Stuart Holroyd, Gnosticism, and the Occult Wave

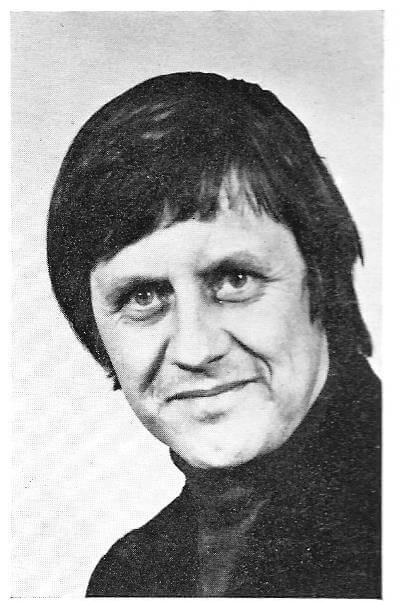

The name of Stuart Holroyd (born 1933) is associated – if rather erroneously – with that British literary insurrection of the late 1950s, the “Angry Young Men.” In fact, Holroyd and his two close associates, Colin Wilson and Bill Hopkins, differed strongly from the “Angries,” among whom the representative figures were John Osborne, Kingsley Amis, Harold Pinter, and Kenneth Tynan. The “Angries” emphasized their politics, leaning strongly to the left; they assumed an ostentatiously materialistic viewpoint, wrote in self-righteous condemnation of the existing society, put ugliness on display, and tended towards an egocentric species of pessimism or nihilism. Osborne’s Look Back in Anger, which enjoyed theatrical success in London in 1956, typifies the outlook of the “Angries”: It presents an English version of Jean-Paul Sartre’s bleak Existentialism, set in a universe devoid of meaning where, in Sartre’s phrase, “Hell is other people.” Holroyd and Wilson, and to a certain extent Hopkins, could not content themselves with the restricted mental horizon of the “Angries.” Nor did they wish to waste energy “condemning society.” Holroyd and Wilson especially responded to a shared mystical impulse that saw in human nature possibilities of transcendence. Wilson remains better known than Holroyd, but their early careers ran on parallel tracks. Wilson published his first book, The Outsider, in 1956. It became an unexpected best-seller. Holroyd published his first book in the same year although it appeared in print after The Outsider had come out. Emergence from Chaos exceeds The Outsider in a number of ways – it is better organized, its prose more finished, and its arguments more coherent. Both books recount indirectly a type of metanoia springing from the inveterate reading, since adolescence, of serious books, in Holroyd’s case with a focus on poetry and philosophy, Wilson’s Outsider being oriented more to the novel.

