Socrates’ Homer in the Republic: Retaining the Poetic Past and Preparing for the Philosophic Future

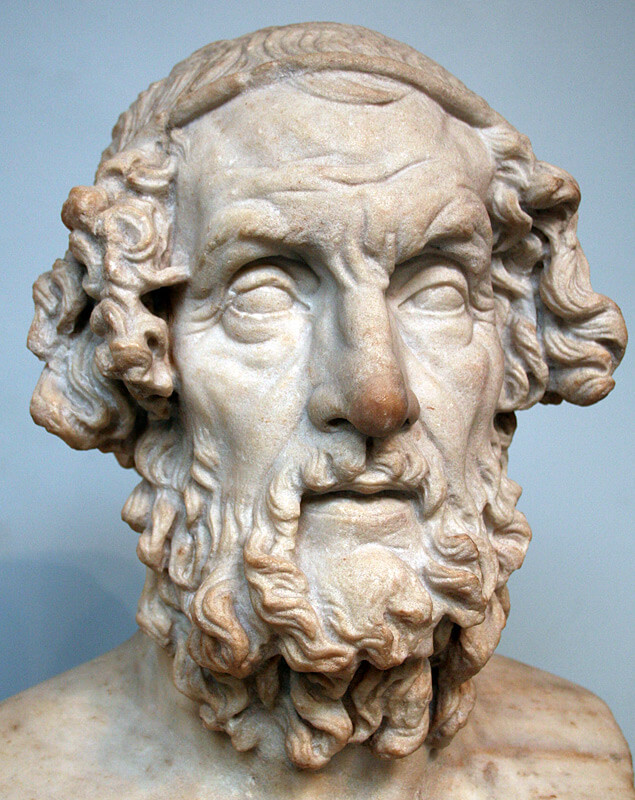

Homer is acknowledged by Socrates as the educator of Hellas, “the most poetic of the poets and the first of tragedians” who provides the model around which the Hellenes order their lives (Rep 607a).[1] The first references to Homer in the Republic confirm the poet’s commanding civilizational influence on the Hellenes when both Socrates and Adeimantus speak of Homer in the context of what people have learned from him. In his refutation of Polemarchu’s definition of justice, “helping your friends, harming your enemies,” Socrates points out that this definition of justice makes a just man a kind of thief, something which Polemarchus must have learned from the Odyssey where Homer admires Odysseus’ grandfather, Autolycus, for excelling all men “in thievery and perjury” (Rep 334a-b; Odyssey 19: 395-96).

Polemarchus is not to be blamed for this misconception of justice, for, as Adeimantus recounts, the poets teach the Hellenes that justice is praised only for its beneficial consequences. Adeimantus cites the Odyssey as evidence of this teaching:

Even as when a good king who rules in a god-fearing way,

Upholds justice, and the black earth produces

Wheat and barley, and his trees are laden with fruit

His flock increases and the sea teems with fish

(Rep 363b-c; Odyssey 19.109-13).

People should be just for the rewards and reputations it brings and not for its own sake – the challenge that Glaucon and Adeimantus propose to Socrates to prove.

Socrates’ proof that one should be just for its own sake is contrary to what Homer teaches. For instance, Homer shows the gods granting misfortune and evil to just people and their opposites a contrary life and mendicant priests and soothsayers swindling the rich with their claims that they can expiate their family’s misdeeds and harm their enemies with spells and enhancements (364b-c). These things are all possible because, as Homer states, the gods can be easily manipulated:

The gods themselves may be swayed with sacrificial

Feasts and soft prayers, libations and incense

When men have gone too far and done wrong

(Rep 364d-e; Iliad 9.497-501).

Thus, Homer teaches the Hellenes that a person should be just not for its own sake but for the rewards it brings; a just person can suffer from misfortune while an unjust one can be blessed; and the gods, the dead, and the living can be influenced by magic, sacrifices, and prayers. As Glaucon’s story of Gyges ring illustrates (Rep 359d-360b), and as Adeimantus highlights, the “main point” is for Socrates to show why the just life is worthy for its own sake and superior to a life where one “seems”” just while actually living unjustly (Rep 362d-363a).

Socrates’ challenge is immense, as Homer appears to teach the Hellenes exactly the opposite: one should seem to be just to reap the rewards that a just reputation brings but in fact live an unjust life for the benefits that such a life offers. With the Hellenes raised in these values, what stratagem, Adeimantus asks Socrates, could be devised “to persuade a man with birth, wealth, or strength of body or soul that he ought to respect justice and not snicker at the very word?” (Rep 366c). For Homer’s influence on the Hellenes is more than cultural, social, or political: it is foundational.[2] Homer’s poetry is the mythical, cultural, and existential fabric that make the Hellenes a people.[3] Without these stories, there are no Hellenes. Given this, how can Socratic philosophy succeed in showing the just life is superior to the unjust one?

This “ancient quarrel between philosophy and poetry” seems to place an insurmountable burden on philosophy to prove its preeminence over poetry (Rep 607b).[4] One option for Socrates is to eradicate Homeric poetry completely in the civic education of the guardians and leave only philosophy.[5] However, such a strategy would not only deprive the Hellenes the civilizational fabric that makes them a people, but it also may not be effective in civic education, especially in the teaching of children who are not entirely receptive to reason.[6] Another approach is to leave Homeric poetry alone and prepare only a few for philosophy: philosophers would provide lip-service to the public about their beliefs in Homeric teaching while in private pursue a life of reason.[7] A final possibility is to create a rival myth that combines philosophy and poetry together in order to supplant Homer’s place as the educator of all Hellas.[8] Socrates’ Myth of Er in Book X, and the dialogue the Republic itself, would be the types of philosophical myths that re-found the Hellenes as a people with a new set of values and way of life.

