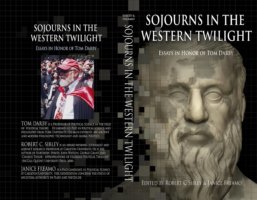

Sojourns in the Western Twilight: Essays in Honor of Tom Darby

Sojourns in the Western Twilight: Essays in Honor of Tom Darby. Robert C. Sibley and Janice Freamo, eds. Eastern Townships, Québec: Fermentation Press, 2016.

Sojourns in the Western Twilight: Essays in Honor of Tom Darby is, as co-editors Robert C. Sibley and Janice Freamo state in the Introduction, an homage to Tom Darby (the much-loved Professor of Political Theory at Carleton University in Ottawa, Canada) and his enduring, “singular Socratic lesson: to seek wisdom to replace one’s ignorance, and to be animated by the love of wisdom” (2). Sibley credits Darby with teaching the capacity to move “along the spectrum of philosophic moods,” and Freamo credits him with “helping to guide and shape her temperament” (1). Darby’s commitment to political philosophy takes place, they claim, at the “discomforting intersection” where “the questing spirit will experience a complexity of moods” (2). In putting together this festschrift, Sibley and Freamo have in fact done much of my work as a reviewer for me: the essays in the collection are already sorted and organized by the complexities of their moods and their themes: 1) Man and Nature (Human and Otherwise); 2) The End of History; 3) The Universal and Homogeneous State; and 4) Political Pedagogy. The volume concludes with Darby’s own contribution, “On Odysseys Ancient and Modern: An Excursus on Spiritual and Causal Explanation,” which brings the unifying themes of much of the volume—homecoming and, as the editors write, the “questing spirit”—to a climax. In this review, I will first treat the sections each with their own address (and the essays contained therein). Second, I will use Darby’s concluding essay to address the themes of the text as a whole (to, in Darby’s words, find the “overarching metaphor[s]” (294)). This is a festschrift that was put together with much love for an inspiring teacher and colleague, and this is evident in every page, and through some excellent pieces of scholarship. I will, however, conclude with a final philosophic mood of my own—a discomforting proposition that this book serves a dual purpose. The first is to honor a beloved Professor. The second, however, is to serve as another kind of festschrift (even, I think, unawares to itself): an homage to a world of political philosophy, and of academia, that in coming home—and returning—to itself in this collection has, in the words of Darby, perhaps experienced its “last voyage” (311).

“Part 1: Man and Nature” contains essays by Gilbert Germain, Donald Verene, David Tabachnick, Horst Hutter, and Barry Cooper. Germain’s piece makes for a nice opening, reflecting on Darby’s concluding essay and on Darby’s work as a whole. So too does Germain establish a guiding theme of many of the pieces in the collection—technology—which Germain links to Darby’s assertion of a “spiritual crisis . . . [issuing] from the boundlessness of the sea upon which the technological juggernaut drifts” (17). Verene and Tabachnick also discuss the consequences of technological living. Verene reflects on the “spiritual zoo” of the Internet and the electronic world, asserting that technology is the “new religion,” and an instantiation of Hegel’s ‘bad infinity’: “the cult of progress is based on the ‘technological bluff.’ The technological bluff is the continual technological act of faith: that whatever we cannot do now, we will be able to do soon” (32). This links nicely with Tabachnick’s essay, which begins with an assertion that the “engine of human progress culminat[es] in the end of history” (37). Tabachnick draws out the manner in which the metaphor of the end of history is being supplanted by the metaphor of “planetary technology”: that is, the end of history collapses into the boundless conception of “citizens of the world” and beyond. Hutter postulates a different sort of future in his piece interpreting “Nietzsche’s ‘Doctrine’ of the Will-to-Power.” While he too moves to the “planetary” sphere—concluding in a discussion of the future “form of struggle for planetary dominion” (64)—Hutter claims that Nietzsche asserts an “affirmation of earthly existence . . .[Which would require] new forms of religious rituals for reshaping the wills of the many, rituals that would emphasize joyful dancing and transporting forms of music that celebrate finite life on earth” (65). [I will say more about Nietzsche’s life-affirmation in my concluding thoughts]. While Cooper’s essay fits least well with the others (thematically), it is a nice piece that focuses on “Kant and Voegelin’s Early Anthropology,” and which directs itself backward rather than forward to the truth of Aristotle’s claim that it is always the case that “philosophy raises anthropological questions” (76).