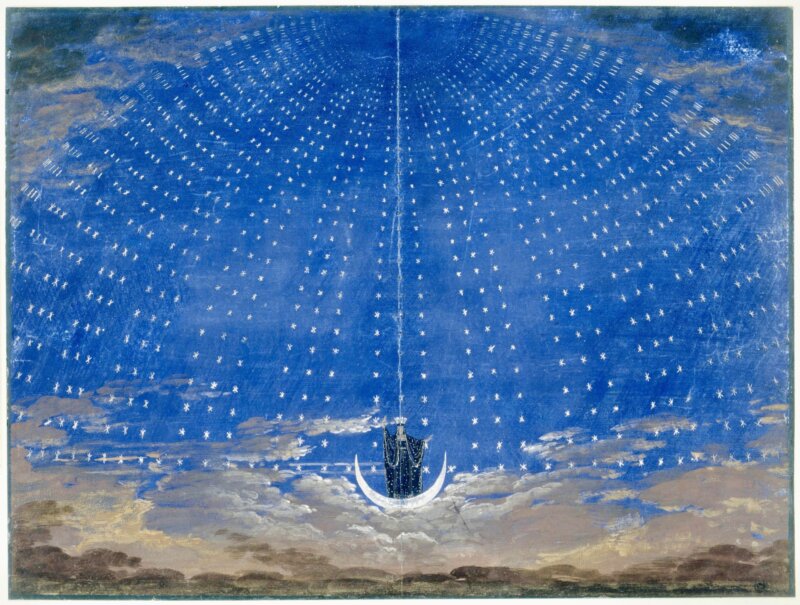

I. Emergence from Chaos proposes the overarching thesis that religious or spiritual experience drives human development, both for the species, historically speaking, and for the specimen individual at any given moment on the historical continuum. Holroyd, as expected, defines religious experience broadly; he will not confine himself, say, to the standard tale of Christian conversion although he by no means excludes it. Holroyd focuses on effects. Mystic ecstasy comes in many varieties, which “have different causes,” as Holroyd writes in Chapter One, “and are expressed in different terms”; but “they always lead to the same metaphysical conclusions.” The subject espouses the new conviction that “there is a higher reality than the obvious, tangible, worldly reality, and man is most nearly himself, lives most intently, when he seeks to embody or to exist upon this higher level.” Spiritual experience “thus leads to a severe shaking of the foundations upon which the lives of most of us are built.” The initiate often interprets his access to the vision as both a rebirth and a type of humblement. He tells of what has befallen him, but he makes no egocentric claim about it. He now sees the ego in its proper place in the divine-cosmic hierarchy. In Chapter Three, Holroyd discusses the conjunction of “Religion and Art.” Holroyd makes the point that, “Art is not religious because it concerns itself with obviously religious subjects, but rather because the artist’s attitude to life is a religious one.” Holroyd cites the still-life canvasses of Paul Cézanne where the intensity of the painter’s vision functions as the mark of his exalted spiritual state.

Again in Chapter Three, Holroyd contrasts the genuine religious attitude with its false and all-too-common counterpart. He characterizes the latter as something sophistical: “The pseudo-religious attitude measures all things with the yardstick, Man.” On the other hand Holroyd perceives in the real thing “a certain anti-human element” that correlates with the revelation of “an absolute set of values.” Holroyd therefore rejects Humanism. He writes how “when the Humanistic categories dominate men’s minds they encourage a flaccid and sentimental way of thinking”; whereas on the other hand, “genuine religious art has a certain hardness, precision and austerity which Humanist art lacks.” The urge to transcendence comes into its own, as Holroyd puts it, “in a reaction against the ugliness, imperfection and transience of worldly things” and involves “spiritual suffering… that restlessness of the spirit which urges the mind to be ever seeking answers to the eternal questions.” Holroyd alludes to T.S. Eliot’s Four Quartets, especially to “Burnt Norton,” as exemplifying the hardness and dissatisfaction that he invokes. He also makes reference to the sufferings of Ivan in Fyodor Dostoevsky’s Brothers Karamazov. In Part Two of Emergence, Holroyd devotes the chapters to a number of case studies, such as W. B. Yeats, Rainer Maria Rilke, Arthur Rimbaud, and, in his final chapter, Eliot. For Holroyd Eliot embodied “the intellectual soul,” a variant on mystic or visionary proclivity. “The intellectual soul,” Holroyd writes, “is found in the man who is endowed with the metaphysical need of finding an explanation of the world and his own place in it.” Moreover, as Holroyd adds, “faith does not come easily to him; it is not a natural disposition… or an inherited and unquestioned belief.” Rather the intellectual soul attains his surety of faith by discipline. The goal is “the forming of the future,” or the betterment of the world, but only by a rigorously unsentimental program that avoids the reductive themes of a failed modernity.

Holroyd produced two quasi-sequels to Emergence in Flight and Pursuit (1958) and Contraries: a Personal Progression (1975), both of which confirm the crypto-autobiographical interpretation of the earlier volume. The hiatus between Flight and Pursuit and Contraries signified Holroyd’s immersion in other activities. He produced occasional literary work in articles and reviews, wrote for television, and authored a textbook on literary studies (The English Imagination, 1969); but his main activity in this period seems to have consisted in the establishment and perpetuation of a language-school franchise. When with Contraries he resumed writing books, his direction had changed. While Contraries, a memoir of the 1950s, resumed the seriousness of Emergence and Flight, the remainder of Holroyd’s authorship suggests a commercializing attitude. Holroyd produced books on psychic phenomena, extraterrestrial intelligence, sex, and Eastern religiosity, topics which in the 1970s and 80s exerted a strong appeal on the public imagination. Wilson too had exploited such popular interests in The Occult (1971) and Mysteries (1978). Holroyd himself has referred to his latter-day exploits as “literary whoring,” a phrase that indicts the latter part of his oeuvre more severely than necessity requires. Being a keenly intelligent and massively educated man, Holroyd, even where it concerns outré or faddish topics, always manages to devise a nourishing, as well as an entertaining, exposition. He knows that even a delusion will yield a meaning if interpreted in its proper context, according to its symbolism, and with requisite sensitivity to its connotations. He knows further that eccentricity often functions critically with respect to the social conformity against which it rebels.

