Nurturing the Historical Imagination: Teaching History within the Liberal Arts

The study of history is a rigorous intellectual enterprise. A student researching and writing about the past must sift through multiple pieces of evidence, grasp an event’s larger context, and think logically in order to construct arguments presenting plausible explanations as well as judgments and interpretations. But history is also an imaginative endeavor as practitioners of the discipline must oftentimes speculate about the past, especially when they deal with inconclusive and even contradictory pieces of evidence, or confront attitudes and viewpoints alien to our 21st century perspectives. Therefore, historians committed to the liberal arts have a responsibility to develop their students’ ability to vividly – and accurately — imagine a time other than their own.

A keen understanding of history is essential for all liberally-educated individuals for other reasons. It helps us to appreciate complex civilizations, recognize change over time, and comprehend the profound connections between past and present. Furthermore, knowledge of the past – particularly of our own history — is crucial for good citizenship: it contributes to our moral and ethical understanding of American society, provides identity, and helps us to comprehend the cultures and actions of different nations. Thus, an ability to envision the past in a critical and truthful manner becomes even more important.

Most of the students enrolled in college-level history courses today, however, typically possess only a dim understanding of the past. Much of what they have learned is from television, particularly from such insubstantial TV outlets as the History Channel and Military History Channel. Their programming not only focuses overwhelmingly on Hitler, Nazis, and/or the occult, their shows present simplistic and sometimes inaccurate accounts of highly complex historical events (oftentimes, however, with dazzling imagery). Therefore, students today have even less understanding of the past than their peers did several generations ago and they certainly lack the ability to “think historically” – that is, to grasp that people of the past were profoundly different from people today in terms of values, ideas, motivations, and perspectives.

How then should an instructor of history help a student to grasp the richness and complexity of the past? How should one help a student understand the changes and continuities between the past and the present? Finally, how should a teacher try to develop within a student a life-long love of the study of history so that he or she will continue to look to the past for lessons and meanings in our own age? Should an instructor try to turn students into individuals like Ralph Pendrel, the historian in Henry James’s novel The Sense of the Past? Pendrel is a character who desperately wanted to experience the past in the fullest possible way. Indeed, James wrote that Pendrel:

“. . . wanted the unimaginable accidents, the little notes of truth for which the common lens of history, however the scowling muse might bury her nose, was not sufficiently fine. He wanted evidence of a sort for which there had never been documents enough or for which documents mainly, however multiplied, would never be enough.”

To achieve this level of intimacy with the past, the novelist actually transported Pendrel from his own era, 1910, back to the year 1820. As a result, the historian truly relived the past in a tactile and immediate manner. As James wrote, Pendrel “feels” for himself “the stopped pulse” of that bygone age.[1] Therefore, should teachers of history attempt to whisk students back in time so they can relieve the past for themselves?

To a certain extent, the answer is yes – it is necessary for history teachers to transport their students back in time – at least to transport their intellects and imaginations back through the ages – so that they gain a richer and more complete understanding of the ideas, experiences, emotions, and motivations of historical actors. Of course, students must develop more than an antiquarian’s interest in and understanding of history. They must also be equipped with essential tools of investigation and critical analysis in order to derive the fullest insights into the past eras into which they are immersed. Creating this multidimensional understanding of history among liberal arts students strengthens their comprehension of the discipline as well as inspires them to return to history after they leave the classroom.

But how should a professor go about accomplishing this feat? This paper explains several specific approaches and strategies to teaching history designed to engage students on different levels; but all of them are especially meant to cultivate their historical imaginations or, in other words, to help them develop a “historical habit of mind.” I particularly focus on three methodologies: 1) creating an accessible narrative structure within my classes, 2) placing historical events in the widest possible context so that students can derive the fullest possible meanings from the information they learn in lectures, readings, and discussions, and 3) design interesting and challenging critical-thinking exercises which familiarize students with primary sources and force them to probe historical events and their meanings more deeply and substantially.

“Telling Stories”: The Narrative Approach

In recent years, many historians have eschewed the narrative format when teaching students, arguing that such an approach is simplistic and even “mere story-telling”. They have instead focused on a topical approach to teaching – an approach that gives little attention to chronology and much consideration to the various constituent subjects within a particular time period. Many professors also concentrate on creating “student centered” classrooms where students themselves largely lead discussions on various topics and are encouraged to come to their own conclusions about particular people and events. Perhaps not coincidentally, the historical literacy of U.S. college graduates has substantially declined over the last several decades. Believing that a strictly topical-approach to history courses as well as the “student centered” classroom are deleterious to students’ understanding, I employ a narrative structure in my courses which pays considerable attention to chronology, stories, and accessibility. The format, I contend, actually enhances students’ historical knowledge and increases their ability to process complex bodies of information.

