Nietzsche – The Diabolical Saint of Acceptance

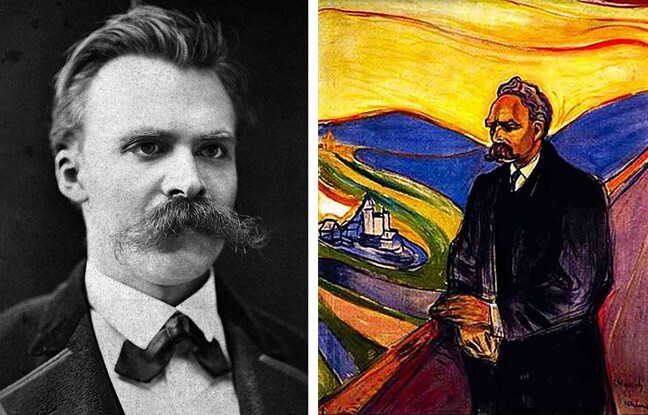

Friedrich Nietzsche is a strange mixture of conflicting impulses; so chronically sick that writing was a physical agony for his eyes and his stomach permanently bothered him, yet he wrote paeans to the strong and mighty. A brilliant analyst of resentment, he had every reason to feel ignored being unread during his lifetime and self-publishing books that he mostly could not sell. He admired Dostoevsky, which itself is admirable, writing in Twilight of the Idols that Dostoevsky was the only psychologist from whom he had anything to learn. Nietzsche first stumbled upon Dostoevsky’s Notes from Underground in a bookstore in Nice in the winter of 1886-87 and immediately loved it, though Dostoevsky never knew of Nietzsche. Notes from Underground is psychologically and anthropologically penetrating, exploring themes of mimesis and resentment that were of immense interest to Nietzsche.

Unlike Dostoevsky, there is something perennially adolescent about Nietzsche, perhaps because young adults are often trying to decide what values they should hold, often temporarily in contradiction to their parents, as they prepare to make their way in the world on their own. Nietzsche’s “transvaluation of values” fits this model nicely. There used to be a certain kind of young man magnetically drawn to Nietzsche’s mixture of cleverness, perversity, sense that he had a secret understanding of things, and man alone and against the world demeanor, and perhaps there still is.

God is ultimately the source of all value. It is because we are made in the image of God and are thus connected with eternity, God, and Freedom that the Person has supreme intrinsic value. There simply is no way around this fact. Nietzsche, on the other hand, is famous for the notion that God is dead. This is usually understood to mean that God is dead as a cultural phenomenon; that all the smart people have become atheists. René Girard argues in Dionysus Versus the Crucified, however, that this is a misunderstanding and that the truth is far more complicated. Nietzsche rejected Christianity in favor of a return to pagan religion and Dionysus. Dionysus is a trickster god who stirs up trouble, encourages his own murder by challenging the social hierarchy, only to magically reappear unharmed afterwards. This is because Dionysus represents the scapegoat who is falsely blamed for generating a complete social breakdown in a way that only a god could achieve, who is then murdered, bringing the community together in shared hatred, unanimity minus one, and is then credited with creating widespread peace, again in a god-like manner. The Bacchae by Euripides, “Bacchus” being another name for Dionysus, depicts the threatening, implacable, and undefeatable nature of the scapegoating dynamic. Dionysus, a long-haired beautiful and effeminate youth, has a reputation for stirring up the Bacchae, the female followers of Bacchus, into a mad murderous frenzy that would likely include wild drinking. Pentheus, the king of Thebes, wants nothing to do with Dionysus and tries to eject him from the city but, failing that, ends up imprisoning him. Dionysus warns Pentheus that he will be sorry for interfering with a god, an earthquake sets Dionysus free from his prison, and everything goes to hell for Pentheus who loses his head, literally, at the hands of his own mother who has become one of the bacchants.

Nietzsche rejects the Christian God of compassion, and opts for the pre-Christian Dionysus who is killed and then revives. God is dead, long live God. Dionysus dies that we may be saved over and over again. The strong murder the weak; and the mob are always stronger than the individual, as Socrates points out in The Gorgias, much to the disgust of Callicles. Nietzsche sides with Callicles in praising the strong, but his position suffers from the same defect. The many, the rabble, can beat the few. Nietzsche then finds himself in the ludicrous situation of defending the strong against the weak, a logically and rhetorically contradictory position. In Christianity, as Nietzsche sees it, the slaves have risen up against their masters and denounced brutality, praising forgiveness and compassion, tricking the strong, the masters, into feeling guilty for callously mistreating their social inferiors. Nietzsche is correct that the weak are prone to resentment, that unlovely emotion and attitude, but it is better than the strong’s treatment of the weak. Repressed violence is better than violence expressed.

