Geoffrey Hill and the Metaxy

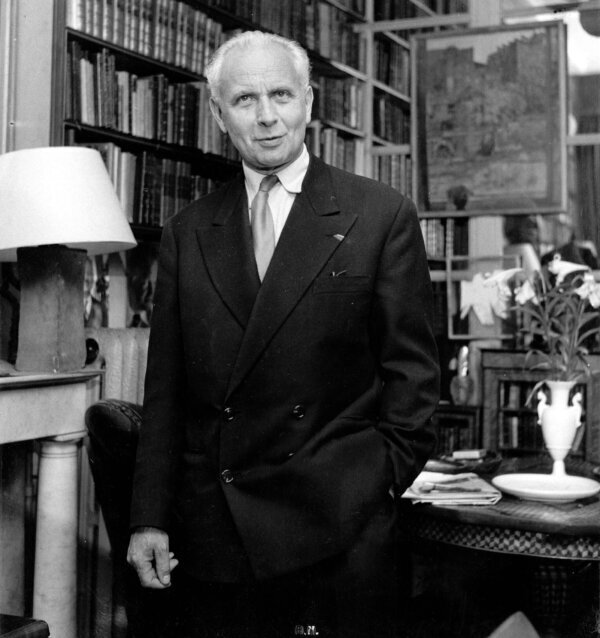

If I hadn’t been introduced to the metaxy by reading Voegelin in the 80s and William Desmond more recently I would have had to invent it to read the late British poet Geoffrey Hill (1932-2016). As a poetry reviewer I was often asked to review his books, and the poems were so dense with allusions and spiked with strong, anti-lyric feeling that they resisted my efforts to make sense of them along with the other stuff I reviewed. But I tried. An order emerged, slowly, and now I can see the patterns that became clearer at the volumes came out.

Hill’s reputation is as mixed as his poetic voices. Being the recipient of many prizes may have been cold comfort to him; his vision of poetry’s purpose had nothing to do with feeding false consolations to his public. Yet at this death, Hill was again acknowledged to be one of the great contemporary British poets; in life, his jacket copy rarely omitted hyperbolic blurbs such as this from A. N. Wilson: “Geoffrey Hill is probably the best writer alive, in verse or in prose.” But he was also by common acceptance unusually and perhaps perversely difficult. His theological interests alone made his poems rebarbative to many. The Bible, John Donne, Milton, Hopkins, Tyndale, Barth, St John of the Cross, Simone Weil, and so on: endlessly imbricated, acutely paraphrased, pointedly contrasted, these and hundreds of other sources flash intermittently in his wildly shifting styles. “Risen pilgrim, what’s ex cathedra this day? Daniel / into revelation; a great multitude / crying Hurt not the earth.” (The Orchards of Sion, XXV 2002). That sort of thing.

Essentially, Hill wedded two seemingly alien topics: a Biblical sense of original sin and a poet’s imaginative struggle with the unruliness of language, especially that of his contemporaries, in the search for truth. It’s as if he took personally the lack of fit between words and things. (That would be another essay but it is curious that the false model of symmetry promoted by Bacon should motivate some of his spleen not because it is false but because his experience failed to confirm it.) He castigated himself and others for semantic mishaps and culpable ignorance alike. He once agreed with Simone Weil that anyone discovering an error in a text – say an oversight by a copy-editor – should feel obliged to bring the case before a court of law. I know as a copy-editor/editor/publisher how, on seeing something I edited show errors once printed, I felt very very sinful.

Hill was both very serious – he is one of the great Anglophone poets of the Shoa – and seriously comical about his role in society. He claimed to have learned as much from popular standup comics as from great poets. Hill was ferocious about the debasement of the English language by politicians, poets, and talking heads. His anger became his hallmark and he relished his public image.

