Reading Augustine’s Confessions in Dalian Labor Camp with Liu Xiaobo

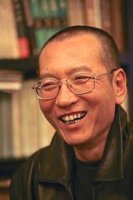

Liu Xiaobo was the Chinese dissident writer and 2010 Nobel Peace Prize recipient who passed away this past June. He died of liver cancer while serving out the eleven-year sentence he received in 2009 for his role in the Charter 08 movement that modeled itself after the Charter 68 movement of dissidents of communism in Czechoslovakia. Liu’s work promoting freedom in China has been compared to similar efforts by Václav Havel, Nelson Mandela, and Aung San Suu Kyi, with the difference being that those figures lived to see their freedom.

Perry Link, the editor of the English translation of his writings of essays and poems, No Enemies, No Hatred, notes that Liu, born in 1955, benefited, paradoxically, from the closure of schools during the Cultural Revolution: “With no teachers to tell him what the government wanted him to think about what he read, he began to think for himself—and he loved it. Mao had inadvertently taught him a lesson that ran directly counter to Mao’s own goal of converting children into ‘little red soldiers.’”[1] Mao’s very attempt to pulverize the Chinese population during the Cultural Revolution and refashion them into “little red soldiers” had the unintended effect in Liu’s case of enabling him to discover freedom and intellectual independence.

This experience is unusual for victims of totalitarianism. So much of their energies are sapped by being forced to live the ideological lie in their soul, as Solzhenitsyn calls it, and the secondary reality of totalitarian rule makes it extremely difficult for them to discern freedom in reality, from their bondage to the lie they must live day in and day out. In her novel, Do Not Say We Have Nothing, whose title is taken from a slogan of the Cultural Revolution, Canadian novelist Madeleine Thien dramatizes the long-term effects of suffering through the ideological lie of the Cultural Revolution and the subsequent struggles of her Chinese characters and their descendants to live in truth. Even so, as with eastern dissident European writers, including Alexandr Solzhenitsyn, the experience of totalitarianism can also have the unintended benefit of enabling a few to discover genuine freedom through suffering.[2] Like them, Liu was able early on to see the lie for what it is. Also like them, he paid dearly for his spiritual and intellectual freedom amidst political bondage.

Liu was remarkable for his intellectual independence and voracious intellectual appetite, including having read the classics of Chinese and Western philosophy. This helped him see through the sophisms of both Chinese and Western intellectuals. But more impressive was his ethical and spiritual outlook. Link writes:

“A visit to New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art had brought him an epiphany: no one had solved the spiritual question of ‘the incompleteness of the individual person.’ Even China’s great modern writer Lu Xun, whose fiction was so good at revealing moral callousness, hypocrisy, superstition, and cruelty, could not, in Liu Xiaobo’s view, take the next step and ‘struggle with the dark.’ Lu Xun tried this, in his prose poems, but in the end backed off; he ‘could not cope with the solitary terror of the grave’ and ‘failed to find any transcendental values to help him continue.’[3]

At the core of Liu’s activities as a dissident was a sustained defence of the transcendent dignity of the person that can only be undertaken in a “struggle with the dark.”

Liu’s own attempt to “struggle with the dark” can be seen in three main ways. First, his repeated insistence on the dignity of the human person reflects his view that each and every individual is an irreplaceable being of infinite worth. This helps explain his fascination with the philosophy of Immanuel Kant, but also with Jesus Christ and, as we shall see, Augustine. All three are subjects of poems he wrote in prison camp. Link writes that, “it was during the three years at labor camp [mid-1990s in Dalian] that Liu Xiaobo seems to have formed his deepest faith in the concept of ‘human dignity,’ a phrase that has recurred in his writing ever since.”[4]

Second, his final statement at his 2009 trial was titled, “I Have No Enemies,” which reflects his magnanimity and indeed forgiveness towards his jailers and prosecutors. This attitude characterizes Mandela, Gandhi, Martin Luther King, Jr., Jesus, and other non-violent resistors he imitated because, as he says in that same statement, “hatred only eats away at a person’s intelligence and conscience, and an enemy mentality can poison the spirit of an entire people.”[5] Hatred destroys societies and individuals. Only love uplifts and only love creates the possibility of society and the bonds among individuals.

