits with greater emphasis.

For the Love of Language and Literature

After a long career filled with lyrical genius and paying homage to the great poets and writers through the ages, Dylan was finally awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 2016. [59]

This is especially sweet against the row of desolation we mentioned before, and within the scandalous study and practice of what passes for ‘literature’ today. The great artforms into which Dylan has stepped, music and literature, have each been brought to their knees by political idolatry. Several ‘theories’ serve powers and dominions not much different from the false gods of old:

Benjamin Lockerd decries the desecration of the great arts:

‘What these newer theories have in common is that they have taken the capital T away from truth and transferred it to Theory.

They are either materialist (Marx and Freud) or relativist (deconstructionist) or political (feminist, post-colonial), but they all assume that the ancestors were wrong and vicious and must be ignored or denounced. And they are all dedicated to abolishing the canon (the list of what we used to call great authors).’ [60]

The rebellion against the real has become very technical and created turgid new vernacular to worship with.

In sync with Lockerd, Eric Voegelin has rightly contended that, ‘The occupation with works of art, poetry, philosophy, mythical imagination and so forth, makes sense only if it is conducted as an inquiry into the nature of Man.’

Reminding us that ‘To be open to the gifts of literature, we must attend to her with love and wisdom. This is a far cry from the reductionist hubris of the social ‘sciences’ noted above.’ [61]

For the ideologue without a true center, there is only power, and arbitrary centers of ‘meaning’ which should be desecrated with ceaseless revolutions. Like the revolutions of a Ferris wheel, this carnival of chaos can make Man very dizzy indeed.

Not many would have known how far Nobel Prize-Winning Dylan would come when he stepped onto stage at The Newport Folk Festival of 1964, to wow the crowd after an introduction by folk stalwart Pete Seeger.

But when we watch that magical performance and hear something unique like Mr Tambourine Man it is really no surprise:

‘Though I know that evening’s empire has returned into sand

Vanished from my hand

Left me blindly here to stand but still not sleeping

My weariness amazes me, I’m branded on my feet

I have no one to meet

And the ancient empty street’s too dead for dreaming

Hey! Mr. Tambourine man, play a song for me

I’m not sleepy and there is no place I’m going to

Hey! Mr. Tambourine man, play a song for me

In the jingle jangle morning I’ll come following you

Take me on a trip upon your magic swirling ship

My senses have been stripped

My hands can’t feel to grip

My toes too numb to step

Wait only for my boot heels to be wandering

I’m ready to go anywhere, I’m ready for to fade

Into my own parade

Cast your dancing spell my way, I promise to go under it.’ (Mr Tambourine Man) [62]

Embry commends our wiser artistic statesmen who live with love at the center of their concerns and place us under their ‘dancing spell’ again.

The critic must be moved out of their detached complacency to judge art and the artist justly. This can only be achieved by returning to love:

‘For a literary critic to be first and foremost a philosopher would appear to be a formidable qualification, but in returning to the Platonic understanding of that term — as Voegelin did — we find that a philosopher need only be a lover of wisdom. This is a very important understanding of the term philosopher, because it places the accent on lover without forcing a definition of wisdom.’ [63]

To echo Abraham Joshua Heschel, ‘Wonder rather than doubt is the root of knowledge.’ [64]

We recover childlike wisdom when we stand before the best ancient artists and moral forces with due respect, learning from those who prop up the lasting edifice of beauty, goodness and truth. We are reminded of the cornerstones of true civilization and the type of eternal questions that have filled Bob Dylan’s longing ballads. Those questions of The Spirit that ‘blow in the wind’.

Embry argues that, ‘The philosophical search in which a lover of wisdom engages is fundamentally Socratic, characterized by an essential humility and knowing ignorance, which requires the philosopher to recognize that for human beings there can be no final, complete knowledge of wisdom.’ [65]

‘A self-ordained professor’s tongue

Too serious to fool

Spouted out that liberty

Is just equality in school

“Equality,” I spoke the word

As if a wedding vow.

Ah, but I was so much older then

I’m younger than that now.’ (My Back Pages)

‘You lose yourself, you reappear

You suddenly find you got nothing to fear

Alone you stand with nobody near

When a trembling distant voice, unclear

Startles your sleeping ears to hear

That somebody thinks they really found you, it’s alright ma.’ (It’s Alright Ma) [66]

After a startling rise to the heights of American music in the early sixties, Dylan was held to be a demi-god who could do no wrong. The fans were eager for a new idol to worship and made use of Dylan for their purposes.

That was until 1965, when Dylan became their ‘Judas’ because he ‘went electric’ and shocked folk to the core. At the time of this public divorce with fans he was getting married to Sara and beginning a new life.

Idols of power, and what should really be marginal identities, take center stage in the passionless play of the present age. In a new form of an old problem, Tim Keller describes these counterfeit gods:

‘Our hearts are idol-making factories that make good gifts from God ultimate in our lives, thereby replacing God in our affections.’ [67] Before he asks one of those eternal questions we mentioned before. Like Dylan, he sees nowhere to turn but towards the authority of The Spirit:

‘And there’s no exit in any direction

’Cept the one that you can’t see with your eyes. (Series of Dreams) [68]

Keller asks, “What is an idol?’ Deciding that, ‘It is anything more important to you than God, anything that absorbs your heart and imagination more than God, anything you seek to give you what only God can give.”

Keller then wonders, ‘How can you identify these insidious idols? How can you tell if you are worshipping a counterfeit God?’

He ends up giving us a beautiful concise answer that should help us re-center on what really matters. “A counterfeit god is anything so central and essential to your life that, should you lose it, your life would feel hardly worth living.” [69]

Who or what do we ‘need’ and what ‘must’ we have?

‘They say ev’ry man needs protection

They say ev’ry man must fall

Yet I swear I see my reflection

Some place so high above this wall

I see my light come shining

From the west unto the east

Any day now, any day now

I shall be released.’ (I Shall be Released) [70]

Bondage under Pharaoh

‘They lowered him down as a king

But when the shadowy sun sets on the one

That fired the gun

He’ll see by his grave

On the stone that remains

Carved next to his name

His epitaph plain

Only a pawn in their game.’ (Only a Pawn in Their Game) [71]

As you may have noticed from the last few passages, idols demand churches and just like the Israelites who bowed in worship before the golden calf, ‘enlightened modern people’ will gather in the name of ‘progress’ or ‘equality’, just as easy.

Canadian Philosopher James KA Smith cautions against these ‘secular liturgies’ which worship (give ultimate worth to) chosen gods of this world. By reminding us we are primarily worshipping creatures, he makes it easier to discern false gods that demand our time and sacrifices.

