Bob Dylan: Murder Most Foul and America’s Soul (Part I)

Hope Amidst Crisis

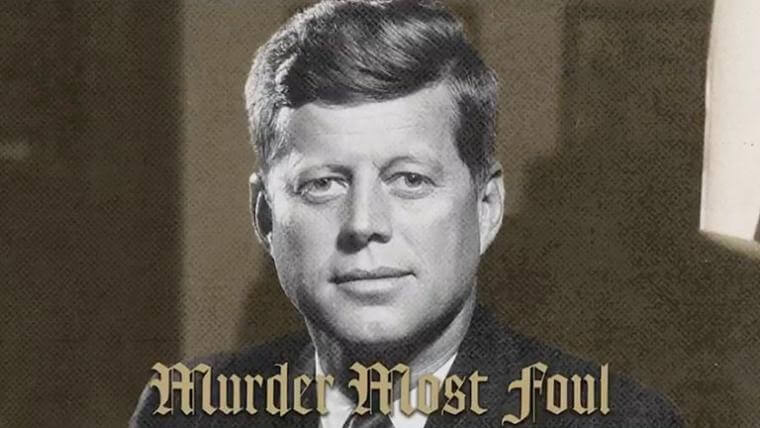

Bob Dylan has only gone and released a new song, his first original music in eight years, right in the heart of the crisis of Covid-19. This came as a seventeen-minute ballad named Murder Most Foul and is ostensibly about the death of JFK. [1]

The song was already heard on YouTube a few million times within a week and asks some important questions. Dylan, who makes a habit out of asking probing questions at the right time, asks who are we? Especially in times of great emergency.

With Covid-19 and the crises of 2020, we are now in the hard clutch of another great crisis, but we’ve been here before. Dylan reminds us that the road of history has been long and weary.

How timely then that America’s greatest living poet and musician Bob Dylan has, at the stroke of dark midnight, cast our minds back to another time of desolation in living history. With Murder Most Foul, he has reminded us of the dark day in Dallas in 1963, when Kennedy died. All of that and much more besides.

Whilst many of us have been waiting for the return of music’s stately king since his last new music release many years ago, many more were taken by surprise. However, the timing could not be better and Murder Most Foul has arrived by the hand of soothing providence.

With this seventeen-minute ballad – its title drawn from the great tragic bard of western civilization, William Shakespeare- Bob Dylan has gone full circle to the inspired days of his youth. Back to when he was known as ‘the voice of a generation’, and back to the deep roots of living civilization. [2]

America’s troubadour is looking back around after a long trek up the mountain, to his own foundational early songs of prophecy such as With God on Our side and Pawn in the Game, and towards the great American songbook to which he belongs.

This haunting ballad may even be the ‘symphony’ that Dylan said he wanted to compose way back in 1965, at a famous press conference in San Francisco.

Dylan has walked a long walk through the decades since then. From the iconic early moments of the sixties, such as Newport Folk Festival and surrounding utopian promise of Woodstock, to New York City and Café Wha; Dylan has moved on through despair, divorce and disillusionment before rising again to ‘…reflect it from the mountain so all souls can see it’. [3]

He’s travelled the world many times over, through life’s valleys and troughs in love and loss, but never lost hope in the midst of history. Murder Most Foul reiterates once again Dylan’s unceasing message of hope against the mess of death and decay. America’s troubadour is speaking to America’s soul once more.

‘But his soul was not there where it was supposed to be at

For the last fifty years they’ve been searchin’ for that

Freedom, oh freedom, freedom over me

I hate to tell you, mister, but only dead men are free

Send me some lovin’, then tell me no lie

Throw the gun in the gutter and walk on by

Wake up, little Susie, let’s go for a drive

Cross the Trinity River, let’s keep hope alive.’ (Murder Most Foul) [4]

The day has come for us to return home again. Even if Covid-19 has forced our hand. Yet, the timing of this release at the hour of the world’s dark midnight speaks to the providential light which has guided Dylan’s work all along.

America Today

Now, in the age of ‘the Anti-Christ’, which had ‘only begun’ with Kennedy’s assassination and ‘the Aquarian age’, Dylan is calling us back to our Holy centre. Back to America’s great songbook, back to The Bible, ‘the port of King James’ and back to the enduring icons of literature: to Ovid and Homer and Shakespeare too. The song’s title is just the first clue. [5]

For any new fans or investigators amongst the millions who have now listened to Murder Most Foul on YouTube and been moved to read this essay, Bob Dylan is a complex songwriter who layers his songs with several meanings. Filling almost every sentence with allusions to events in history, music, literature and The Holy Bible.

With Murder Most Foul, ‘His Bobness’ beckons us to return once more to the giant sequoias of music, Beethoven’s Sonata, Gospel, ‘all that jazz’ and the southern Blues. [6]

Again, to receive the great books which speak what it means to live truly and become once more good citizens and children of God. Bob calls for a return to the beauty and drama of history, especially the history he knows best: the storied history of American music. From the North Country, Deep South, East Coast and The Old West.

Dylan’s calling the roll after a long and full musical life so far: Full of madness and loss, love and marriage, divorced despair and salvation, sin and death. He ‘knows the songs well’ and he’s still singing. [7]

‘I’m Goin’ to Woodstock, it’s the Aquarian Age

Then I’ll go to Altamont and sit near the stage

Put your head out the window, let the good times roll

There’s a party going on behind the Grassy Knoll…

They killed him once and they killed him twice

Killed him like a human sacrifice

The day that they killed him, someone said to me, “Son

The age of the Antichrist has just only begun” (Murder Most Foul) [8]

Dylan’s unexpected return calls us again to ask the eternal questions. The same kinds of questions that he was asking way back in the shadow of Kennedy’s death and dark specter of Nuclear War. There was a cold freeze then over nations and the north country where he grew up.

‘How many years must one man have, before he can hear people cry?

How many deaths will it take till he knows too many people have died?

The answer, my friend, is blowing in the wind.’ (Blowing in the Wind) [9]

For too long, our own present age has ignored the problems of death recalled by Murder Most Foul and the foul crises of 2020. The call to deep questions has been hushed for some time now. And it seems that Dylan has long cried out in the wilderness. But now that death is at the door, we might just pay attention once more.