In this article I argue that Socrates seeks to rehabilitate Homeric poetry as much as philosophy will permit by his selecting those passages that support his philosophical aims and censoring or modifying those excerpts that are contrary to it.[9] Instead of repudiating Homer’s poetry altogether, Socrates recognizes that the foundational role his stories have for the Hellenes and therefore knows that they cannot be eradicated entirely; otherwise, they would not exist as a people. Philosophy consequently must accommodate Homer’s poetry but only under its supervision in order for citizens to become just. By retaining the passages of Homer’s poetry that are compatible with his philosophy, Socrates is able the preserve the foundational role that Homer plays for the Hellenes, while, at the same time, prepare them for a more philosophic future.

This reading of the Republic is compatible with previous scholarship on this question: Socrates does eliminate Homer’s poetry from the city but not all of his poetry; Socrates expects only a few to be able to study philosophy but leaves poetry for the many; and Socrates’ own poetry, like the myth of Er and the Republic itself, are a new type of philosophical myths but still anchored in the foundational fabric of Homer’s poetry. According to this reading, Socrates is neither a philosophical radical nor a political revolutionist but a pragmatic reformer who works within the cultural milieu of his civilization to make it more receptive to a life of philosophy. Although he had failed in his own time, Socrates’ attempt provides a blueprint for us today as we wrestle with the questions like national identity and civic education in our own country.[10]

I

Socrates’ first criticism of the poets, including Homer, is they make false claims about the gods, spirits, heroes, the dead, and just people. When discussing the education of the guardians, Socrates condemns the stories that Homer tell – “false stories which are told and still being told” – because they misrepresent the nature of the gods and heroes (Rep 377d-e). Stories like Uranus, Zenus, and Cronus chaining and castrating each other and swallowing their children or those of “Hera enchained by her son and Hephaestus hurled by his father out of Olympus for trying to defend his mother, and the battle of the gods that Homer tell” will not be permitted in Socrates’ polis (Rep 377e, 378d-e; Iliad 1.586-94).[11] These stories need to be censored because they will permanently damage the character of the young, who are easily impressionable and vulnerable to “any stamp one wishes to put on them” (Rep 377b).

Socrates’ first law for religious speech and writing therefore is that the god is the cause only of good (Rep 380c; 379c). Socrates does not tolerate the poets’ error that the gods are responsible for both good and evil, as Homer states:

Two jars of lots stand in Zeus’ hall

One of good, the other of evil

And to whomever Zeus gives a mixed portion, he “falls now into good, now into evil,” while one who receives unmixed evil is “driven by misery over the entire earth.” (Rep 379c; Iliad 24.257-32). Socrates also suppresses the Homeric lines that call Zeus “a dispenser alike of good and evil to mortals”; when the gods goad the Trojan hero, Pandarus, to violate his oath that could have potentially have led to the peaceful return of Helen of Troy; and other such tales (Rep 379d-e; Iliad 4.866ff). Any portrayal of the gods other than the cause of good would be censored by Socrates.

Socrates’ second law for religious speech and writing is that the god is absolutely simple and truth in both word and deed (Rep 382e).[12] The god does not change or deceive others by visions, words, or sending signs to those awake or asleep; and the gods are not to be portrayed as sorcerers who change their shapes or become liars who mislead (Rep 383a). Socrates again specifically cite passages from Homer as examples of what type of poetry should be censored:

The gods take the shapes of strangers

As they visit the cities of mortals

(Rep 381d; Ody 17.485-86).

Other examples Socrates include are the transformations of Proteus, Thetis, and Hera as well as Zeus sending a false dream to Agamemnon (Rep 383a; Iliad 2.1-34).

Socrates next moves to the poets’ portrayals of the dead and spirits. When the poets depict death, they should do so in a way to make the guardians less fearful of it in order that they may become brave (Rep 386b). When the poets do the contrary, those passages are to be deleted, like the Homeric excerpt when the shade of Achilles speaks to Odysseus in the Underworld:

I would rather toil the soil, a serf to another

To an indigent man without land

Than rule and be king over all the dead who have perished

(Rep 186c; Odyssey 11.489-91).

Socrates continues to list a number of Homeric passages that depict the afterlife as “horrible, noisome, and putrid” (Rep 186d; Iliad 20.64-65); “deprived of one’s senses and understanding” (Rep 186d; Iliad 23.103-4); a life of “shadowy phantoms” (Rep 186d; Odyssey 10.495) where one “wails its doom” (Rep 186d; Iliad 16.856-57) and act like a “gibbering soul” (Rep 387a; Iliad 23.100) that “squeaks and gibbers” (Rep 387a; (Odyssey 24.6-9). Fearful names of the Underworld also should be suppressed and the opposite should be portrayed (Rep 387c). The guardians should be taught that death is not to be fear and that slavery is even worse than death itself (Rep 387b).

The representations of the gods as simple, truthful, and responsible only for good, along with the portrayals of death as something not to be feared, are the models for which the guardians are to emulate. For Socrates, these stories about the gods, the dead, and spirits are to encourage citizens to honor them, their parents, and to value and love each other (Rep 386b). It also introduces the concepts of agency and responsibility for one’s own actions.[13] The guardians will not be able blame external forces, such as the gods, spirits, or a fear of death, for their deeds, if these teachings are to be believed.

Socrates acknowledges the potency of Homeric poetry and the potential danger it brings to citizens – the “more poetic they are the more dangerous” – unless it is supervised by philosophers. Homer is to be admired for many things but not for his depictions of the gods as responsible for evil or that death is something to be feared (Rep 383a). Because of its foundational influence, Homeric poetry is not altogether banished from Socrates’ polis but it is modified to align with the new form of civic education that is required.