He argues, ‘…forms are not neutral. Indeed, that was one of the core arguments of the first volume, Desiring the Kingdom.’ (In a series of books on Cultural Liturgies)

Before contending persuasively, ‘Cultural practices that we might think are “neutral” – just something that we do – are actually doing something to us. They are formative. But what they form is our heart-habits, our loves and longings that… actually drive our action and behavior.’ [72]

This points to the importance of musical icons like Dylan. A true icon points beyond itself to something more and is not meant to be worshipped like an idol. Dylan points to the music, the stories and The Scriptures to fight the idols of infatuation. ‘It aint me you’re lookin’ for babe.’ [73]

Amidst fervent secularist worship lies a desire for earned righteousness that pressures the believer to be on ‘the right side of history.’ Again, one-time right-wing idolater Joseph Pearce had his heart changed by the power of Truth in history.

Pearce mirrors Dylan’s prophetic pronouncements and historical humility here:

‘Those who treat the past with contempt, refusing to learn its lessons and worshipping the imaginary machine of “progress,” will be the tools of tyranny today as they have been the tools of tyranny in the past. They are not only on the wrong side of history; they are on the wrong side of humanity…’ [74]

The progressive spirit of the sixties already seemed like an illusion to Dylan by the seventies, jaded by politics, romantic separation and the dark side of drugs, he knew that life isn’t ‘black and white’ as if he’d seen it in a dream. This was the ‘thorny crown’.

‘As easy it was to tell black from white

It was all that easy to tell wrong from right

And our choices they was few so the thought never hit

That the one road we traveled would ever shatter and split.’ (Bob Dylan’s Dream) [75]

Nowhere is this expressed more beautifully than in Dylan’s disturbing With God on our Side. Despite his rightful scorn directed at those who labelled him Judas Iscariot for musical ‘betrayal’, he knows that we all have some Judas Iscariot in us and has kept that in mind to create some of the most profound moral ballads in the history of music.

Like Solzhenitsyn on the Russian side, Bob was afraid of America losing her soul by Man making her an idol. Solzhenitsyn and this descendent of immigrants from Odessa both knew that ‘The line between good and evil cuts across every human heart.’ [76]

This is an essential and timeless truth that kept Dylan’s conscience clear during the moral haze of the Cold War and continues to set a moral pulse for his art.

In his music, Dylan was asking questions about American identity and what it meant to be truly human. Were they really on the ‘right side of history?’ Is there an obvious ‘right side of history’?

Dylan, like the prophets before him, calls us to think again about who or what we are willing to offer sacrifices.

‘…I’ve learned to hate the Russians

All through my whole life

If another war comes

It’s them we must fight

To hate them and fear them

To run and to hide

And accept it all bravely

With God on my side

But now we got weapons

Of chemical dust

If fire them we’re forced to

Then fire them we must

One push of the button

And a shot the world wide

And ya’ never ask questions

When God’s on your side

Through many dark hour

I been thinking about this

That Jesus Christ

Was betrayed by a kiss

But I can’t think for ya’

You’ll have to decide

Whether Judas Iscariot

Had God on his side.’ (With God on Our Side) [77]

The Jester and the King

Many of us living through the crisis of Covid-19 find ourselves in unfamiliar territory. We millennials and younger generations have not lived through the same kind of testing times as the boomer generation, upon whom some have poured much scorn.

Now that we aren’t okay, it might be time to listen to some of those boomers who have lived through trials like this before. They have at least felt the freezing chill of The Cold War and spent many long dark nights not knowing what the morning would bring.

The Dylan of Murder Most Foul has been around the world and back and has seen a thing or two worthwhile. Much of which is still unknown. Between the heady days of the sixties and Dylan’s musical rebirth decades later, he remained a still small voice dedicated to plumbing the riches of tradition.

His later inspired albums such as Tempest and Modern Times, with their many creative references to Ovid, Shakespeare, tragedy and salvation, might not have taken place without a quiet return home. These mature works may even be the works from which we can learn the most. Dylan can show us how to grow old gracefully, deepen artistically and live morally.

At least this special boomer might serve as a model for us. Whilst we are now physically bound to home again and have been given time to reframe what is worth living and dying for, this growing icon can point a way forward.

Sean Wilentz kept faith in Dylan’s important artistic and moral importance even during those days when Dylan went into the wilderness. He believed he would ‘find his muse again’. [78] By returning home again, in body and spirit, and with the help of a good guide we might find ours too.

Don McLean’s American Pie plays the long game of American music history to show just a fraction of Dylan’s seminal role:

‘When the jester sang for the king and queen

In a coat he borrowed from James Dean

And a voice that came from you and me

Oh and while the king was looking down

The jester stole his thorny crown

The courtroom was adjourned

No verdict was returned.’ (American Pie) [79]

In Don McLean’s song, we discover a jester long held to be Dylan. ‘Bob Dylan is the most likely candidate for a number of reasons. Including the fact that Dylan donned a windbreaker jacket like the one worn by James Dean in ‘Rebel Without a Cause’. This featured on the cover of his early ‘Freewheelin’ album. [80]

Polyphonic’s excellent short YouTube video on this popular song describes, ‘the jester on the sidelines in a cast’. Supposedly referring to Dylan’s motorbike accident, which left him injured and ailing for months. Bob was the jester who took over the throne from Elvis, only to find a ’crown of thorns’. [81]

This early history is well known and covered. And the later 1975 Blood on the Tracks is widely heralded as one of the greatest albums ever. [82] Yet, some of Dylan’s greatest work has come later and is unknown to all but serious Dylan fans.

Bob’s cold response to the cultish fever surrounding him in those days and later Christian conversion may have cost him many fans and turned much of the public off. He won’t complain, but it means that many don’t know the story since.

Yes, Dylan saw through attempts to make him ‘the voice of a generation’ from these early days and passed on the cup of national idolatry, but that’s because his eyes were cast higher. We should follow his ascent up the mountain from those early days to the clear heights of Murder Most Foul.

This playful jester, or trickster, role in Dylan goes far beyond the confines of the sixties however and has shown its non-orderly hand over Dylan’s long oeuvre.