We creatures of the internet age and the hyperreal tend to fluctuate between uninspired lives hiding death and morbid fascination with its seemingly unending power. But we inherit a dark tradition that goes back some time.

Soren Kierkegaard described the problem of ‘The Present Age’ as far back as the nineteenth century:

‘The present age is one of understanding, of reflection, devoid of passion, an age which flies into enthusiasm for a moment only to decline back into indolence. Not even a suicide does away with himself out of desperation, he considers the act so long and so deliberately, that he kills himself with thinking — one could barely call it suicide since it is thinking which takes his life.’

Kierkegaard continues,

‘He does not kill himself with deliberation but rather kills himself because of deliberation. Therefore, one cannot really prosecute this generation, for its art, its understanding, its virtuosity and good sense lies in reaching a judgment or a decision, not in taking action.

Just as one might say about Revolutionary Ages that they run out of control, one can say about the Present Age that it doesn’t run at all’. Action and passion is as absent in the present age as peril is absent from swimming in shallow waters…’ [10]

The indolent cloud of mediocrity that has hung over many of us may be about to let out its rain. The silver lining of our current worldwide crisis might prompt us to act. We have a chance now to respond to our enforced cultural climate change by entering deeper waters. We might hope with Dylan, who released Murder Most Foul in full mind of our struggle, that there be renewed attention to death and new life. The storm of 2020 may be the dreadful ‘whirlwind’ that blows away our complacency to make us anew. Like Job we might find some answers here. [11]

According to Alexander Schmemann, “…In order to console himself, man created a dream of another world where there is no death, and for that dream he forfeited this world, gave it thus decidedly to death.’

But Dylan has posted Murder Most Foul as a letter to America that she might live.

Schmemann goes on, ‘Therefore, the most important and most profound question of the Christian faith must be, how and from where did death arise, and why has it become stronger than life?’ [12]

Murder Most foul ponders the same key question and wrestles with death.

‘We’re gonna kill you with hatred, without any respect

We’ll mock you and shock you and we’ll put it in your face

We’ve already got someone here to take your place

The day they blew out the brains of the king

Thousands were watching, no one saw a thing.’ (Murder Most Foul) [13]

Schmemann wonders, ‘Why has death become so powerful that the world itself has become a kind of global cemetery, a place where a collection of people condemned to death live either in fear or terror, or, in their efforts to forget about death, find themselves rushing around one great big burial plot?” (O Death Where is Thy Sting?) [14]

Now, let’s look at life. In particular the life of our subject Bob Dylan. A young Jewish boy from Minnesota, born as close in time to the holocaust as he was in place to The Mississippi River. Dylan knew from early on, and knows better now, how powerful the current of life’s great suffering can be. However, as a descendent of Jewish immigrants from Odessa, in modern Ukraine and The Bible’s Job, he was brought up to know that suffering can form us into a deeper life. And what Rabbi Soloveitchik called ‘Halakhic Man’. We shall return to him shortly. [15]

First, we will continue to paint a brief sketch of our great artist, Bob Dylan. The songwriter, and performer, was originally named Robert Allen Zimmerman. The son of Abraham and Beatty Zimmerman, he was born in Duluth, Minnesota and spent much of his childhood in nearby Hibbing.

This was a pretty typical poor mining town with a small Jewish population. Young Robert celebrated his bar mitzvah in Harding but did not obviously identify with his Jewish identity.

From early on, he presented himself under the name Bob Dylan, adopting a persona as a typical mid-Western American. But under the surface the well of Jewish influence was far from dry and would provide plentiful water for the singer to draw on throughout his career.

It is easy to find Judeo-Christian influences in Bob’s catalogue not far in time from when Kennedy died in Dallas. The opening verse of “Highway Sixty-One Revisited” as early as 1965 retells the story of the binding of Isaac. God is telling Abraham to “Kill me a son!” Abe replies, “Man, You must be putting me on.” [16]

His comical relationship with God–the imagined argument with the Almighty–is a staple of Jewish culture found in Orthodox texts and Judaism in popular culture alike. (Fiddler on the Roof is one example.) Abraham is treated as family in the song: He is ‘Abe,’ just as Dylan’s father was named Abe.

Dylan has been concerned with life’s big questions forever and has waded into the deep waters of The Bible time and again. The songs on the later John Wesley Harding album, such as “I Dreamed I Saw St Augustine,” contain clear references to The Scripture. On this 1967 album, Dylan is conjuring up images from and commemorating the American Old West with a brush in each hand. [17]

Some colorful lifelong Dylan motifs made their way into view on this album. John Wesley Harding was a noble outlaw for one, with qualities reminiscent of medieval Robin Hood, taking from the rich to give to the poor. The young Zimmerman was sketching early outlines, drawn from the past, that would return in his later work.

Murder Most Foul’s appearance amidst the hard times of Covid-19 repeats a pattern for Dylan, who has ridden into the storm of chaos many times before. One famous example can be drawn from the mid seventies when Bob went on a whirlwind tour, documented masterfully in Scorsese’s Rolling Thunder Revue. [18]

At the time, America was continuing a decadent descent into chaos began in the ‘aquarian age’ of the sixties. By then, Dylan had been cast aside by some former fans as no less than ‘Judas’, and was going through a painful separation with his wife Sara. [19]

An immature Dylan responded to the chaos with his own disorder. Descending further into despair. The carnival atmosphere of the tour, made clear by Scorsese’s documentary, featured excessive masks, hysterics and performances of irreverent revelry. This circus disorder combined to ramp up the chaotic ardor in Dylan’s life and serves as an insight into the seventies more broadly. This is one way a jester deals with chaos. But later, Dylan would learn that there is another higher way and he was always more than just a jester anyway.

Back to Halakhic Man

The works of the one of the twentieth century’s most remarkable spiritual figures, Rabbi Soloveitchik’s writings shine a light on the Jewish seeds of Dylan’s early spiritual genius. Especially his premier books: Halakhic Man (1944) and Lonely Man of Faith (1965). The man known as ‘The Rav’ paints a picture of the inner life of the religious Jew by comparing and contrasting between various religious and philosophical “types.”