II

Socrates continues his censorship of poetry with how the gods, heroes, and people should be portrayed. Poets who claim that the unjust are happy and the just the opposite, that there is profit in injustice, and that justice is another person’s good and your own loss will be prohibited in Socrates’ polis with only the contrary teachings proclaimed (Rep 392b). The poets also will be barred from depicting heroes from doing shocking deeds, like the abductions of Helen and Persephone (Rep 391c-d) or the various examples of Achilles impious behavior: rebuking the gods Apollo and Spercheius (Rep 391a; Iliad 22.15, 20; 23.141-52); disobeying and fighting a god (Rep 391a; Iliad 21.232ff); desecrating Hector’s body (Rep 391a; Iliad 24.15-18); and slaughtering captives (Rep 391a; Ilaid 23.175-76). As a hero, Achilles should not be shown as someone filled with the two conflicting impulses of slavish greed and overbearing arrogance towards gods and humans (Rep 391b-c).[14] Such representations are harmful because they corrupt the young and people would excuse their own evil, being convinced that such things were being done to them (Rep 391e).

The poets should also show that the gods cannot be bribed, as Homer claims with “gifts move gods and gifts persuade awesome kings” (Rep 390e; Iliad 9.515-23) or his portrayals of Achilles accepting Agamemnon’s gifts out of greed, his refusal to release Hector’s body without payment (Rep 390e-391a), or listening to the counsel of Phoenix who urges Achilles to defend the Achaeans if he receives gifts (Rep 390e; Iliad 19.278-81). However, Socrates misrepresents Homer’s account of Achilles, for Achilles has little interest in gifts and is not as greedy as Socrates accuses him to be. Achilles’ objection to Agamemnon was one of justice understood as a type of honor – “but whatever we took by war from the cities have been distributed, and it is not right to take this back from men” – instead of greed (Iliad 1. 124-27). Likewise, Achilles does not return Hector’s body because of want of payment but rather because of his grief over Patroclus. It is only when he overcomes his grief when meeting Priam does Achilles return Hector’s body to his father (Iliad 24.507-15).

This misrepresentation of Achilles is an example of Socrates modifying Homer’s poetry for his own philosophical ends. Socrates may not be interested about the real reason why Achilles refuses to defend the Achaeans but invokes this episode to illustrate a larger, philosophical point about agency and responsibility: if the poets teach the gods can be bribed, then one can excuse one’s behavior and thereby responsibility for one’s deeds. Another reason why Socrates misportrays Achilles is that he finds Achilles’ understanding of justice incomplete: the proper distribution of honor after victory in war. Instead of directly attacking Achilles’ definition of justice, a hero whom the Hellenes admire, Socrates depicts him as greedy and arrogant – a character attack that indirectly questions Achilles’ understanding of justice.

The notion that the gods can be bribed undermines agency and responsibility for oneself, thereby making civic education impossible.[15] This is why Socrates also censors poetry that portrays gods and heroes exhibiting emotional distress, whether Achilles (Rep 387d-388b; Iliad 24.10-12; 18.23-24), Priam (Rep 388b-c; Iliad 22.414-15), Thetis (Rep 388b-c; Ilaid 18.54), or Zeus (Rep 388c-d; Iliad 22.168-69; 16.433-34). This also applies to depictions of laughter, when gods and humans are overcome with it (Rep 389a; Iliad 1.599-600). Such representations of the gods and heroes do not make citizens temperate, teaching them that it is permissible not to control oneself (Rep 388d).

For Socrates, Homer is particularly at fault among the poets for not promoting temperance. He represents Zeus lusting after Hera, forgetting all his plans, and making him want to lie with her on the ground rather than go to their bedroom (Rep 390c; Iliaid 14.294-341). Homer also teaches that “hunger is the most piteous death” (Rep 390b; Odyssey 12.342) and describes Odysseus having said that the best things in life are “tables filled with bread, meat, and full cups of sweet wine” (Rep 390b; Odyssey 9.8-10). But, as Shorey points out, Socrates recitation of the Odyssey is misleading, for Odysseus thinks music rather than food and wine as the best things in life.[16] But this misrepresentation, again, is a way for Socrates to illustrate his larger philosophical point about the need for temperance in civic education. By showing one of the Hellenes’ heroes, Odysseus, lack of temperance, Socrates is able reorient Hellenic civilization towards a more philosophic and virtuous future.

Another instance when Socrates modifies Homer poetry for his own philosophical aims is when he approves Homer’s characterization of Diomede, who says:

Friend, be quiet and attend to my words

And what follows:

In high spirits, the Achaeans march silently fearing their leaders” (Rep 389e).

By citing Homer, Socrates underscores the importance of temperance to be installed into the guardians; however, the two passages do not follow one another, as Socrates claim. The first lines are from Book IV of the Iliad where Diomedes silences Sthenelus after Agamemnon criticizes them (412). The lines that follow, “Friend, be quiet and attend to my words,” are below:

I do not blame Agamemnon, shepherd of the people,

For encouraging the Achaeans to battle.

It is he who receive glory if the Achaeans defeat the

Trojans and take scared Troy,

And he, likewise, will receive all the blame if the Achaeans are slain.

But come, let us call take the thoughts of spirited valor

(Iliad 4.413-18).

This passage does not speak of temperance but about the burdens of leadership and the call for valor.

In the second line, “In high spirits, the Achaeans march silently fearing their leaders,” Socrates splices two different passages from the Iliad into a single one: “In high spirits, the Achaeans march silently, eager at heart to come and aid each other” (III.8) and “all silent as they were through fear of their commanders” (IV. 431). The first line is referring to both the Achaean and Trojan armies advancing to each other for battle before Paris proposes single combat with Menelaus; the second line refers to the same two armies but after the oath is broken.