Consider Alien Intelligence (1979). The book shows no little continuity with Emergence and Flight, sharing with them a preoccupation with mystical experience and the philosophical metanoia. Holroyd comments, in his introduction to the book, on Olaf Stapledon’s visionary, science-fiction epic Star Maker (1937), which deals with the development of mentality on a cosmic level and dramatizes the yearning of the Cosmic Mind, once synthesized, to fuse with its absolute Other – the titular “Star Maker.” A reader who, like Holroyd, permits Star Maker to absorb him will, to borrow a phrase from Emergence, experience vicariously “that restlessness of spirit which urges the mind to be ever seeking answers to the eternal questions.” Returning to Stapledon in the book’s final chapter (“Supermind”), Holroyd characterizes Star Maker as a prolonged, mythopoeic meditation on “the immensity of creation and… the dependence of the Creator upon his creation”; Stapledon’s speculation underscores, as Holroyd states, “the interdependence of creator and creature.” Holroyd invokes a variety of Imitatio: God, a higher being, exercises his potency through creation, implying “that to seek and create and to evolve is to participate in the divine purpose and nature.” Holroyd’s reading of Stapledon affirms the sacredness of creation, whose fundamental basis is “God-stuff.” Given that “God-stuff” is psychic, the Cosmos would then be “minded.” Thus in a slightly wacky volume aimed at customers of what, in the 1970s and 80s advertised themselves under the comical name of “metaphysical bookstores,”[i] the commercializing writer validates the Platonic notion of the universe, reinserting a traditional philosophical idea, that of the ordering Logos, into popular discourse.

Holroyd’s Elements of Gnosticism (1994) takes its place, with qualifications, in the milieu just mentioned – that wave of interest in the 1970s and 80s in alternative religiosity, a new spiritualism, and a misnamed metaphysics that might more honestly have called itself theosophy. The scholarly literature on the Late-Antique Gnosis has a lengthy pedigree. It could be said to originate in the heresiology of the early Christian writers, but as proper scholarship it can trace itself to the early Nineteenth Century, in such weighty tomes as Ferdinand Christian Baur’s Manichaeische Religionssystem (1831) and Christliche Gnosis (1835). By the fin-de-siècle, the bibliography of Gnostic studies had waxed copious. The repressed heresy exerted its appeal again in the new century, on the scholarly level, in two key events. In Egypt in 1945 a collection of Fourth-Century Gnostic tracts, called the Nag Hammadi Library after their provenance, turned up and the decades-long project of translating them from the original Coptic began. In 1958, on the basis of what so far had been translated, philosopher Hans Jonas published his ambitious study of The Gnostic Religion, with the subtitle The Message of the Alien God & the Beginnings of Christianity. Jonas, a former student of Martin Heidegger, argued that the intellectual complexities and convoluted symbolism of the Gnostic writings made them more than just an antiquarian curiosity; he saw in Gnostic thought an “anti-cosmic” theme that betokened a radical rejection of Hellenistic science and theology. Jonas also argued, in an appendix to the revised edition of The Gnostic Religion, that antique Gnosticism had modern analogues, citing especially the existentialist philosophers including his old teacher Heidegger.

