The Politics and Experience of Active Love in The Brothers Karamazov

Early reception of The Brothers Karamazov ranged from praise to condemnation, with most of the criticism and debate focused on Book V’s The Tale of the Grand Inquisitor. Both liberal atheists and conservative believers upbraided Dostoevsky for his alleged identification with the Inquisitor’s position against God; while a minority of critics, such as Vladimir Soloviev, applauded Dostoevsky’s exploration and defense of Christianity.[1] In the West interest in The Brothers also focused on The Tale, with commentary ranging from Dostoevsky’s literary techniques to his theories of psychology, philosophy, and theology.[2] Perhaps the most influential of these criticisms both in Russia and the West was M. M. Bakhtin’s Problems of Dostoevsky’s Creative Works that was published in 1929 and later reissued and expanded in 1963 as Problems of Dostoevsky’s Poetics.[3] Crucial to Bakhtin’s criticism was his concept of polyphonism as the interpretative key to understanding Dostoevsky’s works. According to Bakhtin, there exist multiple points of view as represented by the characters in Dostoevsky’s novels, with no one view or position privileged over another: each character possessed a fully valid voice that was either consciously or subconsciously engaged in a dialogue with other characters. Although the author abstained from his authoritative voice in the work, Dostoevsky’s novels nonetheless had a unifying structure in them; or what Bakhtin referred to as a “unity in diversity”: there was an underlying harmony in Dostoevsky’s works in spite of their polyphonic nature.[4]

Unfortunately, this suggestion has been ignored by most commentators on The Brothers; and instead of looking for such a “unity in diversity,” critics have focused on the polyphonic aspect of Bakhtin’s theory to interpret The Brothers. On the one hand, the critics agree that The Tale is the crux to understanding The Brothers; but, on the other hand, they disagree on the significance of The Tale and how it is related to the rest of the book. Some identify Dostoevsky’s position with Christ; others equate his position with the Inquisitor’s; and most, by employing Bakhtin’s polyphonic theory, select one or two characters in the novel for their own philosophical speculation.[5] By adopting Bakhtin’s polyphonic theory, these critics can claim that the author’s beliefs are irrelevant to the interpretation of the novel, because the characters all possess equally valid positions. Within this interpretative context, the critic can adopt a postmodern stance in dismissing the author’s viewpoint and construct any significance to the novel that he wishes.

But not all critics have subscribed to Bakhtin’s polyphonic theory: another group, usually post-revolutionary émigrés and post-Soviet writers, have focused on the religious themes in Dostoevsky’s works.[6] These critics start from the opposite assumption of the Bakhtin camp: the author’s views are relevant to the interpretation of the novel. In spite of occasionally lapsing into a too reverential attitude towards Dostoevsky, these critics acknowledge the attractive power of Book V but contend it is Book VI where Dostoevsky’s own philosophical and theological position are presented. The chief spokespersons for Christianity, Alyosha and Zossima, refute Ivan and the Grand Inquisitor not by logic and reason but rather by indirection and example.

My own interpretation of The Brothers concurs with these critics and builds upon their analyses with a focus on the experiential nature of active love and its role in forging a community of responsibility and memory modeled after the ideals of Christianity. The episodes that best exemplify how active love accomplishes these tasks are found in Zossima’s memoirs, Alyosha’s encounter with Grushenka, and the portrayal of the children in the novel. These episodes represent the “unity in diversity” that Bakhtin had claimed in his study of Dostoevsky’s works. In a sense, I try to reclaim Bakhtin from those who have misused his theoretical concept of polyphony for their own philosophical agenda in the interpretation of the novel: underneath the valid and opposing viewpoints is a unity rooted in Zossima’s teachings of active love and responsibility for all. Thus, contrary to the claim that The Brothers is a polyphonic novel, where the author’s own views are irrelevant to its interpretation, and the claim that Dostoevsky was unable to furnish an adequate defense of Christianity, I contend that the often neglected doctrines of active love and the responsibility for all are the interpretive keys to the novel – Bakhtin’s “unity in diversity” – thereby providing a compelling alternative vision to Ivan’s and the Grand Inquisitor’s.

The Challenge of the Grand Inquisitor

The Tale of Grand Inquisitor begins as a dialogue between the two brothers, Ivan and Alyosha, where the former acknowledges his incapacity to experience Christian love for one’s fellow neighbors. “I could never understand,” Ivan says, “how one could love one’s neighbors . . . though one might love them at a distance.”[7] Ivan can only see the possibility of Christian love as a Kantian categorical imperative: something required or imposed upon by duty. The cruelties of humans, especially on innocent and helpless children, had led Ivan to conclude that humans are nothing more than monsters of destruction. Adopting a rationality of cause-and-effect, “Euclidean reason,” Ivan finds the suffering of the innocent intellectually incomprehensible and emotionally unendurable, for “The innocent must not suffer for another’s sins, and especially such innocent [children]!” (14:215). He rejects the idea of a higher and universal harmony, such as a Christian Paradise where all is forgiven and reconciled: “I don’t want harmony. From love of humanity, I don’t want it. I would rather be left with unavenged suffering . . . even if I were wrong” (14:223). The depth of Ivan’s rejection is so great that he declares, “And so I hasten to give back my admission ticket, and if I am an honest man I must give it back as soon as possible . . . . It’s not God that I don’t accept, Alyosha, only I most respectfully return Him my ticket” (14:223).[8]