The song Jokerman is a clear example. Whilst Dylan’s ‘The Man in Me’ was the song chosen for The Coen Brother’s cult classic The Big Lebowski, Jokerman best reflects the spirit of the movie. This complex song serves as a ‘carnivalesque critique of society’ by calling out lies, pernicious politics and a whole series of laughable self-deceptions. [83]

‘You’re a man of the mountains, you can walk on the clouds

Manipulator of crowds, you’re a dream twister

You’re going to Sodom and Gomorrah

But what do you care? Ain’t nobody there would want marry your sister

Friend to the martyr, a friend to the woman of shame

You look into the fiery furnace, see the rich man without any name.’(Jokerman) [84]

Dylan did not savor a savior complex nor seek out counterfeit godhood but longed instead to expose the presupposed pretensions of what Jacques Ellul named ‘world opinion’. [85]

The early halakhic influences of his youth have found new wine skins, under the influence of Yeshua, the ‘cosmic joker’ who inspired his criticisms of false gods and prophets. This is still a scandal and foolishness to fallen Man. [86] The ‘Gospel Period’ of the late seventies and early eighties was only the beginning of a long period of rich songs alluding to The Bible and its answers to Man’s greatest questions. This has been covered in marvelous books by Scott Marshall, Phil Mason and others. This quieter but profound later spiritual period has also seen Dylan make ingenious plays on the work of Shakespeare, the ancient Mediterranean poets and classics of world literature. [87]

Let’s briefly compare Shakespeare and Dylan:

‘Both are literary magpies. Dylan reworked the folk song No More Auction Block as Blowing in the Wind and he took the tune from Scarborough Fair for Don’t Think Twice It’s Alright. Shakespeare dusted down old history plays and turned them into riveting political dramas such as Richard III and Henry V. He also turned an old play about King Leir into one of his most powerful tragedies and remade Thomas Kyd’s revenge play Hamlet into one of the greatest works in literature. These are not isolated examples: almost everything Shakespeare and Dylan wrote has a source which they adapted.’

This comparison by Stuart Hampton-Reeves is enlightening. He goes on to tell us that, ‘Between them, Dylan and Shakespeare are probably the two greatest thieves in literature – but they always made the material better, their versions often superseding and obliterating what went before.

But the similarities do not end there, for few writers have elevated the common insult to high art as Shakespeare and Dylan. Dylan is famously unforgiving in his songs, many of which are caustic character assassinations. Take for example this unforgettable putdown from Positively Fourth Street (1964):

Yes, I wish that for just one time you could stand inside my shoes. You’d know what a drag it is to see you… But no one insults like Shakespeare. Try this from Henry IV Part One: “Thou clay-brained guts, thou knotty-pated fool, thou whoreson obscene greasy tallow-catch!” Or this, from As You Like It: “Your brain is as dry as the remainder biscuit after voyage.”

Both master the written word and put it to good use, whether through transcendent meditations or comical curses.

Hampton-Reeves says, ‘To my knowledge, Dylan has never written any plays, but characters from Shakespeare crop up in many of his songs. Ophelia appears in Desolation Row (1965), Othello and Desdemona exchange a few words in Po’ Boy (2001), and Shakespeare himself appears in the alley in Stuck Inside of Mobile with the Memphis Blues Again (1966). Tears of Rage (1967) is based on King Lear and Seven Curses (1963) retells some of the story of Measure for Measure. For his part, Shakespeare was also a songwriter.’

The line between music and literature is blissfully straddled in both, and each soothes Man’s burdens with smooth assonance and alliterations. Creating beautiful plays of language.

Hampton-Reeves argues, ‘As You Like It is the most musical of Shakespeare’s plays, including the classics ‘Under the Greenwood Tree’ (later covered by Dylan’s contemporary Donovan) and ‘Blow, Blow, Winter Wind.’ Shakespeare also incorporated (and adapted) traditional ballads into his plays, many of which resemble Dylan’s early work.’ [88]

The long piece dedicated to Shakespeare in Dylan’s Nobel Prize speech can be heard against this fraternal backdrop. Perhaps the most comprehensive comparison of the two great artists so far has been written by Andrew Muir and is appropriately titled ‘The True Performing of It’. [89]

Dylan and Shakespeare share a great sense of humour and their works make many layered jokes about the tragicomedy of Man. We won’t do this now, but one could spend a lifetime delving into every line and appreciating the playful layered meanings of each.

Many Dylan fans do this often, me included, and Genius.com is a good place to begin. There, you will be met with some questionable speculation and some gold. But dedicated Dylanologists, who have followed his long journey and got to know our man and his work over many years, are your finest instructors for a deep dive. [90]

The Perennial Jester

Let us now look at Dylan’s infamous relationship with the press. This is one of the key avenues for him to harness the power of the jester to confuse and frustrate peddlers of nonsense, by flipping over their laughable questions and presumptions. [91] He still calls out their assumptions and misconceptions in interviews, even after all these years. Like Christ and Socrates, Bob Dylan favors sharp questioning to confound the ‘wise’ and avoids simplistic answers to life’s central concerns. [92]

The influence of surrealism was there in the early days, on display in a famous 1965 press conference in San Francisco. [93] It has served its purpose well, but this early trickster spirit has been replaced and reinforced since by more profound songs and playful responses as Bob has matured. This is glorious non-order used to restore precious order to a chaotic world fathered by lies.

As a Man, Dylan has refused to remain stagnant in the sixties or to be comforted by political ideologies forced down our throats as panacea for the world’s ills. This spiritual poet transcends the ‘disenchanted’ disorder of the age and will not rely on an ideological or mechanical fix any more than he did as a young man. He wants to be ‘re-enchanted’, but not have this enforced on him or others. [94]

From his troublesome time in the sixties, strung out on heroin and dedicated to the beat culture, to his motorcycle crash and Damascus-like conversion, Bob Dylan has been hungry for the bread of life. An older Dylan has shown how he overturned the famous Robert Johnson myth of the crossroads, by bargaining with ‘The Chief Commander’ instead of the devil. [95] This is the jester’s greatest trick and rewarded him with the spiritual food he was looking for:

‘Low cards are what I’ve got

But I’ll play this hand whether I like it or not

I’m sworn to uphold the laws of God

You could put me out in front of a firing squad

I’ve been out and around with the rowdy men

Just like you, my handsome friend

My head’s so hard, must be made of stone

I pay in blood, but not my own.’ (Pay in Blood) [96]

It has been a long and rising road since the iconic moments of the sixties which captured the nation’s attention, but he has ascended the mountain to earn the stars of literary genius by making and remaking great art.

