Seamus Heaney and the Metaxological Narrative

The goal of this series of essays is the illumination of individual poems as metaxic spaces. Readers of Voegelinview will recall Glenn Hughes’s ground-breaking essays on Emily Dickinson in this regard. Voegelin’s “In Search of Order” (2000) introduced us to the depths of the discourse of the metaxy: our plunging footprints darken his snow. Second, William Desmond has explored “the between” in a long series of works, and they remain essential reading, especially God and the Between, where the narrative of the metaxy becomes quite clear. Finally, drawing on the work of Cyril O’Regan (including his essay on William Desmond in Between System and Poetics: William Desmond and Philosophy After Dialectic, 2007), we seek to show how the narrative grammar of the metaxy makes possible the recognition of a diversity of metaxies in poetry. Since the publication of Voegelin’s last book in 2000, a new map of poetic form, a new metaxological poetics, has seemed possible. These essays are in earnest of such a project.

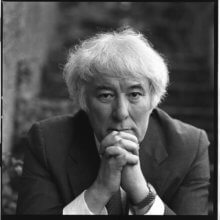

Seamus Heaney was one of the great poets of the 20th century. Born on a farm in County Derry in 1939, and has written often about his Catholic upbringing in rural Ireland. Eventually, Heaney became recognized the world over for his poems, translations, and critical essays. From 1989 to 1997 he was Professor of Poetry at Oxford. From 1981 to 2006, he was professor at Harvard. In 1995 he won the Nobel Prize for Literature. He died in 2013. Among his outstanding achievements was to use poems to explore the human spirit in history; his translation of the Medieval epic Beowulf became a bestseller. Early in his career he framed the Irish Troubles in light of prehistoric violence as well as universal ethical and existential themes. His late poetry, dismissed by some as too discursive, is particularly lucid as meditation on metaxological reality. He once said that when he was composing the poems that appeared in Seeing Things (1991), he lived somewhat reclusively, enjoying a break from public duties; among the books he studied then was Jacques Maritain’s Creative Intuition in Art and Poetry. The poem I analyze below is from this book.

Deserted harbour stillness. Every stone

Clarified and dormant under water,

The harbour wall a masonry of silence.

Fullness. Shimmer. Laden high Atlantic

The moorings barely stirred in, very slight

Clucking of the swell against boat boards.

Perfected vision: cockle minarets

Consigned down there with green-slicked bottle-glass,

Shell-debris and a reddened bud of sandstone.

Air and ocean known as antecedents

Of each other. In apposition with

Omnipresence, equilibrium, brim.

This is section xxiv of “Squarings” from Seeing Things (1991).

The shape and dynamics of the poem reflect what I call the metaxological narrative. Heaney uses the structure of the lyric, with the transitions between stanzas, to create a sense of ever deeper “seeing” into a mystery, that space we call the metaxy, where the It (Voegelin’s insightful term) moves through the living space of being things, giving the space dynamic unity open to transcendent otherness which remains mysterious. And yet this seeing is not apocalyptic, it is a loving response to a luminous gift of being in time. That is the ethical hallmark of the metaxological narrative: This moment of seeing the gift as gift, as gratuitous and asymmetrical to our powers. In a time when perhaps the majority of poets dally with some stripe of nihilism/apocalyptic, metaxological narrative nourishes a more modest attitude of gratitude and praise.

Which is not to say that the narrative is without tension. There are all those questions left unanswered, that longing to “know” suffering the temptation of what Desmond calls metaphysical anorexia. It would seem faith is called for at a certain point in the journey.

This point I call “metaxyturn,” which is the distinctive moment of the metaxological narrative. This narrative is shaped by a crisis, a turning point if not a conscious choice. Approaching the luminous space, the moment of the frustration of the senses becomes an opportunity: the mind, no longer adequate to its purpose, opens up to what is beyond it, and it is met with a compelling resourcefulness beyond its limits. The metaxy as space is shaped by a transcendent appeal. Because of his meditative mastery of the metaphysical steps of the ladder of finite being, this moment is reached without straining belief. Metaxyturn is a moment of grace; for the poet, a moment of the gift which finally animates and illuminates the dynamic tensional space carved out in our language by the poem.

Peering down through the harbor water, the poet observes many fascinating and beautiful things. A mix of human and natural things. Somehow the water is not only transparent but clarifying. The perceptions are acute: “very slight / Clucking . . .”

As the perceptions grow more insightful, they probe more deeply into geological time. Heaney’s use of the word “silence” suggests something of a meditative act of attention. Questions follow.

Then his responses hit a barrier, an obscure but scintillating question: which comes first? Air or water? The water evaporates into the sky, making clouds, and returns to the ocean as rain. An image of organic unity, cosmological yet inseparable from a generative wonder that is an index to the metaxological stance. So which came first? It’s like a Pre-Socratic riddle. The metaxy is the space within a generative, open whole of reality.

Which “thing” comes first? Impossible to say. And yet the poet finds a paradoxical expression that fits the occasion: “Air and ocean known as antecedents / Of each other.” “Known”: this is a human figure of speech by which the poet “knows” what he can’t prove by his senses. Ultimately the essay of the poem configures images of the origin without assertions or determinations. An infinite regress, much despised by some metaphysicians? Does the poet play fast and loose with the grammar of the metaxy? Or does the poem as a directional open whole reflect that aspect of the metaxy suggested by Voegelin in his last writing: the end of the quest for truth in the metaxy is not knowledge but faith.

This is to go beyond the poem. We return to the page.

The final phrase builds on the paradox: “In apposition with . . .” This identity is analogical: there’s an analogy between the riddle of firsts and the comprehensive vision given in the final line. Heaney calls with great finesse on one of the key issues in the tradition of the narrative, the question of the analogy of being. But in a sense he has subdued the metaphysical perplexity by the attention to the contingent: “theological” insights emerge from the contexts of the words, as if naturally. It’s a matter of poetic finesse.

The final line is mixed list of terms. Metaphysical: “omnipresence.” The second less abstract but still a term laden with complex relationships: “equilibrium” The third returns to the sense of “fullness” but as over-fulness: “brim.” We recall one of the original stories of the metaxological narrative: the birth of Eros from lack and plenty. Here is God’s plenty, the inexhaustible origin of beings let be.

As to the language, Heaney draws on “universals” or “perfectibles,” the grammar of which reaches outward into the unknown frontier of the language. Again, throughout his work and increasingly, Heaney seemed loyal to a vocabulary left in shreds in the age of suspicion, whose denizens had only to ask, “Who does he think he is?”

And, even worse/better: mystical? “Brim” is in a class of terms found frequently in mystical writings: words like overflowing, excess, bubbling over.

Reading a poem like this requires a concerted effort on the part of the reader. Eventually reading the poem becomes a meditative act: a sustained imaginative process of undergoing the narrative as a vertical path up/down through “perfected vision” of things in time into the heart of the metaxy. Heaney’s expression of this space, where elements relative to each other exist “in apposition with” hyperbolic universals like “omnipresence, equilibrium, brim,” is quite memorable. Connoisseurs of Voegelin’s metaxy will especially appreciate the several ways this poem manages to embody both the tension and the movement of the metaxy.

Also available are “A Late Poem by Wallace Stevens about the Metaxy,” “Czeslaw Milosz and the Metaxy,” “Geoffrey Hill and the Metaxy,” “Elizabeth Bishop and the Metaxy,” and “The Question of Literary Form.”