Ellis Sandoz as Master Teacher

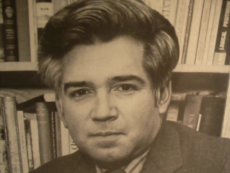

Professor Ellis Sandoz, the Hermann Moyse, Jr., Distinguished Professor of Political Science at Louisiana State University and Director of the Eric Voegelin Institute for American Renaissance Studies, was born in 1931, a descendent of Swiss immigrants who came to Louisiana in 1829. He attended and received a Bachelor of Arts degree in 1951 and a Master of Arts degree in 1953 from Louisiana State University. In 1965 he received his doctorate in political science from the University of Munich under the direction of Eric Voegelin. Professor Sandoz has taught political philosophy at three colleges: Louisiana Polytechnic Institute (1959-1968), East Texas State University–now Texas A & M University-Commerce (1968–1978), and Louisiana State University (1978–present).1In the pasts of many teachers and political philosophers there stands an existential encounter with another philosopher and teacher, in many cases a master teacher, whose character, insight, erudition, intellect, and presence inspired the student to become who he is already.

In other words, the future teacher in the present student is evoked from the encounter with the master teacher. In a sense this existential encounter gives form to the pre-existing, inchoate, unformed teacher, identifying the vocation that student and future teacher is destined to follow. This existential encounter is sometimes so “drastic” that it effects a change in the student, a change that challenges and perhaps inspires that student to fulfill his potential both as a teacher and as a human being.

There are, of course, famous precedents for this model of the teacher-student encounter. One readily calls to mind Plato’s encounter with Socrates and its result: that Plato gave up his intent to become a playwright and politician in order to live the life of a philosopher. Near the beginning of Plato’s Gorgias, Socrates instructs Chaerephon to ask Gorgias Who he is, thereby establishing the crucial question–the existential question–the answer to which will reveal the character of the sophist Gorgias and his student, Callicles. Ultimately, the truth of character–Who a man is–reduces itself to the revelation of what he loves. And what he loves is revealed in those activities in which he engages, for “by his fruits ye shall know him.” Socrates, in opposing the sophist and his student Callicles, now a politician and lover of power, maintains that the philosopher, in contrast, is simply “a lover of wisdom,” for “Only the god is wise.”

The Encounter

In 1949, Ellis Sandoz, an eighteen-year-old undergraduate student at Louisiana State University, encountered an inspiring teacher and philosopher of remarkable character and courage, Eric Voegelin. This encounter determined the path that Sandoz would follow throughout his life and continues to follow today. It would sustain him through his undergraduate years and early graduate work with Voegelin, through his service in the US Marine Corps, and would lead him back to Voegelin in Munich to complete his Dr. oec. publ. It has continued in a massive program of publication, education in the public sphere both here in the United States and abroad, and in a legacy of fostering generations of teacher scholars.

Embedded in this encounter were two fundamental principles that would influence the young Sandoz and move him to philosophical and pedagogical avenues of exploration and discovery. The first of these was Voegelin’s recognition that the primary problem of philosophy is the central human experience of transcendence: the divine-human encounter. In 2002, Sandoz recalled:

“From the time I first heard him lecture as a young undergraduate in 1949, I never doubted that Voegelin was profoundly Christian whatever the ambiguities of his formal church affiliation. It never dawned on me at the time to think otherwise, since the whole of his discourse was luminous with devotion to the truth of divine reality that plainly formed the horizon of his analytical expositions in class and of his scholarly writings as well, as I later found out. That youthful judgment was valid then and, with appropriate qualification, remains so long years later.”2

The second–and perhaps more crucial at least insofar as teaching is concerned–was the principle that the science of philosophy and its central problem of transcendence is controlled by experience. In 2004, again commenting on his encounter with Voegelin as a young undergraduate, Sandoz wrote:

“Voegelin’s teaching method managed to communicate the meditative grounding of his thought. GOD was not a dirty word, and he often stressed to his secular-minded audiences that science is controlled by experience–and you can’t go back of revelation and pretend that pneumatic experiences never happened. This basis of faith was more firmly in place in America, esp. in Louisiana where he taught for 16 years. He was always telling the ‘saving tale of immortality,’ in a variety of ways–out of a conviction that the experience of transcendence is essential to man’s existence as human. This was not argued “religiously” or blandly assumed but buttressed scientifically through the facts of experience.“3

Voegelin’s openness to the horizon of human experience that includes the divine-human encounter:

“often induced students sympathetically to involve their own common sense, intellectual, and faith experiences in understanding demanding material in personal reflective consciousness, somewhat on the pattern of the Socratic imperative: “Look and see if this is not the case.”4

The rooting of science in experience, interpreted by Sandoz as the Socratic “Look and see if this is not the case,” would become the technique through which he would later invite his own students to participate in the philosophical search.