The great jester figure performed another extraordinary flip, by overturning a resentful piece of poetry by Rimbaud into one of the most beautiful songs of human freedom in history. In Chimes of Freedom, he reverses Rimbaud’s poem of scorn for the poor and downtrodden and returns to Christ, the cosmic trickster. [97]

‘Even though a cloud’s white curtain in a far-off corner flared

And the hypnotic splattered mist was slowly lifting

Electric light still struck like arrows, fired but for the ones

Condemned to drift or else be kept from driftin’

Tolling for the searching ones, on their speechless, seeking trail

For the lonesome-hearted lovers with too personal a tale

And for each unharmful, gentle soul misplaced inside a jail

And we gazed upon the chimes of freedom flashing

Starry-eyed and laughing as I recall when we were caught

Trapped by no track of hours for they hanged suspended

As we listened one last time and we watched with one last look

Spellbound and swallowed ’til the tolling ended

Tolling for the aching whose wounds cannot be nursed

For the countless confused, accused, misused, strung-out ones and worse

And for every hung-up person in the whole wide universe

And we gazed upon the chimes of freedom flashin’. (Chimes of Freedom) [98]

Dylan grew to understand that, “There’s no black and white, left and right to me anymore; there’s only up and down and down is very close to the ground. And I’m trying to go up without thinking about anything trivial such as politics. They have got nothing to do with it. I’m thinking about the general people and when they get hurt.” [99]

He has never looked back, and his ‘re-enchantment’ belongs in a rigorously Judeo-Christian world. He is rooted in the ‘future tense’ [100] and most real of possible worlds, as Jordan reminded us with his quick dig into symbolism.

Enchantment can return for those of us happy to carefully consider the questions posed by our great world crises. David Brown walks with Dylan by suggesting we rediscover ‘place’ as more than just blind matter and space. He hopes God is understood to be ‘mediated through all of creation (human and divine) once again’. This is the return to the ‘symbolic world’ we spoke of before. Redeemed time and place reverses the world at the end of Bob’s scorn, that old world that has ‘no time to think.’ [101]

By following Dylan into ‘the divine realm’ [102] we revalue creation and the materials of human culture. To illustrate, Brown examines how this might occur with respect to place in all its various forms: nature, landscape painting, architecture, town planning, maps, pilgrimage, gardens, and sports venues. The ‘secular’ world is a myth and Dylan knows it. [103]

This re-enchantment of the world is everywhere in Dylan’s oeuvre, and has brought many of us home again. Dylan has brought us back to the symbolic world by invitation, in music and literature, via the myths of the Mediterranean and The Mississippi River. Riding on through the greats of the musical and literary ages, and by going back to The Bible. He is a rare storyteller, telling the ‘old, old story for modern times’. [104]

This is a man who claims that he ‘feels like he’s walking around in the ruins of Pompeii all the time.’ [105]

Michael Gilmour has shown, through precise images and events in Dylan’s life, such as a famous photo of Dylan next to Christ; how he has ‘sat at the foot of The Cross’ as both a ‘Roman soldier’ and as a ‘disciple’ like ‘the one whom God loved’. [106]

Displaying his knowledge of Bob as a deep symbolic artist. Dylan’s sensitivity to Christ and anti-Christ in one mind serves to remind us that we are fallen creatures mired in history but made for ‘transfiguration’. [107]

An interview with the classicist scholar, Richard Thomas, casts extraordinary light on Dylan’s lively experience with ‘transfiguration’ and his place in living history.

The interview beings, ‘Let’s go back to the classics. In “Why Bob Dylan Matters” you propose a new interpretation for Dylan’s concept of “transfiguration” that involves ancient Greek and Roman poets, and even a mysterious Rome library. Another word for transfiguration perhaps could be “intertextuality”. I believe that’s an essential part of your message and I’d be grateful if you could explain it.’

Thomas: ‘I’ll try. One of the many delights about being a classicist, working on the poetry of ancient Greece and Rome, and on the literature that flows down to us from back there, and now includes the songs of Bob Dylan, is that you connect song and poetry across the centuries.’

Richard Thomas inspires us here to partake in history with greater imaginative power,

‘You connect to what human genius produces at the highest artistic and aesthetic level in different languages and cultures.’ [108]

We must become cultural translators across time and space if we are to properly understand Man and real history. Our lack of cultural translation keeps us paddling in Kierkegaard’s shallow waters and the reeds of ideology. This has been shown in Logos Made Flesh, citing Wittgenstein. [109]

Echoing the great French artist Rene Girard, Classics Professor Thomas says,

‘All art is in imitation of and emulation with something that went before, what the Greeks call mimesis and zēlōsis, it puts itself in a tradition and competes with what comes before. That’s what T. S. Eliot meant when he wrote “immature poets imitate, mature poets steal.”

We saw this before in our brief comparison with Shakespeare and Dylan is still our Robin Hood, stealing from the riches of history to give to the poor in spirit:

‘That’s why Dylan started Tempest with a stolen line. We are supposed to recognize the theft — along with the melody — compare the two and see that Dylan’s song is both in a tradition and surpasses that tradition. A seven-verse folk song becomes a forty-five-verse epic.’

It is here we can begin to see Dylan’s growth and maturation from icon of the sixties and ‘voice of a generation’ to a deep voice for many generations. Professor Richard places what Dylan is doing first within an academic context, before adding an essential civilizational and spiritual one:

‘In my business this process is generally called intertextuality. What I write about is the way Dylan has in recent interviews, in the Nobel lecture, and elsewhere brilliantly remade this conscious compositional process into a mystical or spiritual one, “transfiguration.”

Thomas doesn’t doubt that, ‘There’s undoubtedly a hint at the transfiguration of Jesus in the Gospels of Matthew, Mark and Luke, when Jesus shone like the sun and his clothes became dazzlingly white with God’s power on the mountain, and Moses and Elijah turned up to talk to him.’

Then he ties several Dylan’s symbolic threads together for us,

‘I think that’s why Dylan tells Mikal Gilmore in the 2012 Rolling Stone that it was in “a library in Rome” that he read about transfiguration.

But Rome is also there because of the intertexts of pagans, Virgil and Ovid, who once lived in that city.’

The symbolic importance of this eternal city and our ancient foundations live in Dylan’s present and invite us into their timeless space through music and captivating stories. Thomas mentions Modern Times as an example:

‘In 2006, after the release of Modern Times with more than 20 lines of Ovid scattered across the songs, he tells Sean Lethem the songs “seemed to have an ancient presence” when he sang them — “in a reincarnative way, maybe.”

Here we see an American master return to the centre and history’s foundations, sojourning through the ruins of time. Now Professor Thomas reminds us that ‘This sort of mystical metaphor goes way back itself. Ennius, the father of Roman poetry, was the first to write Latin epic in the meter of Homer.

Ennius reports talking with Homer in a dream, and Homer tells him his soul has passed into Ennius, by way of a peacock, in accordance with Pythagorean principle of the transmigration of souls. You can’t make this shit up, as they say.’ [110]

Thomas is not alone, for those inclined to doubt. Grant Maxwell also locates Dylan’s references to books about ‘transfiguration’ within a fascinating layered history and appreciates the many levels of meaning Dylan is laying out:

‘The Transfiguration of Christ, which St. Thomas Aquinas referred to as “the greatest miracle,” is when Jesus shined radiantly upon a mountain (perhaps like the Beatles on the Cavern stage) and became mysteriously connected to the Hebrew prophets Elijah and Moses who appeared beside him.’