History is often referred to as an endless jumble of facts. Sometimes history is even considered to be, as Arnold Toynbee once jokingly put it, just “one damned thing after another.” However, as the philosopher and historian R.G. Collingwood asserted in his book The Idea of History(1946), historical facts are inert or “dumb” things – that is, they have no intrinsic meaning in and of themselves. They gain importance and significance only when scholars interact with them and place them together into some sort of comprehensible framework. In order to nurture students’ historical imaginations and to create a life-long love of the discipline (essential for any liberally-educated person), I believe that professors should reconstruct historical facts into narratives that emphasize chronology, individual agency, and accessible stories. Indeed, such an approach is one of the most effective ways to engage students and improve their comprehension. Jerome Bruner’s work on this subject is particularly helpful in understanding the potential of the narrative to help students learn and intellectually develop. In his seminal 1991 Critical Thinking article, “The Narrative Construction of Reality,” Bruner asserts that “. . . narrative comprehension is among the earliest powers of mind to appear in the young child and among the most widely used forms of organizing human experience.” Therefore, because it is a broadly accepted means of “constructing and representing the rich and messy domain of human interaction,” students often innately take to it.[2]

In its simplest terms, a narrative history lecture describes the unfolding of a series of particular events which occur over a specific period of time. Because the human condition is so varied, the instructor must pay a great deal of attention to the motivations of the historical actors: what intellectual and social ideas, religious beliefs, etc. impelled or compelled them to act as they did? A lecture structured in the narrative format also typically presents the “whole story” about a particular topic to students. In my upper-level course on the American Revolution, for instance, I give a lecture on the war’s final major military operation, the Yorktown campaign of 1781. The campaign’s “whole story,” however, is composed of many constituent elements, including numerous economic, political, and military events leading up to the operation as well as those that occurred during the campaign itself (i.e., the various strategic and tactical moves by both sides as well as the particular actions of the officers and soldiers). When I wrote this lecture, I had to ensure that all the constituent parts selected for inclusion within it functioned in a correct and constructive manner. Indeed, they had to help students grasp not only why and how the final military campaign of the Revolution occurred on the Virginia tidewater in 1781, but they also had to explain the event’s larger context and why Yorktown was important and significant in the late-eighteenth-century as well as remains important 229 years later in 2010. In short, a well-crafted narrative lecture provides students not only with the accurate facts, but it also draws the clear conclusions as well as reasoned connections between past and present.

All narratives, furthermore, must be constructed with the background knowledge of the students taken into account. A wonderful lecture that is informative and insightful, yet beyond the understanding of a class of freshmen, accomplishes little. In fact, such a lecture may even engender to worst of all possible outcomes – creating a belief in students that they are incapable of mastering the subject, or that the subject itself is meaningless — hence their effort is not worth the candle. When I teach the American Revolution to my students in the United States survey, I naturally assume that their background knowledge is weaker than the upperclassmen in my Revolution course mentioned above. Most of these latter students typically have had several college-level history courses completed by the time they walk into my classroom. Therefore, for these more novice students, I carefully construct a narrative that is straightforward, direct, and thorough. A good instructor must also include compelling anecdotes that pique students’ interests, spark their imaginations, and make the material more memorable and engaging.

In my freshman survey, for instance, I relate in some detail the plight of African-American slaves trapped with Cornwallis and the doomed British garrison. The fate of these several hundred runaways was uncertain at best in October 1781 after the British surrender. The slaves had risked everything for a chance at freedom, yet the gamble had proven to be a poor one. Many slaves had caught dysentery and other camp diseases while in the British garrison and thus were dying when the campaign ended. Many other survivors openly wept when brought before their American masters after the surrender, knowing they would soon be sold to the West Indies as punishment. Several slaves even drowned in the York River after the campaign ended in a futile attempt to escape recapture. These poignant stories help students better comprehend and remember the events at Yorktown as well as begin to understand the complexities of the Revolution itself (with Americans fighting for liberty on the one hand, while seeking to perpetuate slavery on the other).