Unlike many nineteenth century anthropologists and critics who equated the savior aspect of Dionysus and other sacrificial religions with Jesus’ death, Nietzsche recognized that Dionysus is the antithesis of the Crucified. The immolation of Jesus reveals the scapegoat mechanism because he is recognized as an innocent victim murdered at the hands of the mob. Up until then, this habit of murdering the scapegoat went unnoticed partly because the victim was not alive to complain about his unjust treatment. With Jesus, the disciples were steadfast in maintaining Christ’s innocence with supernatural courage, since defending the scapegoat puts someone at odds with the mob who are likely to treat him with the same rough justice they meted out to the victim. So, Nietzsche had enough insight to recognize what made Jesus different.

Thus Spake Zarathustra is where Nietzsche announces the death of God and has the prophet claim that we have murdered him with our bloody knives. Girard points out that this is simply not taken seriously by many critics who imagine that he is referring to the Christian God and that the reference to knives is strictly metaphorical. But it is Dionysus the god, the scapegoat victim, that we kill with our knives whereupon he is resurrected as immortal savior, to begin the process all over again.

In Habits of the Heart by Robert Bellah, et al., Bellah is mystified by the trope of the lone cowboy who comes to town, saves it from whatever is threatening it, and then rides off into the sunset. Bellah raises two questions; what is the cowboy’s motivation for saving the town? He seems to be a loner with no ties to the community, so the impetus for helping the townspeople seems lacking. And then, having saved everybody and earned their gratitude, why does he not settle down, marry the schoolteacher, and take up residence? He would likely be a popular townsman. Why does he vanish, never to be seen again?

The answer is simple. The cowboy is Dionysus, the perennial scapegoat victim, the god we kill with our long knives. His is a saving presence because the townspeople can cease warring against each other, for instance, the cattle men versus the homesteaders, and gang up on him. His lynching solves their problem short term. His coming to town is retrospectively seen as the key element in producing peace. The cowboy disappears from the scene because he is dead. He is gone, but his replacement and doppelganger, fulfilling exactly the same role, will turn up in another town, or even the same town at a later date. Thanks, Lone Ranger. You’re always there when we need you!

Nietzsche wants a transvaluation of all values, but since the Christian God is the source of all value and Nietzsche is an atheist, he is unable to generate value at all. What he calls “master” morality in The Genealogy of Morals is the absence of morality. It is in line with Callicles’ description of the strong who simply take what they want. Here Callicles uses the demi-god Heracles (Hercules in Latin) as his example, swooping in to take another man’s cattle. The fact that Heracles is half-god is relevant. Heracles, the man who murdered his whole family and thus is the arch-villain scapegoat victim, also plays savior as the most heroic of all Greek heroes. One thing Nietzsche claims to like about the “masters” is that they do not hate or resent anyone. They have no envy and anyone below them socially is unworthy of their attention. They have eyes only for their social equals with whom they might compete, but who they also respect. The weak are simply beneath contempt.

Nietzsche is concerned that Christianity and the morality of his time were a kind of cult of equality and thus mediocrity. Rather than admiring the cultural high achievers, like himself perhaps, Nietzsche worried that it was the meek, the humble, and most of all, the innocuous, who were esteemed. Many of Nietzsche’s criticisms of Christianity are really attacks on the Christianity of his time which had many unappealing features. He certainly was not a fan of boring bourgeois sentimentality or the idea of eternal damnation. The difficulty is that there is no way to get value from a Godless, naturalistic, view of reality. So, Nietzsche is reduced to impotency. He wants an alternative to values derived from theism, but is noticeably and initially perplexingly unenthusiastic about “master” morality. His heart was not in it. Mastery morality seems to play the role of a place-filler until he can come up with something better, but of course, he never does and he just flails around.

Nietzsche rejects the boring, mediocre, and banal aspects of the morality and religion of his time, but then he accepts the equally boring and banal aspects of scientifically inspired metaphysics, naturalism, also popular in his era. This is a total failure of imagination. But it also represents a genuine dichotomy. Once a belief in the Kingdom of God, of heaven, the transcendent, and the divine is abandoned, what is left is mere physical reality, and physical reality as a sequence of events is deterministic and thus meaningless and unlovable. It is only when some of those events point back to their origins in the spiritual realm of subjectivity, and thus agents, that determinism can be escaped.