II. No few books about Gnosticism, whether scholarly of character or popularizing, followed in the wake of Jonas’ best-known opus. On the academic side there were, outstandingly, Kurt Rudolph’s Nature and History of Gnosticism (1983), Giovanni Filoramo’s History of Gnosticism (1990), and Yuri Stoyanov’s Other God (2000), to name only three titles among many more. On the popularizing side one might cite Stephen Hoeller’s Gnostic Jung (1982), Tobias Churton’s Gnostics (1987), and Elaine Pagels’ Gnostic Gospels (1989), once again to name only three titles among many more. Respecting The Gnostic Gospels, it could boast an academic author – at the time of the book’s appearance, Pagels enjoyed a tenured professorship at Barnard College – but the publisher clearly intended it for a laical audience, the people namely who bought Hoeller’s Gnostic Jung and Churton’s Gnostics and who shopped for them at “metaphysical bookstores.” Pagels, who grew up in an evangelical community, had in her teens suddenly revolted against her Christian instruction. The authorial attitude in The Gnostic Gospels tends toward a type of reactive sectarianism which expresses itself, sometimes directly and sometimes indirectly, under a distinctly proto-postmodern and anti-Christian mood. Pagels, for example, levels the charge of literalism against the Orthodox account of Christ’s resurrection, calling it “wholly implausible.” She next reverts to a crudely Marxian thesis. “The doctrine of bodily resurrection,” Pagels writes, “serves an essential political function: it legitimizes the authority of certain men who claim to exercise exclusive leadership over the churches as successors of the apostle Peter.”

Pagels, in the course of her chapters, discovers in the Gnostic Gospels the full suite of contemporary liberal affirmations. The Gnostic dissentients were proto-feminists; indeed, they re-inserted a goddess into the theological scheme, to be venerated equally with the god. The Gnostics anticipated Feuerbach and Nietzsche in reallocating aspects of an alienated godhead to humanity. Theirs qualified as the real humanism, which the Church always strove to quash. Pagels, however, consistently mischaracterizes Orthodoxy, which she refers to repeatedly as monotheistic. Judaism and Islam are monotheistic. Christianity is Trinitarian; its god manifests himself in three distinct persons – the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit. Pagels’ charge of literalism in respect of the resurrection also misfires. Far from purging the resurrection of symbolic meaning, the Patristic writers endow on Christ’s return to living flesh a vast range of far-reaching connotations. Nor does Orthodoxy reduce the resurrection to a literal-minded implausibility, as Pagels argues. Rather, Orthodoxy presents the resurrection as a mystery, in awe before which neither the peasant nor the scholar can offer explanation. Gnosis reveals itself contrarily as the opposite of mystery; it takes the form of a type of knowledge, granted only to an elite class, which possesses the absolute degree of certitude. The Gnostic’s everything-you-previously-knew-is-wrong type of illumination functions emblematically like the modern humanities doctoral degree – it certifies its bearer as wiser than others and therefore also as the dispenser to others of a mandating wisdom.

Holroyd lists The Gnostic Gospels in his bibliography along with titles by Churton, Hoeller, Jonas, and G. R. S. Mead. The Elements of Gnosticism, written by a college drop-out and washed-up actor, differentiates itself from Pagel’s book, and all those that hit the shelves of the metaphysical bookstores in the same decade, first of all in its tentative voice. The phenomenon of Gnosticism – in its elaborate intellectual constructions, its contrariness, and its stubborn persistence – fascinates Holroyd. He wishes to share the object of his fascination with his readership. Unlike Pagels, Holroyd has no axe to grind. He appreciates the intrinsic allure of Gnosticism, but without wishing to espouse it as such and without too heavily apologizing for it. Readers of Holroyd will discover the background to this tentativeness in his earlier books. Flight and Pursuit and Contraries record serious episodes of self-examination and set out the influences and arguments by which, through several alterations of conviction, the book’s author arrived at his reconciliation with a faith in God. This event implied a corollary. If Holroyd’s early life had consisted in a good deal of disorderliness, one of the grounds on which he could re-gruntle himself was that he lived in an orderly universe – if not at the social level, full of corruption, then at the cosmic and divine levels. Men’s troubles stem from their errors and misdeeds, not from the God whose sole desideratum for men is to love. The Elements, for its part, sets forth its survey in seven chapters: “Gnosticism Ancient and Modern”; “Gnosticism and Christianity”; “The Major Schools of Gnostic Thought”; “The Gnostic Religions”; “Gnostic Literature”; “The Legacy of Gnosticism”; and “The Gnostic Revival.”