Finally, when structuring my classes, I select several different historical narratives on which to focus. No general history course should focus exclusively on one “story-line” at the expense of others. A social historian, for instance, should not ignore critical political events such as the writing of the Declaration of Independence or the ratification of the U.S. Constitution in order to more fully describe the early Republic’s changing social habits and mores. And visa-versa. When I select topics for inclusion, I typically ask myself if this particular narrative contributes to the “whole story” that I want the course to tell. What narratives are absolutely essential to an American history course, such as the adoption of the Declaration of Independence and the U.S. Constitution (and the political and intellectual ideas that led to their writing and implementation)? And what topics are simply important and/or compelling? I usually select a variety of political, military, diplomatic, social, and economic narratives so that students gain as broad a view of the unfolding of U.S. history as possible as well as an understanding of some of the latest trends in American historiography.

Context and History

The three key ingredients for a successful restaurant – so the saying goes – are “location, location, location.” In history, for students to truly understand the meaning of the historical narrative, I tell them they must grasp “context, context, context.” To certain extent, I am being facetious. Post-Modernists have certainly given that word a bad reputation by overcontextualizing many historical issues and events, and hence reducing the past to near-meaninglessness. Nonetheless, students of history need to comprehend that all historical events spin out of a larger constellation of intellectual, social, and cultural forces. Therefore, if the historical narrative is to have weight, substance and depth, students must grapple with context.

The reasons to concentrate on historical context are important and worth exploring. Until the Enlightenment of the seventeenth- and eighteenth-centuries, historians rarely dealt with context in a serious way. The historians of that intellectual movement, for instance, had little patience, empathy, or understanding of the historical actors they wrote about. Locked within their own time and place, scholars such as Gibbon, Hume, and Voltaire brought their own values, assumptions, and preconceptions to their work and writings, and demonstrated little willingness to understand the past on its own terms. Given the bitter religious conflicts of his own age, for example, Voltaire attempted to show the deleterious influence of both religion and religious leaders upon all civilizations of history, from ancient Egypt to the eighteenth century. Priests, popes, and other such leaders, he argued, had acted throughout the centuries out of superstition, greed, and fear, and not because of reason and rationality. In The Idea of History, R. G. Collingwood asserts that, given this animosity toward established religions by Voltaire and other scholars of the era, “the historical outlook of the Enlightenment was not genuinely historical,” but “polemical and ahistorical.” A more recent scholar, Mark Gilderhus, has further pointed out that the Enlightenment historians “failed to carry out the historians’ primary task, that is, to elucidate the past, not merely condemn it.”[3]

Although most eighteenth-century historians shunned context, one scholar of this age did seek to truly understand and interpret the past on its own terms. Giambattista Vico was a relatively unknown Italian philosopher from Naples, who lived from 1668-1744. In 1725, he published a book entitled, The New Science, in which he argued that scholars needed to understand that history is a discipline characterized by ongoing and unstoppable change. Ideas, values, mores, economies, and nations all change from one century to the next. Therefore, to comprehend the actions and motives of peoples and rulers from previous civilizations, historians could not simply treat them like contemporaries; rather, the scholar needed to place them into a “proper perspective” in order to understand their “mental universe.”[4] As a result, Vico studied the languages, myths, legal systems and politics of past societies in order to better grasp their collective deeds and actions. Parts of Vico’s book should certainly be taken with a grain of salt. He implied, for instance, that history is a “science” and that practitioners of the craft simply needed to follow a particular set of rules and axioms in order to discover “the truth.” Hence, he helped to start history down the road to historicism (in the most negative sense of that word), where historical actors are ultimately deprived of freedom and agency, and where history itself is robbed of contingency. Nevertheless, the need for context remains vital for all students of history if they are to accurately and honestly deal with time periods other than the present.

An example of the use of context in my history classes involves Abraham Lincoln. In my course on the American Civil War, Lincoln’s remarkable rise in American politics is closely examined, with the central question being simply “how was Lincoln able to win the highest political office in the land.” To answer this query, students look not just at Lincoln’s background prior to 1860, but at the society in which he grew up. Born on the Kentucky frontier in 1809, Lincoln grew to adulthood ever farther west in the states of Indiana and Illinois. In the early-nineteenth century, people who migrated to these western territories were generally raucous, violent, as well as ambitious for themselves and their families. Most settlers scratched out livings as subsistence farmers, petty rural merchants, and boatmen along the Ohio River. In terms of politics, the people of the West were also incredibly democratic and, indeed, they stood at the vanguard of an American political system that was becoming extraordinarily open to white male adults, regardless of class, education, and breeding. Lincoln rose and eventually prospered in this dynamic social, economic, and political environment.