At any rate, it was this encounter that set the student, Ellis Sandoz, on the road to becoming a master teacher himself. It must be made clear, however, that this “setting on the road” is not something that is done to a student in the sense that the student is passive and the teacher is actively intending a particular path for the student. The relationship is much subtler. While the teacher’s intent is certainly to persuade the student of the truth of existence in openness to all realms of reality accessible to him by virtue of his own composite nature, the persuasion itself is rooted in the ability of the teacher to evoke from the student what is already present. Concomitantly, the evocation depends upon the openness and willingness of the students to “involve their own common sense, and intellectual and faith experiences in understanding demanding material in personal reflective consciousness.”5

The Political Philosopher

From the two fundamental principles–that experiences of transcendence are the central focus of philosophizing and that these experiences are subject to validation by every human being–flow other premises central to Sandoz’s political philosophy. In his study of Dostoevsky’s Grand Inquisitor, Sandoz reminds his readers that philosophical anthropology is an essential component of political philosophy. He writes:

“. . . it will be appropriate to recall the pertinence of anthropology and ethics to political theory. The basic connection is of the utmost simplicity. Because political science is a search (zetema) for the truth of things political, it is of necessity concerned with man as human and as citizen (polites) and with the axiological factors which give order and cohesion to the lives of individuals and communities. The science of man is anthropology, and the science of the goods which order human existence is ethics.”6

Sandoz’s anthropology is rooted in Classical Greek philosophy as confirmed, complemented, and completed by Christianity.

Voegelin’s discovery that in Greek philosophy there exists an element of divine revelation and that in the divine revelations of Judaism and Christianity there is an element of reason, led him to the insight that transcendence is the central problem that philosophers must explore, and that the consciousness of an embodied individual human being is the locus of the divine human encounter. It is the human being’s responsibility to fulfill his nature by seeking the Good (Aristotle) or God. As Sandoz writes:

“Through spirit man actualizes his potential to partake of the divin7″e. He rises thereby to the imago Dei which it is his destiny to be. The integrity of the individual human person thus conceived, with its reflective consciousness, is the spring of resistance to evil and responsive source of the love of truth.”7

But there is, however–especially in the Christian tradition that manifests itself in the thinkers of the American Founding–a seamier side to human nature. Man may be a little lower than the angels, and above the beasts of the field, but he is also a fallen creature, and the potentialities of his higher nature–to rise “to the imago Dei which it is his destiny to be”–are often sacrificed to his baser nature. As Sandoz says:

“human beings in addition to possessing reason and gifts of consciousness are material, corporeal, passionate, self-serving, devious, obstreperous, ornery, unreliable, imperfect, fallible, and prone to sin if not outright depraved.”8

A second and crucial element for Sandoz’s political philosophy is what Voegelin called “the Platonic Anthropological Principle” or in Plato’s formulation: The State is Man Writ Large. Voegelin interpreted this principle to mean that the substance of society is spiritual. This means essentially three things: that various dimensions of human nature could be more readily understood if one examined the various parts of the larger entity of the state; that the character of a particular human being could be identified by observing the part of his soul that dominated his actions and thus revealed his character; and finally that the political scientist could judge the nature and type of a particular polis by discovering the character type dominant in that state.

From Plato’s famous construction in The Republic–of the best form of government as the rule of the philosopher-king who embodies Reason (and represents the best human character) and the various degenerating forms of government (and thus less admirable types of humans)–we come to understand that ethics and politics are intertwined. The order of the soul is reflected in the order of the polis and the type of order or disorder that is present in a state determines the type of state. It must also be pointed out that even if the best polis of the philosopher king could be established on earth in historical time, it would always degenerate into its less ordered forms because of refractory human nature.

Plato’s student Aristotle recognized that politics and ethics are intertwined and, while interested in the necessity of the philosophical search for the Highest Good–since all men act to achieve some end and that end is the Summum bonum, catalogued empirically the virtues of the mature man–the spoudaios–of Athens. In his great works on ethics and politics–the Nicomachean Ethics and Politics–he defined politics as a prudential science and thereby focused attention on the possibilities of establishing the best form of government possible given the circumstances of a particular society. Recognizing Aristotle’s maxim that politics is a prudential science, Sandoz tempers his defense of the politics of truth by asserting that:

“truth’s blazing luminosity cannot sustain itself perfectly given the facts of refractory historical existence, not least of all the vividly attested mystery of evil. The politics of truth thereby implies some degree of prudential tempering, if it is not to succumb to perversion. It is there that the idealist becomes impatient, indignant, or even disgusted with the statesman. Compromise appears to be necessary, and this always seems an unwholesome business.”9

Addressing the faculty at the University of Palacky, Czech Republic, Sandoz argues that “if we can acknowledge that politics is art as well as science, and that even as science it can never be more precise than its subject matter permits [Aristotle], we set foot on the road to sound government.”10

A third element of Sandoz’s political philosophy is his focus on human liberty and its corollaries: liberty under law, individual freedom, and personal responsibility. As one of his students Jeremy Mhire puts it:

“One knows two things about Ellis: Voegelin and America. How and why he reconciles the two the way he does is a question for his immense contributions to scholarship. One has the sense that Voegelin taught Ellis to see that the best of American political thought and practice opened up to, indeed was a contributing part of, the openness and true freedom that is preserved in and through western civilization.”11

Mhire’s “sense” that Voegelin enabled Sandoz to see the importance of America’s historical contribution to western civilization is accurate, I think, for Voegelin saw that his establishment of the Political Science Institute at the University of Munich, provided him the opportunity to build “curriculum that had at its center the courses and seminars in classical politics and Anglo-American politics with the stresses on Locke and the Federalist Papers.”12