Although one could speculate about the significance of Socrates splicing lines from before and after the oath is broken, my task here is more mundane. By modifying Homer’s poetry to show how temperance is needed in his polis, Socrates indirectly shows that Homer’s poetry cannot be completely eradicated because of foundational role that Homer poetry plays in making the Hellenes a people. Socrates therefore must resort to censoring those passages of Homer that do not comport with his philosophical project and modify and adopt those passages that do. Admittedly, it is possible that Socrates just misquotes Homer; but I think it more likely that Socrates wants to retain some Homeric poetry because it is impossible to banish it entirely without dire consequences.

III

In spite of his criticism of Homer, Socrates does endorse some of his poetry when it suits his philosophical aims. An example is when Homer describes Odysseus as a model of self-control:

He stuck his chest and chided his heart,

Endure, my heart, for worse you have endured

(Rep 390d; Odyssey 20.17-18).

Socrates also praises Homer as a resource from which the philosophers could learn in the training of gymnastics for the guardians (Rep 404b). Socrates cites Homer’s portrayal of heroes on military campaigns as ones the guardians should emulate: eating only roast meat with fire, as it is the easiest meal to prepare, and not fish, broiled meat, sweets, or any food that comes from pots (Rep 404b-c).

Soldiers also should accept the medical treatment afford them without complaint: nobody finds “fault with the girl who gave the wounded Eurpylus Pramnian wine sprinkled with barley and grated cheese, inflammatory ingredients” or “censured Patroclus who oversaw the case” (Rep 405e-406a). This type of physical endurance is held in contrast to a polis where its citizens have become bloated with self-indulgence and disease. In this city, doctors are required not to cure some common illness but for aliments brought about by an indolent life (Rep 405a, 405d).[17]

Socrates praises these Homeric passages because they align with his philosophical and pedagogical goals of civic education (i.e., teaching guardian children temperance and endurance). And, like previous episodes, Socrates incorrectly recounts Homer’s story by substituting Eurpylus for Machaon (Iliad 11.611-54), a story that he correctly tells in the Ion (538b-d). Machaon is a surgeon and medic, the son of Asclepius who is the god of medicine, while Eurpylus is a great soldier, having entered the Trojan horse. This character substitution allows a better way to appeal to the warrior ethos of the guardians by providing a model of one who is temperate, self-controlled, and can endure the hardships of war. Again, I believe the modification of these Homeric lines are deliberate rather than accidently and underscores the pedagogical and civilizational importance that Homer plays among the Hellenes.

Socrates also praises Homer when discussing about thumos (spiritedness) and the need for temperance to control it. In Book IV Socrates repeats Homer’s description of Odysseus as a model of temperance – “He stuck his chest and chided his heart” – but in the context of understanding the various parts of the human soul (Rep 441b-c, 390d; Odyssey 20.17-18). Here Homer teaches that the spirited part is separate and better than the irrational or desiring parts. Because the spirited part is superior to the irrational part of the soul, it must learn temperance in order for the guardians to know friend from foe. In their training of gymnastics and poetry, Odysseus is one of the models that the guardians can imitate to be temperate (Rep 441d-442d).

The topics of thumos and Homer returns when Socrates discusses how one can identify and honor outstanding soldiers. Socrates cites Homer as a possible resource to teach them: “Even Homer agrees that is it is just to honor the young men who are good” (Rep 468d). An example would be when Homer describes Ajax, who had distinguished himself in war, as being honored with the whole backbone of a boar as the proper reward for his bravery (Rep 468c-d; Iliad 7.321). In this matter, Socrates says “we’ll believe Homer in that much” – an acknowledgment that Homer can teach philosophers about how to identify and honor outstanding soldiers – and reward those soldiers with “seats of honor and meat and full cups of sweet wine (Rep 468d, 390b; Odyssey 9.8-10).

Earlier in the dialogue Socrates cites the same passage from Homer, faulting him for not promoting temperance among citizens, while now he recites the same lines but to praise exceptional soldiers (Rep 390b, 468d). Although he refers to the same Homeric lines, Socrates’ use of them is different because of the new context of conversation: the discussion of warfare and how to distinguish and honor the best soldiers, whereas previously Socrates was examining what type of poetry is best suited for guardian children. One could assume that soldiers raised with philosophically-guided gymnastics and poetry as well as being taught the first two waves (i.e., the sexes are equal and women and children are to be held in common) that they would already be temperate and therefore could safely be seated at “tables filled with bread, meat, and full cups of sweet wine.”[18]

Another instance when Socrates recites the same Homeric lines uttered earlier in the Republic is when he describes how the prisoners in the cave “confer offices, honors, and prizes” to those who are sharpest at spotting the passing shadows on wall (Rep 516d). When observing what his previous inmates are doing, the escaped prisoner feels like Achilles in Hades who rather “toil the soil, a serf to another / to an indigent man without land” than be honored among the prisoners for best spotting the shadows (Rep 516d-e; Odyssey 11.489-90). Although Socrates does not repeat the concluding line of the Homeric passage, “Than rule and be king over all the dead who have perished,” his point is the same: it is better to be a serf outside of the cave than a ruler in it.

IV

Even when Socrates calls for a clean slate when founding his polis, he still refers to Homer. In his analogy of the philosopher as a painter, who looks at the just, beautiful, temperate, and other virtues as models when painting cities and people, Socrates says their judgment is based on “the likeness of humanity which Homer also called divine and god-like when it appeared in humans” (Rep 501a-c). It is not possible for the philosopher to found a polis or educate a people ex nihilo because there is no cultural and civilizational material from which to draw. Socrates acknowledges this situation when he calls Homer as the “educator of the Hellas” (Rep 607a). Homer’s poetry is always present and, for Socrates, pervasive with the result that it must be tolerated but not entirely accepted as is.