To convey some sense of this profoundly different world from the one we occupy today, students read excerpts from Alexis de Tocqueville’s Democracy in America[5] and especially Frances Trollope’s Domestic Manners of the Americans. This latter work vividly, humorously, and incisively comments on frontier lifestyles in the West in the 1820s and 1830s. For example, Trollope wrote about American dining habits shortly after her arrival:

“[W]hen the great bell was sounded from an upper window of the house, we proceeded to the dining-room. The table was laid for fifty persons, and was already nearly full. . . . The company consisted of all the shop-keepers (store-keepers as they are called throughout the United States) of the little town. … We were told that since the erection of this hotel, it has been the custom for all the male inhabitants of the town to dine and breakfast there. They ate in perfect silence, and with such astonishing rapidity that their dinner was over literally before our’s was began; the instant they ceased to eat, they darted from the table in the same moody silence which they had preserved since they entered the room, and a second set took their places, who performed their silent parts in the same manner. The only sounds heard were those produced by the knives and forks, with the unceasing chorus of coughing, &c. No women were present except ourselves and the hostess; the good women of Memphis being well content to let their lords partake of Mrs. Anderson’s turkeys and venison, (without their having the trouble of cooking for them), whilst they regale themselves on mash and milk at home.”[6]

Even though the excerpt has nothing to do with Abraham Lincoln, it colorfully illustrates several important aspects about frontier life, including the common practice of communal dining, the lack of refined manners, and the male-dominated culture where women stayed at home while men appeared in public venues. Thus, Trollope’s observations yield significant insights into the larger world that Abraham Lincoln occupied and, thus, they help to put his political rise into “proper perspective.”

Context is also achieved through the skillful and judicious use of images. As we all know, PowerPoint and the Internet provide college instructors today with easy access to thousands of photographs, paintings, and maps. While many academics rightly condemn the overuse of multimedia resources in the classroom (which often reduces education to mere “infotainment”) the correct use of images has a serious pedagogical role, particularly in history. Cultural historian Peter Burke, for instance, notes that classroom images such as contemporary portraits of historical figures “allow us . . . to share the non-verbal experiences or knowledge of past cultures. . . . In short, images allow us to ‘imagine’ the past more vividly.”[7] I use images not so much to transport students to the past, as Henry James does to Ralph Pendrel; rather I employ them in order to lesson the distance between past and present so as to convince students that the past is never truly gone. In fact, we live with the decisions and actions of past historical figures everyday.

I describe below a classroom exercise I have designed using photographs from Lincoln’s second inaugural address; this exercise not only makes the event a three-dimensional occurrence to students, but, more importantly, it conveys to them the impact of Lincoln’s words and ideas on those in attendance and on the American people of 1865. Contemporary images, moreover, are very useful in countering the dazzling visuals that student see on the History Channel and elsewhere where complex issues are often oversimplified, oftentimes via dramatic staged “reenactments;” moreover, television history programming rarely uses contemporary paintings, woodcuts, and artifacts. Thus, if an instructor carefully selects his or her images, PowerPoint presentations can help students see the past more accurately and realistically than otherwise would be the case.[8]

Another means to reduce the distance between past and present, and provide greater context for particular events is to actually take students to historical sites. Many historians, including myself, occasionally lead students on voluntary field trips to such places as Gettysburg, Mount Vernon, and Yorktown. Students typically attend these excursions out of personal interest, but not because of any specific academic assignment. Williams and Mary History Professor James Whittenburg, however, has designed an innovative class called “The Colonial and Revolutionary Tidewater” which merges field trips with the classroom. His course meets on Saturday mornings and afternoons and uses the many historical sites and landscapes surrounding the Colonial Williamsburg-area as teaching tools with which to educate students about seventeenth- and eighteenth-century Virginia. Whittenburg emphasizes that he and his students are “not tourists” during these excursions. Prior to each visit, they all complete a substantial reading assignment related to the site. In preparation for a visit to William Byrd II’s plantation home of Westover, for instance, students read Daniel Blake Smith’s Inside the Great House and a large portion of Rhys Isaacs’s The Transformation of Virginia, 1740-1790.[9] Westover is a magnificent example of mid-eighteenth century planter class’s attempt to physically replicate the social and material culture of Great Britain’s landed aristocracy.

