Social Psychologists’ Attack on Intuition and Expertise

Iain McGilchrist comments in The Matter With Things that our moral intuitions often cannot survive extremely fanciful hypothetical situations nor imagining counterfactual imputations of omniscience. Our intuitions of all types have evolved for naturalistic situations. Such things can never be one hundred percent accurate, but we would not be here if our ancestors could not rely upon them more often than not. Edward Dutton’s book How to Judge People By What They Look Like shows that physiognomy, for instance, is a reasonably reliable indicator of somebody’s character and intelligence. We sometimes have a split second to decide whether to trust someone or not. McGilchrist notes that we make a judgment about trustworthiness, competence, aggressiveness and likeability within a tenth of a second.[1] This opinion does not change much upon further experience. Women, being generally physically weaker, smaller, and more vulnerable, are more skeptical about trustworthiness than men, on average.

The British like to hire actors and actresses that belong to the social classes they portray on TV or films. One actor on “Shetland” was hired to play a social misfit and lowlife who had been falsely accused of murder, it turned out. He had returned to his community of origin after his conviction was quashed, but the locals still suspected he was guilty. He gets variously beaten up and generally persecuted. And what a miserable specimen of humanity the actor was. He then turned up to depict a violent psychopath on “Silent Witness,” correctly convicted this time, but who was in danger of being released from prison on a technicality unless the pathologists and police can come up with new evidence. How awful to be this actor. He is typecast for a reason. Sometimes these actors’ face, body, and accent make it almost impossible to believe he is not the most awful miscreant to be given the widest possible berth. It would be amusing to discover that the BBC does casting calls at the local prison.

While this might seem like evidence that we should not trust our ability to judge people by what they look like, the canny casting directors are relying on the veracity of our intuitions to confirm the appropriateness of their casting choices. If the audience members all had unreliable intuitions, we would all have different reactions to these people. But we do not because evolution has honed this ability.

McGilchrist points out that psychologists love to find ways of tricking and defeating our intuitions in an effort to prove them unreliable. Daniel Kahneman’s Thinking Fast and Slow comes under criticism for doing this. Thinking fast for Kahneman, a social psychologist, denotes intuition, and the slow part, rational analysis. Because intuitive insight is so fast it can seem that it involves prejudice; some kind of illegitimate hack, but this is not the case. Schizophrenics can lose their theory of mind (ability to estimate the emotions and thoughts of others) and must instead attempt a conscious analysis, with typically poor results. This “thinking slow” does not work well at all and is distinctly inferior to intuition. One personal example is the ability to tell whether an actor is really playing the violin or not. It is possible tell with near certainty within two seconds. A negative judgment, in particular, is basically infallible. This is if the observer grew up playing the violin and has years of experience. A long-time smoker can tell if an actor is faking being an experienced smoker, again, particularly in the negative. Someone with long experience of soccer can spot someone pretending to be an expert soccer player in an instant too. Conscious executive functioning has nothing to do with intuitive assessment. In fact, it is impossible to verbalize. At most, one can simply assert, “You’re not doing it right!” There is no way my wife can teach me how to recognize fake smokers and I could never explain how to recognize that someone is not really playing the violin. It would not be possible to write a book about it, and if it were, it would be no more possible to acquire the requisite ability than reading a book about how to play soccer makes one a good footballer. Or even a better footballer unless the skills are actually practiced. These examples of know-how cannot be taught verbally. Violin-playing, smoking, and playing soccer, have no linguistic component. Skill is acquired through practice. When looking at others the observer does something like feeling it with their bodies. Someone with the ability cannot explain how he does what he does. In fact, this is the case with all expertise. A doctor who is an expert diagnostician is relying on years of experience, similar cases, and things that make this case distinctive. This cannot be summed up in words. An expert radiologist relies primarily on a Gestalt impression of the x-ray and the non-verbal right hemisphere deals with Gestalts. One very expert doctor, who McGilchrist describes, would make his hospital rounds daily, apparently socializing, chatting with his patients. What he was actually doing was looking for any tell-tale changes in the faces of his patients as to whether they were improving or getting worse. Using this method, he could identify problems two to three days before the more junior doctors helping him. He would not be able to verbalize this skill either. A sensitive philosopher knows that “if God did not exist it would be necessary to invent him.” This is intuitively obvious as a matter of basic philosophical insight. Explaining it or defending this claim is secondary. It should really not be necessary. Yet, part of the game of philosophy involves trying to. If someone does not see why it would be necessary to invent God, an argument could conceivably do some good. But, if someone positively disagrees, then it is almost certain that an argument will not convince him. The notion features prominently in Dostoevsky’s The Brothers Karamazov in a speech by Ivan in a prelude to The Grand Inquisitor parable.