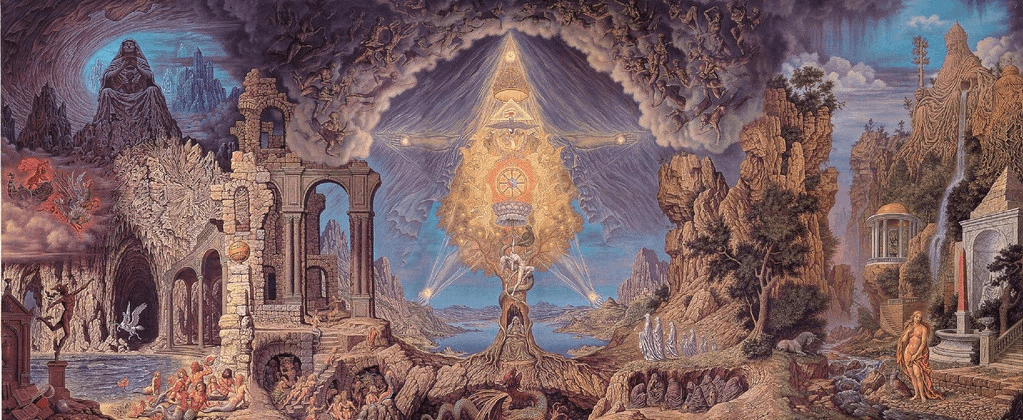

While a given metaxy may be situated among apocalyptic narratives – and Hill’s religious themes welcome this application – the metaxy I am following here is that of William Desmond. It is a philosophical narrative of being. With its origins in Plato, Desmond’s metaxy is a response to the devaluation of being in modern philosophy, particularly in Hegel. As O’Regan notes in a comment on Desmond’s style, while his constant returning to the voices of the tradition may recall Hegel, Desmond’s whole is not the parousia of meaning, the concept at home with itself, but a polyvocal spiral towards the mystery of agapeic being. The metaxological journey is a “selfing” by which the finite self finally encounters its nothingness (Hill would say its sinful nature) in light of the mystic God. Desmond writes: “There is no return of uncreated soul to uncreated origin; there is the opening to a communion of soul and origin, a communion ultimately a gift of the origin, since everything that is, though finite, is also such a grace.” (God and the Between, 273).

As we shall see, Hill’s poetic style likewise abuses the geometrical muse in favor of a time-out-of-time; in a sense of the word “Baroque” he would entertain, Hill is a modern Baroque poet. Desmond’s metaxy allows us to measure the always shifting distances of Hill’s poetic voice from the metaxical view in which “everything that is, though finite, is also such a grace.” In that “also” there’s shock and relief. Hill’s Barthian persona, raging at his isolation in a fallen culture and a fallen language, is open to that jolt of that truth but as poet he places it structurally so it doesn’t wrench the poem into apocalyptics. Which may be getting ahead of ourselves.

Hill’s fame is based on the memorability of his poetry. He is a great poet of memory in the practical sense – his acknowledgement of sources is deftly woven into the arguments of the poems; and in the personal sense – his vivid landscapes account for some of his most memorable passage. And in locating the “good place” in a fallen world, his memorial landscapes contributed to his idea of a “theology of language” – mentioned in a talk given in Toronto in 1998. As for grace, his theology of language focuses on discoveries made in the act of composition, often one would think in the act of revision; he calls such “abrupt, unlooked-for semantic recognition understood as corresponding to an act of mercy or grace” (Collected Critical Writings, 404).

Hill’s powers of lyrical description were considerable. Engaging the theme of prelapsarian existence, they provide heightened moments in some of his most distinguished poems. Here is XXIV from The Orchards of Sion:

Too many times I wake on the wrong

side of the sudden doors, as cloud-

smoke sets the dawn moon into rough eclipse,

though why in the world this light is not

revealed, even so, the paths plum-coloured,

slippery with bruised leaves; shrouded the clear

ponds below Kenwood; such recollection

no more absent from the sorrow-tread

than I from your phantom showings, Goldengrove.

I dreamed I had wakened before this

and not recognized the place, its forever

arbitrary boundaries re-sited,

re-circuited. In no time at all

there’s neither duration nor eternity.

Look! – crowning the little rise, that bush,

copper-gold, trembles like a bee swarm.

COLERIDGE’S living powers, and other

sacrednesses, whose asylum this was,

did not ordain the sun; but still it serves,

bringing on strongly now each flame-recognizance,

hermeneutics of autumn, time’s

continuities tearing us apart.

Make this do for a lifetime, I tell myself.

Rot we shall have for bearing either way.

This is part of a series of 122 poems each of 24 lines of loose iambic pentameter. In his later poetry (later in Hill first means the poetry written after his discovery in the 1990’s that the worst symptoms of his life-long problem of depression could yield SSRI’s – selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors), Hill’s muse is startlingly free wander stylistically – for example, as in the poem cited here, from memoir, to description, to tropic speech (addressing a name of a place in the poetry of Gerard Manly Hopkins), to idiomatic word-play (“in no time at all”), to Romantic apostrophe (“Look!”), to a reference, with typographical allusion, to Samuel Taylor Coleridge, whose idea of language as “living powers” Hill adopted into his more Barthian theology of sin, to the illusive metaxological “it”, and to a finish of high dudgeon. Such wandering from voice to voice is characteristic of the metaxical muse.