After touring the house, visiting the gardens, and walking the extensive grounds, the class retires to a nearby church-yard and cemetery for lunch and a discussion about the values and customs of the Old Dominion’s elite in the decades prior the American Revolution. The trip – like similar trips to Jamestown, Yorktown, Williamsburg as well as several tidewater archeological sites – helps students visualize and gain context about the past in a way that would be impossible if they remained only in the classroom. Although most higher educational institutions do not have such an abundance of historical sites at their doorsteps, creative instructors can design assignments and/or organize at least one field trip per term to take advantage of the past landscapes that are present in all localities across the nation.[10]

“Thinking Historically” and Engaging with Documents

Nurturing the historical imagination also means equipping students to engage the past directly on their own. This particularly means equipping students to read and analyze primary documents. To prepare students to undertake this task properly a history professor must teach them the proper habits of mind so that they will “think historically.” In other words, students must do more than simply read a text word-for-word for what is says; rather they have to be able to thoroughly analyze a document in order to understand it on multiple levels and to recognize and grasp all of its meanings. This is easier said than done. Stanford University Professor Sam Wineburg wrote an article in The Chronicle of Higher Education in 2003 entitled “Teaching the Mind Good Habits.” In it, he investigates the analytical habits of scholars and students by having them read primary documents in his presence. He found that historians uniformly possessed a unique manner of approaching texts:

Despite the range of documents, periods, and topics represented in my research, nearly all the historians I’ve studied have approached the primary sources that I give them in the same way. They glance momentarily at the first few words at the top of the page, but then their eyes dart to the bottom, zooming in on the document’s provenance: its author, the date and location of its creation, the time and distance separating it from the event it reports, and, if possible, how the document came into their hands. Then the historians mull over that information like a prospector examining a promising rock for ore. Is the document an un-self-conscious diary entry, or a text written to be read by others? Is the author someone noteworthy, or an ordinary person? Did the author write when the events were fresh in his or her mind, or so many years later that memories may no longer be reliable? The answers to questions like those create a framework upon which the historian’s subsequent reading rests.[11]

In follow-up interviews, Wineburg asked these historians about their distinctive approach to reading. They usually shrugged at the question and said, “Why would I mention that? Everyone does it.” Wineburg’s research, however, concludes otherwise. Students who were “[f]resh from high school, where they had been fed a diet of textbook gruel” certainly do not possess such habits of mind. Nor do scholars in other fields. A British literature professor, for instance, gave a dramatic reading to Wineburg of an account of the battles at Lexington and Concord, but she was entirely uninterested in provenance of the piece. In short, she did not ask who the author was, or inquire why he wrote the piece, or question who the audience could possibly be. To teach proper habits of mind to students, therefore, instructors must prepare students to analyze primary documents as fully as possible so that the students themselves will be able to “think historically” and, hence, uncover a source’s deepest and richest meanings.

Primary documents are deployed in history classrooms in many ways. Oftentimes professors will use a single document in the middle of a lecture in order to illustrate or amplify a point. I use Article I, Section 8 of the Constitution, for instance, to illustrate how the delegates at the Philadelphia Convention sought to place limits around the legislative authority of the new national congress. The original source hence confirms the information the instructor conveys. In order to more precisely teach “historical thinking,” teachers also will frequently provide students with multiple primary documents that are linked in some manner. The process of selecting primary sources for student use is a complex one. Instructors must keep in mind various things: are the documents “readable” (meaning will students have the capacity and diligence to work through prose that is sometimes awkward and/or difficult to 21st century readers?)? Do students have the intellectual ability to “decode” the sources for themselves without the professor looking over their shoulders? Will students find the documents compelling or not?

On this latter question, I sometimes use documents dealing with the Salem Witchcraft Trials of 1692. Many students find the Salem episode riveting and many think they know the true story because they have read the play The Crucible in high school. Thus Salem-related documents allow me to introduce a much more complex world into their thinking. As many historians familiar with the Salem outbreak know, colonials in Massachusetts in 1692 were dealing with rapid economic change, ongoing imperial wars between England and France, and threats from hostile Indians to the west and north. They also practiced a form of Protestant Christianity which seems alien and strange to us today. Five or six carefully selected documents relating to the situation in New England in the early 1690s help students grasp these larger contextual issues.

Instructors must also ask themselves when choosing primary sources, what documents in history are essential for students to read and know. While Salem can be a fascinating topic, I also want students in my U.S. history classes (both my survey and upper-level course on the Revolution/Early Republic) to understand the creation and ratification of the Constitution. Using the wonderful website created by Professor Gordon Lloyd and supported by the Ashbrook Center for Public Affairs, I expose students to the Federalist-Anti-Federalist Debates of 1787-88.[12] In a class discussion on the topic, I provide students in advance with five separate documents: there is one essential text – in this case, James Madison’s Federalist #51 – and four other Federalist and Anti-Federalist sources. I have developed a worksheet which students must fill out before class to provide background information on each. Who is the author? What is his background? Why did he write the document? Who is his intended audience? Etc. Only after students understand the document’s provenance and, to some extent, perceive the author’s “mental universe” can they then begin to interrogate and discuss its contents and central meaning(s).