McGilchrist quotes approvingly Why Do Humans Reason? by Hugo Mercier and Dan Sperber. The authors point out that reasoning is seen as improving knowledge and making better decisions, but that actually, its main function is argumentative. Arguments are necessary when people are unwilling to take what is said on trust. This occurs more commonly in large societies where people do not know each other. Mercier and Sperber write that “the evidence is that reasoning leads to epistemic distortions and poor decisions. Reasoning pushes people towards decisions that are easier to justify, not the best decisions.”[2] The desire to improve school-based education has led to attempts to quantify and test educational attainment – an example of our currently beloved “scientific” attempts to reason. That means that all that cannot be quantified is ignored and the teacher teaches for the test. Literacy and numeracy have measurably declined as a result, ironically enough. The fact that the best teachers love their subject, are enthusiasts, and thus can inspire their students with a similar love through mimesis, is not quantifiable. “Hey, Jeff, this student’s love for geography has increased 34% after a six-month exposure to Mr. Wilson.” When applied to intuitive insights, reasoning is largely about rationalizing insights, not correcting them. Reasoning is the potential source of new errors. Jonas Salk, the inventor of the polio vaccine, argued that one should start with intuition, subject it to [LH] scrutiny and reason if necessary, and then send it back to [RH] intuition to be assessed again. Intuition needs to be the final arbiter.[3] It is true that how confident a person is in his intuition means nothing, as found by Leach and Weick, 2018.[4] It is possible to be very good at intuitive thinking while thinking you are bad. This got misreported as suggesting that there is something wrong with intuition and that it does not help us make better decisions. In a radio interview, Weick commented that “Overall, actually, our intuitions are quite good.”[5]

McGilchrist spends several pages discussing the case of a horse trainer whose job became to estimate which horse would win the race.[6] He would spend two minutes assessing the horses before a race that quite typically is won by just one-tenth of a second. He would then phone in his assessment of their relative likely placements in the forthcoming race to a syndicate of betters. His results were excellent; very consistently beating the odds. However, he was immensely troubled by his inability to explain how he did it, though he has this in common with any expert. He would often second-guess himself and phone the syndicate again, telling them to bet less. These phone calls were so counterproductive, costing the syndicate money they would otherwise have made, that the people who actually put the money on the horses told him never to call once he had made his prediction. His intuitive predictions were only made worse by his skepticism. Here was an instance of someone being very unconfident about his intuition while actually being very good at it.

McGilchrist describes following up Kahneman’s evidence for his claims that experts are unreliable.[7] It turns out that it is Kahneman who is unreliable, not the experts. The experts examined include doctors, auditors, pathologists, and radiologists. When McGilchrist read the relevant articles cited by Kahneman, he found that they said the opposite of what Kahneman claimed. Kahneman asserts that the study about the radiologists was about interpreting chest X-rays. Actually, neither chests nor X-rays were involved. The area was gastroenterology! Kahneman even invents the idea that the experts contradict themselves when shown the same data ten minutes later. That idea is never mentioned in any of the studies he cites. In order for the test to mean much, the radiological results would have to have a clearly “correct” answer and they did not. The six factors the radiologists were asked to evaluate were abnormal, but whether they indicated cancer or not was dependent on context, which was not supplied. The whole thing was highly artificial with “yes/no” answers on a sheet of paper. Real clinical judgments concern specific patients. The same symptoms can mean very different things that an intuitive evaluation of an actual patient can disambiguate.

Additionally, of the nine radiologists, three were not experts and were not even fully qualified. The status of the other six is not known, but it has been pointed out that real experts are usually too busy to participate in surveys and studies. Despite all this, the radiologists were “right” 80% of the time. However, one could argue quite sensibly that drawing firm conclusions about all radiologists based on just nine people seems unreasonable. The single study Kahneman uses to debunk the expertise of radiologists can be found in this footnote.[8]

With regard to the auditors, there were 288 questions of judgment with words like “satisfy,” “adequate,” etc. Such vague language rules out extreme precision. Yet, there were the same bald yes/no answers required. Nonetheless, the auditors, who had between three- and seven-years’ experience, had a high degree of judgment stability at 0.79, which is apparently consistent with the general positive conclusion of auditor judgment studies. Kahneman, however, reframes this as a 20% contradiction rate.