What Nietzsche needed to do was to criticize socially-derived malformations of Christianity and replace them with a more genuine Christian vision. This can be difficult because science and religion as social phenomena have the great mass, Das Man, backing them up. This creates orthodoxy and makes of the free thinker a heretic. Nietzsche’s acquiescence to many scientific tropes is surprising given his iconoclastic attitude to religion. Clearly religion and myth inspired his imagination more than science did. Dostoevsky’s character Ivan in The Brothers Karamazov at least criticizes a very sophisticated version of Christianity and attacks it well, despite Dostoevsky’s pro-Christian sentiments.

To understand what is going wrong with Nietzsche’s thought it is necessary to understand Ken Wilber’s argument that the proper existential stance requires both wisdom and compassion, Eros and Agape, symbolized by the allegory of Plato’s Cave. In leaving the cave, the philosopher, the lover of wisdom, is searching for wisdom, salvation, God, the Good, and happiness. For Plato, happiness requires wisdom because it is necessary to learn the difference between what is truly desirable and what is not. Part of man’s destiny is to develop. Misery and suffering will lead to wanting to overcome the problems and limitations that cause these things. The quest to understand the Good better is everyone’s life long goal, whether they know it or not.

So, to care about yourself and for other people, it is necessary to strive to develop and to wish them to do so as well. To wish anyone to stop developing at any age is to wish him ill. The interests and limitations of a ten-year old are fine when he is ten, but ridiculous when he is fifteen. But a proper existential stance also requires compassion. Compassion is acceptance; unconditional love symbolized by returning to the cave out of concern for the philosopher’s fellow prisoners.

Wilber calls the quest for development and improvement “Eros,” related to the love man has for God, and equates it with a more masculine-style conditional love, and unconditional compassionate love he calls “Agape,” the love God has for man, which he regards as being more nurturing and feminine in nature. He argues that both Eros and Agape are necessary for either one to exist properly and thus that each individual should embody both of these tendencies. Traditionally, the proper raising of a child entails a father demonstrating an Eros form of love, pushing the child to develop and setting standards, and a mother who loved her child unconditionally no matter what wrongs he might commit, loving all her children equally. Men and women can play both roles as needed, though boys without actual fathers are statistically more likely to end up being violent, drug or alcohol addicted, and to have worse vocational and educational achievements.

The quest for development can be taken too far. Puritanism and Gnosticism strive for salvation only and regard the body and physical reality as evil; as a nasty hindrance barring the way to happiness. Sparta represents an example of a culture that over-emphasized Eros. The Spartans, driven by fear of an uprising by the Helots, the usually Greek slaves they kept that far out-numbered them, embraced a very brutal, friendless, social existence designed to generate the ultimate warriors. They represent a very Eros-only form of life. A Spartan mother is supposed to tell her son to come back either with his shield or on it.

The urge for compassion and acceptance can be overdone as well. Fertility Cults unconditionally accept nature just as it is, and, incidentally, practiced human sacrifice. Culture can come to be seen as life-denying. To strive to develop is regarded as rejecting reality as you find it. However, since failing to develop is failing to live well, this excessive compassion in isolation is bad. Idiot compassion, as Wilber calls it, involves accepting everything with no urge to develop. A parent gives his kids candy and TV because “it’s what makes them happy.” One spouse allows the other to beat him up because he loves her. Medals are given for just showing up, Valentine’s Day cards are given by school children to every single classmate, rendering the cards meaningless, and children are told “good job” when the activity was not done well at all. Compassion without wisdom is not compassionate and caring at all. Instead it hurts people.

The traditional two parent family had the tough love Dad making the child do his homework and piano practice, sending him to bed with no supper if necessary, and the unconditionally loving mother sneaking him something to eat late at night. Genuine love involves complete acceptance of your children no matter what. Even if they become ax murderers, the parent will visit them in prison. It also involves pushing them to develop their talents rather than becoming useless to themselves and to other people.

Nietzsche goes wrong in his philosophy by being half right. A major problem and source of error involves mistaking a partial truth for the whole truth.[1] It is often difficult to extricate ourselves from this error because the thing that is being emphasized is true. The person knows he has hold of a truth and will not relinquish it. This is part of Nietzsche’s problem. He knows that compassion and acceptance are good and he is willing to promote them to the utter demise of compassion and acceptance! But he is also driven to this partiality through his metaphysical commitments. Nietzsche says there is no heaven, no transcendence. There is nothing higher to aim for. What is real is here on Earth and what we see is nature. Thus, there is no way to exit Plato’s Cave and nowhere to shoot for. This forestalls the possibility of Eros.