He goes on to say, ‘In the New Testament, Paul refers to the believers being “changed into the same image” through “beholding as in a glass the glory of the Lord,”[iv] which suggests that the witnessing of the transfigured individual can mediate a similar transformation in those who believe in that Transfiguration, acting as a mirror for the collective.’

Maxwell is astute enough to recognize something the Christian poet Dylan saw many years before, ‘Ultimately, the Transfiguration appears to have been fulfilled in the death and rebirth of Christ, which seems to be a kind of fractal reiteration of the archetypal death and rebirth of the shamanic initiation that Dylan appears to have experienced.’

Then we are shown a long lineage of those who have transfigured in some way, ‘As Dylan asserts, those few who are fundamentally transformed through this kind of process, by various accounts including primal shamans, ancient mythological heroes who traversed the underworld (Osiris, Dionysus, Heracles, Persephone, Orpheus, Psyche, Odysseus, Aeneas, Theseus, Gilgamesh, Odin, and others), figures from the Hebrew Bible (Jacob, Enoch, Elijah, Moses), the New Testament (Mary and Christ), and the Buddha, are reborn as new people, which separates them from the majority of humanity who have not undergone such a transformation.’

Maxwell quotes the transfigured Dylan himself to sharpen his point,

‘According to Dylan, this Transfiguration is not something that one can “dream up and think” in a hypothetical, conceptual way, but something that one either feels or does not.’

Maxwell finally distills the varieties of this religious experience into Dylan’s own:

‘From Dylan’s perspective, which is very much like that articulated by William James, one cannot choose one’s destiny. Rather, one either knows that one has been transfigured or one does not, and the skepticism of those who have not experienced Transfiguration, either in themselves or in others, has no bearing on the reality of the phenomenon. As it is expressed in several places in the New Testament, “He that hath ears to hear, let him hear.” [111]

T. Robert Wright brings our eyes to a book on Transfiguration by John Gatta which, ‘demonstrates in a masterful way how the Transfiguration, largely ignored by modernist theologians of a secularizing mindset, is in fact an organizing principle that bridges the immanence of this world with the transcendence of that which is to come . . .’ [112]

Dylan has long centred around this ‘organizing principle’, the person of God Himself, to live in the tension between ‘immanence’ and ‘transcendence’. This reiterates our earlier point that he should be seen as an ‘eschatological’ figure constantly focused on the end, or ultimate point, of creation. He sees God as the point and top of the mountain. [113]

To be candid, Dylan’s compositions are carved out of the high edifice of ageless art, arranged to bring us back into the elemental mysteries of life. This is reflected in the eternal city of Rome, which captures his imagination.

This city of profound symbolic power takes us back to the crucifixions of Sts Peter and Paul, and news seeds of Judeo-Christian place, no less than the ancient Roman empire and her poets of eternal life.

The eternal quality of Dylan mirrors the eternal nature of that holy city. This point is revealed to us clearly in the composition of Blowing’ in the Wind and its questions that will not go away:

‘How many roads must a man walk down

Before you call him a man?

How many seas must a white dove sail

Before she sleeps in the sand?

Yes, and how many times must the cannonballs fly

Before they’re forever banned?

The answer, my friend, is blowing in the wind

The answer is blowing in the wind

Yes, how many years can a mountain exist

Before it is washed to the sea?

Yes, and how many years can some people exist

Before they’re allowed to be free?

Yes, and how many times can a man turn his head

And pretend that he just doesn’t see?

The answer, my friend, is blowing in the wind

The answer is blowing in the wind

Yes, how many times must a man look up

Before he can see the sky?

Yes, and how many ears must one man have

Before he can hear people cry?

Yes, and how many deaths will it take till he knows

That too many people have died?

The answer, my friend, is blowing in the wind

The answer is blowing in the wind.’ (Blowin’ in the Wind) [114]

John 3:8 “The wind blows where it wishes and you hear the sound of it, but do not know where it comes from and where it is going; so is everyone who is born of the Spirit.” [115]

You Gotta Serve Somebody

At this point we might remember Dylan’s wrestles with those who peddle shameless falsehoods, selling untruths to be ‘relevant’. Those who desecrate words and their symbolic power.

The self-assured illusions of ‘priggery’, advertisers and false prophets are all guilty. Each of these, who twist the word have been exposed by Dylan. Dylan has replaced faith in them and their empire with a different kind of confidence, or trust, in God. [116]

Critics without ‘skin in the game’ [117] and those who ‘scapegoat’ [118] are condemned as being at odds with God and His non-orderly order.

Dylan has remembered God’s glorious Transfiguration at the top of the mountain and the dreadful ascent that saw The Christ’s skin pierced in agonizing crucifixion by those who turned against Truth. [119]

‘You may be an ambassador to England or France

You may like to gamble, you might like to dance

You may be the heavyweight champion of the world

You may be a socialite with a long string of pearls

[Chorus]

But you’re going to have to serve somebody, yes indeed

You’re going to have to serve somebody

Well, it may be the devil or it may be the Lord

But you’re going to have to serve somebody.’ (Gotta Serve Somebody) [120]

Transfiguration and Mature Man

‘Peace will come

With tranquillity and splendor on the wheels of fire

But will bring us no reward when her false idols fall

And cruel death surrenders with its pale ghost retreating

Between the King and the Queen of Swords.’ (Changing of the Guards) [121]

As we have seen, Bob Dylan has long been known as ‘the voice of a generation’, an icon of the sixties and America’s premier ‘protest singer’. Yet he has resisted unconstrained ideological ‘solutions’ that promise the sun, the moon and the stars forever, whilst playing a starring role in creating real justice. [122]

After the time spent out in the wilderness through the eighties and nineties, Dylan found his voice again. He found his ‘muse’ in the ruins of The Mediterranean, The Cross and the Music Canon. Murder Most Foul is the latest sign of this rediscovery.

He has returned to the heart of poetic and spiritual Man, releasing albums filled with mature ‘intertextual’ references to ancient poets, Christmas and continuing conversations with his musical guides.

We know from his songs, performances and rare interviews that he is still skeptical of utopian schemes and dreams, and still ‘a true believer’. [123]

Many of our own persistent problems come down to visions and dreams centered around Soveitchik’s ‘cognitive man’. This is the problem of ‘sin’ Dylan has dealt with. [124] Unlike Dylan, many of us never leave the lifeless desert wilderness we all face.