Sandoz found in his own tradition a ready field for exploration and development. In his essay, “Reflections on Spiritual Aspects of the American Founding,” he wrote that “the founding was the re-articulation of Western civilization in its Anglo-American mode.”13 In his study of this period he came to appreciate the important contributions that the itinerant preachers–in addition to the revolutionaries and constitution-makers–made to the development of a civic consciousness. He writes in “Foundations of American Liberty and the Rule of Law” that

“Undergirding all of the “events” [of the Founding period] lay a concerted education of the general populace of America in the political theory and jurisprudence of liberty and rule of law that created the civic consciousness of citizenship essential to the formation of civil community or society and to the foundation of the nation. It seems likely to me that the origins of a national American community with a special destiny in world history lay in the work of George Whitefield and other itinerant preachers who crisscrossed the country for decades, bring the Great Awakening to America from 1739 onwards, sporadically right into the Revolutionary and constitutional periods.”14

Forming the bedrock upon which this education of the general public was built is a Christian anthropology that articulates the experiences of having been created–Sandoz often reminds his students that “We live in a house we didn’t build”15–and of being free beings. Introducing his anthology of political sermons of 18th century America, he writes that the itinerant preachers saw:

“Man, blessed with liberty, reason, and a moral sense, created in the image of God, a little lower than the angels, and given dominion over the earth (Psalm 8; Hebrews 2:6-12), [as] the chief and most perfect of God’s works. Liberty is, thus, an essential principle of man’s constitution, a natural trait which yet reflects the supernatural Creator. Liberty is God-given. The growth of virtue and perfection of being depends upon free choice, in response to divine invitation and help, in a cooperative relationship. The correlate of responsibility, liberty is most truly exercised by living in accordance with truth.”16

Since human beings are “flawed” creatures in addition to being free, they require governance that will assure their liberty because “among the chief hindrances to this life of true liberty is the oppression of men.”17 “The trick of politics and the demand of statesmanship,” Sandoz says, in obedience to the principles of Aristotelian prudential science:

“. . . are to embody the idea–truth and justice–in recalcitrant human reality within tolerable limits . . . . Experience–the culture of habit and the institutions available to the society and its political leadership–is generally a limiting factor, but the particulars always are decisive. In fact, the plausibility of the argument in favor of the rule of law rather than of men always has been that law is the distillation of reason and justice. But men possess an element of the beast, so that anger and passion pervert the minds of rulers, even when they are the best of men. Aristotle first said this, and James Madison and the American founders believed him and partly based their constitutional design on separated powers with checks and balances on the validity of this anthropology.”18

If we consult Professor Sandoz’s students about his political philosophy, we find that they clearly understand both the content and intent of his teaching. Scott Segrest recalls:

“Despite, or perhaps in a sense because of, the mystical overtones of Sandoz’s treatment of spiritual foundations, he is, as Adams was, a hard-headed realist about human affairs, emphasizing human limitations and the human proclivity to vice, corruption, and, all too often, outrage. When Sandoz is hopeful, he is always cautiously hopeful. When he celebrates Western and American achievements, as he often does, his praise is almost always qualified and he never lets us forget the tenuousness and fragility of the hard-won benefits. Sandoz has no trace of Jeffersonian enthusiasm for revolutionary projects. If he strives to keep us in mind of transcendence, he knows, with Madison, that men are no angels. The result of all this is a political philosophy that is at once inspirational and bracingly sober. I can think of no contemporary scholar who has so consistently struck the right balance of hope and solid common sense.”19

Nicoletta Stradaioli, a researcher at the Eric Voegelin Institute and an advisee of Professor Sandoz, describes his work as an “alliance of philosophy and faith, of mind and spirit”:

“By means of thorough study of the American Founding, focusing on the themes of liberty, liberty under law, religion and the role of classical ideas in American Republicanism, Professor Sandoz reveals the perennial questions of human nature. Sandoz’s interpretation of the Founding Fathers’ vision of political reality examines the Classical and Christian roots of their thinking emphasizing how the American Founders strengthen the notion of the individual human person as possessed of certain inalienable rights that are God-given in an indelibly defining creaturely-Creator relationship. Thus, the general understanding of human existence hints at a human being living in truth under God. A human being’s vertical tension toward transcendent divine reality has a horizontal form of action in history that is best exemplified by the American Founding political thought.”20

Sandoz’s encounter with Voegelin not only evoked from him his vocation, supplied the principle of experiential validation, and led him to develop his own political philosophy, but also led him to carry his personal commitments beyond his activity as a scholar of political philosophy: it led him to embrace the Truth and to resist the Lie.

There are, however–even within Sandoz’s and Voegelin’s commitment to Truth–many truths within the Truth of Existence. We recall here Voegelin’s principle that ordering experiences of divine-human encounters in various traditions are equivalent even if the symbolizations of these are linguistically and metaphorically different.21 We may also note, as does Sandoz, that Voegelin often referred to Jean Bodin’s caution against religious intolerance. Sandoz writes that:

“. . . the insistent exclusivity of putative Christian (doctrinal) truth, Voegelin tempered with the mystic’s tolerance as expressed by Jean Bodin who wrote: ‘Do not allow conflicting opinions about religion to carry you away; only bear in mind this fact: genuine religion is nothing other than the sincere direction of a cleansed mind toward God.'”22

Finally, we must heed Sandoz’s qualification and warning about Truth:

“No truth is immune if dogmatically insisted upon . . . . Truth as grasped in human cognition is, thus, neither monolithic and doctrinaire nor comprehensive. The truths of the human realms of time and space, historical truth, must be distinguished from eternal or everlasting verity. Even under the best of circumstances, human knowledge achieves no more than representative truth grounded in the perspective of participation, and it is never the comprehensive Truth of omniscience.”23

Sandoz’s own resistance to untruth has taken two forms.