Third, he says as well in his final statement that the Tiannamen square massacre of June 1989 was the turning point of his life because it made him into a political dissident. More than that, however, his life as a dissident was an act of atonement for the ghosts of those killed at Tiannamen. He always felt guilty for the relatively light punishment he received at the time, and even more guilty for obliging the authorities by writing a confession, of which he claimed, “in doing that I not only sold out my personal dignity, but betrayed the blood sacrifices of the massacre victims.”[6] He is said to have dedicated his Nobel Prize to the “aggrieved ghosts.” His dissident work was an act of atonement and confession for that light punishment and false confession.

Liu’s dissident activity was a work of confession that revolved around the transcendent dignity of the person, love, and atonement.

One needs to bear these three themes in mind to understand why the volume his translated writings includes a poem, “To St. Augustine,” which he wrote in 1996 in the prison labour camp in Dalian, in his home province of Jilin. It is dedicated to his wife, “Xia, who likes the Confessions.”[7] Link explains that his prison poems must be read “with Liu Xia standing beside him, as it were, as his spiritual companion.”[8] As Augustine offers his confession to God so that he may love God, himself, and others, so too Liu reads Augustine together side-by-side as it were with Xia. His poem is an artifact of his shared vision and contemplation with Xia, an act of intellectual and contemplative triangulation that Aristotle calls sunaisthesis, the peak experience of friendship.[9] For thinkers like Aristotle and Augustine, this experience also makes possible the regeneration of social and political order, of political friendship over and against the spiritual confusion of post-totalitarian regimes.[10]

Liu’s poem is a seemingly irreverent poem that mocks Augustine’s loquacity and wonders whether his writing of the Confessions was more appropriate for a gambler who takes risks on the vicissitudes of time, than for a saint whose greatest virtue, he suggests, must be silence. The poem begins with Liu addressing St. Augustine in the second person pronoun, perhaps as a nod to Augustine’s own innovation in the Confessions of addressing God that way. Liu came to know St. Augustine at the altar by gazing “up at the bishop’s red gown to feel the majesty of the ages.” As Augustine was supplicant before God, Liu presents himself as a supplicant before St. Augustine’s bishopric majesty. He acknowledges the risks Augustine took as a child, citing the pear theft in particular: “I spied a thieving child and knew the joy of risk.”

Liu wonders whether the proclivity toward risk that led Augustine to steal pears and to steal carnal love as a youth is the same love of risk that allowed him to fall “headlong into the arms of God.” St. Augustine’s sins and his saintliness seem to follow the same earthly logic. If so, was his confession sincere? Did it go far enough? Is his confession of his journey to God borne of the same earthly love of risk?

This leads Liu to imagine St. Augustine looking “down upon the grandeur of earth mulling over your humility.” Liu creates a vivid yet ambivalent image. St. Augustine’s humility is grander than the “grandeur of the earth” yet this grander humility might also be prideful, consisting in self-satisfaction in his own creation, his confession, which seems to have overcome the “cruelty and mystery of time” that otherwise rules over us. Again, does St. Augustine’s grandeur imply his confession did not go far enough? Does his confession still play by the earthly logic that it purports to overcome?

Perhaps St. Augustine was the “first to discover the cruelty and mystery of time” and used his confession to escape it into eternal life: “the desire for it may have crushed you, too.” Was his confession a genuine offer of atonement or simply a performance? Moreover was all that effort even worthwhile? Liu the prisoner, with Xia imagined standing beside him, wants to know because he needs to know whether his own sufferings and strivings are worthwhile. In a world characterized by suffering and injustice, where the just seem to suffer more than the unjust, was St. Augustine’s risk worthwhile? Can suffering be redeemed?