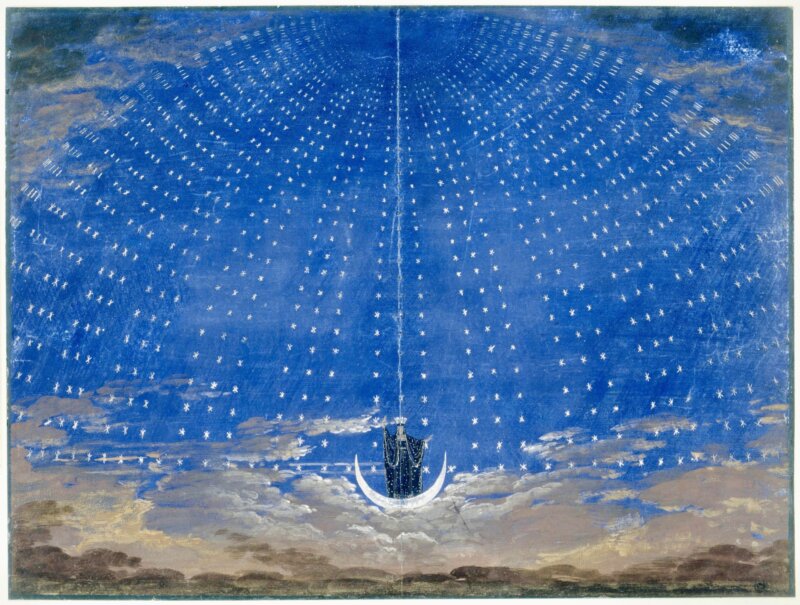

This sense of outrage against God is dramatically portrayed in Ivan’s unfinished poem, The Tale of the Grand Inquisitor. In The Tale Christ returns to Seville during the darkest days of the Inquisition, where “everyone recognized Him . . . He moves silently in the people’s midst with a gentle smile of infinite compassion. The sun of love burns in His heart. Light, Enlightenment, and Power shine from His eyes, and their radiance, shed on the people, stirs their heart with responsive love” (14:226). While Christ performs His miracles, prompted by the “responsive love” between Him and the people, the Grand Inquisitor, “an old man, almost ninety, tall and erect with a withered face and sunken eyes,” orders the arrest of Christ and throws Him into prison where the two confront each other face-to-face. While Christ remains silent, the Grand Inquisitor asks why Christ had return “with empty hands, with some promise of freedom,” when He could have accepted the first temptation in the desert of turning stones into bread. If He had done so, “mankind will run after Thee like a flock, grateful and obedient”; instead, Christ refused because it would deprive “man of freedom . . . thinking, what is freedom worth if obedience is brought with bread?” (14:230). Christ’s refusal therefore is a refusal to command human conscience – a refusal that is reinforced by Christ’s rejection of the second and third temptations: proof His own divinity and acceptance of temporal power to enforce His faith on earth.

By refusing to “take possession of man’s freedom,” the Inquisitor charges Christ, “You have increase man’s freedom and burdened his spiritual kingdom with suffering forever . . . In place of the rigid ancient law, man now must with a free heart decide for himself what is good and what is evil, having only Your image before him as a guide” (14:232). But because humans are “weak, vicious, worthless, and rebellious,” incapable of acting out of the self-sacrifice that Christ had demanded, His message will fail. In its place the Grand Inquisitor has taken upon himself the burden of freedom to provide meaning to humans under the guise of Christ’s name: “We corrected Your work and [instead of freedom of conscience] have founded it upon miracle, mystery, and authority.” (14:234). Initially humans will attempt to discover the meaning of existence for themselves – whether in science, reason, or waiting for the return of Christ – but eventually they will grow weary and look upon the Inquisitor to provide them a universal happiness: “we shall persuade them that they will become free only when they renounce their freedom to us and submit to us,” and humankind will be reduced to the level of children,” with every detail of their lives under the Inquisitor’s control. “Peacefully they will die, peacefully they will expire in Your name, but beyond the grave they will find nothing but death,” for immortality does not exist (14:235-236).

Although the Grand Inquisitor’s secret is that he works for the Devil and not for Christ – “We are not with You but with him – that is our mystery” – he is not an atheist who has joined the forces of Enlightenment and reason (14:234). For Ivan, the Grand Inquisitor is a tragic figure who genuinely suffers, because he “has wasted his whole life in the desert and yet could not shake off his incurable love for humanity”; and this suffering only increases because he “leads men consciously to death and destruction and yet deceive them all the way . . . in the name of Him in whose ideal the old man had so fervently believed all his life long” (14:237-239). Perhaps recognizing his suffering, Christ responses to the Inquisitor’s monologue with a kiss on the lips, prompting the Inquisitor to shudder and open the cell door for Christ. “Go,” he commands Him, “and come no more – come not at all, never, never.” After Christ has left, “the kiss glows” in his heart, but the old man sticks to his idea” (14:240).

By itself, the Tale provides a compelling argument against Christianity; but in the context of the entire novel, it is one of a series of lacerations (nadryv) that various characters exhibit, which only active love can heal. Throughout The Brothers, particularly in the characters Dmitry and Feodor, the reader is reminded of the “Karamazov baseness” – the earthly drive for sensuality – to which Ivan himself admits of possessing, “It is a feature of the Karamzavos, it’s true that the thirst for life regardless of everything, you have it no doubt too, but why is it base?” (14:209). This baseness can be channeled into an indulgence of gross sensuality, as demonstrated by Feodor’s and Dmitry’s exploits, but it also can be transformed into a life-sustaining force, as Ivan acknowledges:

“. . . even if I didn’t’ believe in life, if I lost faith in the order of things, were convinced in fact that everything is disorderly, damnable, and perhaps devil-ridden chaos, if I were struck by every horror of man’s disillusionment – still I would want to live, and having once tasted of the cup, I would not turn away from it until I have drained it . . . . I have a longing for life, and I go on living in spite of logic” (14:209).

The attempt to rise above this “Karamazov baseness” is usually to deny one’s material, sensual nature, resulting in a fragmentation or laceration of oneself. The assumption of higher motives for one’s actions – honor, nobility, love – at the expense of our material nature is to both objectify ourselves and others that in turn create a condition of incoherence and self-fragmentation. An example of this is Katrina’s alleged love and devotion to Dmitry. Disgraced earlier by Dmitry, Katrina’s profession of love is really a form of vengeance or baseness, although she refuses to admit it and causes harm both to herself and others exposed to her.