After students gain an understanding of Federalist #51 and discuss its central arguments, we then examine the four other pieces in a similar manner. Most importantly, students must attempt to analyze these latter sources in relationship to Madison’s essay. In other words, how do all these documents all relate to Federalist #51? Do they support Madison’s arguments? How and why do they seek to undercut the positions laid out by the Virginian? More generally, what do these documents collectively tell us about the people and events of 1787-88? What do they add to the narrative of the Constitution’s ratification process?[13] By participating in this exercise, students begin to develop the essential habits of mind needed in order to analyze original texts as thoroughly and incisively as possible. In other words, they start to think like a historian.

As mentioned above, students in one of my classes analyzes photographs, treating them as important primary documents in and of themselves; I also use photographs, however, as tools to help students see major historical events as real and concrete occurrences, three-dimensional episodes that actually took place. In particular, I use rare photographs from the National Archives (and now available online) from Abraham Lincoln’s Second Inaugural Address. I discuss the Second Inaugural speech at length in my upper-level Civil War class in order to convey Lincoln’s (and the nation’s) struggle to understand the momentous conflict and make sense of the horrific bloodshed still going on at the military fronts. The Second Inaugural Address is also immortal for its beautiful (even astounding) conclusion:

“With malice toward none, with charity for all, with firmness in the right as God gives us to see the right, let us strive on to finish the work we are in, to bind up the nation’s wounds, to care for him who shall have borne the battle and for his widow and his orphan, to do all which may achieve and cherish a just and lasting peace among ourselves and with all nations.”

For such sentiments to have been expressed at the conclusion of a bloody civil war – the bitterest of all military conflicts – is remarkable and says much about Lincoln and the American character.

In this exercise, I have students read before class several contemporary accounts of the event, including reports from New York Times correspondents and Frederick Douglass’s recollections of the speech and subsequent meeting with the President at the White House later that day. Students also read Michael Burlingame’s analysis of the Second Inaugural from his magisterial two-volume biography of Lincoln published in 2008.[14] When the class begins, I show students seven illustrations (six photographs by Alexander Gardner and one woodcut illustration from Harper’s Weekly). Organizing them into groups of five students, I ask them to place the photographs in the correct order and, on a worksheet I provide, they need to explain their rationale. Below are the photos in the correct chronological order with my explanations:

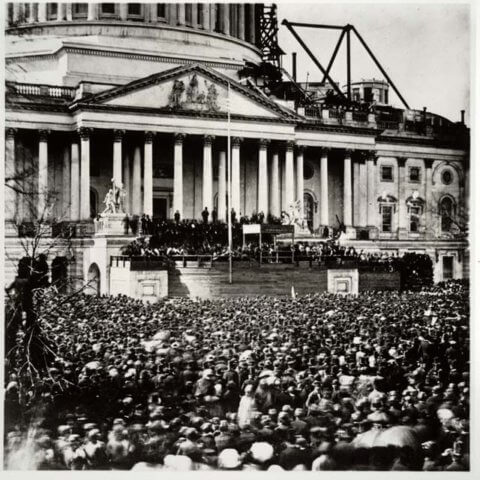

This photo by Alexander Gardner is from the First Inauguration of President Lincoln in 1861. I want students to note the scaffolding around the east front of the Capitol building (the dome was unfinished in 1861, but was completed in 1865). Also, there is a covering over the speaker dais, placed there in order to shield the new president from the sun. This protective structure is not present at the time of the 1865 inauguration ceremonies.

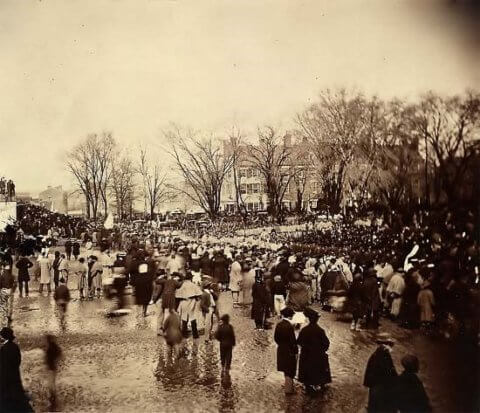

Photograph #2 was taken on the morning of March 4, 1865 as crowds begin to gather before the ceremonies started. The photographer has placed his camera on the East Front of the Capitol Building, but in this shot the camera is facing in a northward direction (toward modern-day Union Station). Press accounts in the New York Times repeatedly made reference to rainy conditions in Washington, D.C. during the morning hours of the 4th. Therefore, I want students to note the umbrella open in the foreground as well as the very wet ground in front of the Capitol (the steps of the building are seen on the extreme left of the photo).