First, his resistance has taken the form of research and publications that have included not only his explication of Voegelin’s philosophical work, but also his own extensive work on the Anglo-American historical tradition of resisting tyranny in the name of liberty under law. Included are the political philosophers and lawyers who buttressed and aided this struggle for freedom; the thought of the American Founders themselves; and, finally the contributions of the religious leaders of the American Founding to a civic consciousness that supported the establishment of a political system based upon the principles of liberty under law, individual freedom, personal responsibility, and constitutional limitations upon the exercise of power. Although various publications of Professor Sandoz report his findings, three collections of his essays–A Government of Laws: Political Theory, Religion, and the American Founding; The Politics of Truth and Other Untimely Essays; and Republicanism, Religion, and the Soul of America–give ready access to the range of his research.24

The Teacher

Upon this extensive research he has built a second tier of resistance to untruth that is more “politically” active although educational in form. In both his classroom and in the educational conferences that he has organized, directed, and participated in he has relied upon a combination of Classical Greek, Christian, Voegelinian, and Anglo-American writings. And in both of these educational venues, the primary aim is to persuade his interlocutors of the Truth of Existence–not as he himself formulates it, but as they experience it with his help and support. The teacher-philosopher must:

“ineluctably live the open quest of truth, however, as a participant in the In-Between or metaxic common divine-human reality: there is no Archimedean point outside of reality from which to objectively study it, nor is the leap in being or experience of the transcendent Beyond a leap out of the abiding reality of the human condition . . . .Thus, within the limits of possibility and persuasion, the philosopher is called actively to resist untruth through searching noetic critique, grounded as is Aristotle in robust common sense which is the foundation of prudential rationality and of political science itself . . . . “25

The teacher becomes the model of resistance to untruth, but persuasion is not a rude imposition upon the students or interlocutors to accept every word out of his mouth as absolute. Instead, the student must be invited to “Look and see if this is not the case” and thereby be included in the philosopher’s search and resistance. The student must freely respond to the invitation and enter into the search for truth in a free and open exchange of ideas. As Sandoz says in his Teaching Philosophy, “true education is always self-education.” The teacher cannot persuade the student to the truth, only the student can discover the truth when he truly looks into and explores his own consciousness.

This mode of teaching is risky because it depends absolutely on the spiritual authority of the teacher. And the spiritual authority of the teacher must be firmly grounded in the love of the Good and the genuine respect for the individual person of each student that comes of this love. If the former is not present the latter will be absent also. Randy LeBlanc confirms that Sandoz demonstrated in his seminars his respect for students:

“he allowed, in fact insisted, that students follow their own trains of thought before bringing them back to the matter at hand. He appreciated the work of philosophy, and he did not have to agree with a student’s perspective in order to respect the student and his or her work.”26

Professor Sandoz’s philosophical vocation as demonstrated to him by Voegelin–“to love the Good, to serve the truth of Being in its highest dimensions, [to] live in attunement with it, and to resist untruth”27–inspired him to engage in a number of activities that honor the legacy of his mentor in numerous ways. While some of these activities occur outside the traditional classroom, they are rooted in the conviction that in a free society it is essential that scholars address the philosophical underpinnings of politics and that it is their obligation to encourage the development of a civic consciousness that grounds liberal democratic political systems in “self-evident truths.” These activities include his organizing and leading the Eric Voegelin Society as a related group of the American Political Science Association (usually abbreviated APSA), his conceiving and persuading Louisiana State University to establish the Eric Voegelin Institute for American Renaissance Studies, and his participation in Liberty Fund conferences.

The Eric Voegelin Society

In 1985, Sandoz led the movement to found the Eric Voegelin Society. Sandoz assumed the leadership of the Society and in his role as Secretary, began organizing programs that first met in 1986 in conjunction with the annual APSA convention. There were two panels that first year. Over the intervening years since then, Sandoz has organized 26 annual programs which have presented 180 panels. From 1986 through 2011 these programs have included over 400 individual scholars. Even though many of the panels and papers over the years have focused on interpreting the work of Eric Voegelin, its relation to various philosophers and religious thinkers, as well as its implications for contemporary politics, Professor Sandoz has invited any scholars who wish to discuss the philosophical dimensions of politics to submit panel and paper proposals.

The Eric Voegelin Institute

In 1987, the Board of Supervisors of Louisiana State University, with a initial $50,000 grant from the Exxon Foundation secured by Sandoz, established the Eric Voegelin Institute for American Renaissance Studies and appointed Professor Sandoz as its Director. After the initial establishment of the Institute, Sandoz continued to raise funds–reaching an apex of $10,000 per month for a time–to support the various activities and publishing ventures sponsored by the Institute. In order to support the work of the Institute, Sandoz has continued to secure funds from benefactors–individual, corporate, and foundational. In 2009, for example, he secured for the Institute major grants from Earhart Foundation and the Hamel family totaling $40,000.28 The bulk of the funds Sandoz has generated for the past twenty-five years has supported the varied works of the Institute, to include various publication projects as well as the sponsorship of several conferences held in Eastern European nations after the dissolution of the Soviet Union.