Negotiating these transitions is great fun once you get the hang of it, but it takes practice. Getting the hang sends the contemporary reader to many source books; and there’s no end to that. That said, the metaxological narrative developed by William Desmond allows one to participate in the ongoing mediations of the poem’s structure in time. In the commentary below, I will mark off the sections of the poem in terms of the voices of being as given by William Desmond: the univocal, the equivocal, the dialectical, and the agapeic or metaxological.

The opening is univocal: “too many times” something happens. Something that happens repeatedly is not to be doubted. But almost immediately the univocal voice unfolds in the broader voice of the equivocal: “cloud-smoke sets the dawn moon into rough eclipse, / though why in the world this light is not revealed . . .” The language of revelation, given the equivocal circumstance, rings like a strange bell; that bell echoes in the apostrophe “such recollection / no more absent from the sorrow-tread / than I from your phantom showings, Goldengrove.” Goldengrove recalls Gerard Manly Hopkin’s image of prelaptsarian innocence. Yet Goldengrove is an active agent in Hill’s imagination.

As the poem proceeds it thickens. The apostrophe involves a comparison that brings into ratio two contrasting forms of experience, the personal and the revelatory; but then who argues now that these are contrastive, the latter being eclipsed in popular culture like the dawn moon in the poem? But for Hill, all of these forms of experience happen “metaxologically” in the space of experience between the univocal and the agapeic. The univocal gives way to the equivocal, the equivocal to the dialectical; the metaxological completes the narrative. Since the voices are not conceptually watertight, but rather porous to the other, rude awakenings happen at any point. Here “showings” means appearances, as of an illusion, but the equivocal nature of the word allows Hill to transition to the word meaning “vision” as in Julian of Norwich’s compendious meditation of communications from God on her deathbed (which turned out to be not her deathbed).

In the metaxy, time is double; time is linear and time is porous. Hill is scrupulous about finding the grammatical means to represent the various intersections of various senses of time. Here: “I dreamed I had wakened before this” sets a foreground/background situation; and within that dream of waking he did NOT recognize the place (we hear echoes of Eliot’s Four Quartets, and Eliot was always one of Hill’s great others). This is followed by another fusion of idiom: “In no time at all / there’s neither duration nor eternity.” Finding the middle term between opposites requires a play on words, and “in no time” fills the bill. The idiom saves the univocal distinction between duration and eternity from platitude with the equivocation of “in no time at all.” Meaning “suddenly” but more than suddenly, even faster than that; as if he had penetrated to an always already-there dimension of sacred time.

And now, to illustrate such a suggestion, we have a Romantic-style vision of nature: “crowning the little rise, that bush,/ copper-gold, trembles like a bee-swarm.” But our lingering over this delicious passage is rudely interrupted, at least until we “get it,” by the next sentence, a reference to Coleridge’s concept of words as “living powers” as opposed to inert units of mind-stuff. Coleridge is one of Hill’s great deads, and often features in Hill’s critical writing when he rehearses the controversies over semantics engaged by Bacon, Hobbes, and other materialists. Here his “dream vision” supplies an “asylum” for the ideas of Coleridge and “other sacrednesses.” The awkwardness of that word should qualify the tone of the phrase; as we noted, Hill is given to comic renderings of heavy points. That said, such living powers did NOT “ordain the sun.” Words are not things.

Hill was no obscurantist and he carefully allowed for dimensions of thought that amplified his experience without distorting his prickly documentation of contemporary thought—“time’s continuities tearing us apart.”

In Desmond’s narrative, the dialectical gives way to the metaxical. This striking phrase – “time’s continuities tearing us apart”—vividly suggests the abyss of the dialectical voice. For Desmond, the exhaustion by dialectic of the independent autonomous searching self creates a crisis, or a moment of grace. The autonomous self is finally empty, staring into an abyss. At this point the “reserve” of agapeic being, as in the origin of creation, may pour into the space of the metaxy from being’s excess.

Tension is the hallmark of the metaxy. The four voices of being do not render each other moot; depending on the sequence, they qualify each other, as do Hill’s dreams and his waking convictions. The presence of spiritual places—like Goldengrove, the name he remembers from Hopkins’ poem “Spring and Fall” – is deeply embedded in Hill’s imagination and memory as revealed in recurring early morning dreams. Yet such is Hill’s craft that his prelapsarian images of a lost time before “the terrible aboriginal calamity” (Newman) alternatively convey the philosophical truth of the metaxical search.