Holroyd readily perceived that certain aspects of modernity wear a Gnostic guise. In his first chapter, he remarks on the Gnostic proclivities of notable literary figures of the last three centuries. Holroyd proposes the following names as members of the Gnostic club: “Voltaire, Goethe, Blake, Melville, Yeats, Jung, [and] Hesse.” Under the claim that “there is . . . a substantial corpus of modern Gnostic literature,” Holroyd invokes “the literary-philosophical school of Existentialism,” which can boast “many affinities with classical Gnosticism.” Later, in Chapter 7, Holroyd returns to these names, but in most cases his explanations fall short of full persuasiveness. Voltaire seems somewhat alien to a list of Gnostics, except that he rejected the standard theodicy and introduced into Candide a character who describes himself as a Manichaean. Goethe qualifies as visionary, but to conflate vision and gnosis would be an error. Blake makes a better candidate than Goethe: His “Nobodaddy” resembles the Gnostic Demiurge. Melville, in Moby Dick, linked Captain Ahab to “the ancient Ophites,” but that served the purpose of underlining Ahab’s fanaticism, a gesture that cannot, by itself, induct Melville’s novel into the ranks of Gnostic belles-lettres. This is so despite the fact that Melville took an interest in Gnosticism. One could say the same of Yeats as one says of Goethe. Now Jung and Hesse, on the other hand, knew of Gnosticism, felt its allure, and might indeed have espoused it – but the latter’s Glass Bead Game could easily be interpreted as a critique rather than an expression of late-modern Gnosticizing elitism.

In the statement about Existentialism, which also omits to explain itself, the influence of Jonas makes itself felt, but only readers of Jonas would sense this. Invoking Existentialism as a positive instance of the contemporary Gnostic presence, Holroyd in fact puts himself in something of a contradiction. In the late 1950s Wilson, Hopkins, and Holroyd saw themselves as constituting the English school of Existentialism. Their brand of Existentialism differed considerably from the French brand; and Holroyd’s particular brand incorporated a belief in God, as already mentioned. In Flight and Pursuit, Holroyd devotes his final chapter to a convincing critique of Sartre’s argument for atheism, as set forth in Existentialism is a Humanism. Holroyd notices that Sartre cannot help but endow a character on the god whose reality he denies, treating him as though he existed. This god, “Sartre’s God,” holds himself remote from humanity, never advises his creatures, permits the rampages of evil, and is therefore complicit in them and tainted with sadism. Or rather he would be if he existed, but he is not supposed to exist. As Holroyd suggests, however, Sartre’s rhetoric creates ambiguity with respect to the existence or non-existence question. Sartre paradoxically requires the god who does not exist in order to carry forward his argument.

From the retrospective viewpoint of Elements, “Sartre’s God” in Flight resembles the Gnostic Demiurge. Consider the parallelisms. Sartre concluded in his pamphlet, as Holroyd reports, that the grounds for positing a deity were entirely lacking and that, therefore, without a divine source no transcendent meaning, such as theology asserted, inhered in the universe. Men could make no valid appeal beyond this world. The Gnostics, for their part, perceived in the Demiurge a false god, to worship whom entailed a degrading delusion and a blasphemous disregard for man’s potential dignity. The false god’s botched world, moreover, held no meaning; in it, humanity wandered lost, abandoned, and with only a few illuminated souls yearning for redemption. For Sartre, such meaning as might be produced in this, the only, world would derive solely from the will of men; or rather from the will of those whose intellectual endowment and volitional fortitude (“commitment”) enabled them to make their own meaning and in so doing to substitute for the non-existent creator. In the Gnostic view, most men could not discern the wretchedness of their condition; only an elect few possessed that broadcast particle of the true god, or of his environment, the pleroma, in following the compass-needle of which they might reascend to unity with the divine. Sartre’s denunciation of the bourgeoisie implies an analogous conviction. Where the Gnostics leap beyond the false god to the true god, Sartre retreats from the non-existent god back to a charmless, café-dwelling version of Nietzsche’s superman, who through his engagement, in those moments when he leaves the café, elevates himself above the common run of men.