The Eric Voegelin Institute Publishing Program

The primary publication endeavor supported by the Eric Voegelin Institute was The Collected Works of Eric Voegelin. With Sandoz serving as general editor, thirty-four volumes were prepared and published over more than a twenty year period. In addition, he also edited and wrote introductions for six volumes from 1990 to 2006.29 Each volume of the Collected Works received a subvention from the EVI to support its publication. Beverly Jarrett, former Director of the University of Missouri Press wrote:

“Sandoz led the editorial board and me as we laid out plans for publication of the thirty-four volume Collected Works of Eric Voegelin, [and] it is . . . appropriate to record the fact that Ellis Sandoz was the one human who worked hardest to assure that The Collected Works was not allowed to falter. Whether it was volume editors, translators, a dedicated publisher, or money that needed to be secured, it was Ellis Sandoz who worked tirelessly to locate those necessities.”30

Under the leadership of Sandoz, and in conjunction with the University of Missouri Press, the Institute also established two monograph series entitled Eric Voegelin Institute Studies in Political Philosophy ( 26 volumes published to date) and Studies in Religion and Politics ( 7 volumes published to date). Each of these volumes received a subvention from the Institute to support its publication. The Institute also supplied monetary support for copy-editors and indexers for many of these monographs.

Eric Voegelin Institute Conference Organization, Direction, Participation, and Support

After the Soviet Union disintegrated and the Eastern European nations were liberated from Soviet dominance, Ellis Sandoz, as Director of the Eric Voegelin Institute, seized the opportunity to organize and direct conferences focusing on liberty, law, and constitutionalism in Czechoslovakia and Poland. The first of these, Anglo-American Liberty, Constitutionalism and Free Government: A Workshop on The Federalist Papers, was sponsored by the Institute under contract to the United States Information Agency and held in Moravia, Czech & Slovak Federal Republic in 1991. The second, Anglo-American Liberty, Constitutionalism and Free Government: John Locke and the Foundations of Modern Democracy, was sponsored by the Institute in cooperation with the Jan Hus Foundation, and held at at Palacky University, Olomouc, Czech Republic in July 1992. The third, Anglo-American Liberty, Constitutionalism and Free Government: A Workshop on The Federalist Papers, was sponsored by the Institute in cooperation with the Jagiellonian and Kosziusko Foundations at Jagiellonian University, Krakow, Republic of Poland in July 1992.

Eric Voegelin Institute Scholarship Program

Numerous students of political theory have received Institute scholarships that supported their graduate studies. For example, from Fall, 2008, through Spring, 2011, the Institute awarded assistance to students from the Eric Voegelin Scholar Fund and the Sidney Richards Moore Fellowship in Political Philosophy.31 In addition, Professor Sandoz has generously supplied travel stipends from Institute funds for students to attend various domestic and international conferences.

Liberty Fund Conference Organization and Participation

Since 1985, Professor Sandoz has organized for the Liberty Fund32 twenty-seven conferences focusing on readings as disparate as classical Islamic texts, the Magna Carta, St. Augustine, St. Bonaventure, Milton, Leo Strauss, and Eric Voegelin. In addition, he organized and participated as a discussant in three Liberty Fund conferences that were held in the Czech Republic, to wit “Crisis, Liberty, and Order” in 1994, “Rule of Law, Liberty, and Civic Consciousness” in 1995, and “Montesquieu and Burke on Constitutionalism, Liberty and Human Nature” in 1996.

The Students

While these varied activities grow naturally from Professor Sandoz’s encounter with Eric Voegelin and the subsequent development of his political philosophy, the most important outcome (and the reason for this essay) is what Professor Sandoz does in the classroom. Below I describe the instrumental elements–principles that he identifies as part of his teaching philosophy, readings that he requires in his courses, and the general demands that he makes upon his students–of his teaching, followed by a description of his teaching techniques and classroom presence as reported by his students.

In his Teaching Philosophy Sandoz identifies three principles as central to his teaching: “the student is the most important person in the classroom,” “all education worthy of the name is self-education,” and “a professor bears the name because he or she professes something, and that something is the scholarly ascertained scientific truth of the course subject-matter under discussion as the objective content of instruction.” Expanding on the third principle Sandoz insists that the professor must know his business and be prepared to “use all appropriate means to provoke interest, to respectfully engage the critical faculties of each and every student in class and to push them beyond their own suspected limits.”33

Sandoz indeed makes rigorous demands upon his students:

“reading sources beyond the textbook and lecture coverage, and writing analytical essays at test and exam times were (and are) required, and making an ‘A’ is a distinct challenge. Since I respect the material I teach, the writings we study together, I expect students to respect it also and to do their best to understand and master it.”34

The most challenging aspect of Sandoz’s courses are the extensive and difficult readings. For example, the reading list of his undergraduate ancient and medieval political theory includes five dialogues by Plato; Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics and Politics; Thomas Aquinas’ Political Ideas; St. Bonaventure’s Journey of the Mind to God; Edward S. Corwin’s Higher Law Background of American Constitutional Law; and Sir John Fortescue’s On the Laws and Governance of England. Student grades in the course are then based upon two essay exams covering the readings and lectures and the final essay examination that is cumulative. The difficult of the reading lists and assignments however is complemented by the approaches that Sandoz takes in classes.