Ivan also engages in a type of laceration with his Euclidean compassion and concern for humankind – a “laceration of falsity,” as Alyosha suspects (14:215-216). Ivan’s claim of love and compassion for humankind disguises his “Karamazov baseness” – his love of nature’s “sticky little leaves as they open in spring” – and has transformed itself into a life-sustaining force that compels him to search for a meaning of existence. Of course, Ivan’s intellect and logic had led him to conclude that life is meaningless, with his declaration of committing suicide when he turns thirty, because he is torn between his reason and “baseness.” This conflict causes Ivan’s laceration of falsity with his claims of love and compassion for humankind instead of acknowledging his own base need for companionship and love – something which the author implicitly suggested in the beginning of Book V when he pointed out that Ivan has no friends. Ivan’s rebellion therefore is nothing more than a laceration of himself in the denial of his need of companionship and love – a theme that surfaces throughout the novel in such characters like Grushenka, Alysoha, and Kolya.

Given this understanding of Ivan’s laceration, The Tale is not a conflict between faith and reason, Christianity and Enlightenment, or Christ and the Anti-Christ; rather it is a dramatic account of Christianity in its lacerated form.[9] The Grand Inquisitor’s project is a fusion of both strands of Western Christianity: the Catholic provision of happiness to all people with a Protestant elect shouldering the burden of freedom. Ivan sees the choices that Christianity can offer as either the Catholic realization of happiness in a totalitarian state or the Protestant responsibility of individual freedom that eventually collapses into a Hobbesian state of war of all against all. The only possible solution to this problem is the Grand Inquisitor’s project of claiming Christian love but ruling as a totalitarian state. Thus, the conflict between the universal happiness of Roman Catholicism and the individual freedom of Protestantism ultimately become reconcile in the Grand Inquisitor’s solution.

But Ivan’s presentation of Christianity is de-contextualized from the Christian community: individual freedom does not occur in a vacuum but within a community that cultivates and supports people to make the right choices from their consciences. Furthermore, Ivan’s presentation of Christianity is incomplete, with Orthodox Christianity absent except for Christ’s (and Alyosha’s) kiss, representing the mystical and experiential nature of Christianity. By presenting a de-contextualized Chrsitianity, Ivan is able to offer to the reader a false dichotomy of two lacerated versions of Christianity; but, it will be in Book VI, with its examination of Orthodox Christianity, that will re-contextualize the aspirations of Christianity in its unlacerated form and provide a response to the Tale. Dostoevsky himself wrote about this account of Christianity in its Catholic, Protestant, and Orthodox forms:

“On one side, at the edge of Europe, there is the Catholic idea – condemned and waiting in great torment and perplexity: Is it to be or not to be? Is it still to live or has its end come? . . . In that sense, for instance, France over the ages has seemed to be the most complete incarnation of the Catholic idea . . . This France, who developed from the ideas of 1789 her own particular French socialism – i.e., the pacification and organization of human society without Christ and outside of Christ . . . is and continues to be in the highest degree a Catholic nation wholly and entirely, completely contaminated by the spirit and the letter of Catholicism. . . . For French socialism is nothing other than the compulsory union of humanity, an idea that derived from ancient Rome and that was subsequently preserved completely in Catholicism . . . On the other side rises up old Protestantism. . . .This is the German . . . Through his entire history he dreamed only of and longed only for his unification so he could proclaim his own proud idea . . . And meanwhile, in the East, the third world idea – the Slavic idea, a new idea that is coming into being – has truly caught ablaze and has begun to cast a light that has never before been seen; it is, perhaps, the third future possibility for settling the destinies of Europe and of humanity” (25:6-9).

From his entries in Diary of a Writer, personal correspondences, and private writings, we know that Dostoevsky believed that Orthodox Christianity was the remedy and answer to an Enlightened Europe and Western Christendom. Contrary to Bakhtin’s followers, Dostoevsky did not envision The Brothers as a polyphonic piece without a unifying structure or had subconsciously sided with the Grand Inquisitor, although he acknowledged his anxiety if he were to fail in his vindication of Orthodox Christianity.[10] As he wrote:

“As an answer to all this negative side, I am offering this sixth book, ‘A Russian Monk.’ . . . And I tremble for it in this sense: will it be a sufficient answer? All the more so because the answer here is not a direct one, it is not a point-by-point response to any previously expressed positions (in the Grand Inquisitor or earlier) but only an oblique response . . . so to speak, in an artistic pictures” (IV: 209).

The Response of the Russian Monk

For Zossima, the modern predicament for humankind is radical individualism where people are isolated and alienated from one another. This isolation, alienation, and radical individualism are a product of laceration, where humans reject God and therefore deny their proper place in the world, with their pride and egoism dictating their “Karamazov baseness” toward continual sensual and material pleasure. The cure for this modern condition is kenosis: the negation of selfhood where we feel a responsibility for everyone and everything, thereby prompting us to engage in active love to improve our individual and communal condition. These two doctrines – responsibility for all and active love – are presented in Book VI, The Russian Monk, as an indirect refutation against The Tale. The actual content of the Book is the Elder Zossima’s memoirs and sermons, with the former divided into three narratives: 1) the death of Zossima’s older brother, Markel; 2) the early life of Zossima whose abuse of a servant leads him to change his life; and 3) Zossima’s encounter with a mysterious stranger who, after conversations with Zossima, declares his guilt as a murder.

In the first narrative, Markel is portrayed as an atheist freethinker, but upon succumbing to a terminal illness, “a marvelous change passed over him, his spirit was transformed” (14: 261). By accepting his own death, Markel was awaken to the value of life to the point of desiring to trade places with his servants and begging for forgiveness from nature because he “did not notice the beauty and glory” of it (14:263). Markel’s experience of the value and beauty of life is similar to Ivan’s love of life, even if it against “logic,” and what Zossima passes down to Alyosha. The rest of this narrative recounts Zossima’s reading of the Book of Job as “a mystery – that the passing earthly scene and the eternal verity are brought together in it” for, “it’s the great mystery of human life that old grief gradually passes into tender joy”; and urges priests to spread the Gospel among the people rather than performing their assigned clerical duties (14:265).