This is shown in the moral crisis we mentioned before and our inadequacy before the renewed specter of death. Politics can’t save us, as Bob Dylan has shown us repeatedly. Dylan is a rare prophet of responsibility and right.

According to Thomas Sowell, ‘It’s fashionable now to blame tribalism’ for the world’s major problems. He provides a different answer: ‘Individuals hold different visions, “constrained” or “unconstrained,” which entail different views of human nature, different senses of causation, in short, different ideas about the way the world works. It is the conflict between these macro visions that Sowell argues dominates history.’ [125]

Our present generation might revel in the ‘protest’ label, but to restrict Dylan to this fraction of character is to miss how much he has matured over the generations. In his arduous ascent, he has come to resemble Isaiah or Jeremiah as much as Virgil or Shakespeare.

If we ignore this, then we will miss what he can offer us in the twenty first century and long afterwards. [126]

The influence of Isaiah prints its indelible mark on Dylan’s American prophecy and was only germinating in his early career. We hear Isaiah’s existential lament echoed in All Along the Watchtower, later made famous by Jimi Hendrix.

“There must be some way out of here”

Said the joker to the thief

“There’s too much confusion

I can’t get no relief

Businessmen, they drink my wine

Plowmen dig my earth

None of them along the line

Know what any of it is worth.’ (All Along the Watchtower) [127]

Isaiah 21:5-9:

5: Prepare the table, watch in the watchtower, eat, drink: arise, ye princes, and anoint the shield.

6: For thus hath the Lord said unto me, Go, set a watchman, let him declare what he seeth.

7: And he saw a chariot with a couple of horsemen, a chariot of asses, and a chariot of camels; and he hearkened diligently with much heed:

8: And he cried, A lion: My lord, I stand continually upon the watchtower in the daytime, and I am set in my ward whole nights:

9: And, behold, here cometh a chariot of men, with a couple of horsemen. And he answered and said, Babylon is fallen, is fallen; and all the graven images of her gods he hath broken unto the ground.

Mastered by the Servant

Dylan has moved on from the early Gospel influences and inspiration of folks like Woody Guthrie to become ‘a property of Jesus’ through ‘a long obedience in the same direction’ with the prophets of Israel. [128]

The new disciple to Jesus, only ‘officially’ saved in the seventies has fulfilled the halakhic law of his youth and is demonstrably free from becoming the property of any mere ‘cognitive man’, or the works of their sinful hands.

Dylan’s experience of ‘being saved’ is more misunderstood than any other part of his life. The philosopher Dallas Willard can help us here by placing salvation next to discipleship in Christ:

“A disciple is a learner, a student, an apprentice – a practitioner… Disciples of Jesus are people who do not just profess certain views as their own but apply their growing understanding of life in the Kingdom of the Heavens to every aspect of their life on earth”

In a world of many ‘spiritualities’, both the sixties of Dylan’s chaotic youth and today, Willard shows what it means to be spiritual following Yeshua,“A person is a ‘spiritual person’ to the degree that his or her life is effectively integrated into and dominated by God’s Kingdom or rule”

It requires a work of cultural translation for the followers of secular faiths to begin to come to terms with the grammar of Christian life and inner laws, “The inner dimensions of life are what are referred to in the Great Commandment: ‘Love the Lord your God with all your heart, and with all your soul, and with all your strength, and with all your mind; and your neighbor as yourself’ (Luke 10:27).

Willard teaches carefully that, This commandment does not tell us what we must do so much as what we must cultivate in the care of our souls… a personality totally saturated with God’s kind of love, agape (see 1 Corinthians 13)” [129]

Dylan’s grown much since his youth in Hibbing, Minnesota, rambling through the songbook of American folk and canon of world music to create his unique sound. He has been formed as a disciple, writer and musician at the feet of good and living masters. His art is significant for America, her soul and Judeo-Christian civilization because it embodies spiritual power. Like Moses, he bears witness to the hard of heart and knows his song well that he is singin’. [130]

‘You can laugh at salvation, you can play Olympic games

You think that when you rest at last you’ll go back from where you came

But you’ve picked up quite a story and you’ve changed since the womb

What happened to the real you, you’ve been captured but by whom?’

He’s the property of Jesus

Resent him to the bone

You got something better

You’ve got a heart of stone.’ (Property of Jesus) [131]

Psychologist Robert L Moore once described the archetypal energies of Man by way of four images. Each of which can help us appreciate Dylan’s mature character: ‘warrior, magician, lover and king’.

America’s poet presents a model for these mature energies. The life blood from The Mississippi’s waters has met with the spirit of The Scriptures and heart of the great canon to create an iconic American Man for a nation of immigrants.

The mature Dylan casts a guiding light for those who fall short of the mature character of Man and is more important now than ever. America, in a time of increasing political idolatry, depression and substance abuse would do well to return to their central identities and what better guide than Dylan?

Moore reminds us that “In the absence of The King, the Warrior becomes a mercenary, the Magician becomes a sophist (able to argue any position and believing in none) and the Lover becomes an addict.’’

The US military-industrial complex, political sophistry and addiction to misplaced loves have all been condemned by Bob many times over as part of become the mature Man we see now and he has went through these shadow sands before coming out the other side.

According to Moore and Gillette, “The drug dealer, the ducking and diving political leader, the wife beater…all these men have something in common. They are all boys pretending to be men. They got that way honestly, because nobody showed them what a mature man is like.’’ [132]

Through listening to the ringing bells of real men like Dylan we might return to true living again. He imitates Christ to show what a true king, warrior, magician and lover looks like. We have his art as clear convicting testimony.

A Witness to the World

Now travelling around the world on the never-ending tour, Bob Dylan has played in front of millions from The USA to China, and memorably Japan.

In Communist China, he brought the crowd the wisdom of Isaiah and All Along the Watchtower. Whilst in Japan, he has boldly called any nonbelievers to join the transfiguration of the world backed by a magnificent orchestra, (All in front of a golden statue of The Buddha) [133]

‘Ring them bells, ye heathen

From the city that dreams

Ring them bells from the sanctuaries

’Cross the valleys and streams

For they’re deep and they’re wide

And the world’s on its side

And time is running backwards

And so is the bride

Ring them bells St. Peter

Where the four winds blow

Ring them bells with an iron hand

So the people will know

Oh it’s rush hour now

On the wheel and the plow

And the sun is going down

Upon the sacred cow

Ring them bells Sweet Martha

For the poor man’s son

Ring them bells so the world will know

That God is one

Oh the shepherd is asleep

Where the willows weep

And the mountains are filled

With lost sheep

Ring them bells for the blind and the deaf

Ring them bells for all of us who are left

Ring them bells for the chosen few

Who will judge the many when the game is through

Ring them bells, for the time that flies

For the child that cries

When innocence dies

Ring them bells St. Catherine

From the top of the room

Ring them from the fortress

For the lilies that bloom

Oh the lines are long

And the fighting is strong

And they’re breaking down the distance

Between right and wrong.’ (Ring Them Bells) [134]

Dylan’s mature moral leadership mirrors the magical measure of his musical restoration. Robert L Moore reminds us once again of Dylan’s ceaseless magical quality,

“The Magician archetype in a man is his “bullshit detector”; it sees through denial and exercises discernment. He sees evil for what and where it is when it masquerades as goodness, as it so often does.’