‘In Halakhic Man, Soloveitchik analyzes the ideal religious Jew (“Halakhic Man”) in comparison with two other human types: Cognitive Man and Homo Religiosus–Religious Man.’

The Rav suggests that, ‘Cognitive Man’s approach to life is that of a scientist, in particular a theoretical physicist or mathematician, exploring reality by constructing ideal intellectual models and analyzing the imperfect, concrete world in their terms.’

Arguing that, ‘Homo Religiosus, on the other hand, seeks what Abraham Joshua Heschel termed “radical amazement,” the capacity for spiritual experience, transcending physical reality by experiencing God’s presence in the world.’

He then draws a distinction between ‘religion’ and his Judaism, ‘One might assume that the ideal religious Jew is similar to Homo Religiosus, but Soloveitchik relates him (or her) to Cognitive Man: Just as Cognitive Man approaches reality armed with a pre-prepared intellectual model, so too Halachic Man comes to the world armed with the Torah, revealed by God at Mount Sinai.’

The context creates a hierarchy:

‘If scientists initially understand reality in mathematical terms, Halachic Man understands it in Jewish legal categories. For Halachic Man, seeing the first light of dawn breaking over the horizon is not primarily an aesthetic experience. Rather, his first thought is, “it’s time to recite the Shema.’

With this in mind, ‘For Soloveitchik, Halachic Man intuitively experiences the world in Jewish categories, as if he were wearing a pair of “halakha-tinted” glasses. As such, observing the mitzvot (plural of mitzvah ) is no effort for him–an observant lifestyle is a natural outcome of his basic orientation to reality.’ [20]

It is within this milieu that we can see young Dylan more clearly. However, the law as understood by both Soloveitchik and Heschel is a stepping-stone to freedom. ‘The law’ forms Man as a moral and intellectual creature to see the world as it really is and frees him from the pretentious illusions of one-dimensional thinking. It is the height of Piaget’s playful ‘iterated game’, whereby Man asks what the best thing is in the long term, for oneself and others. [21]

Moreover, with the profound Christian influences pressing upon Bob from friends, his experiences with ‘Yeshua’ and the spiritual fire he found in the old songs; this Halakhic chapter was never going to be the whole of the story. [22] Those categories of Man were made to be ‘transfigured’ as he matured on his long sojourn. [23]

From near the beginning, Bob has been captivated by the end of time and what is referred to as ‘eschatology’. The Boy who grew up surrounded by the uncertainty of The Cold War knew from The Bible that ‘a hard rain’s a-gonna fall’ and felt an urgency to answer the essential call to honest living that his unripen halakhic instincts rang.

He wrestled with drugs and the desire to end his own life at the height of his sixties fame, revealing the hard details of a suicide wish to Robert Shelton in an early interview. [24] But he was not destined to fall into the ‘27 club’ that took many of his musical fellows. [25]

Coming of Age and The Ages

Dylan takes history seriously even when he doesn’t take it ‘literally’. In a culture where shared cultural and philosophical assumptions have conditioned our understanding of history in ways that make the idea of divine action in history problematic, Dylan is a breath of fresh air. The one-dimensional nature of secular history is too simplistic for Dylan and he rebels against the idols of time.

‘Socialism, hypnotism, patriotism, materialism

Fools making laws for the breaking of jaws

And the sound of the keys as they clink

But there’s no time to think.’ (No Time to Think) [26]

This is a remarkable quality shared with the world’s leading Biblical scholar, NT Wright, who argues that historical study can win from ancient Jewish and Christian cosmology and eschatology a renewed way of understanding the relationship between God and the world. He has even covered Bob’s song, When the Ship Comes In, [27] which is a number saturated in musings about the end of the world and God’s work to redeem the cosmos:

‘Oh, the time will come up

When the winds will stop

And the breeze will cease to be breathin’

Like the stillness in the wind

Before the hurricane begins

The hour that the ship comes in

And the sea will split

And the ships will hit

And the sands on the shoreline will be shaking

Then the tide will sound

And the waves will pound

And the mornin’ will be a-breakin’

(When the Ship Comes In) [28]

N. T. Wright mirrors our musical prophet by destroying socially constructed myths about the separation between ‘secular’ and ‘sacred’, ‘natural’ and ‘supernatural’. [29] They re-enchant the world by re-entering real time. By focusing on the end -or the point- of creation, Dylan and Wright see anew past, present and future.

This is a more ancient ‘shabbat’ mindset that provides ‘shalom’. Dylan would have known this from a young age and returned to this alongside his return to ancient Greek poetry and the many deep influences steering his music and lyrics.

By experiencing creation by the light of God’s time they are given peace. America may have won the Cold War but it came at the cost of destroying her older fabric. YouTube channel Logos Made Flesh shows this fall into slavery by mechanical time by comparing older views, symbolized by eternity, with newer time and its technologies. We rush constantly now to serve the idols of the age, whether that be the market, state or some other god that demands our time as a sacrifice. [30] Dylan describes this in No Time to Think:

‘Bullets can harm you and death can disarm you

But no, you will not be deceived

Stripped of all virtue as you crawl through the dirt

You can give but you cannot receive

No time to choose when the truth must die

No time to lose or say goodbye

No time to prepare for the victim that’s there

No time to suffer or blink

And no time to think.’ (No Time to Think)

The historian Wright joins Dylan in taking a different road- back from the illusions of ‘progress’. [31] Going back so that they may go forward again in the right direction and at the right pace.

‘We all want progress, but if you’re on the wrong road, progress means doing an about-turn and walking back to the right road; in that case, the man who turns back soonest is the most progressive.’ – C.S Lewis [32]

Wright develops a distinctive approach to ‘natural theology’ grounded in what he calls an ‘epistemology of love’. This approach, which sees the universe as good and receiving redemption along with Man, arises from his reflection on the significance of the ancient Judeo-Christian concept of the ‘new creation’. [33] This is revolutionary for our understanding of the reality of the world, the reality of God and their intimate links to one another. Dylan accomplishes the same feat through his art and started in the sixties with stark prophetic warnings about the destruction of Man and the world.