The next section of the volume, “Part 2: The End of History,” holds the namesake of what it is, really, the focal point of the collection as a whole and of Darby’s philosophical interest and influence. Waller Newell’s “Redeeming Modernity” is a careful analysis of Hegel’s Phenomenology and its “interplay of opposites” in, as Newell writes (one assumes as a subtle homage to Darby), the “odyssey of spirit” (111). Ronald Beiner’s bold essay pairs Kant’s “What is Enlightenment?” with Ishiguro’s The Remains of the Day. Beiner takes an optimistic, and nevertheless provocative, tone in claiming that “modernity is capable of philosophical redemption” through “locating a distinctive moral vision . . .that places the moral universe of modernity on a higher plane than the pre-modern moral universe” (116). Daniel Tanguay focuses on the correspondence between Strauss and Löwith concerning the “Possibility of Overcoming Historicism.” It is a nice tracking of the different periods in which their correspondence reignited, but ends far less conclusively than does either Newell or Beiner’s pieces: in, as one might expect, an aporetic ancient quarrel. H. Lee Cheek Jr. confronts nihilism through an analysis of Psalm 73, diagnosing the “most acute problem of humankind . . . [as a] waywardness at the core” (144). Hugh Gillis concludes the section in an intriguing analysis of how Kojève thought it possible to make the end of history beautiful: through the formalism of Kandinsky’s art. “Both Kandinsky’s art and Kojève’s end of history thesis,” Gillis writes, “represent an exhaustion of possibilities, a kind of limit situation beyond which it is impossible to go” (164).

While the next section bears a different name—“Part 3: The Universal and Homegeneous State”—the concerns of the authors contained within remain much the same as those in the first two groups: the end of history, technology, and (to paraphrase from Timothy Burns’ piece, “What’s Wrong With a World State”) the nightmarish possibilities of the future. Burns sees only a nightmare in the cosmopolitan promise, advocating instead for the virtues of the nation-state and its cultivation of “vigorous ways of life” (190). Phil Azzie’s piece looks to Hobbes’s “Idea of a Universal Sovereign,” tying this to the transition from the “international order animated by the spirit of one religion, Christianity, to a global order informed by the logic and imperatives of another, technology” (201). Gaelan Murphy returns to Strauss, focusing on his dialogue with Kojève, and concluding that in reading their debates we can participate in their call to philosophize as a way of life.

The final section (save for Darby’s own contribution), “Part 4: Political Pedagogy,” begins with an essay by Peter Augustine Lawler. It is by far the most daring of the volume, and Lawler is unafraid to make grand claims about the future of humanity, about the consequences of technology, and about the nature of education. He is engaged with what he sees as the most pressing challenge to humanity (and the hardest evidence for the end of history): the advent of transhumanism and its denial of the “particular [human] destiny of being born to know, love, and die” (241). Lawler’s reflections in this piece are all the more bracing and hard-hitting following his passing in 2017, as is his counsel to live “as a free, living, and relational person in search of truth” (243). Three further pieces provide nice segues into Darby’s concluding contribution: Joseph Khoury’s account of the relationship between political correctness and the end of history, Toivo Koivukoski’s touching and thoughtful piece on what it means to inspire wonder “After the End of History,” and editor Robert C. Sibley’s chapter on Socrates’s having taught and lived as one “who, through the discipline of philosophic logos and the education of his eros, transcended the temporal condition of being to the highest degree humanly possible” (281).

The placement of Sibley’s piece immediately preceding Darby’s own “On Odyssey’s Ancient and Modern” is clearly meant to be a tribute to Sibley’s teacher. The mark that Darby has left on his students and colleagues is one that has both inspired an emulation of Darby’s philosophic mode of inquiry in the classroom, and his teachings and lessons about history, politics, and technology. Darby’s final essay, focusing on odysseys, is a reflection on the odyssey of philosophic inquiry, of history, and of the individual human life. Like many of the contributions in the volume, however, Darby’s last word ends if not pessimistically, then ambivalently, about the future of humanity and of philosophy: “technology is the sea upon which we have set sail after having walked aboard our chosen ship. This is our odyssey and perhaps it is our last voyage” (311). While Darby concedes that there is, perhaps, hope, this is a whisper of optimism in comparison to the raging ocean that stretches indefinitely into the horizon: the very end of history that it seems Darby maintains has arrived and is inescapable. And so too, as this poignant festschrift makes evident, have many of his students and colleagues boarded this ship to sail off with him on this “overarching metaphor” into the Western Twilight.

Here then we arrive at my discomforting contribution. This ship, just as a ship of antiquity, has no women on it. Not one contribution. I do not mention this in passing, nor do I mention it out of a sense of political righteousness or personal, feminized insult. It goes much deeper than this, and is, I think, an inevitable consequence of the very thesis that dominates the volume: the end of history. That is, this is a philosophical problem in addition to being a political one. The chosen ship of this volume’s odyssey is the end of history: the end of a “vigorous”, thumotic, and penetrating pursuit of truth that has no more fecundity. We have, it is said, arrived at the “last man” and the technocratic banality of modernity. The end of history is the end of an odyssey that sees its conclusion as closed and inescapable, just as Heidegger sees Being-Towards-Death as the only form of authentic existence. It portends its own barrenness, and so becomes consumed in its ineffectual solipsism and pessimism.