It is within this frame that we can see the complex canvas of Bob Dylan’s achievements. The tricky jester of the sixties bears witness to and becomes a new king in one:

‘In ancient times when a king became possessed by his angry feelings and wanted to punish a village that had refused to pay its taxes, the magician, with measured and reasoned thinking or with the stabbing blows of logic, would reawaken the king’s conscience and good sense by releasing him from his tempestuous mood. The court magician, in effect, was the king’s psychotherapist.” [135]

Murder Most Foul is the latest trick of the court magician to his ailing Republic but speaks clearly to any with ‘ears to hear’. [136]

Again, we are only on the surface of Dylan as a literary figure and we look forward to further revelations that should only add to his stature. In the third essay of this series we will look at how Dylan has matured in mind and soul over the years.

Notes

59- Nobel Prize (2017) Bob Dylan 2016 Nobel Lecture in Literature, Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6TlcPRlau2Q (Accessed: 2nd April 2020).

60-Lockerd, Benjamin (2010) The End of Literature, Available at: https://theimaginativeconservative.org/2010/07/end-of-literature.html (Accessed: 3rd April 2020).

61- Embry, Charles R. (2009) Eric Voegelin as Literary Critic, Available at: https://voegelinview.com/eric-voegelin-as-literary-critic-pt-1/ (Accessed: 2nd April 2020).

62- Ibid.

63- Ibid.

64-Heschel, Abraham Joshua (1997) Man Is Not Alone: A Philosophy of Religion , Reissue edition edn., USA: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

65- Ibid.

66- Dylan, Bob (2020) It’s Alright, Ma (I’m Only Bleeding), Available at: https://genius.com/Bob-dylan-its-alright-ma-im-only-bleeding-lyrics (Accessed: 3rd April 2020). Dylan, Bob (2020) My Back Pages, Available at: https://genius.com/Bob-dylan-my-back-pages-lyrics (Accessed: 3rd April 2020).

67-Wax, Trevin (2009) Counterfeit Gods: Tim Keller Takes On Our Idols , Available at: https://www.thegospelcoalition.org/blogs/trevin-wax/counterfeit-gods-tim-keller-takes-on-our-idols/ (Accessed: 2nd April 2020).

68-Dylan, Bob (2020) Series of Dreams, Available at: https://genius.com/Bob-dylan-series-of-dreams-lyrics (Accessed: 3rd April 2020).

69- Ibid.

70- Dylan, Bob (2020) I Shall Be Released, Available at: http://www.bobdylan.com/songs/i-shall-be-released/ (Accessed: 3rd April 2020).

71-Ibid.

72-Wax, Trevin (2013) Why the Form of Worship Matters: A Conversation with James K. A. Smith , Available at: https://www.thegospelcoalition.org/blogs/trevin-wax/why-the-form-of-worship-matters-a-conversation-with-james-k-a-smith/ (Accessed: 2nd April 2020).

73-Dylan, Bob (2020) It Ain’t Me, Babe, Available at: https://www.bobdylan.com/songs/it-aint-me-babe/ (Accessed: 4th April 2020).

74- Pearce, Joseph (2018) Who’s on the Right Side of History?, Available at: https://theimaginativeconservative.org/2018/06/whos-right-side-history-joseph-pearce.html (Accessed: 2nd April 2020).

75-Dylan, Bob (2020) Bob Dylan’s Dream, Available at: https://www.bobdylan.com/songs/bob-dylans-dream/ (Accessed: 3rd April 2020).

76-Solzhenitsyn, Aleksandr (2003) The Gulag Archipelago, 01 edition edn., USA: Harvill Press.

77- Dylan, Bob (2020) With God on Our Side, Available at: http://www.bobdylan.com/songs/god-our-side/ (Accessed: 3rd April 2020).

78-Wilentz, Sean (2011) Bob Dylan In America, USA: Vintage.

79- McLean, Don (2020) American Pie, Available at: https://genius.com/Don-mclean-american-pie-lyrics (Accessed: 3rd April 2020).

80- Polyphonic (2018) American Pie Explained: Don McLean’s Cultural History of Rock n’ Roll, Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bLEUlvRi8m8 (Accessed: 2nd April 2020).

81-Polyphonic (2018) American Pie Explained: Don McLean’s Cultural History of Rock n’ Roll, Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bLEUlvRi8m8 (Accessed: 2nd April 2020).

82-Dylan, Bob (2004) Blood On The Tracks Remastered , Available at: https://www.amazon.co.uk/Blood-Tracks-Bob-Dylan/dp/B0001M0KE8 (Accessed: 4th April 2020).

83- Storytellers (2016) The Big Lebowski: A Carnival of Society, Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kpPTQb08ZfM (Accessed: 2nd April 2020).

84-Markhorst, Jochen (2018) Jokerman by Bob Dylan. The one that got away., Available at: https://bob-dylan.org.uk/archives/9193 (Accessed: 2nd April 2020).

85- Ellul, Jacques (2014) Betrayal of the West, Available at: https://archive.org/details/BetrayalOfTheWest/mode/2up (Accessed: 2nd April 2020).

86-Ramachandra, Vinoth (2005) The Scandal of Jesus: Christ in a Pluralist World , Available at: http://www.mhs.no/uploads/reichelt_lecture_2005.pdf (Accessed: 4th April 2020).

87- Thomas, Richard F. (2017) Why Dylan Matters, USA: William Collins.

88-Hampton-Reeves, Stuart (2016) Dylan and Shakespeare, Available at: http://bloggingshakespeare.com/dylan-and-shakespeare (Accessed: 4th April 2020).

89- Muir, Andrew (2019) Bob Dylan & William Shakespeare: The True Performing of It, USA: Red Planet.

90-Faena Aleph (2020) A brief introduction to Dylanology, Available at: https://www.faena.com/aleph/articles/a-brief-introduction-to-dylanology/ (Accessed: 3rd April 2020).

91-Polyphonic (2019) Bob Dylan vs. The Press, Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ljkfcgXxzX8 (Accessed: 4th April 2020).