While we have seen earlier when Socrates recites Homeric passages to support his philosophical aims, he returns to criticizing Homer in Book X, going back to his initial assessment of his poetry in Books II and III. Although he speaks with “a certain friendliness and reverence for Homer that he has held since childhood,” for he is “the first teacher and beginner of all lovely tragedies,” Socrates honors truth before humans (Rep 595c).[19] Socrates’ primary objection to the poets in Book X is that their poetry is a thrice-removed imitation of reality, with some people believing what the poets tell them is real even though the poets themselves do not truly know (Rep 599a).

Homer is particularly to be blamed when he writes about the greatest and finest things: war, generalship, political rule, and the education of people (Rep 599c-d). Socrates issues a series of challenges to Homer to ask what polis acknowledges him as its lawgiver and benefactor, what war was fought under his leadership, what public service in practical affairs did he do or inventions did he create, or what school of thought he left behind:

Is Homer reported while he lived to have been a guide in education to people whose pupils cherished his companionship and handed down a Homeric way of life, just as Pythagoras was honored for this and his disciples, even to this day, call it the “Pythagorean way,” which distinguishes them from everyone else? (Rep 599c-600e).

The answers implied Socrates’ rhetorical questionings are “no.” But, after closer examination, the correct answer could also be “yes”: as the “educator of Hellas,” Homer has established the civilizational foundation from which politics, war, education, and private affairs have developed for the Hellenes. Although there is no Homeric city, no Homeric way of war, no Homeric philosophy, the poet’s influence is so ubiquitous among the Hellenes that is appears invisible.[20]

However, this is the not the heart of Socrates’ criticisms of Homer. The problem with the poets is that they create thrice-removed images (phantoms) from reality which have “no hold on truth” (Rep 601a). The poet’s phantom is thrice-removed from reality because the poet imitates an imitation of reality and thereby is farthest from the truth when compared to the craftsman or philosopher (Rep 601a-602b-c).[21] For example, the Platonic form of the table is known to the philosopher but is only illustrated by the painter, which is twice-removed from reality (Rep 507a-c; 605a-c). Using the painter’s illustration as a model for his poetry, the poet’s verses are thrice-removed and therefore further away from the truth than either the painter or philosopher. Thus, “all poetic imitators from Homer since” imitate phantoms of everything, including virtue, “but never touch the truth” (Rep 601a).

Furthermore, the poets promote the irrational part in the soul, destroying people’s refinement and putting the rabble in charge of the polis (Rep 605b).[22] Because of the potency of poetry, it can “arouse, feed, and strengthen” the irrational part of the soul where people can distinguish “neither larger nor smaller but thinks the same things now large and now small” (Rep 605b-c). Homer is especially good at this with a grief-stricken hero:

. . . delivering a tirade filled with laments or singing a dirge, while he beats his breast we are thrilled with pleasure; we surrender ourselves to the mood, sympathize with his suffering, and praise the poet as excellent who can most affect us in this way (Rep 605d).

But as a “phantommaker of phantoms who stands far away from truth,” the poet can neither tell the truth nor promote reason but install “an evil regime” (Rep 60b-c). The poet therefore is to be barred from the polis, unless you want “pain and pleasure” to reign instead of “law and principles that are accepted by the community as the best” (Rep 605b; 607a).

Although Socrates only allows “hymns to the gods and eulogies for good humans” into his polis, he does not disparage Homer directly in Book X. Advising Glaucon, Socrates recommends:

. . . whenever you run into people who eulogize Homer as the educator of Hellas, who say that he is worth studying for the governance and refinement of human affairs, and that every person should model one’s life after this poet, you must love and salute them for being the best people they can possibly be, agree that Homer is the most poetic of poets and the first of tragedians . . . (Rep 606e-607a).

Socrates recommends not to criticize Homer directly, for Homeric poetry cannot be completely eradicated in “this ancient quarrel between philosophy and poetry” Rep 607b). Socrates therefore must resort to a different strategy of praising Homer while coopting those Homeric passages that support his philosophical goals and censoring those that do not.

V

Besides censoring some of the content of Homer’s poetry, Socrates also discusses how his poetry should be presented.[23] Socrates classifies three types of styles of poetic presentation: pure narration, imitation, and a combination of the two (Rep 392d). Pure narration is reported – not direct – speech and action; imitation is direct speech or impersonation of people or gods; and the third style is a combination of pure narration and imitation.[24]

To illustrate the difference between pure narration and imitation, Socrates cites the Homeric passage when Chryses asks Agamemnon to release his daughter (Rep 393a-b). When describing Chryses, Homer speaks as himself, an example of pure narration:

And prayed in supplication to the Achaeans

And most of all to the sons of Atreus, the twin commanders of the army

(Rep 393a; Iliad 1.15-16)

But what follows is imitation, when Homer speaks as Chryses rather than as himself (Rep 393b-c).

Instead of concealing himself in his poetry, Homer should only employ pure narration. Showing how Homer should have portrayed Chryses rather than speaking as if he were him, Socrates states:

. . . the priest came and prayed that the gods might give them safely and the destruction of Troy, but they should accept the ransom and release his daughter out of reverence for the gods. When he had spoken, the others consented in reverence, but Agamemnon grew angry and told him to depart and not help him at all. His daughter would not be released, he said, but would grow old with him back in Argos. He ordered him to leave and not upset him, if he wished to get home unharmed. In fear and silence, the old man left, called on Apollo by his names, and reminded him of past favors – sacrifices and temples he had built. In return for these things he prayed that the Achaeans should suffer for his tears by the god’s arrows (Rep 393e-394a; also see 601b).

With the qualification that this example is without meter, Socrates illustrates how Homeric poetry that is imitative in style can be transformed into pure narration (Rep 393d).