The third paper Kahneman examines was by James Shanteau. According to Kahneman, this was supposed to be a review of 41 separate studies about experts including auditors, pathologists, psychologists, and organizational managers. In fact, there were 46 studies. Of the 46, only 9 were critical of experts. 37 were neutral or supportive.[9] Shanteau himself had started out with a bias against the idea of expertise. To his surprise, he found that experts truly were careful, skilled, and knowledgeable. Hence, it is odd, and even unfathomable, that Kahneman should choose Shanteau’s review to back up his skepticism. “Expert systems,” however, are another matter. They are an attempt to externalize intuitive processes and they are not much good at all unless the data is very clear and unambiguous, in which case, expertise is not even needed.

McGilchrist ends his discussion of Kahneman by pointing out that Kahneman’s parting shot is to say “unreliable judgments can’t be valid predictors.”[10] However, experts are not making predictions. Expertise involves assessment or diagnosis. In fact, when it comes to prediction, McGilchrist quotes Niels Bohr saying “we can’t live life without making predictions, but we should do as little as possible.” And Whitehead, who suggested that “the track record of professed seers was so poor that . . . it would perhaps be safer to stone them in some merciful way.” Much of Nassim Taleb’s masterpiece Antifragile reiterates this point and rails against the phoney attempts to predict the market that underestimate the likelihood of rare events, which, by their nature, cannot have large amounts of data compiled about them. When we read about seers and soothsayers in Homer’s epics, we are apt to regard the Bronze Age Greeks as gullible dupes, and yet we display the same degree of credulity with talking head prognosticators on TV.

Anything we do not elaborately ponder will count as “thinking fast” under Kahneman’s terms. And we do not elaborately ponder much. We have neither the time nor the energy to do so. Whitehead wrote about intensive thinking as something short lived and draining, so it needs to be undertaken judiciously. “It is a profoundly erroneous truism, repeated by all copybooks and by eminent people when they are making speeches, that we should cultivate the habit of thinking of what we are doing. The precise opposite is the case. Civilization advances by extending the number of important operations which we can perform without thinking about them. Operations of thought are like cavalry charges in a battle — they are strictly limited in number, they require fresh horses, and must only be made at decisive moments.”[11]

There is no question that expertise exists. There are expert chess players who can demonstrate their skills by beating you; or even fifty people at once. They can easily memorize “meaningful” positions on a chessboard, but not when the pieces are arranged haphazardly. Expert contractors can construct things that are attractive and sturdy. Expert composers often have just a few days to compose the soundtrack for a film. Those in the prediction game, however, estimating the outcome of elections, or how the economy will perform, are charlatans and frauds who Taleb would like to run out of town. A quick look at their track record is all that is needed to confirm this, whereas medical diagnosis, though inexact, is not just one hellscape of dead bodies whose symptoms were misunderstood. Expertise is needed where the symptoms are ambiguous and common to multiple diseases. Perfection will be impossible for such complicated cases, but ten years’ experience will be better than one if you have a smart and sensitive doctor.

The fact that Kahneman is off base with his ideas concerning “thinking fast and slow” is also suggested by his answer to a question put to him by Sam Harris on Harris’ podcast “Making Sense With Sam Harris.”[12] Harris is an example of how rationalism can be quite irrational. While speaking in a seemingly calm and measured manner, his case of Trump Derangement Syndrome has become infamous. Supposedly devoted to the truth, Harris was happy for all major newspapers to lie and engage in propaganda to try to stop Trump getting elected or reelected. This was supposed to be worth losing any remaining faith or trust the general public might have had in its main source of news. Harris regards Trump University as about the worst thing any American politician has been associated with, apparently not being familiar with the sorry state of American education in general. Trump gets paid for lending his name to various projects that he does not manage. Whether they succeed or fail is not his problem, which does not seem great, but also not Armageddon. When asked about Hunter Biden’s laptop possibly implicating Joe Biden in a massive kickback scandal, Harris replied that were Hunter Biden’s basement to be filled with the dead bodies of children this would be irrelevant compared to the awfulness of Trump University. Just what were they doing at Trump University? Murdered children versus a rip-off education? Students are routinely left with worthless degrees in phoney subjects everywhere. Does Harris know that college administration is siphoning money from students right into the bank accounts of do-nothings and know-nothings of the failed academics with titles like, Chief Diversity Officer, or Assistant Provost for Interdepartmental Technology and the Committee on Investor Communications?[13] Harris has even written a book about the importance of not lying. From the Amazon blurb for the book, Lying: “Most forms of private vice and public evil are kindled and sustained by lies. Acts of adultery and other personal betrayals, financial fraud, government corruption – even murder and genocide – generally require an additional moral defect: a willingness to lie.”