‘And what’ll you do now, my blue-eyed son?

And what’ll you do now, my darling young one?

I’m a-goin’ back out ‘fore the rain starts a-fallin’

I’ll walk to the depths of the deepest dark forest

Where the people are many and their hands are all empty

Where the pellets of poison are flooding their waters

Where the home in the valley meets the damp dirty prison

And the executioner’s face is always well hidden

Where hunger is ugly, where souls are forgotten

Where black is the color, where none is the number

And I’ll tell and speak it and think it and breathe it

And reflect from the mountain so all souls can see it

And I’ll stand on the ocean until I start sinkin’

But I’ll know my song well before I start singin’

And it’s a hard, it’s a hard, it’s a hard, and it’s a hard

It’s a hard rain’s a-gonna fall.’ (A Hard Rain is Gonna Fall) [34]

Let’s know our song well before we start singin’.

Disorder and Desolation

‘Loneliness, tenderness, high society, notoriety

You fight for the throne and you travel alone

Unknown as you slowly sink

And there’s no time to think.’ (No Time to Think) [35]

Murder Most Foul has fallen at a time of continued moral chaos and might help us restore a comforting moral center. Dylan, besides serving us as a musical and literary icon, has acted as an authoritative moral leader for America and all Man.

All without succumbing to The Messiah Complex of many a celebrity. The more he refuses to offer oversimple moralist solutions, the higher his moral stature becomes. He has made some of the best ‘moral’ music of the last fifty years. Murder Most Foul follows this trend.

Dylan fan and former Chief Rabbi of Britain, Jonathan Sacks, has recently written an excellent book on Morality to combat the confusions of our culture about what it means to live rightly.

Echoing Dylan, he proclaims that we are living through a period of ‘cultural climate change’ that reflects the earth’s own. A discerning philosopher by training, he calls our attention to the central problems we face together.

Our communities, he says, have fallen apart as we have ‘outsourced morality to the markets on the one hand, and the state on the other. The markets have brought wealth to many, and the state has done much to contain the worst excesses of inequality’, but neither can bear the moral weight of showing us how to live a good and rich life.

This idolatry of market and state has had a profound impact on society and the way we interact with each other. Traditional Judeo-Christian values no longer hold, and recent political swings show that modern gods of tolerance and equality have left many feeling rudderless and adrift. Ill prepared for ‘when the ship comes in.’

In this environment we see things fall apart in shocking ways – poisonous public discourse makes genuine social progress almost impossible, and a more divisive society, without a common language or reverence for the word, is fueled by the consuming fires of identity politics and extremism.

The rise of the cult of victimhood calls for ‘safe spaces’ but stops honest debate. The inordinate influence of social media seems all-pervading and the fragmenting of the family is just one result of the loss of ‘social capital’.

Within this climate, many feared what the future might hold even before Covid-19 and the curses of 2020.

Sacks echoes Dylan by calling us back to more ancient ways that have stood the test of time. We are called to revere the word with careful and truthful speech, and to act with love by putting ‘We’ and ‘I’ in their rightful place.

Sacks’s book joins Dylan’s music by offering a devastating critique of our modern condition, uprooting many of its causes and idols. From the ancient Greeks through the Reformation and Enlightenment right up to the present day.

Rabbi Sacks argues that there is ‘no liberty without morality and no freedom without responsibility’. [36]

This is a message Dylan has been preaching and living for a half a century now, from his early ‘halakhic’ upbringing to later life in Christ. Bob offers us a model of how we should live in truth by approaching history, language, music, literature and our great religions with humble seriousness.

Many times, he has spoken out against injustice, taking on the cause of individuals and got to know them well. Most notably, Hurricane Carter upon who the song ‘Hurricane’ is based. [37] This respect for persons and character is present in his art and moral life in equal measure.

With the wisdom of Ecclesiastes, he has also held his tongue when it has been a time for silence and resisted the restricting labels of ‘protest singer’, or ‘voice of a generation’. [38]

Why? So, he could ‘reflect it from the mountain so all souls can see it’ and speak for many generations. [39]

Unlike the ideologue, Bob knows in his bones that we live in a ‘symbolic world’ of meaning and moral purpose. R [40]

The follies of modern philosophers and sophists have failed to sway him from his foundations:

‘May you have a strong foundation; When the winds of changes shift.’ (Forever Young) [41]

Back in the moral revolution of the sixties, Dylan made his way from small town Minnesota to the city of New York. He was on a journey to meet folk singer Woody Guthrie as he lay sick in hospital. This was a formative time in young Bob’s life and the person of Woody embodied the well of American folk tradition that he’d grown to love.

The elder statesman of folk even helped impress upon the young Jewish man’s soul the central role of Jesus Christ in history. Moving him by stories, music and by faith, and revealing the world of American symbols. At this point we might look to the lyrics of Guthrie’s song Jesus Christ, which he and Dylan would perform together in the sixties. This song and the meaning behind it were to have lasting effects on Dylan until this day:

‘Jesus Christ was a man who traveled through the land

A hard-working man and brave

He said to the rich, “Give your money to the poor,”

This song was written in New York City

… Of rich man, preacher, and slave

If Jesus was to preach what He preached in Galilee,

They would lay poor Jesus in His grave.’ (Jesus Christ) [42]

A Poet of the Symbolic World

A fellow traveler in the world of symbols, James B Jordan, helps us get inside the layered world Dylan inhabits. By describing Judeo-Christian symbolism and decrying the simplistic make-believe and upside-down world of modern ideology.

Jordan warns that our present collective deception is even worse than the sophistry of the ancients. This modern ‘secular’ faith causes the chariots of civilizations to crash harder than the chaotic cyclical eras of antiquity. We will see later that the new moral disorder smashes the structure of great music too.

Jordan begins, ‘Modern philosophy, especially after Immanuel Kant, has taken an even more radical view. The modern view is that there is no demiurge, and that the universe is really ultimately chaotic.

Whatever order and meaning there is in the world has been imposed by human beings, and by no one else. We create our own worlds by generating our own worldviews. All meaning, all symbols, are man-made.’

This is a far cry from the rich musical archaeology of greats like Dylan and all those who appreciate what is truly given in this world. Including those inherited riches in the fields of music and literature.