III. Holroyd’s case for Gnosticism remains nevertheless a measured one. Unlike Pagels, Holroyd’s attitude is not, against Orthodoxy, an angry one. In Elements, Chapter 1, in setting forth the common propositions of the numerous Gnostic systems, Holroyd remarks that “the idea that the world was the work of an incompetent or malevolent deity” figures among them. He adds that, “stated thus baldly, it seems a merely perverse idea, or an attempt to exonerate human iniquity by putting the blame on God.” He immediately tries to downplay the perversity by explaining that the Gnostic systems posit two deities: The inferior Demiurge who, envying the creative potency of the superior deity, authors the botched world; and that selfsame superior deity, sometimes referred to as the Father. Holroyd notes that the “transcendent God does not, and never did, act, in the sense of willing something and bringing it about.” Rather than create, as does the God of Genesis, the Father emanates the lower levels of the metacosmic hierarchy in which he dwells, whatever that means. Thus, to think like the Gnostics, “we have to substitute the idea of divine emanation, or ‘bringing forth,’ for the idea of divine action.” In Gnostic rhetoric, the Demiurge is the “abortion” of Sophia or Wisdom. When the Demiurge came forth from Sophia, then, in Holroyd’s words, “he imagined himself to be the absolute God.” Holroyd makes a good job of conveying to his readership the baroque complexity of the Gnostic myth, with its many levels of divine and demonic beings and its multi-stage causality that brings about the world as men know it.

Holroyd writes, again in Chapter 1, that “in some Gnostic schools the savior bears the name Christos, or Jesus, but there is a fundamental difference from Christian belief in that the Gnostic Christ brings salvation not from sin but from ignorance, offers not redemption but the knowledge that redeems, and demands not belief and contrition but spiritual effort and diligence.” Holroyd writes that: “There is an obvious elitism implicit in this. To be awakened to the existence of the divine spark within is in itself to be set apart from the majority of mankind, and actually to possess the gnosis is to attain a rare spiritual distinction.” It is the case, as Holroyd sees it, that “the Gnostic contempt for the material and physical world can easily be extended to contempt for human beings who do not see anything intrinsically wrong with the world, and the contempt for the Creator can result in the repudiation of moral principles and prohibitions and the assumption of a status above the law, where anything is permissible.” That last phrase alludes to Fyodor Dostoevsky’s Brothers Karamazov, in which Ivan Karamazov declares that, “I do not accept the world that [God] created,” and adds that in the rejection of God, “Everything is permitted to the intelligent man.” Intelligence! Is it not the same as gnosis? Holroyd’s allusion is tantalizing.

Holroyd writes in Elements, Chapter 2, of Gnostic stubbornness: “The Gnostics did not take kindly to authority.” As with the mentality of Ivan in Dostoevsky’s novel, “there were those among them who repudiated all terrestrial authority on principle, as deriving from the counterfeit God who created and governs the world.” Holroyd’s assertion that the Gnostics “had no vested interest in exercising authority” seems, however, baseless. Indeed, a non-Christian commentator, the Third-Century Neo-Platonist philosopher Plotinus, devoted an essay to the Gnostics (Enneads, Book Two, Section Nine) in which he describes their fanaticism and their arrogation of a presumptive authority that exceeds all other authority. Members of a Gnostic sect rudely interrupted Plotinus’ lectures. For his part Holroyd notices the absence of caritas in the Gnostic doctrine: “The meek, the poor, the burdened, the captive and oppressed, the sick and the maimed, the little children are not the beneficiaries of the gnostic Jesus’ ministrations.” Later in the discussion, he writes that, “Undeniably there is something inhuman in Gnosticism, even anti-human, a repugnance felt and expressed for all things we associate with being human, which no doubt in part explains why orthodox Christianity, with its emphasis on the humanity of Jesus, prevailed.”