The second narrative describes Zossima’s vicious, debased behavior after military cadet school in St. Petersburg (14:268). He forms an attachment with a respectable, young lady but delays marriage for two-months in order to continue his debaucheries. When he returns, Zossima discovers she is already married to someone else and that she had been engaged to this suitor while Zossima was courting her. Furious, Zossima challenges the husband to a duel and strikes his orderly, Afanasy; but, on the morning of the duel, he regrets his challenge, with the beauty of nature filling him with shame – the lesson of Markel has reawaken in Zossima’s soul – and leads him to ask for forgiveness from Afanasy (14:270). At the duel Zossima allows the husband the first shot, which misses, and refuses to fire in return, asking for forgiveness for his insult. Zossima’s refusal to return fire causes a scandal in his regiment and he resigns his commission, announcing that he will enter the monastery.

The final narrative is about the visits of a respected, philanthropic, family man to the young officer Zossima, who now has earned a reputation for following his own conscience rather than the expectations of society. The mysterious visitor is interested in what had motivated Zossima to follow his own conscience, because he has “a secret motive of my own, which I may perhaps explain to you later on” (14:274). His secret is that, when he was young, he had murdered a girl who had refused his suit and managed to escape prosecution. The visitor had hoped that his philanthropic activities and later his marriage and family would erase the memory of his crime; but, he has become more haunted by it. He agrees with Zossima’s assertion that “all men are responsible to all for all, apart from our sins . . . the Kingdom of Heaven will be for them not a dream but a reality”; but wonders whether such a condition is possible, given the nature of modern society, where everyone is isolated and alienated from one another (14:275). Zossima replies that it is possible but it is a long spiritual and psychological process: “Until you have become really, in actual fact, a brother to everyone, brotherhood will not come to pass. No sort of scientific teaching, no kind of common interest, will ever teach us to share property and privileges with equal consideration for all” (14:275). The visitor eventually accepts Zossima’s advice and makes a public declaration of his crime, even furnishing evidence to support it. Nobody believes this exemplary citizen and instead of prosecuting him they have him declared insane, where he ultimately is taken ill and dies.

Zossima concludes with a sermon about two ways of life: the material world with its pursuit of pleasure and desire, and the ecclesiastical world with its obedience, fasting, and prayer. The fundamental difference between these two worlds is their conception of freedom: freedom in the material world is the unbridled pursuit of one’s desires; freedom in the ecclesiastical world is to restrain and control these desires. To counteract this material understanding of freedom, Zossima urges Orthodox monks to spread the Gospel and to save the Russian people from the ailments of modernity. They should strive to emulate Christian ideals, in particular they should continue to pray and practice active love, for it is necessary “to love a man even in his sin, for that is the semblance of the Divine love and is the highest love on earth . . . [and] all of God’s creation, the whole and every grain of sand in it. Love every leaf, every ray of God’s light, love the animals, love the plants, love everything” (14:288-289). Children are especially singled out by Zossima for love, “for they are sinless like the angels, they live to soften and purify our hearts and as it were to guide us.”

Zossima’s exhortations reside on the mystery, beauty, and value of all life; and Christ was sent down to remind humans of God’s love for all of life: “God took seeds from different worlds and sowed them on the earth, and His garden grew and everything came up that could come up, but what grows lives and is alive only through the feeling of its contact with other mysterious worlds. Once contact is lost, then you will be indifferent to life and even grow to hate it” (14:290-291). This need for human contact can be fulfilled by active love, as Zossima speculates on the creation of humanity: “Once, only once, there was given him a moment on his coming to earth, the power of saying: ‘I am and I love . . . Once, only once, there was given him a moment of active living love, and for that earthly life was given him” (14:292). Active love therefore is part of human nature which individuals should embrace and practice in order to counteract the rationalism, secularism, and materialist understanding of freedom in the modern world.

Dostoevsky dramatically portrays how active love, and its accompanying doctrine, the responsibility for all, actually work in Book VI, where Markel teaches his younger brother to love and value life, a lesson that is in turn Zossima passes down to Alyosha. The transmission of active love is not doctrinal in the sense of memorizing a set of teachings or logical procedures; rather, it is experiential in nature that passes mysteriously from one person to another. As Zossima had told Madame Khokhlakova that such subjects like the immortality of the soul cannot be proved, but “one can be convinced by the experience of active love” (14:52).[11] Of course, appeals to the experiential nature of active love automatically will be rejected to those who rely upon reason; but it may be the only possible avenue available for Dostoevsky given the limitations of language. As best, language can only point to or indicate human experience; it cannot fully capture it and transmit it like a data set to another person – a view that Dostoevsky himself held about the inherent inability of language to reveal the deepest truths of human existence (29:2).[12]

By appealing to experience, Zossima’s doctrine of active love reintegrates isolated individuals back into a community where the aspirations of Christianity become re-contextualized. Whereas Ivan had presented Christianity as either happiness for all or individual freedom, Zossima furnishes an account of Christianity that emphasizes both happiness and individual freedom within a community. Within the context of a community, the aspirations of Christianity are possible: people possess freedom to make choices for their individual and for the community’s happiness. This condition only is possible with Zossima’s understanding of freedom not the pursuit of pleasure but the restraint on human desires for the individual and communal good. Ivan’s understanding of freedom is ultimately self-defeating: the pleasure principle leads to conflict among individuals over limited resources, resulting in the Inquisitor’s totalitarian state as the only viable political solution.[13] By contrast, Zossima’s definition of freedom provides an escape from the cycle of satisfaction and emptiness that accompanies those who follow the pleasure principle: genuine happiness is the acceptance of life, including all its pain and suffering, for “It’s a great mystery of human life that old grief passes gradually into quiet tender joy” (14:265).

Although Zossima’s acceptance of the mystery of existence may strike some as hopelessly naïve, it is epistemologically consistent with the Christian account of human nature. The possession of reason is a great advantage for humans to navigate themselves in the world, but it cannot stand outside of realm of reality, since humans are bounded spatially and temporality. The tragedy of Ivan is that he wishes to transform Euclidean reason from a finite viewpoint to a vantage point outside of space and time – an impossible feat. In fact, the attempt to make reason survey all of reality – and therefore transform it according to the person’s will – is reflective of the individual who is isolated from his community. Thus, the presentation of a de-contextualized Christianity reflects Ivan’s own experience in the novel, as a young, intellectually-gifted man with no friends – no community – to which he can reach out for mutual support. But when someone exists within a community, with all their demands, obligations, and requests, the person is aware of the limited cognition of his own situation and therefore is more receptive to the mystery of reality.