For Jordan, ‘Symbolism, then, is not some secondary concern, some mere curiosity. In a very real sense, symbolism is more important than anything else for the life of man… the doctrine of creation means that every created item, and also the created order as a whole, reflects the character of the God who created it. In other words, everything in the creation, and the creation as a whole, points to God. Everything is a sign or symbol of God.’

He wonders, ‘How are we going to read these symbols? By guesswork?’ But finds, with Dylan, a firm foundation to build upon. A rock of ages. Both appreciate that ‘we have the Bible to teach us how to read the world.’ [43]

Our unknown and often unproven modern assumptions are called out by the perceptive poet, Dylan, who returns to a childlike wonder to enter the kingdom,

‘Yes, my guard stood hard when abstract threats too noble to neglect

Deceived me into thinking I had something to protect

Good and bad, I define these terms quite clear, no doubt, somehow

Ah, but I was so much older then I’m younger than that now.’ (My Back Pages) [44]

Our sense of who and where we are is turned upside down.

Jordan reminds us that, ‘Symbolism “creates” reality, not vice versa. This is another way of saying that essence precedes existence. God determined how things should be, and then they were.

God determined to make man as His special symbol, and then the reality came into being. Bavinck puts it this way: “As the temple was made ‘according to the pattern shown to Moses in the mount,’ Hebrews 8:5, even so every creature was first conceived and afterward (in time) created.’

He shows that, ‘Similarly, Man is a symbol-generating creature. He is inevitably so. He cannot help being so. He generates good symbols or bad ones, but he is never symbol-free. Man’s calling is to imitate God, on the creaturely level, by naming the animals as God named the world (Genesis 1:5ff. 2:19), and by extending dominion throughout the world.’

By attending to the reality of symbols, we are made free from the dizzying delusions of disorder; returning to right order and rewarded with the real world.

Again, Jordan calls us to, ‘Notice that naming comes first. Man first symbolizes his intention conceptually, and then puts it into effect. Symbols create reality, not vice versa.

Or, more accurately, for God, symbols create reality, for man, symbols structure reality. Man does not create out of nothing; the image of God’s creativity in man involves restructuring pre-existent reality.’

The grace of The Gospel transfigures the underlying structure of Halakhic Man and paves the way for the jester to become more than he was before. A priestly king and prophet in one. The times truly are a-changin’. [45]

‘Though you might hear laughin’, spinnin’, swingin’ madly across the sun

It’s not aimed at anyone, it’s just escapin’ on the run

And but for the sky there are no fences facin’

And if you hear vague traces of skippin’ reels of rhyme

To your tambourine in time, it’s just a ragged clown behind.’ (Mr Tambourine Man) [46]

Jordan unintentionally hints at the symbolic power of Jesus Christ in the music of Woody Guthrie and the gospel music young Dylan grew up with: ‘Grace gives us redeemed and restored men. The saved are re-symbolized as righteous and whole before God. Here again, we have two witnesses, the royal priesthood (believers) and the servant priesthood (elders).’ The road for the jester to enter the royal priesthood was set. [47]

Each of the key Judeo-Christian symbols informs Dylan’s entire oeuvre from the sixties until the twenty twenties and his we can see from Murder Most Foul that Bob’s vision is still clear.

Jordan focuses on three that we discover in Dylan over and again, ‘Books have been written on the interrelationship of the three special symbols: Word, Sacrament, Person. Here my point is simply this: These are the three special symbols God has set up. The restoration of the whole fabric of life takes place when these symbols are restored to power.’ [48]

The Disorder of Music and Popular Culture

Bob Dylan is a special figure of pop culture and has proven a unique phenomenon over the last half-century. He has remained free from the musical constraints above and below.

Once famously and ludicrously labelled Judas by ‘fans’ for ‘going electric’, he has refused to bend the knee to demands that come from the mob, or from the high fashions of the music industry. He has a story to tell and harmonizes order with non-order to play the way he has been called to play.

Let’s listen to philosopher Roger Scruton as he describes some of the pitfalls of popular culture and its music.

‘Popular culture is not a system of moral and religious belief, does not find expression in customs and ceremonies, is not induced through rites of passage, and is often enjoyed in solitude and without any essential reference to a community of initiates.’

Popular culture is missing the ‘We’ of Rabbi Sacks and the qualities that attracted the young Dylan to folk, Gospel and The Blues. Each of which were infused with the power of community and common purpose. From the common experience of black slaves in the southern United States or poor immigrants arriving in the nation’s north during hard times.

Scruton contends that, ‘It is therefore not a culture in the anthropologist’s sense at all, and its very fluidity and open-ness enable it to flow over all traditional forms of social order and to break down the barriers between them.

Pop music is now a globalising force, creating adherents wherever the air-waves can flow: ‘one world, one music,’ in the slogan adopted by MTV…’ [49]

The unique appeal of Dylan is that he can be so quintessentially American and yet so powerfully universal. This is a quality he shares with two of the twentieth century’s other premier formalist poets, Ireland’s Seamus Heaney and Poland’s Czeslaw Milosz.

Each of the three men have been given The Nobel Prize for their priceless contributions to their nation’s cultures and the world’s common reserve. Each has mastered the forms and known the true power of language used the right way, ‘knowing their song well before they started singin’.

Each lived through harsh times and embodied their nation’s collective struggles. With the pressure serving to create precious diamonds for their kin.

Scruton laments how, ‘Pop Culture is characterised by a peculiar feature, which I can only describe as the ‘externalisation’ of the musical movement.’

The spirit of the music doesn’t come from within, but from the spirit of the age and from fashionable demand. It is impersonal. This hurts the music and the lyrics.

Scruton continues, ‘Like music in our classical tradition, and like jazz, ragtime, blues and folk, pop has melody, rhythm, harmony and tone-colour.

But these seem to come not from within the music itself, but from elsewhere. The music is generated from a point outside, assembled from a repertoire of effects, according to procedures which involve little or no invention, but which set the music into a machine-like motion with repetition as the principal device.’

In an anti-human inversion of good music, Man begins to serve machines, the market, the musician’s ideology and what is ‘useful’ at the cost of true artistic integrity or the goodness of God’s creation.