Given the open whole of metaxical space, and the narrative that orients it to the beyond, Hill’s imaginary illustrates what Desmond calls the “contingency of happening.” Desmond writes that such contingency “is not just relative to other finite beings but inherent in the very being there of this being, indeed of all thises, of all finite happening. It is but it might not be; it might be otherwise, and it will not be, when its mortal term expires. And not just nothing at the conclusion of its mortal span: nothing at the beginning, middle, and end. That it might not be at all—nothing present at its origin. That it might now be other than it is – nothing present in its between. That it will not be—nothing present at its end. There is a nothingness that enters the ‘that it is at all,’ and this is not a relative nothing marking a finite process of determinate becoming, for the whole of the process is streaked with this nothingness. And, likewise, the process of the whole” (God and the Between, 250).

Hill experienced “contingency” in his wide dialectical search through the spaces opened up to him as a modern Christian, even post-Christian, poet. He remained true to the doctrine of original sin, but for him that truth also abided in the tensions inherent in the possibilities of grace. When he discovered that the terrible episodes of depression he’d known from childhood could be treated by SSRI’s, he understood it as an event of “grace” or “mercy”; and the resultant torrential creativity that now visited him was part of that event. Such experiences of being are not to be denied. We must make them “do for a lifetime.”

Such showings, as offered, are ours to honor. One of Hill’s recurrent themes is the dead and they honor we owe them. Much of his richest imagery comes from accounts of the extreme violence and suffering undergone during the world wars. But the dead extend backward into the reaches of historical time.

The final line of the poem – “Rot we shall have for bearing either way” – displays Hill’s wordplay at its most effective. Echoing Shakespeare’s sense of “rot,” the line expands in several directions thanks to Hill’s exploitation of a range of meanings of “bearing.” One of Hill’s great topics in his critical prose, and it is reflected in his poems, is etymology. His own project of a “theology of language” starts with his habitual use of the Oxford English Dictionary. Hill’s sense of words included their etymology and their many historical usages. The earliest “meanings,” as given in the etymology, could be treated as sacred, as original, even prelapsarian: this is a fiction of course and Hill’s use of “etymology” included the various contexts cited in the OED and he often deployed several usages at the same time. “Rot we shall have for bearing either way.” That is, either way “time’s continuities” tear us apart, all ends in “rot”: and rot we have for bearing. We take our bearings not by the pure use of words – there is no such thing – but on the sense of a words intermediation of human experience, with different accents and pitches depending on the context. In this context, an even richer wordplay could be defended: for bearing and forbearing. The rotten state of the language, of a given words usage, can orient us, but only if we can feel the depth of the rot. And the unavoidable contingency of rot exercises our forebearance lest we lose the capacity to “Look!” and see that copper-gold bush on the hill.

This complicated state of affairs – both densely realistic and superbly aware of what is at risk in the imagination – is Hill’s metaxy. At the end of this poem, the “agapeic” voice predominates but not univocally: it is always, for Hill, a matter of pitch, what Desmond could call “finesse.”

Hill’s lifelong wrestle with the meanings of words was in service of what he believed were ancient, perhaps primordial values. Our visionary experiences that expand our awareness of life’s complexities do not “ordain the sun.” There is an otherness to the source of light that has traditionally been accepted as a non-thing thing outside human experience. Each poem of the metaxy is a re-siting (and also reciting) and re-circuiting of places and their “forever / arbitrary boundaries.” Note how he used the line-ending to exploit the equivocal tension of “forever” and “arbitrary.”

His poems at their best are scrupulous renderings of the selfing quest in the metaxy. They are difficult because it is easy to misrepresent this quest, human language being what it is. And yet the reader of Hill’s work may be forgiven if pausing to consider the scales of justice and grace, he notes the inappropriateness of the figure, since grace is pre-eminent. Indeed, the polyvocal texture of the whole creates, as we attend the poems mindfully, a sense not of Dante’s Hell but at least of the mountain of purgatory with glimpses of heaven.

Also available are “Seamus Heaney and the Metaxological Narrative,” “A Late Poem by Wallace Stevens about the Metaxy,” “Czeslaw Milosz and the Metaxy,” “Elizabeth Bishop and the Metaxy,” and “The Question of Literary Form.”