Finally, Zossima’s rebuttal of Ivan’s position is not only epistemological but social and political with his doctrine of responsibility for all, where “the moment you make yourself responsible in all sincerely for everyone in all sincerely for everyone and everything, you will see at once that it really is so and that you are, in fact, responsible for everyone and everything” (14:291). The experiential sense of interconnectedness with others propels us to not only accept that we are complicit in the suffering that exists in the world but that we are obligated to improve things through active love. Zossima’s continual emphasis on active love suggests that acceptance of the mystery of existence does not equate into social and political passivity; rather, it implies the opposite. When people engage in active love, they will experientially expose others to Zossima’s vision of epistemological humility, self-constrained freedom, and a socially-bound community where the ideals of Christianity become contextualized and consequently can become possible.

The Experience of Active Love

Dostoevsky continued his indirect response to The Tale in the dramatic actions of the character Alyosha and his engagement with the children. Earlier, Alyosha had urged Ivan to love life “regardless of logic as you say, it must be regardless of logic, and it’s only then one can understand the meaning of it” (14:209-210). The model for discovering the meaning of life is Christ, who has forgiven “everything, all and for all, because He gave His innocent blood for all and everything. You have forgotten Him, and on Him is built the edifice, and it is to Him they cry aloud, ‘Thou art just, O Lord, for Thy ways are revealed!’” (14:223-224). Because Christ has sacrifice himself for all of humanity, everyone becomes indebted to Him and thereby are responsible to everyone else and to everything. The foundation for the regime is not based on the innocent blood of victim, as Ivan had proposed; rather, the regime is rooted in the self-sacrifice of Christ that allows humans to accept the happiness and suffering of everyone in the Christian community. The doctrine of the responsibility for all is prompted by the action of active love – which is why Zossima instructs Alyosha to leave the monastery in order to marry Liza Khokhlakova and to prevent parricide in his family. Alyosha obeys and departs from the monastery but only possesses a lacerated understanding of Zossima’s teaching: a doctrinal and dogmatic knowledge instead of experiential and mystical one.

Alyosha tries to follow the Christian ideals of sacrifice, responsibility, and love by preventing Dmitry from killing their father in Book III and later, imitating Christ in The Tale, kisses Ivan when they leave in Book V; however, the experiential nature of Zossima’s teachings do not attach themselves onto Alsyhoa’s soul until he practices active love with Grushenka in Book VI. Depressed over the death and disgrace over Father Zossima’s death – people expected the body to remain odorless because Zossima was such a holy man; and when the body began to sink, people saw it as a sign God’s disapproval – Alyosha asked why had God disgraced “the holiest of holy men . . . as though involuntarily submitting to the blind, dumb, pitiless laws of nature” (14:306). Like Ivan, Alyosha looked for a higher justice that would reconcile the laws of nature with the goodness of God. When this higher justice failed to appear, Alyosha became distraught to the extent that he allowed the career seminarian Rakitin to arrange a visit to Grushenka, who wishes to seduce him.

The ease which Alyosha loses his faith in the Christian ideals of sacrifice, responsibility, and love can be attributed to the fact that “All the love that lay concealed in his pure young heart for ‘everyone and everything’ had, for the past year, been concentrated – and perhaps wrongly so – primarily on his beloved elder, now dead” (14:306). This is Alyosha’s own laceration: although Alyosha recognizes the teaching of the responsibility for all, he lacks the experiential understanding of this truth due to his youth and his misattribution of the doctrine to Zossima. This misattribution is not surprising, given the nature of the institution of the Elders, where novices who have voluntarily submit themselves to an elder commit their will entirely to his guidance in “the hope of self-conquest, of self-mastery” (14:28). Alyosha submitted himself to Zossima in this way and misinterpreted the latter’s teaching to Zossima instead of to everyone and everything. When Alyosha had accepted the devil’s second temptation of miracles, he became disillusioned with Zossima and his teaching, correcting Rakitin that “I am not rebelling against my God; I simply ‘don’t accept his world’” (14:308).

But when Alyosha arrives at Grushenka’s home, the planned seduction goes awry after she hears of Zossima’s death and reacts with genuine sorrow. Alyosha in turn is moved – “and a light seemed to dawn in his face” – by Grushenka’s pity, telling Rakitin that “I’ve found a true sister, I have found a treasure – a loving heart. She had pity on me just now . . . I’m talking about you, Grushenka. You’ve just restored my soul” (14:318). This prompts Grushenka to express remorse over her intention to seduce Alyosha, as she had done with his father and brother, Dmitry, and how this experience has transformed her life, triggering her childhood memory of a folktale she heard from a peasant she still employs. The tale is about a wicked old woman who was in the fiery lake of Hell. Her guardian angel wondered what good deed she had done in order to tell God; and he remembered that she had once given an onion to a beggar. God replied to “take that onion and hold it out to her in the lake, let her catch hold of it and pull it, and if you can pull her out of the lake, let her come to Paradise, but if the onion breaks, then the woman must stay where she is” (14:319). The angel lowers the onion to pull her up, but when the other sinners cling to her as she rises, she began kicking them, crying out “It’s me who’s being pulled out and not you.” At that moment, the onion broke, with the woman falling back into the lake and the angel departing.