Fundamental to Sandoz’ basic approach is his unwillingness to impose his own ideas on students. Rather, he encourages them to think through political and philosophical problems with his help and support. Angela Miceli appreciates this openness in Sandoz’s teaching. She writes that:

“I always sensed that Dr. Sandoz put the care of students first. He has been a model of what a teacher is called to do: to serve. Ellis was never the type of self-aggrandizing professor who shoved his own opinion or ideology into his student’s brains, nor did he ever demand their allegiance to his beliefs or interests.”35

Not only does Sandoz refuse to impose his own opinion on students, he also urges them to think for themselves. Scott Robinson confirms the openness that Miceli appreciates in Professor Sandoz. Robinson recalls:

“as far as the teacher-student classroom relationship was concerned, I did not know what Professor Sandoz’s political philosophy was, precisely because Professor Sandoz was encouraging me to develop my own political philosophy: to think through political issues on my own and not become an ideological drone. Of course, his appreciation for classical philosophy, the truth, reasonableness, etc, could not be missed. It is, however, his open-minded appreciation for these ideals that is most note-worthy.”36

And even though Sandoz often uses Voegelin’s work in courses, he neither imposes his own interpretations of Voegelin on his students nor does he impose on them Voegelin’s own interpretations of other texts. As one of his students, Glenn Moots, notes: Sandoz “would not only abide non-Voegelinian readings of texts, he assigned texts that Voegelin himself considered unoriginal or even dangerous and taught students to appreciate the virtues of those texts . . . . He wasn’t interested in transmitting a Voegelinian orthodoxy.”37

Over the fifty-two years of his teaching career, students have responded to Sandoz’s demands by committing themselves to demonstrate to him that they can excel on his assignments. One former pre-law student, Steve Cowan, recalls that in his first class with Sandoz, he earned a B+. Since this grade did not fulfill his own desire to make A’s in order to bolster his chances of being admitted to law school, he signed up for Russian Political Theory in order to prove to himself and Sandoz that he could make his A. After doggedly studying all the texts, class lectures, and suggested readings, after reciting the whole course back to Sandoz, he had written 20 pages in pencil (because he could write faster) and only finished the first of two required essays. He was sure that he had blown his chances for an A.

Forty years later he remembers:

When Dr. Sandoz came in with the graded papers, he told the class that he didn’t give A pluses, but if he did, he would have given one this time. I received my test back with an A in red pencil at the top with one word written on the paper, ‘Able.’ Just A-B-L-E. That one word comment from a teacher I admired has stuck in my brain for 40 years. I have used it to encourage my sons and even used it to describe a retiring judge after a long and distinguished career. I suppose he knew I could have answered question two if I had managed my time better. In the margin, he wrote ‘next time don’t use a pencil.’48

Although Sandoz does not overtly acknowledge that he is in the business to help students “complete the building of their souls,”49 the students recognize that his teaching addresses the spiritual dimensions of their individual humanity and that he is genuinely concerned that they live good lives. Nicoletta Stradaioli writes that “Professor Sandoz highlights a responsible personal way of living and the moral and political principles (human dignity, morality of liberty and justice . . . ) that an individual has to accomplish for an ordered societal existence.”50

Todd Myers emphasizes that:

“the material he brought to class was existentially significant. It was meant to engage the learner in the process of soul building. If I understand his role as teacher correctly, his understanding of a liberal education was to equip people for the spiritual journey of a human life while meeting the material needs of that life. Completely balanced . . . That is the mark of a great teacher.”51

David Whitney observes that Sandoz’s teaching method, following Aristotle, begins “with common opinions about the topics covered and tries to move the student beyond those opinions to get at the truth of the matter [and] he is adamant about the importance of ‘checking’ reason with experience. The two must go together. Citing Socrates, he always implores the students to “look and see if it’s the case.” In other words, check your own experience52:

“Paideia, of course, is dependent upon persuading the students to become active members in their own education by inviting them, as well as often reminding them, to check the ideas found in their texts or discussed in class against their own experience. When students are invited to ‘Look and see if this is not the case’ they know at an experiential level that they too can become participants in ‘the great dialogue that goes through the centuries among men about their nature and destiny.’”53

Jeremy Mhire observes that Sandoz’s:

“. . . teaching philosophy involves getting students to see for themselves what is, and what is not, worth preserving. That includes acquiring a vast acquaintance with canonical texts, as well as an ever-deepening understanding and appreciation of history.”54

This is a very powerful and liberating experience for students know that they are engaged for a lifetime in the work that Sandoz has invited them into.

Scott Robinson recalls:

“I had and still have the impression that Sandoz cares more about the well being of his students than he cares about any idea in particular; this is a healthy and hopefully infectious state of mind. If Sandoz’s students teach their students the way that Sandoz taught us . . . well, if one follows this train of thought through, one cannot help but see the tremendous potential good to be wrought from Professor Sandoz’s character and efforts.”55

Angela Miceli experiences Sandoz’s teaching as joyful guidance through complex and difficult readings. She writes that he:

“has a way of making the truth very relatable to common human experience, and yet he is guided by the highest mystic thinkers and writers. He encourages students not to fear engaging these thinkers and joyfully guides them through texts to discover the truth about what it means to be a human person living in the world.”56