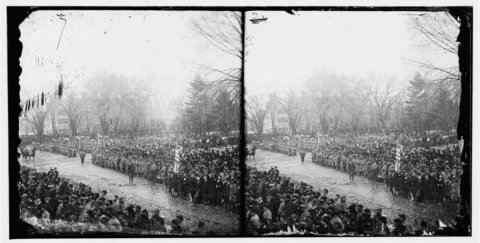

Photograph #3 was taken much closer to the start of the outdoor ceremonies. Crowds are clearly larger, but the inaugural day procession coming from the White House has not yet arrived. But military personnel are ready for the occasion’s start. They stand at attention and officers have cleared the pathway for the arrival of the inaugural party (which ironically did not include President Lincoln. Lincoln had traveled to the Capitol Building unnoticed earlier that morning in order to sign last-minute legislation passed by Congress before the ceremonies began). Speakers may already have begun addressing the crowd, as people in the photograph are clearly looking toward the speaker’s platform.

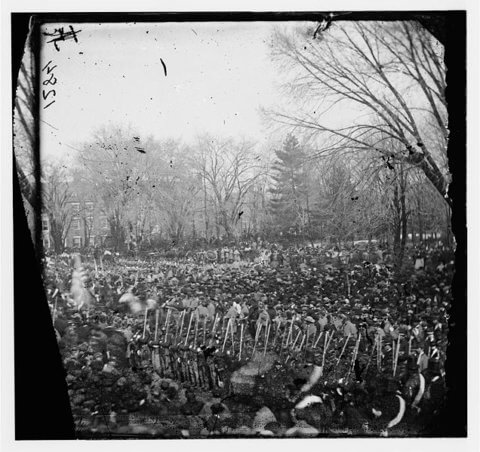

Photograph #4 is at the start of the outdoor ceremonies, marked by the arrival of the Inaugural procession from the Executive Mansion. The sun has also clearly emerged (which the New York Times reporter notes in his account). A column of soldiers is heading down the central aisle (led by an officer on a white horse) and civilian dignitaries are moving from right-to-left in front of a company of African-American soldiers in the foreground. In my discussions with students, I make note of these soldiers who belonged four companies of black troops who took part in the proceedings. Their presence reflected some of the profound transformations bought about by the Civil War – in particular, black emancipation and African-American military service.

Photograph #5 is the most famous taken of this event, quite justifiably because it shows Lincoln actually delivering the address to the assembled crowd. Gardner has turned his camera to the left to show the East Front of the Capitol. The sun continued to shine (Lincoln commented on the change of weather later in the day, remarking that he “was just superstitious enough to consider it a happy omen.”). Most spectators are gazing toward the president as he is reading his address. Michael Burlingame writes that the crowd periodically applauded the speech, but for the most part just listened intently. The exception to this were the African Americans in the crowd – both military and civilian – who collectively and audibly said “bress de Lord” at the end of nearly every sentence.[15]

I believe (but am not sure) that the last photograph (#6) was taken immediately after Lincoln’s speech. Accounts say that following the address, artillery salvos were fired to honor the new administration. The sun continues to shine (which means it likely was not taken earlier). Spectators in the left foreground, moreover, are no longer facing the speaker’s rostrum, and the ranks of the soldiers seem a bit ragged. Hence it seems that they are all about to move off.

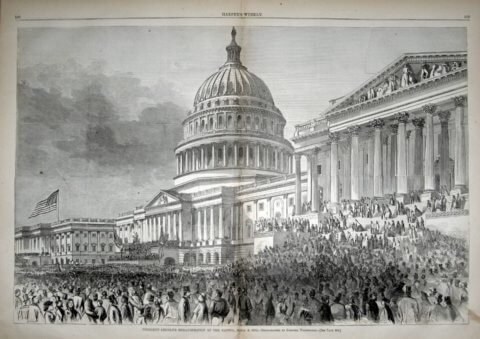

After looking at these photographs, students examine this illustration below from Harper’s Weekly and I ask the students how accurately the print seems to reflect what they have seen in the photographs. The aim to engender a critical attitude when looking at period illustrations and not to view them as equal to photographs.