These questions get raised implicitly when Liu wonders whether God is even interested in listening to a confession, especially one whose “road to atonement is really that long.” Is God just a “tedious theater-goer” who observes humans “perform offerings of solemnity”? If so, “then the creation myth is nothing but a crude practical joke” because the action on stage is meaningless. St. Augustine though is lucky because even if creation is just a bad joke, even if his and our strivings are in the end meaningless, “in your soul there is another stage and a few puppets,” namely, eternal life.

While St. Augustine may have been lucky, that option of “another stage” does not really help Liu in the prison camp. The poem here reminds one of the scene in Solzhenitsyn’s Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich when Ivan complains to Alyoshka that prayers never help those suffering in the camps. Alyoshka responds that prison is a blessing because it affords one with freedom: “here you can think about your soul.”[11] Liu does not go quite as far as Solzhenitsyn in affirming the blessings that prison provide but the paradoxes and ironies of the poem point in this direction. Indeed Liu’s own activity as dissident seems predicated upon such freedom. This poem then seems to be an attempt to articulate that freedom.

Like Ivan Denisovich, Liu concludes the poem by chiding Augustine’s confidence in his own words, the confidence of his prayer, which is more characteristic of the gambler than of the saint:

But be silent

This is the only virtue of saints

Stones have seen great ruin and are speechless

The sky looks down over all and is speechless

The earth buries all things and is speechless

The meaning of poems, faith, logic

Silver-tongued humanity is a waste

Believing in language is believing Judas’ promise.

Though chiding St. Augustine, Liu implicitly also identifies with him. In writing this poem in a prison, he not only identifies with St. Augustine the fellow author, also like St. Augustine he rejects the suggestion that “the creation myth is nothing but a crude practical joke.” Imprisoned and surrounded by speechless concrete walls and metal bars, the author of the poem titled, “St. Augustine,” reaches up in atonement from the dark pit toward the source that sustains the act of writing confessions, both St. Augustine’s and Liu’s own. The poem, written with Xia at his side, is a confession that takes the form of a reflection upon a confession.

Most commentators suggest Liu was not religious. Even so, “To St. Augustine” is an eloquent testament to a questioning faith in the ground of a reality that nourishes the transcendent dignity of the person, love, and atonement, the ordering principles of Liu’s life as a dissident. Even Liu’s suggestion that St. Augustine’s confession may have been deficient for playing according to the rules of the world it rejects points toward a moral order beyond the world. Even suggesting silence is more appropriate for the saint than believing “in Judas’s promise” in the power of language, while also displaying that same faith in language, points to the logos that undergirds the speech of confession. Even while addressing St. Augustine as he addresses God in his confession, Liu imagines Xia standing beside him as he sits alone in his prison camp, which testifies to the love that sustains our world, making it possible to have “no enemies, no hatred.”

Notes

[1] Perry Link, “The Passion of Liu Xiaobo,” New York Review of Books, July 13, 2017, http://www.nybooks.com/daily/2017/07/13/the-passion-of-liu-xiaobo/?printpage=true

[2] See David Walsh, After Ideology: Recovering the Spiritual Foundations of Freedom, (Washington, DC: Catholic University of America Press, 1995).

[3] Link, “The Passion of Liu Xiaobo.”

[4] Perry Link, “Introduction,” in Liu Xiaobo, No Enemies, No Hatred, trans., Perry Link et al., (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2012), xviii-xix.

[5] Liu Xiaobo, No Enemies, No Hatred, 322.

[6] Liu Xiaobo, No Enemies, No Hatred, 11.

[7] Liu Xiaobo, No Enemies, No Hatred, 240-1.

[8] Link, “Introduction,” xix.

[9] For details, see my The Form of Politics: Aristotle and Plato on Friendship, (Montréal-Kingston: McGill-Queens University Press, 2016), chapters 1 and 2.

[10] For details on Augustine, see my Augustine and Politics as Longing in the World, (Columbia, MO: University of Missouri Press, 2001).

[11] Alexandr Solzhenitsyn, A Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich, trans., Max Hayward and Ronald Hingley, (New York: Bantam Classics, 1963), 141.