Not only does Sandoz guide his students through difficult texts, but he also demonstrates the significance of the formative effects of the classical works of western civilization in his own life. One student from the 1970s, in an unsolicited message sent to Sandoz in 2008 wrote:

“When I was in college I did not attend church regularly, but one Sunday I attended First Baptist Church in Commerce and you were there. I don’t know anything about your religious beliefs then or now, but your presence at church said a great deal to me. It said that if a man with a mind and an education like Dr. Sandoz can have a place for God in his life, then I, too, can have a healthy life of both the mind and the spirit.”57

Finally, it is the existential commitment of Professor Sandoz that impresses upon his students the essential importance of philosophy, understood as the love of wisdom, of the Good, of God, for both personal and social order. Indeed, it is from the integration in his person of Classical Greek Philosophy and Christianity, a union taken to heart from the example of his own teacher in 1949, that students learn they too can “have a healthy life of both the mind and spirit.”

Notes

1. Acknowledgements and a Note on Sources.

Professor Sandoz was kind enough to send me a wealth of information to include: a list of all the graduate students whose theses and/or dissertations he directed, students’ narrative responses from various course evaluations, course syllabi, a copy of his Teaching Philosophy, a copy of the 2010 Report of the Eric Voegelin Institute to the administration of Louisiana State University, copies of e-mails or letters sent to him by former students, and a copy of his Curriculum Vitae that includes his various teaching-related activities in addition to a bibliography of his publications.

Much of this information was already known by me (especially his publications, his work with the Eric Voegelin Institute at LSU, and his work with the Eric Voegelin Society), but to have it in a consolidated form and in one place was quite helpful. Steve Ealy, Senior Fellow, Liberty Fund, Inc., graciously answered my questions about Liberty Fund conferences and supplied me with a list of the Liberty Fund Conferences that Professor Sandoz conceived and organized.

Information describing Sandoz’s teaching–its nature and impact with illustrations –was solicited from former students in the form of “interviews.” These “interviews” consisted of sending six open-ended question-prompts to his students asking them to respond in writing and e-mail these responses back to me. In addition to those responses solicited by me from his students, Professor Sandoz sent me several unsolicited “testimonials” sent to him by former students. I would like here to acknowledge and thank all of the students of Sandoz who responded to my questionnaire for their thoughtful, insightful, and extensive narratives. Even though I have not been able to use all of the material they generously supplied to me, all of the responses contributed to what, I hope they will agree is an accurate portrait of their teacher.

Finally, I thank my wife, Polly Detels, for her invaluable help in revising and editing this essay for publication. Of course, all the mistakes and missteps that squeak through remain my responsibility.

2. Ellis Sandoz, “Carrying Coals to Newcastle: Voegelin and Christianity,” 1. Voegelin and Christianity: A Roundtable. American Political Science Association and Eric Voegelin Society, Annual Meeting, Boston, August 30, 2002. Accessible at http://www.lsu.edu/artsci/groups/voegelin/society/. A slightly revised version of this paper appears in Ellis Sandoz, Republicanism, Religion, and the Soul of America. (Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 2006), 114-120.

3. Ellis Sandoz, “Eric Voegelin as Master Teacher: Notes for a Talk,” 2-3. Roundtable Discussion, American Political Science Association and Eric Voegelin Society, Annual Meeting, Chicago, September 4, 2004. Accessible at http://www.lsu.edu/artsci/groups/voegelin/society/.

4. Ellis Sandoz, “Eric Voegelin as Master Teacher: Notes for a Talk,” 2-3.

5. Ellis Sandoz, “Eric Voegelin as Master Teacher: Notes for a Talk,” 2-3.

6. Ellis Sandoz, Political Apocalypse: A Study of Dostoevsky’s Grand Inquisitor. (Wilmington, Delaware: ISI Books, 2000), xvii-xviii.

7. Sandoz, “Carrying Coals,” 2.

8. Ellis Sandoz, “The Politics of Truth,” in Ellis Sandoz, Politics of Truth and Other Untimely Essays: The Crisis of Civic Consciousness (Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 1999), 39.

9. Sandoz, The Politics of Truth, 38.

10. Sandoz, The Politics of Truth, 40.

11. Jeremy Mhire (student 2000-2006), personal e-mail communication to me, July 25, 2011.

12. Quoted by Sandoz, “Eric Voegelin as Master Teacher,” 2.

13. Ellis Sandoz, “Reflections on Spiritual Aspects of the American Founding,” in A Government of Laws: Political Theory, Religion, and the American Founding, (Columbia: Unversity of Missouri Press, 2001), 151.

14.Ellis Sandoz, “Foundations of American Liberty and Rule of Law,” in Republicanism, Religion, and the Soul of America (Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 2006), 57.

15. Joshua Deroche (present student), personal e-mail communication to me, November 28, 2011.

16. Ellis Sandoz, ed. Foreword. Political Sermons of the American Founding Era, 1730-1805. Volume 1. (Indianapolis: Liberty Fund, Second edition, 1998. Foreword, 1991), xvii-xviii.

17. Ibid., xvii.

18. Ellis Sandoz, “The Politics of Truth,” 39.

19. Scott Segrest (student 1998-2005), personal e-mail communication to me, July 26, 2011.

20. Nicoletta Stradaioli (researcher and advisee at Eric Voegelin Institute 2001; 2005-2008), personal e-mail communication to me, July 23, 2011.