Scruton continues by showing how this reflects the disorder or our present age, ‘In fact the externality of the movement is precisely what suits the music for its place in a society of overheard noise. The kind of music that I am describing might be called ‘music from elsewhere’ – it is churned out by the music machine and scattered on the airwaves. And this mechanical approach to the musical material serves a function.’

There is disharmony between Man and music, ‘When the voice is erased from the accompaniment, and re-processed as noise, the singer becomes the focus of attention. The music becomes the background to a drama, which is the incarnation of the idol.’ [50]

The power of Dylan lies in part precisely in his ability to point beyond himself, to keep our attention on the drama of the music and lyrics. And sometimes on characters he creates. Each composition is layered with rhythm, rhyme and complex narratives to claim our attention.

Bob offers ‘iconographic’ music to draw us into a grander symbolic world, creating and sometimes taking on characters to incarnate stories for the listener to share in. [51] He retains the humane honesty of the older musical and cultural forms. This is one of the key features of Dylan’s career. It can be seen in Scorsese’s No Direction Home, and Rolling Thunder Revue on Netflix, the latter based close to the time of what many consider his magnum opus Blood on the Tracks. That album portrays Dylan’s clear storytelling prowess.

Songs like Shelter from the Storm and Tangled up in Blue weave their way into the tapestry of Judeo-Christian civilization’s great art by virtue of Dylan’s humble and humane creation.

He makes many layered and complex cross-references to ‘high culture’, such as Dante’s poems of love in Tangled Up in Blue and delves low into the fertile fields of The Mississippi Delta to draw upon the Blues’ hopeful resistance against oppression and fate.

Scruton laments immature characteristics of pop music and their cultural counterpart where, ‘The external movement of modern pop connects with an important fact of modern life. The modern adolescent finds himself in a world that has been set in motion; he is beset by noise, by external pressures, and by forces that he cannot control.’

This disordered fatal empathy observes a distorted form in the carnivalesque mirror of the pop idol upon the secular altar:

‘The pop star is displayed in the same condition, high up on electric wires, the currents of modern life zinging through him, but miraculously unharmed. He is the guarantee of safety, the living symbol that you can live like this forever. His death or decay are simply inconceivable, like the death of Elvis.’ [52]

The chaotic ‘disorder’ of popular music, Jeremy Begbie demonstrates, has fallen far from the sweet neat sounds of older ‘orderly’ music, but we do not long nostalgically for the heavenly middle ages but for transfiguration of what is good and humane. Begbie assures us that the great canon of Judeo-Christian music contains creative ‘non-order’ and ‘improvisation’ within its range. [53]

Indian scholar Vishal Mangalwadi has compared Bach, Cobain and their worlds to express where music has fallen from earlier ages and how this reflects digressions in wider society. We could perform a similar comparison between Bob Dylan and many a pop music idol:

Mangalwadi affirms that, ‘Augustine taught that while this musical code is “bodily” (physical), it is made and enjoyed by the soul. For example, the book of Job deals with the problem of inexplicable suffering.

In it God himself tells Job of the connection between music and creation: “Where were you when I laid the foundation of the earth? . . . when the morning stars sang together, and all the sons of God shouted for joy?”

There is a healthy place here for music at the heart of ‘sacred’ life. Mangalwadi continues:

‘The Bible taught that a sovereign Creator (rather than a pantheon of deities with conflicting agendas) governs the universe for his glory. He is powerful enough to save men like Job from their troubles.

This teaching helped develop the Western belief of a cosmos: an orderly universe where every tension and conflict will ultimately be resolved, just as after a period of inexplicable suffering Job was greatly blessed.’

This helps us appreciate Dylan’s Judeo-Christian world, and the art it gives birth to.

Our Indian scholar shows us that, ‘This belief in the Creator as a compassionate Savior became an underlying factor of the West’s classical music and its tradition of tension and resolution. Up until the end of the nineteenth century, Western musicians shared their civilization’s assumption that the universe was cosmos rather than chaos.’

Because of the focus on Christ and His New Creation as the end, something we considered for Bob Dylan and NT Wright earlier,

‘They composed consonance and concord even when they experienced dissonance and discord. That is not to suggest that classical music did not express the full range of human emotions. It did.’

The entire drama of salvation was offered in Bach, Beethoven, Mozart and the masters of music, their forms centered around the source of life. The Living God of The Scriptures and His good creation inspired these men to reach new musical heights and break new ground. Dylan has returned to the same rock over his long career, over and again.

Mangalwadi sees this faith in the goodness of creation echoed in the emphasis on tonality:

‘For centuries, Western music was tonal. That is, its hallmark was loyalty to a tonic key/home note. Every single piece gave preference to this one note (the tonic), making it the tonal center to which all other tones were related.’

The move away from this strong center in music went hand in hand with moves towards new political ideologies and new desecrated centers.

He relates a fascinating piece of history for us to consider about the death of tonality in Judeo-Christian music: ‘The breakup of tonality in Western music is said to have begun with Adolf Hitler’s hero, Richard Wagner (1813–1883), who experimented with “atonality” in his opera Tristan and Isolde. Claude Debussy (1862–1918), Grand Master of the occult Rosicrucian lodges in France, took that experiment further.’

The quest to rebel against the real has continued to ramp up the chaos through the generations and claim it is good. Making chaos out of order to invert the creator of the cosmos.

Mangalwadi shows that ‘The West’s descent into the chaos of atonality accelerated in the twentieth century in Vienna, the capital of Europe’s cultural decadence.

Eventually the atonal composers had to create a new organization in their art to replace tonality—an artificial tonality called serialism. By dismissing tonality—the center—they lost something they hadn’t considered—form.’

Again, inverting Genesis so that the world of music was formless and void.

Mangalwadi returns to Cobain to make clear his point about the chaos and idolatry of much modern music, ‘Technically, Cobain retained tonality, but in a philosophical sense the loss of tonality in Western culture culminated in Cobain’s music, the icon of America’s nihilism and an unfortunate victim of a civilization that is losing its center, its soul.’ [54]

Not everyone can live with this chaos in music and life. The ‘formless void’ often proves too much and the number of suicides in the year of Covid-19 is a bleak mark on the new popular culture. Many seek new idols instead and live by orders from their race, social class, politicians or businessmen. This is a life not much better than death however and marks the low road to what Dylan describes in ‘A Pawn in Their Game.’