Indeed, the language of barrenness is invoked more than once to describe the end of history and modernity. Newell writes in his contribution that “for us moderns,” “the world is barren” (106). Hugh Gillis writes of the end of history (or, rather, of Kojève’s account of the end of history) as the “exhaustion of all possibilities, of a kind of limit situation beyond which it is impossible to go” (164). Historicism, spiritual crisis, philosophic stasis, the confrontation with nihilism, modernity’s oppressive banality, are all cited as instantiations of the end of something—the historical and philosophic odyssey—that had once been fecund but is now face-to-face with the inevitability of its own incapacity to regenerate itself. This is a volume consumed with barrenness and the death of philosophic and historical possibility. This barrenness is, however, an inevitable conclusion for a worldview whose “overarching metaphor” is one of male fortitude, and philosophic penetration.

The female lurks as a spectre throughout, haunting the virile pursuit of philosophy. Indeed, Darby ties his homecoming to thumos, or the spirit: “homecoming implies self-knowledge, and therefore, that for which one is fitted . . .It is about the realm of spirit, which is concerned with action, purpose, courage and honor” (292). Its bedfellow, hospitality (linked explicitly to the bed of Odysseus and Penelope), “relates to various manifestations of codes of conduct” and “is the germ of politics” (293). While Darby wants to call their union “stable” it is clear throughout that the emphasis on the “major odysseys” of the Western tradition are ones of homecoming, not home-keeping, and women (or, the “female”) are merely stops along the way in the pursuit of knowledge.

But it is always the female that has been the site (both in actuality and in metaphor) of what is new, of rebirth, and of the possibilities of the future. Diotima (not discussed in Sibley’s piece on eros) is the source guiding us to the love of ideas; Athena is the goddess of wisdom. Socrates concluded his life not as a warrior, but as a midwife. In his final essay, Darby does tie “the home” to the female, in a comparison of Odysseus’s return to Penelope to the relationship between our modern Ulysses, Leopold Bloom, and his cuckolding wife Molly: “Odysseus’s homecoming is to faithful Penelope—faithful for twenty years during her husband’s absence. But Joyce’s novel ends with the wife of the cuckolded Leopold Bloom, Molly Bloom, and her effusive swoon over the delights with her lover, Blaze Boylan. Leopold Bloom is a man bereft of spirit or purpose. He is Nietzsche’s ‘man without a chest,’ a Last Man, the last man of the West” (310).

Leopold Bloom is here presented as the literary representation of the hollowness of modernity: he has been abandoned, cuckolded, left behind. He has no home to conclude his voyage. The end of history lacks purpose, expressed in and as a barren modern future, lacking vigor and containing only soccer moms. As Khoury approvingly cites, Darby’s vision of the female future is captured best in his Disorderly Notions: “thus the future will have come, and then be gone forever, and the universal and homogeneous world at the end of history will be one eternal world of nice, white, American women” (250).

But perhaps here the issue is in the very fact that Molly is treated as a home that has left, rather than as a figure that remains in and of herself. Ulysses does not end with Leopold, but with Molly. And indeed it ends with Molly in a state of menstruation, of fecundity, concluding the narrative with the last words not of a last man, but a life-affirming “yes.” A stark contrast to Leopold’s sad deposit in the sand in the Nausicaa episode, Molly’s soliloquy—the final word—is an affirmation of possibility. If Leopold is the Last Man, Molly is Nietzsche’s life-affirmer. In Beyond Good and Evil, Nietzsche writes that philosophic pessimism also opens itself to an “inverse ideal”: “the ideal of the most high-spirited, vital, world-affirming individual” (BGE §56).[1] To focus on what has been spurned (Leopold) at the expense of the woman is precisely the content of Nietzsche’s prefatory provocation: “suppose that truth is a woman—and why not? Aren’t there reasons for suspecting that all philosophers, to the extent that they have been dogmatists, have not really understood women? . . . What is certain is that she has spurned them” (BGE Preface).

If the end-of-history thesis results only in a vision of the future that is barren and bereft of spirit, purpose, and philosophy, we need to be reminded that there is another future that is possible in the promise of something new, of birth. The future is female. To use Darby’s terminology, the “overarching metaphor” persists: the possibility of philosophy, and the birth of new ideas, will always be, as it has always been, female. Nietzsche’s yes-man is a woman. I read this volume, thus, as a festschrift to the end of history, and the barrenness of philosophy and academia. It is an homage, and as robust and full of honor as it could be, to an end that is seen as such only because it has always been incapable of seeing a new beginning. As Joyce wrote in a letter to Frank Budgen (1921): “the last word (human, all too human) is left to Penelope.” Thus, in those last words of Molly Bloom, and of Joyce’s modern Odyssey, we find our task: “and yes, I said yes, I will Yes.”

Notes

[1] Friedrich Nietzsche, Beyond Good and Evil, ed. Rolf-Peter Horstmann and Judith Norman, trans. Judith Norman (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002).