92- Kreeft, Peter (1987) Socrates Meets Jesus, USA: Intervarsity Press.

93-Polyphonic (2019) Bob Dylan vs. The Press, Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ljkfcgXxzX8 (Accessed: 4th April 2020).

94-Ehrett, John (2017) Technology and the Re-Enchanted World, Available at: https://ethikapolitika.org/2017/05/18/technology-re-enchanted-world/ (Accessed: 2nd April 2020).

95-All Dylan – A Bob Dylan blog (2016) November 19: The classic Bob Dylan “60 Minutes” interview with Ed Bradley – 2004, Available at: https://alldylan.com/bob-dylan-the-classic-60-minutes-interview-with-ed-bradley-19-november-2004-video/ (Accessed: 4th April 2020).

96-Dylan, Bob (2020) Pay in Blood, Available at: https://genius.com/Bob-dylan-pay-in-blood-lyrics (Accessed: 4th April 2020).

97-Schall, Fr. James V. (2018) What is Easter? Available at: https://www.crisismagazine.com/2018/what-is-easter (Accessed: 4th April 2020).

98- Dylan, Bob (2020) Chimes of Freedom, Available at: https://www.bobdylan.com/songs/chimes-freedom/ (Accessed: 3rd April 2020).

99-Ibid

100-Sacks, Rabbi Jonathan (2011) Future Tense: A vision for Jews and Judaism in the global culture, UK: Hodder & Stoughton.

101- Ibid.

102-Lampert, Evgueny (1944) THE DIVINE REALM: TOWARDS A THEOLOGY OF THE SACRAMENTS, 1st edn edition edn., USA: Faber & Faber.

103-Cayley, David (2015) The Myth of the Secular, Available at: http://www.davidcayley.com/podcasts/2015/3/21/the-myth-of-the-secular (Accessed: 4th April 2020).

104- Gilmour, Michael J (2011) The Gospel According to Bob Dylan: The Old, Old Story of Modern Times , USA: Westminster John Knox Press.

105-Gilmore, Mikal (2001) Bob Dylan, at 60, Unearths New Revelations, Available at: https://www.rollingstone.com/music/music-news/bob-dylan-at-60-unearths-new-revelations-86631/ (Accessed: 4th April 2020).

106- Ibid. See also: Gilmour, Michael J. (2004) Tangled Up in the Bible: Bob Dylan and Scripture, USA: Continuum

107- Ibid.

108-Zoppas, Marco (2019) Why Bob Dylan Matters: An Interview with Richard F. Thomas, Available at: https://medium.com/mitologie-a-confronto/why-bob-dylan-matters-514e659980b0 (Accessed: 2nd April 2020).

109-Miller, Matt (2020) Logos Made Flesh, Available at: https://www.youtube.com/user/youthnation1 (Accessed: 4th April 2020).

110- Ibid.

111- Maxwell, Grant (2014) How Does It Feel? Elvis Presley, The Beatles, Bob Dylan, and the Philosophy of Rock and Roll , USA: Persistent Press.

112- Gatta, John (2016) The Transfiguration of Christ and Creation, USA: Wipf & Stock.

113-Diocese of Little Rock (2014) God speaks to us on tops of mountains, Available at: https://www.dolr.org/article/god-speaks-us-tops-mountains (Accessed: 4th April 2020).

114- Ibid.

115- Ibid.

116-CSLewisDoodle (2016) After Priggery – What? (On Wicked Journalists) by C.S. Lewis Doodle, Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IE4oZ6F-gQM (Accessed: 2nd April 2020).

117- Taleb, Nassim Nicholas (2018) What do I mean by Skin in the Game? My Own Version, Available at: https://medium.com/incerto/what-do-i-mean-by-skin-in-the-game-my-own-version-cc858dc73260 (Accessed: 2nd April 2020).

118- Girard, René (2015) The Scapegoat: René Girard’s Anthropology of Violence and Religion, Available at: http://www.davidcayley.com/podcasts/2015/3/8/the-scapegoat-ren-girards-anthropology-of-violence-and-religion-2 (Accessed: 4th April 2020).

119- Rutledge, Fleming (2015) The Crucifixion: Understanding the Death of Jesus Christ, Reprint edition edn., USA: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co.

120- Dylan, Bob (2020) Gotta Serve Somebody, Available at: https://genius.com/Bob-dylan-gotta-serve-somebody-lyrics (Accessed: 3rd April 2020).

121- Dylan, Bob (2020) Changing of the Guards, Available at: http://www.bobdylan.com/songs/changing-guards/ (Accessed: 3rd April 2020).

122- Sowell, Thomas (2007) A Conflict of Visions: Ideological Origins of Political Struggles , USA: Basic Books.

123-White, Rev. Brent L. (2009) Dylan: “Well, I am a true believer.”, Available at: https://revbrentwhite.com/2009/11/27/dylan-well-i-am-a-true-believer/ (Accessed: 4th April 2020).

124-Ricks, Christopher (2016) Dylan’s Visions of Sin, UK: Amazon Media EU S.à r.l. .

125- Ibid.

126-Ibid.

127- Dylan, Bob (2020) All Along the Watchtower, Available at: https://genius.com/Bob-dylan-all-along-the-watchtower-lyrics (Accessed: 3rd April 2020).

128- Peterson, Eugene H. (2019) A Long Obedience in the Same Direction: Discipleship in an Instant Society, Commemorative edition edn., USA: IVP Books.

129-Willard, Dallas (2009) The Great Omission: Reclaiming Jesus’s Essential Teachings on Discipleship, Reprint edition edn., USA: HarperOne.

130-Beckwith, Francis (2017) This Is Why Bob Dylan’s Genius Is Biblical, Available at: https://www.ncregister.com/blog/guest-blogger/this-is-why-bob-dylans-genius-is-biblical (Accessed: 3rd April 2020).

131- Ibid.

132- Moore, Robert L. (1992) King Warrior Magician Lover: Rediscovering the Archetypes of the Mature Masculine, New edition edn., USA: Bravo Ltd.

133-NanchatteDesu (2014) Ring Them Bells – Bob Dylan Live Concert in Japan (HD), Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=l-0tiTiUdv0 (Accessed: 4th April 2020).

134-Dylan, Bob (2020) Ring Them Bells, Available at: http://www.bobdylan.com/songs/ring-them-bells/ (Accessed: 3rd April 2020).

135- Ibid.

136-Bible Project (2020) How to Read the Parables of Jesus Are the Parables of Jesus Confusing on Purpose?, Available at: https://bibleproject.com/blog/are-the-parables-of-jesus-confusing-on-purpose/ (Accessed: 4th April 2020).

This is the second of three parts with parts one and three available.