This “onion” tale is not only a condemnation of self-centered egoism and radical individualism but a correction to the Tale. Both egoism and individualism precludes a sense of community, thereby making it impossible to be responsible for anyone besides oneself. In the context of self-centered interest, people are seen as competitors over limited resources instead of participants in a common enterprise; and stability only can be restored through a totalitarian regime. The wicked old woman’s willingness to remain in Hell with her comrades rather than allow a few them of them join her in Paradise is the more accurate portrayal of the Grand Inquisitor’s regime than an elect who sacrifice themselves for the many. The purported nobleness and sacrifice of the Grand Inquisitor is exposed by the wicked old woman’s self-centered egoism: it is acceptable if she were to enter Paradise because of her one act of charity; but it is not acceptable for others, who have done nothing of the sort, to enter Paradise with her, because it violates the cause-and-effect of Euclidean reason. By contrast, in taking responsibility for everyone and everything, the cause-and-effect of Euclidean reason becomes inconsequential, for someone like Zossima who accepts the mystery of existence with the belief that eternal life, as assigned by God, will be the true, higher justice.

This vision of a higher justice is experienced by Alyosha when he returns to the cell where Father Paissy holds vigil besides Zossima’s corpse. Alyosha begins to pray with “a sweetness in his heart . . . and joy, joy was glowing in his mind and in his heart” (14:325). This sweetness and joy in his heart is the experiential understanding of the responsibility for all as prompted by his encounter of active love with Grushenka. It becomes further cemented with his dream of the wedding feast in the “Cana of Galilee,” where Christ performs his first miracle by transforming water into wine. Alyosha sees Zossima in the dream who explains his presence by saying, “I gave an onion to a beggar. And many here have given only an onion each – only one little onion . . .” (14:325-327). Zossima urges Alyosha to continue his work and look at Christ who is a guest at the wedding feast, “He is terrible in His greatness, awful in His sublimity, but infinitely merciful”; He “had made Himself like unto us from love and rejoices with us.” Alyosha awakens with “tears of rapture” in his soul and walks out into the night where he experiences religious awe:

The silence of the earth seemed to merge into the silence of the heavens, the mystery of the earth came in contact with the mystery of the stars . . . Alyosha stood, gazed, and suddenly he threw himself down upon the earth. He could not have explained to himself why he longed so irresistibly to kiss it, to kiss it all, but he kissed it weeping, sobbing and drenching it with his tears, and vowed frenziedly to love it, to love it forever and ever . . . It was a though the threads from all those innumerable worlds of God met all at once in his soul, and it was trembling all over ‘as it came in contact with other worlds.’ He wanted to forgive everyone and for everything, and to beg forgiveness – not for himself, but for all men, for all and for everything” (14:328).

“When Alyosha rose from the earth, he was ‘a weak youth’ but now ‘a resolute fighter for the rest of his life,’ and never forgot that moment in his life: “’Someone visited my soul at that hour!’ he used to say afterwards with firm faith in his words . . .”

Dostoevsky’s ambiguous and vague description of Alyosha’s experience is perfectly suitable, since, as stated previously, language is unable to convey experience with complete accuracy from one human being to another.[14] This is why Dostoevsky must response to The Tale indirectly, because the response rests on an experiential foundation that to which at best can be pointed or indicated. A set of syllogism to prove something like the responsibility for all would not convince the reader that The Tale was the inferior argument because such a presentation at the outset epistemologically favors reason over experience. The adoption of a dramatic interplay between characters is a better strategy by showing how characters experience for themselves the doctrine of responsibility of all through active love. From Alyosha’s encounter with Grushenka, the reader sees that Christ’s demand upon humans is not impossible, as the Inquisitor had claimed: both Alyosha and Grushenka reveal the depth of unselfish love and how it restores lacerated people. Christ’s demands of humans are shown to be perfectly just; and, as the “Cana of Galilee” illustrates, He inspires his followers to give their own “little opinion” to their fellow humans. This vision prompts Alyosha to embrace the earth and the stars, for his “Karamazov baseness” has been transformed and healed himself. By accepting both the material and spiritual aspect of his nature, Alyosha is able to restore his fragmented self, as initiated by the sinner Grushenka’s pity for him, and he can go forth to heal other lacerated people in the community.

The Politics of Love and Memory

Alyosha’s attempt to heal lacerated people is dramatically portrayed throughout the novel, but it is probably best illustrated in his engagement with the children who represent the new generation in Russia with Alyosha eventually becoming their spiritual guide. Of particular importance is the relationship between Alyosha and Kolya who is the intellectually-advanced and the future leader of the group of boys. Kolya is resistant to emotional displays and “read some things unsuitable for his age” from his father’s library (14:463). He reveals his precociousness to Alyosha by telling him that “God is only a hypothesis” and that “it’s possible for one who doesn’t believe in God to love mankind”; and he repeats what Rakitin, who has become a rival to Alyosha in the education of the boys, has taught him: “I am not opposed to Christ . . . He was the most humane person, and if He were alive today, He would be found in the ranks of the revolutionaries, and would perhaps play a conspicuous part” (14:499-500).

Given these views, albeit second-handed, Kolya has engaged in a series of escapades that exhibited his intellectual ability and emotional control: lying between railroad tracks while a train passes over him, persuading the slow and stupid to destroy other people’s property, and refusing to visit his ailing friend, Ilyusha. Although the other boys have visited Ilyusha and have searched for his dog, Zhuchka, to relieve Ilyusha’s guilt for putting a pin into a piece of bread for dogs to eat, Kolya has refused to visit because he wish to demonstrate his independence from Alyosha’s influence and that he himself has founded Zhuchka, teaching the dog to do tricks, and wanted to complete its training. But Kolya is not evil but rather immature, as to be expected from children, for if he “had known what a disastrous and fatal effect” of hiding Zhuhka from Ilyusha “might have on the sick child’s health, nothing would have induced him to play such a trick on him” (14:491). In fact, when Kolya finally visits his dying comrade, “his voice failed him . . . his face suddenly twitched and the corners of his mouth quivered” (14:488). His composure of emotional restrain and rationalism gives ways to feelings of empathy and compassion.