The Hunter Biden laptop story was reported in The New York Post which promptly got vilified by the liberal press and banned on Twitter for reporting it. The story could not even be communicated by direct message. Twitter “locked the account of then-White House spokeswoman Kayleigh McEnany because she tweeted the story.”[14] (The same thing happens on Facebook if anyone tries to include a URL to The Orthosphere blog either in a post or on Messenger). Conforming to Harris’ desire and willingness to lie for political expediency, fifty senior intelligence officers signed a statement claiming the laptop story “had all the hallmarks” of Russian disinformation shortly before the 2020 election. This was not true. It should not be too much to ask to have those people lose their jobs, and certainly never to be consulted or taken seriously ever again.

Harris seemed thrilled to interview Kahneman who Harris imagined was a fellow rationalist. At the end of the interview, Harris asked Kahneman whether, after studying “thinking slow,” and the various errors we humans are prone to, for decades, whether Kahneman was any more rational than he used to be or any less prone to those errors, Kahneman answered emphatically in the negative. Unable to believe his ears, Harris asked him again, and again, Kahneman said no. There are two lessons to derive from this. One, is that if researching and writing Thinking Fast and Slow had no benefit for the author, it will be unlikely to benefit the mere reader. The second is more speculative, but supported by McGilchrist’s tracking down of Kahneman’s sources, that Kahneman is simply on the wrong track. “Thinking fast” is based on intuitive assessments. Some of these are the products of evolution and are quite adequate for their purpose. And the other species of thinking fast, as opposed to laborious explicit chains of reasoning, is skilled expertise. Expertise, in certain fields, is quite real, notwithstanding Kahneman’s mischaracterization of the evidence.

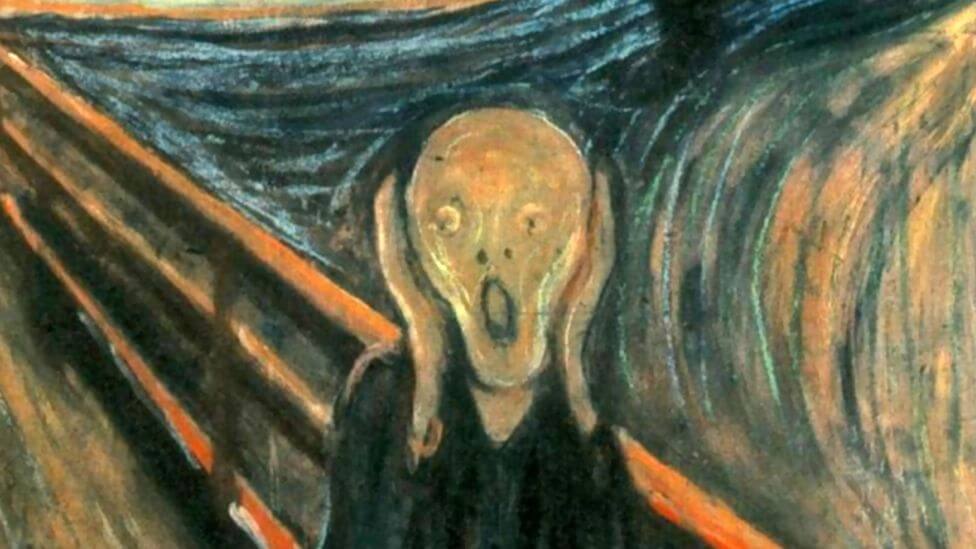

Intuitions and LH skills must be reasonably reliable precisely because we are forced to rely on them for the majority of cases. If they were not, we would die out. The cottage industry of social psychologists finding ways to defeat our intuitions should not lead us to become generally skeptical of intuition. McGilchrist comments that it is perfectly possible to fool our senses. There is a picture involving shadows and a checkerboard where two squares seem to be different colors but they are in fact the same. Since one square is depicted as lying in shadow, our minds, in a very sophisticated manner, compensate for that. The picture exploits this ability to “fool” us. One could argue back that were the checkerboard to exist in real life, the judgment based on our perception would be correct, and mistakes in real life are more consequential than pictures. But, the checkerboard is only a drawing, so we are, in fact, wrong. However, the fact that our senses sometimes can be deceived (here we have overtones of Descartes’ First Meditation in Meditations on First Philosophy) does not mean we should disregard what our eyes tell us from now on. And, the same goes with moral intuitions. Descartes only made his comment that one should never trust what has deceived you even once in the context of a quest for certainty. Whole books have been written on the perniciousness of that aim. Most of life contains no such thing.