My interpretation of these photographs is obviously speculative, but the aim is to get the students to see photographs as historical documents and not as simply window-dressing for text. Furthermore, I believe that these photographs, when combined with a substantive discussion of the Second Inaugural itself, help students better see the event through the perspective of the historical actors themselves.

Because a solid understanding of history is so important for all liberally-educated individuals, nurturing the historical imaginations of college students remains a vital and serious task for all history instructors (particularly as students’ civic literacy continues to declines). As this paper demonstrates, there are specific approaches professors can employ to spark their students’ interest as well as tangible strategies to develop their analytical abilities which will allow them to understand and interpret the past on their own. Presenting history in a narrative format certainly is one strategy to help students – particularly novice students – of the discipline. Carefully constructed narrative lectures provide an accessible means for students to begin grasping that history (as a discipline and subject) is accessible and available to them. This fundamental understanding will give them the confidence to probe historical figures and events more deeply and substantively. Context is another essential element of history for students to learn. Indeed, they need to grasp the differences between past and present as they search for the motivations, ideas, and ambitions of historical actors. Without the larger dimension of context, students will too often impose their own opinions and values upon the past and, hence, interpret events in ahistorical terms. Finally, scholar-teachers must design exercises that allow students to analyze and deduce the past for themselves. If they do so, college students will be equipped not only to better understand the past, but they will want to continue learning about history themselves long after they leave college.

Notes

[1] Quotations from The Sense of the Past are from Barbara Taylor, “Introduction: How Far, How Near: Distance and Proximity in the Historical Imagination,” History Workshop Journal, Issue 57 (2004), 117.

[2] Jerome Bruner, “The Narrative Construction of Reality,” Critical Inquiry, Vol. 18, No. 1 (Autumn 1991), 9, 4.

[3] Mark T. Gilderhus, History and Historian: A Historiographical Introduction, Seventh Edition (Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Prentice Hall, 2010), 39.

[4] Giambattista Vico, New Science, Third Edition, translated by David Marsh (New York: Penguin Books, 2000), 106; Gilderhus, History and Historians, 39.

[5] I typically have students read Tocqueville’s chapter 13, which is available at the following site: http://xroads.virginia.edu/~HYPER/DETOC/1_ch13.htm

[6] There are several excellent print versions of Trollope’s book still in print. The full-text is also available at FullBooks.com. The link to Domestic Manners of the Americans is http://www.fullbooks.com/Domestic-Manners-of-the-Americans1.html

[7] P. Burke, Eyewitnessing: The Use of Images as Historical Evidence (Ithaca NY: Cornell University Press, 2001), 13, quoted in Joseph Coohill, “Images and the History Lecture: Teaching the History Channel Generation,” The History Teacher, 39:4(Aug. 2006), 456.

[8] On this entire issue, see Coohill, “Images and the History Lecture,” 455-469.

[9] Daniel Blake Smith, Inside the Great House: Planter Family Life in Eighteenth-Century Chesapeake Society (Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press, 1986) and Rhys Isaac, The Transformation of Virginia, 1740-1790 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1982).

[10] James P. Whittenburg, “Using Historical Landscape to Stimulate Historical Imagination: A Memoir of Climbing outside the Box,” Teaching American History: Essays from the Journal of American History, 2001-2007, edited by Gary J. Kornblith and Carol Lasser (Boston: Bedford/St. Martin’s Press, 2009), 131-139.

[11] Sam Wineburg, “Teaching the Mind Good Habits,” The Chronicle of Higher Education, Vol. 49, Issue 31, 11 April 2003.

[12] The Center’s website on the Constitutional Convention can be found at http://teachingamericanhistory.org/convention/. The URL address for the separate site dealing with the ratification debates and state conventions is http://teachingamericanhistory.org/ratification/.

[13] This exercise (and the student worksheet) is adopted from Frederick D. Drake and Sarah Drake Brown, “A Systematic Approach to Improve Students’ Historical Thinking,” The History Teacher 36:4 (August 2003): 465-489.

[14] Michael Burlingame, Abraham Lincoln: A Life, 2 vols. (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2008).

[15] Burlingame, Abraham Lincoln: A Life, 2: 769.

This excerpt is from The Liberal Arts in America, Lee Trepanier, ed. (Southern Utah University Press, 2012).