Just as he has “described in Homer,” Socrates also permits a combination of the two styles – pure narration and imitation – for his polis but with the understanding that there little imitation and much pure narration (Rep 396e). Imitation is needed for poetry to be effective but must only be a small portion of it because of its potential bad influence in promoting the soul’s irrational part as well as providing bad models for people to emulate. Socrates points out that a worthless person will imitate anything with little or no narration, illustrating the power and problem that imitation poises to the philosopher (Rep 397a-b).[25]

Since the human nature demands that one can only do something well if one imitates only one thing, the guardians should shun “clever imitations of slavish or shameful acts as they would act themselves (Rep 395c). The guardian children should imitate the qualities that make a good guardian: courage, temperance, liberality, reverence, etc. (Rep 395c). Imitation therefore is an effective and “enchanting” pedagogical practice, but it should be employed sparingly and modeled only after virtuous people (Rep 607d).

However, the Republic appears to be a style of poetry that Socrates bans from his polis.[26] The dialogue is either imitation – Socrates recollecting past events and impersonating himself and other people – or a combination of pure narration and imitation but with much more of the latter than the former. But Socrates is not a poet (or, at least, he claims not to be). It is possible that he could be an “advocate” of poetry, as he describes below:

And we would have advocates who are not poets but lovers of poetry to defend in prose and show that she not only delightful but useful to regimes and human living. And we’ll listen favorably, because we will profit if she is shown to be useful as well as pleasant (Rep 607e).

The advocate is someone who recognizes the power and influence of poetry as well as knows how to reform it. Socrates could such a person as he attempts to show Glaucon and Adeimantus that the just life is superior to the unjust one.

Although not a work of poetry, one of the most poetic-like passages in the Republic is the Myth of Er, which describes the soul’s immortality and that its genuine character can be known (Rep 612b). This passage is invoked by Socrates to directly refute Homer’s teaching that the unjust life is better than the just one. In this myth of reincarnation, Socrates weaves characters from Homeric poetry to show how living a philosophical life reaps its own rewards: Thamyras (Iliad 2.595-600), Ajax, Agamemnon, Atalanta, Epeius (Iliad 2.211-77), Thersites (Iliad 2.212-43), and Odysseus (Rep 620a-d) are all shown in making their choices for their next lives. Instead of erasing them from his concluding myth of the dialogue, Socrates incorporate these Homeric characters as lessons of how one should choose justice. He has transformed what he has inherited from Homer into a new mythical founding for Hellas.

Socrates does not have the option of sending poets “off to some other polis” while he will stick to his own “austere and cheerless storyteller because he is beneficial,” imitating only speeches of a righteous person (Rep 398a-b). The influence of Homer cannot be eradicated. Socrates therefore must rehabilitate Homeric poetry as much as philosophy will permit in his re-founding of Hellenic civilization. In this way, Socrates is able to preserve the foundational role that Homer plays for the Hellenes while simultaneously prepare them for a life of philosophy.

Today in the United States, and perhaps even in the West itself, we are confronted with ideological polarization, political unrest, and social conflict.[27] Some have argued for a return to the past of traditional values, while others seek to repudiate it entirely, dismissing it as racist, misogynist, and fundamentally misguided. But these paths of reactionary politics or political revolution are ultimately dead-ends, for what both camps neglect is that our past is neither an arcadia nor antiquated. Our past makes us who we are as a people. We can neither return to it nor can we transcend it. We must learn from Socrates who preserves and reforms what he could from his Homeric past in order to show his countrymen a possible, better future.

References

Adkins, A.W. H. 1972. Moral Values and Political Behavior in Ancient Greece. New York: W.W. Norton & Company.

Ahrensdorf, Peter. 2010. “Homer and the Foundation of Classical Civilization.” In Recovering Reason: Essays in Honor of Thomas L. Pangle. Timothy Burns, ed. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books: 3-16.

. 2014. Homer on the Gods & Human Virtue: Creating the Foundation of Classical Civilization. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Altman, William H. F. 2012. Plato the Teacher. The Crisis of the Republic. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books.

Annas, Julia. 1981. An Introduction to Plato’s Republic. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

. 1982. “Plato on the Triviality of Literature.” In Plato on Beauty, Wisdom, and the

Arts, Julius Moravcsik and Philp Temko, eds.. Totowa, NJ: Rowman & Littlefield: 1-28.

Aristotle. 1932. Politics. Cambridge, MA: Loeb Classical Library and Harvard University Press.

Avgousti, Andreas. 2012. “By Uniting It Stands: Poetry and Myth in Plato’s Republic.” Polis 29.1: 21-41.

Bishop, Bill. 2009. The Big Sort: Why the Clustering of Like-Minded America is Tearing Us Apart. New York: Mariner Books.

Bloom, Alan. 1991. The Republic of Plato. New York: Basic Books.

Brisson, Luc. 2000. Plato the Myth Maker. Gerard Naddaf, trans. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2000.

Burkert, Walter. 1985. Greek Religion. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Burns, Timothy. 1996. “Friendship and Divine Justice in Homer’s Iliad.” In Poets, Princes, and Private Citizens: Literary Alternatives to Postmodern Politics. Joseph M. Knipenberg and Peter Augustine Lawler, eds. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield: 239-303.

. 2015. “Philosophy and Poetry.” American Political Science Review 109.2: 326-38.

Burnyeat, Myles F. 1997. “Culture and Society in Plato’s Republic.” Tanner Lecture on Human Values 20: 217-324.

Collobert, Catherine. 2012. “The Platonic Art of Myth-Making: Myths as Informative Phantasma.” In Plato and Myth. Catherine Collobert, Pierre Destreé, Francisco J. Gonzalez, eds. Leiden: Brill: 87-108.

Danto, Arthur Coleman. 1986. The Philosophic Disenfranchisement of Art. New York: Columbia University Press.

Destreé, Pierre and Fritz-Gregor Herrmann, eds. 2011. Plato and the Poets. Leiden: Brill.