Kolya’s laceration is similar to Ivan’s, except that his views are acquired rather than self-created and that he is still young enough to change, which eventually happens to him under Alyosha’s influence. Alyosha’s growing influence over Kolya is representative of the work that Zossima commanded Alyosha to do in the world outside the monastery, as Kolya learns from Alyosha that his pride has misguided him in the treatment of Ilyusha. He first listens to Kolya’s second-hand opinions about God, socialism, and other revolutionary ideologies, responding “quietly, gently, and quite naturally, as though he were talking to someone of his own age, or even older” (14:500). The need of children to be taken seriously by adults is a powerful one that can propel intellectually-gifted children like Kolya into revolutionary ideologies when their ideas are dogmatically dismissed from their religious elders. A better strategy is to engage with children as their equals in the hope that they will expose their insecurities. Kolya does exactly this, confessing that “I am profoundly unhappy, I sometime fancy all sorts of things, that everyone is laughing at me, the whole world, and that I feel ready to overturn the whole order of things” (14:503). He admits that it was his vanity and pride that precluded him from visiting Ilyusha, to which Alyosha asks him to overcome his faults and fear of failures by visiting his friend. The scene concludes with Kolya, Ilyusha, and the captain embracing one another as a community united by suffering, pathos, and the Christian hope of eternity.

The funeral of Ilyusha is the final scene in the novel, with the family distraught over their little boy’s death. When the group of boys pass the stones under which Ilyusha had wished to be buried, Alyosha calls the boys together and asks them to make a pact to never forget Ilyusha or one another, cherishing the memory of Ilyusha and “how good it was once here when we were all together united by a good and kind feeling” (15:195). Alyosha then proclaims that “there is nothing higher and stronger and more wholesome and good for life in the future than some good memory, especially memory of childhood and home.” The boys promise to remember and shout out “Karamazov, we love you,” to which Alyosha adds, “And may the dear boy’s memory live eternally!” The reference to eternity prompts Kolya to inquire whether that bodily resurrection is true and whether they “shall live and see each other again, all, Ilyushechka too?” Alyosha replies in the affirmative that it shall be so, and “hand in hand” they all go to the funeral dinner to eat pancakes, for “it’s a very old custom.”

The death of Ilyusha is remembered as a community of friendship based on the Christian hope of the bodily resurrection instead of the tragic death of an innocent child – another indirect response to the Tale. This transformation of memory connects the new community of believers and cements their bonds of friendship.[15] The slow conversion of Kolya from his atheist socialism to his tepid acceptance of Christianity was the result of Alyosha’s active love, revealing how active love can experientially transform lacerated individuals into a community of friendship, hope, and memory. This experience has been demonstrated dramatically from Markel to Zossima to Alyosha to Kolya and, finally, to the reader himself. Again, this appeal is indirect because of the inherent limitations within language, but Dostoevsky more than meets the challenge of the Inquisitor. Dostoevsky can lead the reader to the experience of active love in illustrating how it operates, although ultimately it is up to the reader to see whether such an experience exists within him.

Conclusion

Dostoevsky’s indirect appeal to the reader is best demonstrated when one discovers that the arguments of both the Inquisitor and Zossima in Books V and VI are structurally and logically identical, as Cassedy demonstrates.[16] For example, the argument of the Inquisitor is as follows: justice does not exist in the world because it is not perceptible to our senses, with the proof being that events fail to correspond to our conception of God’s justice. The assumption to the Inquisitor’s position is that reality does not exist outside of our senses (or either God is fundamentally unjust or not omnipotent), which leads us to the conclusion that justice does not exist either in this world of the next. When we examine Zossima’s argument in Book VI, we see the structure and logic of the argument are the same to the Inquisitor’s: justice exists in the world but it is imperceptible to us, with the proof being that, even if events do not correspond to our conception of God’s justice, we accept this condition because God is not accessible to our senses. The assumption is a reality does exist outside the realm of our senses (and that God is just and omnipotent), which leads us to conclude that justice exist in both this world and the next. The only way the reader can decide between these two positions is based on his own subjective belief in God: on the one hand, if he lacks a belief in God, then he will agree with Inquisitor; on the other hand, if he believes in a God, then he will accept Zossima’s teachings. Since the arguments are structurally and logically identical, reason cannot decide which argument is superior. Dostoevsky can only resort to indirection and example to persuade the reader to accept Zossima’s teaching over the Inquisitor’s.

Whereas the Inquisitor offers miracle, mystery, and authority irrespective of the divinity of Jesus, Zossima offers all three rooted in the experience of divinity as emphasized in Orthodox Christianity and prompted by active love. Zossima’s miracle is illustrated in Alyosha’s vision of the wedding feast in the “Cana of Galilee”; the mystery is the acceptance of responsibility of suffering in our lives, since we are all responsible for each other in a community of believers; and authority is the voluntarily binding of people together in active love and the transformed memory with Christ as their model. Dostoevsky dramatic portrayal of Alyosha and his engagements with Grushenka and the children demonstrate how Zossima’s miracle, mystery, and authority can be realized in a social and political community. By accepting our “Karamazov baseness” as well as the spiritual model that Christ offers, Dostoevsky suggests that a coherent self can emerge and assist in the healing of lacerated individuals who have been cut off and isolated from themselves, others, and divinity. This vision of a Christian and his Orthodox community therefore is the underlying harmony – the “unity in diversity” – that Bakhtin seemed to suggest in his criticism.

The Brothers therefore is not a polyphonic novel in the sense that there is no one view or position privileged over another; rather, the “unity in diversity” that Bakthin had proclaimed can be located in the teachings of Zossima. Furthermore, such a position of polyphony – all diversity and no unity – is clearly repudiated by Dostoevsky’s own personal and public writings. Although Ivan and his Inquisitor may appear to some to be the more attractive than Alyosha or Zossima, it may be a reflection of the reader’s own personal experiences rather than requiring Dostoevsky to furnish a direct refutation to The Tale. Dostoevsky imparted to us a vision of a Christian community based on love, memory, and responsibility that requires the reader to make the necessary connections in the novel, thereby forcing him to reflect upon his own experiences and compare them with the characters in the novel. By challenging us to response to the Inquisitor’s challenge with the material given in the novel, Dostoevsky is asking whether the capacity for active love exists within ourselves and whether, like Alyosha, we have the courage to practice it in our own communities.