In Realism Is Needed For Moral Intuitions to Function Properly it is claimed that very unrealistic hypothetical situations like the one described in the trolley problem make moral intuitions seem much more unreliable than they truly are, as pointed out by Iain McGilchrist. Intuitions evolve/arise in the context of real-life situations. The trolley problem has the nature of artificial classroom exercises designed to make some logical point or other. Those exercises typically require a suspension of disbelief and a bracketing out of practical matters. For instance, the problem to be discussed might start out, “You are told by a close friend… .” An obstreperous and annoying student who is failing to get the point of what is going on might ask, “Which close friend?” “How did they tell me? Was it face to face, by text, what?” Oral culture individuals are like this and tend to remain in the concrete, unwilling to enter into abstractions. When given the syllogism: “There are no camels in Germany. Dresden is in Germany. Are there any camels in Dresden?” They will say, “I don’t know. I’ve never been to Germany.” “How do I know there are no camels in Germany? Just because you told me? I don’t know you or whether to trust you.” The literate student understands that the truth about the absence of camels is not the point which is that, logically, what applies to Germany in this case must apply to Dresden.

Literate people with years of exposure to hypotheticals designed to teach some point or other would wonder why the oral culture person is being so uncooperative. Doesn’t he understand the Venn Diagram of Dresden being within Germany? The trolley problem is just like the camels in Germany question, but moral intuitions function reliably only with Aristotle’s concrete situations with specific individuals and not with classroom hypotheticals. The trolley problem assumes we know all sorts of things in advance that we would not know, specifically, the actual outcomes of all our actions. The assumption of this kind of omniscience is so far from reality that we end up flailing. We have absolutely no idea what human existence would be like if we were omniscient. We would know all the possible courses of action available to ourselves and all other eight billion people on the planet. We would know what would happen if an infinite number of choices are made and what will happen if those choices are not made and other choices are made instead. You would know how to thwart all my plans of action and I would know how to thwart your attempts to thwart me and you would know how to thwart my attempts to thwart your attempts to thwart me ad infinitum. It would be as though we all became infinitely strong supermen but who are in competition with other infinitely strong supermen canceling each other out.

With the ability to see into the future it would seem a bit pointless to get up off the couch. There would be no books to read, films to watch, poetry to write, conversations to be had. You know the contents of every book, every detail of every film ever made or yet to be made. You can recite every poem that both has been written and ever will be written, and all the poems that never will be written. Every conversation has, in effect, already been had. So, no one will bother talking to anyone else. What would be the point?

Henri Bergson writes, somewhat gnomically, that possibilities do not exist even as potentialities before they are realized, which could be read as a counter to the possibility of omniscience. At one point in technological development, CD-ROM based video games existed. On the CD-ROM was every possible move that could be made in the game. Omniscience would seem to require such a scenario. Bergson writes: “[Philosophers] seem to have no idea whatever of a [free] act which might be entirely new (at least inwardly) and in which in no way would exist, not even in the form of the purely possible, prior to its realization.” “In duration, considered as a creative evolution, there is perpetual creation of possibility and not only of reality.”[15] Once, say, a work of art is created, this itself creates new possibilities and potentialities for later creation. The personalization of possibility seems suggested by the existence of artistic, musical, and maybe even scientific genius.

The CD-ROM picture of reality is a dead, block universe where different paths are mechanically followed with predictable results. Actual creation, whether by God or Man, requires freedom, a collaboration with Emptiness or the Ungrund where the possibilities are themselves created in conjunction with the interests, tastes, personality and experience of the artist, scientist, philosopher, etc. My possibilities are not your possibilities and vice versa. Omniscience, again, whether of God or Man, rules out creativity and novelty and renders everything pointless and boring.

If the moral decision maker is now omniscient, maybe he could ensure that the imaginary scenario never takes place in the first place. No wonder poor undergraduates, and everyone else, are befuddled and confused and their moral intuitions prove to be inadequate for dealing with these impossible fictions.