‘And the Negro’s name

Is used it is plain

For the politician’s gain

As he rises to fame

And the poor white remains

On the caboose of the train

But it ain’t him to blame

He’s only a pawn in their game.’ (A Pawn in the Game) [55]

Mangalwadi commends the consistency of Cobain who, at least, lived his beliefs out to their ‘logical’ conclusions:

‘It must be added in his defense that by killing himself, Cobain demonstrated that he lived by what he believed. His sincerity makes him a legitimate icon. Most nihilists do not live in the grip of what they believe to be the central truth about reality.

For example, French existentialists Sartre and Camus advocated choice despite the nihilism they embraced. In so doing they made a way out of Cobain’s problem. For them suicide was not necessary if one could create his own reality by choices.’

Amongst other things, Sartre and Camus could hardly have estimated the power of modern advertisers, as anyone au fait with pop music and culture knows. ‘Our choices’ are created for us and sold at a high price.

Mangalwadi suggests that, ‘Cobain remains popular because while many people claim to be nihilists, they don’t fully live it out. He did. He lived without creating his own reality through choice (or tonality through serial technique). He lived in the nihilism, in the “atonality,” and in that nihilism he died.’

It is here at this low ebb that we see how high Bach, Mozart, Dylan and the best musical artists have climbed and why they are so important for Judeo-Christian civilization. They bring us home to the high beauty, goodness and truth of life.

Mangalwadi’s caution against the nihilism that killed Cobain continues by meaningful comparison between order and chaos, life and death: ‘In that sense Cobain stands as the direct opposite of the life, thoughts, and work of J. S. Bach. Whereas Bach’s music celebrated life’s meaning as the soul’s eternal rest in the Creator’s love, Cobain became a symbol of the loss of a center and meaning in the contemporary West.’

He suggests, ‘While Western music has gone through dozens of phases with thousands of permutations since the time of Luther and Bach, in some ways it was only during the 1980s that a phenomenon like Kurt Cobain became possible.’

Mangalwadi, like Bob Dylan, tears down the false walls of separation between ‘sacred’ and ‘secular’, morality and music once more.

‘The rejection of a good, caring, and almighty God and a rejection of the biblical philosophy of sin ensured that there was no way to make sense of suffering—personal, societal, or environmental. Reality became senseless, hopeless, and painful.’ [56]

Dylan offers a new highway, neither returning in mere imitation of the former maestros, nor sequestered in the existential deceptions of nihilism.

Musician and theologian Jeremy Begbie’s shown us that there is a hope for ‘non-order’ and its play with ‘order’. By virtue of remaining centered on the real, Bob Dylan plays creatively with order and non-order to make music both ancient and new. [57]

Bob’s distinct voice is at the center of his work next to deep lyrics that can be heard and felt across ages. The layered sound of his songs echoes the great musical styles of folk, blues, gospel and the great canon.

The decidedly non-orderly Mr. Tambourine Man sings this truth beautifully,

‘And take me disappearing through the smoke rings of my mind

Down the foggy ruins of time, far past the frozen leaves

The haunted, frightened trees, out to the windy beach

Far from the twisted reach of crazy sorrow

Yes, to dance beneath the diamond sky with one hand waving free

Silhouetted by the sea, circled by the circus sands

With all memory and fate driven deep beneath the waves

Let me forget about today until tomorrow.’ (Mr. Tambourine Man) [58]

This is just a hint of Dylan’s worth. In a follow-up essay, we will look more at Bob as a literary master in line with a great tradition.

Notes

1- Dylan, Bob (2020) Murder Most Foul, Available at: https://www.azlyrics.com/lyrics/bobdylan/murdermostfoul.html (Accessed: 3rd April 2020).

2-Goring, Rosemary (2020) Why Bob Dylan is still the voice of our generation, Available at: https://www.heraldscotland.com/news/18349217.rosemary-goring-bob-dylan-still-voice-generation/ (Accessed: 3rd April 2020).

3- Dylan, Bob (2020) A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall, Available at: https://www.azlyrics.com/lyrics/bobdylan/ahardrainsagonnafall.html (Accessed: 2nd April 2020).

4-Ibid.

5- Ibid.

6- Ibid.

7= Ibid.

8- Ibid.

9-Genius (2020) Blowin’ in the Wind, Available at: https://genius.com/Bob-dylan-blowin-in-the-wind-lyrics (Accessed: 2nd April 2020).

10- Kierkegaard, Soren (2019) The Present Age: On the Death of Rebellion, USA: Harper Perennial.

11- (2008) The Orthodox Study Bible, USA: Thomas Nelson.

12- Schmemann, Alexander (2012) O Death, Where Is Thy Sting, USA: St Vladimir’s Seminary Press.

13- Ibid.

14- Ibid.

15-Plen, Matt (2020) Rabbi Soloveitchik, Available at: https://www.myjewishlearning.com/article/rabbi-soloveitchik/ (Accessed: 3rd April 2020).

16- Dylan, Bob (1965) Highway 61 Revisited , Available at: https://www.amazon.co.uk/Highway-61-Revisited-Bob-Dylan/dp/B006IXSH8K/ref=sr_1_1?crid=2DCCZ5UHFRR2A&dchild=1&keywords=highway+61+revisited+bob+dylan&qid=1585959198&sprefix=highway+61+rev%2Caps%2C148&sr=8-1 (Accessed: 4th April 2020).

17-Dylan, Bob (2004) John Wesley Harding Remastered , Available at: https://www.amazon.co.uk/John-Wesley-Harding-Bob-Dylan/dp/B0001M0KDE/ref=sr_1_1?dchild=1&keywords=john+wesley+harding&qid=1586016496&sr=8-1 (Accessed: 4th April 2020).

18-Netflix (2020) Rolling Thunder Revue, Available at: https://www.netflix.com/title/80221016 (Accessed: 3rd April 2020).