At times, Nietzsche longs to escape the human condition, existing in the metaxy; between God and animals. He fantasizes about the Übermensch, the beyond-man, the over man, the superman, breaking free from the herd, the mediocre, who would create his own values. However, if God is the source of value, then the Übermensch is impossible. Man creates value only through the conditions God the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit (Ungrund) provide. For one thing, without the transcendent, determinism reigns, and thus there is no creativity of any kind, no agents as centers of feeling, thinking, willing decision-making, because Freedom would not exist. Man as the image of God is partly free and creative and embodies supreme value in himself. That value is not created by him, but once so endowed, he can provide his own meaning to his endeavors.

Eternal Recurrence

Nietzsche, unlike the weak and slave-like people he despises, wants to say yes to life. His test for whether someone is saying yes to life is whether he would assent to an imaginary scenario. Do you assent, in principle, to living the same life you have just lived over and over again for all eternity without changing anything at all? If the answer is “yes,” then you are a saint of acceptance. Total acceptance means saying yes to life in all its aspects and mistakes.

It should be pointed out that Nietzsche definitely did not believe in actual reincarnation. This idea of eternal recurrence is just a thought experiment to determine a person’s fundamental attitude to life. The question is how someone reacts to the mere thought of this situation. This is where the partial truth enters. It can sometimes seem nice to fantasize about editing our lives; taking out all the boring bits, and the suffering and the times we acted badly. But saying yes to life is accepting it just as it is. However, what the test of eternal recurrence misses is embracing development; the striving part. Living the same life over and over would be a kind of hell because a person would never get to develop. A good life combines development and acceptance. In abandoning development, it is Nietzsche who is rejecting an important aspect of life.

Suffering is fine, as far as it goes. Suffering is a motive to change, to grow and develop. New parents must develop new capacities for patience or end up abandoning or murdering their new baby. However, the kind of suffering Nietzsche is recommending – never learning from your mistakes and thus never developing, is hell. Developing does not mean the end of suffering. Old problems are solved and new developmentally appropriate ones replace them. There are the problems of youth, of mid-life, and of old age; getting an education and useful skills at one point, managing a household at another, and finding a way of having a fulfilling retirement at yet another.

Acceptance is a virtue. We should accept two-year olds, for all their limitations. They cannot read, or write; they may not even be toilet trained, but they may still be a perfect little two-year old. We are all at some level of development and are perfect in this way too. But loving that two-year old also means not condemning them to the same mistakes, the same interests, the same level of cognitive development, for all eternity. In some sense, we are all that two-year old. By trying to say yes to life, Nietzsche says no to life.

What does Nietzsche see in nature? No morality. The strong eat the weak. It is brutal, but it is the way it is. For Nietzsche, morality says no to life. Morality tries to uplift the weak, it says that lending a helping hand is the moral thing to do. Nietzsche argues that morality says no to life, to nature. Any attempt to change these basic facts of life is to say no. We must say yes, and saying yes means accepting everything. Nature is on the side of the strong, so we should be too.

Those driven by excessive compassion, Agape, are sometimes attracted to Nietzsche’s nonjudgmental acceptance. Fans of Eros can admire Nietzsche’s emphasis on strength, independence, and self-reliance in this image of things, where a person is not looking for handouts or support from others.

In reality, Nietzsche’s view even of nature is inaccurate. “Nature” features animals working together for mutual survival, both prey and predator. Mother lions, birds, pandas, wildebeest, etc. care for and nurture their young. It is not all unrelieved brutality.

There is a certain type of smart, young person who thinks that accepting total nihilism is manly and admirable. Any deviation from unrelieved awfulness is seen as mere escapism and fantasy. Ivan Pavlov wrote: “There are weak people over whom religion has power. The strong ones – yes, the strong ones – can become thorough rationalists, relying only upon knowledge, but the weak ones are unable to do this.”[2] Since rationalism can only analyze, but not create value, beauty, and love, only the weak, in this view, will avoid nihilism. In addition, Pavlov falsely assumes that empiricism produces knowledge but that philosophical and religious speculation do not. Near unanimous agreement about the trivial is often possible, while important truths remain debatable, and this provides the opportunity for human creativity, imagination, intuition, and freedom.

Evidence of Nietzsche’s acknowledgement of the horror of what he is arguing and his willingness to accept this horror can be seen in his comments about Indian “untouchables;” the lowest members of the Indian caste system. They can wear only used clothing. They may not wash in fresh water because they would pollute it. They may drink only from the water that fills where the muddy hoof print of an animal like an ox has fallen. Nietzsche pretends to delight in this, after going into graphic disgusting detail. Cultural relativism, that instance of idiot compassion, would acquiesce to this. “This is the Indian way, we must not judge.” Unconditional acceptance. And paradoxically, this attitude might be attractive to lovers of excessive Eros, seeing the untouchables as the weak who get what they deserve.