21. Eric Voegelin, “Equivalences of Experience and Symbolization in History,” in volume 12, Published Works, 1966-1985, ed. with introduction Ellis Sandoz, Collected Works of Eric Voegelin, (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1990), 115-133.

22. Sandoz, “Carrying Coals to Newcastle,” 8.

23. Sandoz, “Politics of Truth,” 40.

24. See attached Selected Bibliography of Published Works by Ellis Sandoz.

25. Sandoz, “The Philosopher’s Vocation: The Voegelinian Paradigm,” Review of Politics 71 (2009), 57.

26. Randy LeBlanc (student 1993-1997), personal e-mail communication to me, July 22, 2011.

27. Ellis Sandoz, “Mysticism and Politics in Voegelin’s Philosophy,” American Political Science Association and Eric Voegelin Society, Annual Meeting, Toronto, Ontario, Canada, September 4, 2009. Accessible at http://www.lsu.edu/artsci/groups/voegelin/society/.

28. Summary Report of Activities, Eric Voegelin Institute 2009 as Updated for 2009-2010, 2.

29. See attached Selected Bibliography of Published Works by Ellis Sandoz for specific volumes.

30. Beverly Jarrett, “Publisher’s Note,” in Charles R. Embry and Barry Cooper, eds., Philosophy, Literature, and Politics: Essays Honoring Ellis Sandoz, (Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 2005), vii.

31. Summary Report of Activities, Eric Voegelin Institute 2009 as Updated for 2009-2010, 4.

32. The Liberty Fund Foundation, founded by Pierre F. Goodrich in 1960, sponsors small scholarly conferences that include participants from various occupations and academic disciplines to include economics, history, law, political thought, literature, philosophy, religion and the natural sciences. Mr. Goodrich, who read widely in the Great Books, tradition believed “that education in a free society requires a dialogue centered in the great ideas of civilization. He saw learning as an ongoing process of discovery, not limited to traditional institutional settings or specific ages.”

These conferences are organized to promote Goodrich’s conviction “that the best way to promote the ideal of a society of free and responsible individuals is through [a] full and open [Socratic] discussion among people of varying ages, backgrounds, and occupations.” This information was accessed at the Liberty Fund, Inc. site (http://www.libertyfund.org here) on various days, the last being December 7, 2011.

33. Ellis Sandoz, “Teaching Philosophy,” October 2007.

34. Ellis Sandoz, “Teaching Philosophy,” October 2007.

35. Angela Miceli (student 2005-2011), personal e-mail communication to me, July 25, 2011.

36. Scott Robinson (student2002-2006), personal e-mail communication to me, June 17, 2011.

37. Glenn Moots (student 1991-1993; 2000-2001), personal e-mail communication to me, June 17, 2011.

38. Alan Baily (student 1999-2003), personal e-mail communication to me, July 20, 2011.

39. John Baltes (student 1994; 1998-2002), personal e-mail communication to me, July 17, 2011.

40. Ibid.

41. Randy LeBlanc (student 1993-1997), personal e-mail communication to me, July 22, 2011.

42. Scott Robinson (student 2002-2006), personal e-mail communication to me, June 17, 2011.

43. Angela Miceli (current student), supplied as a supplement to her personal e-mail communication to me, July 25, 2011.

44. Scott Segrest (student 1998-2005), personal e-mail communication to me, July 26, 2011.

45. Sam Whitley (student 1970-1972), personal e-mail communication to me, June 17, 2011.

46. Scott Robinson (student 2002-2006), personal e-mail communication to me, June 17, 2011.

47. Todd Myers (student 1992-1997), personal e-mail communication to me, July 17, 2011.

48. Steve Cowan (student, 1971-1972), personal e-mail communication to me, November 28, 2011.

49. Werner Dannhauser, “On Teaching Politics Today,” Commentary, March 1975, 74.

51. Nicoletta Stradaioli (researcher and advisee at Eric Voegelin Institute 2001; 2005-2008), personal e-mail communication to me, July 23, 2011.

51. Todd Myers (student 1992-1997), personal e-mail communication to me, July 17, 2011.

52. David Whitney (student 2004-2010), personal e-mail communication to me, July 17, 2011.

53. Eric Voegelin in letter to Robert B. Heilman, August 22, 1956 in Charles R. Embry, ed. Robert B. Heilman and Eric Voegelin: A Friendship in Letters, 1944-1984 (Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 2004), 157.

54. Jeremy Mhire (student 2000-2006), personal e-mail communication to me, July 25, 2011.

55. Scott Robinson (student 2002-2006), personal e-mail communication to me, June 17, 2011.

56. Angela Miceli (student 2005-2011), personal e-mail communication to me, July 25, 2011.

57. A copy of this e-mail message was supplied to me but I have withheld the name of the writer because my attempts to contact him have be.

Also available are works about teaching: Introduction, Eric Voegelin, Ellis Sandoz, Gerhardt Niemeyer, John H. Hallowell, Leo Strauss, Harvey Mansfield, Stanley Rosen, and Conclusion; also see John von Heyking’s and Lee Trepanier’s “Teaching Political Philosophy“; Brendan Purcell’s “Eric Voegelin as Master Teacher“; Thomas Holloweck’s “Eric Voegelin as Master Teacher“; and John von Heyking’s “Periagoge: Liberal Education in the Modern University.”

This excerpt is from Teaching in an Age of Ideology (Lexington Books, 2014)