19-Fleming, Colin (2016) Remembering Bob Dylan’s Infamous ‘Judas’ Show, Available at: https://www.rollingstone.com/music/music-news/remembering-bob-dylans-infamous-judas-show-203760/ (Accessed: 3rd April 2020).

20-Ibid.

21-Piaget, Jean (1952) Play, Dreams and Imitation, Available at: http://web.media.mit.edu/~ascii/papers/piaget_1952.pdf (Accessed: 3rd April 2020).

22-Fruchtenbaum, Dr. Arnold (2017) Yeshua: The Life of Messiah from a Messianic Jewish Perspective, USA: Ariel Ministries.

23-The Dynamics of Transformation (2013) Bob Dylan’s Transfiguration, Available at: https://rockandrollphilosopher.wordpress.com/2013/06/26/bob-dylans-transfiguration/#_edn5 (Accessed: 3rd April 2020).

24-Jones, Rebecca (2011) Dylan tapes reveal heroin addiction , Available at: http://news.bbc.co.uk/today/hi/today/newsid_9492000/9492886.stm (Accessed: 3rd April 2020).

25-Rolling Stone (2019) The 27 Club: A Brief History , Available at: https://www.rollingstone.com/culture/culture-lists/the-27-club-a-brief-history-17853/robert-johnson-26971/ (Accessed: 3rd April 2020).

26-Dylan, Bob (2020) No Time to Think, Available at: https://genius.com/Bob-dylan-no-time-to-think-lyrics (Accessed: 4th April 2020).

27-Premier On Demand (2019) NT Wright sings Dylan’s ‘When The Ship Comes In’ // Ask NT Wright Anything, Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=s88amVh4RZA (Accessed: 4th April 2020).

28-Dylan, Bob (2020) When the Ship Comes In, Available at: https://genius.com/Bob-dylan-when-the-ship-comes-in-lyrics (Accessed: 4th April 2020).

29- Wright, NT (2020) History and Eschatology Jesus and the Promise of Natural Theology , Available at: https://spckpublishing.co.uk/history-and-eschatology (Accessed: 3rd April 2020).

30-Beale, G.K (2008) We Become What we Worship: A Biblical Theology Of Idolatry, USA: IVP.

31-Lasch, Christopher (1994) The True and Only Heaven: Progress and Its Critics, USA: W. W. Norton & Co..

32-Lewis, C.S. (2012) Mere Christianity, USA: HarperCollins Publishers Limited.

33-Middleton, J. Richard (2014) A New Heaven and a New Earth: Reclaiming Biblical Eschatology, USA: Baker Academic.

34- Ibid.

35- Ibid.

36- Sacks Jonathan, Rabbi (2020) Morality: Restoring the Common Good in Divided Times, Available at: http://rabbisacks.org/morality-restoring-the-common-good-in-divided-times/ (Accessed: 3rd April 2020).

37-Boehlert, Eric (2000) Dylan’s “Hurricane”: A Look Back , Available at: https://www.rollingstone.com/movies/movie-news/dylans-hurricane-a-look-back-248581/ (Accessed: 3rd April 2020).

38- Ibid.

39- Ibid.

40-Pageau, Jonathan (2020) The Symbolic World, Available at: https://www.youtube.com/user/pageaujonathan (Accessed: 3rd April 2020).

41-Dylan, Bob (2020) Forever Young, Available at: https://www.bobdylan.com/songs/forever-young/ (Accessed: 3rd April 2020).

42-Genius (2020) Jesus Christ (They Laid Jesus Christ in His Grave), Available at: https://genius.com/Woody-guthrie-jesus-christ-they-laid-jesus-christ-in-his-grave-lyrics (Accessed: 3rd April 2020).

43-Jordan, James B. (2019) Symbolism and Worldview, Available at: https://theopolisinstitute.com/symbolism-and-worldview/ (Accessed: 3rd April 2020).

44-Dylan, Bob (2020) My Back Pages, Available at: https://genius.com/Bob-dylan-my-back-pages-lyrics (Accessed: 4th April 2020).

45- Dylan, Bob (2020) The Times They Are A-Changin’, Available at: https://www.bobdylan.com/songs/times-they-are-changin/ (Accessed: 3rd April 2020).

46-Dylan, Bob (2020) Mr. Tambourine Man, Available at: https://genius.com/Bob-dylan-mr-tambourine-man-lyrics (Accessed: 4th April 2020).

47- Ibid.

48- Ibid.

49- Scruton, Roger (2020) The Cultural Significance of Pop, Available at: https://www.roger-scruton.com/about/music/understanding-music/175-the-cultural-significance-of-pop (Accessed: 2nd April 2020).

50- Ibid.

51- Hart, Aidan (2012) Designing Icons (pt.1), Available at: https://orthodoxartsjournal.org/designing-icons-pt-1/ (Accessed: 3rd April 2020).

52- Ibid.

53- Begbie, Jeremy (2009) Theology through the arts, Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UlR3bOsoAdA (Accessed: 2nd April 2020).

54-Petersen, Jonathan (2015) How the Bible Created the Soul of Western Civilization: An Interview with Vishal Mangalwadi, Available at: https://www.biblegateway.com/blog/2015/07/how-the-bible-created-the-soul-of-western-civilization-an-interview-with-vishal-mangalwadi/ (Accessed: 2nd April 2020).

55-Dylan, Bob (2020) Only a Pawn in Their Game, Available at: https://genius.com/Bob-dylan-only-a-pawn-in-their-game-lyrics (Accessed: 4th April 2020).

56-Ibid.

57-Ibid.

58-Ibid.

Additional Notes

-Dylan plays with time, in a playful non-order which is intentional and layered. This is not the same thing as disorder. Disorder equals chaos. Non-order equals improvisation.

-Dylan learned how to paint many years ago so he could think in images where many different impressions are being made at once. This is a feature of his work, which moves between past, present and future to draw the listener into another world. A world free from one-dimensional, and linear, thinking and acting. I have tried to paint a sketch of his work by following the master’s technique.

-I use Man to represent humankind where possible as I think the points made should speak to women and men (Or intersex) in equal measure.

This is the first of three parts with parts two and three available.