Notes

[1] For more about Russian reaction to The Brothers, refer to Kostalevsky, Marina. Dostoevsky and Soloviev The Art of Integral Vision (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1997); and Pattison, George and Diane Oenning Thompson. Dostoyevsky and the Christian Tradition (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001).

[2] For more about Western reception to The Brothers, refer to Wellek, René. “Introduction: A History of Dostoevsky Criticism.” In Dostoevsky (Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall, Inc, 1962); Jones, Malcolm V. Dostoevsky after Bakhtin Reading in Dostoevsky Fantastic Realism (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990); and Cassedy, Steven. Dostoevsky’s Religion (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2005).

[3] Bakhtin, M. M. The Dialogic Imagination, ed. Michael Holquist, tr. Caryl Emerson and Michael Holquist (Austin: University of Texas, 1981); Problems of Dostoevsky’s Poetics, ed. and tr. Caryl Emerson (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota, 1984).

[4] Bakhtin himself never elaborated what this unity was probably because of the restrictions on writing about religious and philosophical subjects in the Soviet Union.

[5] For the influence on Bakhtin on Dostoevsky studies, refer to Jones, Malcolm V. “Dostoevskii and Religion.” In The Cambridge Companion to Dostoevskii, ed. W. J. Leatherbarrow (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002). A sample of different and conflicting interpretations of The Tale are found in Wasiolek, Edward. Dostoevsky: The Major Fiction (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1964); Cox, Roger L. Between Earth and Heaven: Shakespeare, Dostoevsky and the Meaning of Christian Tragedy (New York: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston, 1969); Sutherland, Stewart R. Atheism and the Rejection of God Contemporary Philosophy and The Brothers Karamazov (Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1977); Belknap, Robert. The Genesis of the Brothers Karamazov Aesthetics, Ideology, and Psychology of text-making (Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press, 1990); Knapp, Liza. The Annihilation of Inertia Dostoevsky and Metaphysics (Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press, 1996); Ward, Bruce K. “Dostoevsky and the Hermeneutics of Suspicion,” Literature and Theology, 11 (1997): 270-83; Sandoz, Ellis. Political Apocalypse A Study of Dostoevsky’s Grand Inquisitor (Wilmington, DE: ISI Books, 2000); Anderson, Susan Leigh. On Dostoevsky (Boston: Wadsworth, 2001); Thompson, Diane Oenning. “Dostoevskii and Science.” In The Cambridge Companion to Dostoevskii, ed. W.J. Leatherbarrow (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002); Scanland, James P. “Dostoevsky’s Argument for Immortality,” Russian Review 59 (2000): 1-20; Murav, Harriet. “From Skandalon to Scandal: Ivan’s Rebellion Reconsidered,” Slavic Review 63 (2004): 756-770; and Cassedy, Steven. Dostoevsky’s Religion.

[6] Pattison and Thompson, Dostoyevsky and the Christian Tradition, 6-11; Jones, “Dostoevskii and Religion”; and Frank, Joseph. Dostoevsky: The Mantle of the Prophet, 1871-1881 (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2002).

[7] Translations are mine own from Dostoevsky, F. M. Polnoe Sobranie Sochinenii, ed. G. M. Fridlender et al. (Leningrad, 1972-1990). Subsequent citations will be volume and page number.

[8] Ivan’s “returning God’s ticket” is a rejection of God’s world instead of God Himself. As Dostoevsky wrote to K. P. Pobedonostev on May 19, 1879, “Our socialists today are not concerned with scientific and philosophic arguments against the existence of God (as were the whole last century and the first half of this century); these have been given up. Rather, they are interested in denying as strongly as possible the creation of God, his world, and his meaning. Only in these questions does contemporary civilization find meaning” (4:55-57).

[9] Dostoevsky was familiar with the works of both Roman Catholicism and Protestantism as well as Enlightenment accounts of Christianity. Terras, Victor. A Karamazov Companion: Commentary on the Genesis, Language, and Style of Dostoevsky’s Novel (Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press, 1981), 17; Belknap, The Genesis of the Brothers Karamazov, 21.

[10] Dostoevsky expressed this sentiment in separate letters to his editor, N.A. Liubimov, on May 10, 1879 and to K. P. Pobedonostev on August 24, 1879 (30:1, 63-65, 120-121).

[11] For more about the debates on Dostoevsky’s views on the immortality of the soul, refer to Scanland, “Dostoevsky’s Argument for Immortality.”

[12] Refer to Dostoevsky’s letter of July 16, 1876 (29:2).

[13] Dostoevsky believed that the only viable political solution from a condition of competition over limited resources was a totalitarian state. The possibility of liberalism as a political solution was ridiculed by Dostoevsky in his portrayal of such characters like Miusov. Interestingly, Dostoevsky failed to consider the free market solution as a mechanism to manage social and economic conflict – in fact, he never considered economic solutions in both his personal and public works.

[14] Jones makes a similar point, “This emphasis on the silence of heaven has been associated by some with the apophatic strain in Orthodox theology, according to which the essence of God is unkownable and a sense of the presence of God is to be attained only through spiritual tranquility and inner silence, for which all mental images are obstacles. At all events it harmonises with Dostoevskii’s view that human language is incompetent to express the deepest truths.” Jones, “Dostoevskii and Religion” 170-171.

[15] For more about the role of memory in the novel, refer to Thompson, Diane Oenning. The Brothers Karamazov and the Poetics of Memory (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991).

[16] Cassedy, Dostoevsky’s Religion , 101.

Our review of the book is available here. The following chapters are available here: “Dostoevsky’s Heroines; Or, On the Compassion of Russian Women” “This Star Will Shine Forth From the East: Dostoevsky and the Politics of Humiliation,” and “Dostoevsky’s Discovery of the Christian Foundation of Politics.” Also see “The Apocalypse of Beatitude: Modern Gnosticism and Ancient Faith in Dostoevsky’s The Possessed,” and “Psychologists of Evil: Nietzsche and Dostoevsky on the Darkness of the Soul.”

This excerpt is from Dostoevsky’s Political Thought (Lexington Books, 2013) and was originally published in Perspectives on Political Science, 38: 4 (2009): 197-205.