Desstreé, Pierre. 2012. “Spectacles from Hades. On Plato’s Myths and Allegories in the Republic.” In Plato and Myth. Catherine Collobert, Pierre Destreé, Francisco J. Gonzalez, eds. Leiden: Brill: 109-26.

Edmundson, Mark. 1995. Literature against Philosophy, Plato to Derrida: A Defense of Poetry. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Elias, Julius A. 1984. Plato’s Defense of Poetry. Albany: State University of New York

Ferrari, G.R.F. 1989. “Plato and Poetry.” In The Cambridge History of Literary Criticism, Volume I: Classical Criticism, ed. G.A. Kennedy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press: 92-148.

Gadamer, Hans-Georg. 1980. Dialogue and Dialectic: Eight Hermeneutical Studies on Plato, trans. and ed. P. Christopher Smith. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Gagarin, Michael. 1987. “Morality in Homer.” Classical Philology 82.4: 285-306.

Gaskin, Richard. 1990. “Do Homeric Heroes Make Real Decisions?” The Classical Quarterly 40.1:1-15.

Haarmann, Harald. 2015. Myth as Source of Knowledge in Early Western Thought. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag.

Halliwell, S. 2000. “The Subjection of Muthos to Logos: Plato’s Citation of the Poets.” The Classical Quarterly 40.1: 94-112.

Hammer, Dean. 1998. “The Politics of the ‘Iliad.’” The Classical Journal 94:1: 1-30.

Hartman, Andrew. 2015. A War for the Soul of America: A History of the Culture Wars. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Holway, Richard. 1994. “Achilles, Socrates, and Democracy.” Political Theory 22.4: 561-90.

Homer. 1919. Odyssey I. Cambridge, MA: Loeb Classical Library and Harvard University Press.

. 1919. Odyssey II. Cambridge, MA: Loeb Classical Library and Harvard University Press.

.1924. Iliad Books 1-12. Cambridge, MA: Loeb Classical Library and Harvard University Press.

. 1925. Iliad Books 13-24. Cambridge, MA: Loeb Classical Library and Harvard University Press.

Jaeger, Werner. 1939. Paideia: The Ideals of Greek Culture, trans. Gilbert Highet. New York: Oxford University Press.

Kastely, James L. 2015. The Rhetoric of Plato’s Republic. Democracy and the Philosophical Problem of Persuasion. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Kennedy, J.B. 2011. The Musical Structure of Plato’s Dialogues. Durham: Acumen.

Lutz, Mark. 2006. “Wrath and Justice in Homer’s Achilles.” Interpretations: A Journal of Political Philosophy 33.2: 11-32.

Mitscherling, J. 2005. “Plato’s Misquotation of the Poets.” The Classical Quarterly 55.1: 295-98.

Morgan, Michael L. 1990. Platonic Piety. Philosophy and Ritual in Fourth-Century Athens. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Most, Glenn W. 2012. “Plato’s Exoteric Myths.” In Plato and Myth. Catherine Collobert, Pierre Destreé, Francisco J. Gonzalez, eds. Leiden: Brill: 13-24.

Murdoch, Iris. 1977. The Fire and the Sun: Why Plato Banished the Artists. Oxford: University of Oxford Press.

Naddaff, Ramona A. 2002. Exiling the Poets. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Nehamas, Alexander. 1999. Virtues of Authenticity: Essays on Plato and Socrates. Princeton: Princeton University Pres.

Nichols, Mary P. 1987. Socrates and the Political Community: An Ancient Debate. Albany: State University of New York Press.

Nightingale, Andrew Wilson. 2001. “Liberal Education in Plato’s Republic and Aristotle’s Politics.” In Education in Greek and Roman Antiquity. Yun Lee Too, ed. Leiden: Brill: 133-73.

Ober, Josiah. 2001. “The Debate Over Civic Education in Classical Athens.” In Education in Greek and Roman Antiquity. Yun Lee Too, ed. Leiden: Brill: 175-207.

Partee, Morriss Henry. 1970. “Plato’s Banishment of Poetry.” The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism 29.2: 209-22.

Piereson, James. 2015. Shattered Consensus: The Rise and Decline of America’s Postwar Political Order. New York: Encounter.

Planinc, Zdravko. 2003. Plato Through Homer. Columbia, MO: University of Missouri Press.

Plato. 1930. Republic I. Cambridge, MA: Loeb Classical Library and Harvard University Press.

. 1925. Statesman. Philebus. Ion. Cambridge, MA: Loeb Classical Library and Harvard University Press.

. 1935. Republic II. Cambridge, MA: Loeb Classical Library and Harvard University Press.

Riel, Gerd Van. 2013. Plato’s Gods. London: Ashgate.

Rosen, Stanley. 1983. Plato’s Sophist: The Drama of Original and Image. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Saxonhouse, Arlene. 2009. “The Socratic Narrative: A Democratic Reading of Plato’s Dialogues.” Political Theory 37.6: 728-53.

Sweeney, Naoíse Mac. 2015. Foundation Myths in Ancient Societies. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Tanner, Sonja. 2010. In Praise of Plato’s Poetic Imagination. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishing.

Thaler, Naly. 2015. “Plato on the Philosophical Benefits of Musical Education.” Phronesis 60.4: 410-35.

Veyne, Paul. 1983. Did the Greeks Believe in Their Myths? Trans. Paula Wissing. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Voegelin, Eric. 2000. Order and History Volume II: The World of the Polis. Collected Works of Eric Voegelin Volume 15. Athanasios Moulakis, ed. Columbia, MO: University of Missouri Press.

Zuckert, Catherine. 2009. Plato’s Philosophers: The Coherence of the Dialogues. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2009.

Notes

[1] All in text citations are my translation of the Greek text in the Loeb editions. Plato’s Republic is Rep (Plato 1930, 1935) and Ion is Ion (Plato 1925); Homer’s Iliad is Iliad (Homer 1924, 1925) and Odyssey is Odyssey (Homer 1919); Aristotle’s Politics is Politics (Aristotle 1932).