Nature, Nietzsche thinks, says yes to “master” morality while Christian charity is keeping mankind down. Nietzsche claims that Kant celebrates mediocrity and bourgeois virtues like punctuality as though they are the peak of human achievement. If mankind is to achieve anything, Nietzsche thinks, it must leave the heaving masses behind and the true genius must rise above the petty self-protective whining of hoi polloi. The Übermensch will prevail.

Callicles, that Platonic character who inspired Nietzsche, might be right that generally the many, the weak, are fans of “justice” as law-abidingness because laws against stealing, violence, and murder protect the vulnerable more than those able to defend themselves. Their motives are often selfish, not moral. The weak hope for protection under the law, and value charity because they hope to be its recipients. Much of the time their apparent love of morality is just self-interest. This may well be true. But their selfish motives do not mean that kindness, charity, and laws, are wrong. It is possible to love genuinely good things for the wrong reasons.

Nietzsche, the diabolical saint of acceptance tries to accept everything as a consequence of unconditional love. But when he tries to accept Nature, he one-sidedly finds a charnel house of death and destruction, the strong consuming the weak. Out of love and compassion he will send the weak to the gas chambers and deny their pleas for help because in not accepting their fate, the weak are rejecting life. They must be shown the light. Those who seek to protect the weak he regards as the naysayers.

One senses, at times, Nietzsche’s reluctance to keep following this line of thought. He is going to overcome his disgust at brutality in a heroic act of acceptance. It is his idiot compassion that leads him to embrace ruthless domination and name Napoleon as a hero. Like some kind of wannabe savior, Nietzsche takes on the weight of the world. In his desire to supplant God and Jesus and to get people to embrace godlessness, Nietzsche strongly resembles Dostoevsky’s character Kirillov in The Devils, also known as The Possessed. Both become the rivals of God and Christ. They will save us from salvation, unredeem redemption and promise us eternal death. To do this, we must embrace our own nothingness and give up dreams of the divine; except the transcendental vision remains intact because to do this would be an immense overcoming. Nietzsche and Kirillov are grandiose in their aspirations and retain strong intimations of religiosity. Zarathustra is a prophet after all. They are as god-fixated as any theist. Apparently, Kirillov confused critics because he has many of the same virtues as Dostoevsky’s Christ-like Prince Myshkin in The Idiot. But Dostoevsky did this to show that truly demonic behavior can arise from the best of intentions.

Kirillov points out that the major draw card of religions is the promise of eternal life. No billionaire can offer such a thing. Kirillov hopes to overcome the fear of death through his suicide. If death is not to be feared, then religion becomes that much less attractive. Kirillov is in competition with Christ. Nietzsche is too and in fact is quite indignant about his inferior status. It seems likely that now, at least for some people, Nietzsche is indeed to be preferred to Christ.

Nietzsche can be compared to a naïve well-meaning undergraduate moral relativist. Relativism is taught to school children to teach them to be tolerant. Students will at times attempt to tolerate some of the greatest horrors ever perpetrated by mankind in order to be good people. They too, like Nietzsche, strive to be saints of acceptance and they do so by holding their noses and attempting to embrace slavery and the Holocaust. It is, however, evil to tolerate evil. Apparently, some of the children’s teachers who promulgate this rot actually promote this kind of thinking. An English teacher in Oswego, New York, teaches her classes that child slavery in Ghana is morally permissible, in the name of cultural sensitivity.

Nietzsche can at times be an excellent psychologist and aphorist. His claim that each person’s philosophy is a kind of self-confession is trenchant. He was right to be horrified by John Stuart Mill and utilitarianism, and by Kant, to a much lesser degree. However, he shared their rejection of Christian morality and imagined, like them, that he could improve upon it – but his beyond-man, his Übermensch, never did arise and produce new solely self-created values. Nietzsche’s naturalistic metaphysics precludes the attribution of value or the discovery of it because without God there is nihilism; nothing. The materialist and atheist Karl Marx also tried to supplant Christianity, but just borrows Christian compassion and charity, but distorts it by making it compulsory. Goodness only exists, is only good, if it is free.

Nietzsche finds some appropriate targets of nineteenth century bourgeoise morality and Christianity to criticize but does not come close to finding any alternative. At the most, Nietzsche can be seen as a truth-seeker and someone willing to accept unpleasant realities, but in the end his philosophy fails amid a mass of contradictions.

Notes

[1] Many truths are partial, but some more damagingly so than others.

[2] https://ffrf.org/component/k2/item/14872-ivan-pavlov