[2] Jaeger 1939; Burkert 1983; Veyne 1983; Voegelin 2000; Ahrensdorf 2010. For more about Homeric values, refer to Adkins 1972; Gagarin 1987; Holway 1994; Hammer 1998; Ahrensdorf 2014; for more about foundational myths, refer to Haarmann 2015 and Sweeney 2015.

[3] For more about the role of how a people’s identity centers around myth, refer to Gadamer 1980, 43; Burkert 1983, 119-25; Veyne, Voegelin 2000, 93-107.

[4] Murdoch 1977; Elias 1984; Annas 1981; Nichols 1987.

[5] Partee 1970; Annas 1982, 11; Danto 1986, 6, 9, 194; Edmundson 1995, 7; Ferrari 1989; Morgan 1990, 156; Burnyeat 1997, 255; Nehamas 1999, 251-78.

[6] Brisson 2000, 75; Zuckert 2009, 475-76; Avgousti 2012, 21-41.

[7] Strauss 1964, 61; Bloom 1991; Most 2012; Burns 2015. Burns interprets Homer as engaging in the same task as the philosopher with an exoteric teaching for the many and an esoteric one for the few.

[8] Brisson 2000; Naddaff 2002; Tanner 2010; Collobert 2012; Destreé 2012; Kastely 2015; also refer to Destreé and Herrmann 2011.

[9] Halliwell (2000) and Mitscherling (2005) adopt a similar approach as mine. However, Halliwell looks at several dialogues without detailed analysis, while Mitscherling seeks only to demonstrate that Socrates does intentionally misquote Homer, with no explanation as to why. Altman (2012) employs a different type of reading, comparing Homer and Socrates but as being confronted with similar philosophical choices. For more about Socrates’ relationship to Homer and the gods, refer to Burns 1996; Planinc 2003; Lutz 2006; Riel 2013; Ahrensdorf 2014.

[10] For more about Hellenic civic education, refer to Nightingale 2001; Ober 2001.

[11] Like Aristotle (Politics 1260b38-1261a17) and contrary to Strauss 1964 and Bloom 1991, I assume the Republic is read as offering an ideal polis.

[12] Socrates also argues that lying is useful only for humans and not gods, if humans act like doctors and treat lying as a type of medicine. Thus, rulers can lie on account of enemies or citizens for the good of the state but citizens themselves should not lie. If any citizen does, he or she will be punished, “whether a prophet or healer or joiner of timbers” (Rep 389b, 489d; Odyssey 17.383-84). Strauss (1964), Bloom (1991), and others interpret this passage as evidence of Socrates’ exoteric and esoteric teachings. However, it is equally possible that lying for the good of the state is an act of statesmanship to preserve the polis from its enemies, while citizens should not lie because it is unjust and appeals to the irrational part of their souls. Although the two readings differ in their interpretation, they are not necessarily incompatible with each other.

[13] Tanner 2010, 45-48; also refer to Gaskin 1990.

[14] For an interpretation of Achilles in the context of changing civilizational values, refer to Bailey 2017.

[15] Another example when Socrates emphasizes human agency and responsibility is when he discusses the correspondence between the types of human characters and the regimes, asking Glaucon whether regimes are derived from human characters or from inanimate, insensible objects, as Homer claims (Rep 544d; Iliad 22.126; Odyssey 19.163).

[16] Shorey highlights this in Plato 1930, 217, footnote delta; also see Aristotle’s Politics (1338a.28).

[17] Socrates later return to medicine with reference to Homer, when he speaks of a civic-minded Ascelpius and his sons who all practice a medicine that only cures diseases and do not prescribe what their patients need to eat or drink because they already possessed temperance. The doctors only “sucked the blood, and applied soothing drugs” (Rep 408a; Iliad 4.218). They did not think that a naturally sick or self-indulgent person should be treated, as they were worthless to themselves and others. Even if they were richer than Midas, the doctor would not treat them (Rep 408b).

[18] Furthermore, as Shorey had noted, Socrates incorrectly recites this passage from the Odyssey, for Odysseus thinks music instead of food or wine as the best things in life (refer to the sixteenth endnote).

[19] Socrates also speaks respectfully of Homer elsewhere in the Republic, even when he is about to censor his poetry. Some examples are “We’ll admire Homer for many things, but not for making Zeus send a false dream to Agamemnon” (383a); “We’ll have to ask Homer and the other poets to forgive us for excising all such lines” (387b); “ask a favor of Homer and the rest of the poets” (387d); and “For Homer’s sake I’m reluctant to say it” (391a). These qualifications of Socrates’ criticisms of Homer reveals the power and hold of Homer’s poetry among the Hellenes. The philosopher therefore cannot completely banish Homeric poetry from his polis but instead cite and modify those passages that support philosophical aims and dismiss those that are contrary.

[20] Refer to the second endnote.

[21] Nehamas 1999, 251-78.

[22] For more about the parts of the soul, refer to Annas 1982, 7-10; Burnyeat 1997, 223, 228, Kirkpatrick 2017.

[23] I do not discuss the musical styles in the Republic as LeMoine does for this symposium (2017); also refer to Kennedy 2011; Thaler 2015.

[24] Pure narration also refers to all literary representation, including direct speech. However, in this article I call pure narration as only reported speech and literary representation as all literary representation.

[25] However, a righteous person does not hesitate to narrate or imitate a good person but with an unworthy person he would be ashamed to do so (Rep 396c-e).

[26] Strauss 1964, 59; Rosen 1983, 19; for a contrary view, refer to Saxonhouse 2009.

[27] For example, refer to Bishop 2009; Hartman 2015; Piereson 2015.

This was originally published in Expositions.