Not incidentally, these words would apply to Sartre’s philosophy, as Holroyd represents it in Flight. Indeed, in Elements, Chapter 7, in the context of justifying his classification of Existentialism under the rubric of gnosis, he returns to Sartre. Holroyd is thinking of Sartre’s Nausée when he writes that, “Existentialists, like the Gnostics, tended to regard the material, physical world, with repugnance, as constituting a mode of being utterly different from and inimical to the mode appropriate for men.” Holroyd invokes Sartre’s categories of “en soi” and “pour soi,” the former referring to mute objects and the latter to subjectivity. In Holroyd’s view, “Existentialism endorses the fundamentally gnostic view of the human condition as one of entrapment in an ‘inauthentic’ mode of existence, and that… escape from the trap demands a sustained mental effort of awareness.” This very “sense of entrapment” unites Sartre’s universe with the shared universe of the “Angries,” who whine about the wretchedness of an empty civilization while at the same time wallowing in it. For the “Angries,” at least, and quite possibly also for Sartre, authenticity is a spurious goal. Authenticity serves only as a rhetorical position from which to designate and denounce inauthenticity. Negativity permeates the practice of the Sartrean Existentialist – it hints at a desire to be conspicuous for conspicuity’s sake.

Holroyd wonders whether Oswald Spengler’s thesis of an inevitable civilizational decadence might explain the re-emergence of exotic religious ideas, especially those related to Gnosticism, in the current era. In The Decline of the West, Volume II, in a section devoted to Pythagoras, Mohammed, and Cromwell, Spengler adduces two phases of religious decline – what might be called religious frivolity and what he names as “the second religiousness.” In respect of the former Spengler writes: “Materialism would not be complete without the need now and then easing the intellectual tension, by giving way to moods of myth, by performing rites of some sort, or by enjoying with an inward light-heartedness the charms of the irrational, the unnatural, the repulsive, and even, if need be, the silly.” As to the second religiousness, which follows religious frivolity, Spengler writes that it “consists in a deep piety that fills the waking consciousness.” The second religiousness emerges from rationalism, which for Spengler is already something defective, by way of negation. The renewed piety “starts with Rationalism’s fading out in helplessness,” whereupon the archetypes of “primitive religion” reappear “in the guise of a popular syncretism that is to be found in every Culture at this phase.” Whereas the structure of this piety is composite, its attitude is monistic and puritanical.

Spengler’s insight has considerable relevance for cultural phenomena under discussion. Take, for example, Holroyd’s late authorship, concerning which Holroyd himself used a diminishing vocabulary. In addition to Alien Intelligence and Elements, Holroyd wrote during the period from the late 1970s to the early 1990s Dream Worlds (1976), PSI and the Consciousness Explosion (1977), Mysteries of the Inner Self (1978), Briefing for the Landing on Planet Earth (1979), The Complete Book of Sexual Love (1979), Quest of the Quiet Mind (1980), and Krishnamurti: The Man, the Mystery & the Message (1991). As the titles indicate, these books furnished part of the vast bibliography of so-called spiritual and occult books that flooded the market – and found a large audience – in the first phase of post-1968 modernity. The subject-matter of these tomes corresponds to Spengler’s paradigm of cultic divertissement in the phase of religious frivolity.[ii] Holroyd addresses Jung’s Unconscious and its archetypes, telepathic contact with alien beings, the allure of an intensified consciousness, a type of Tantric discipline, and the life and teachings of an exotic guru. Holroyd’s titles take their place in a catalogue that includes, in addition to similar titles by Wilson, the Seth books by Jane Roberts, the alien-abduction books by Budd Hopkins, and the series beginning with Holy Blood, Holy Grail by Michael Baigent, Richard Leigh, and Henry Lincoln.

How to sum up the Occult Wave, the reverberations of which are felt even today? If it were frivolous, it would never have been pious or puritanical as Spengler uses those terms. Interest in the ancient mystery cults, in the possibility of encounters with alien beings, or in telepathic contact via the psychically attuned with the spiritual dimensions would signify, as Spengler intuited, a need to escape from the weightiness and implacability of a materialistic milieu. The new type of esoterica is mildly dissentient. The Zoology Department tells people that no such creature as Sasquatch exists, whereupon the Bigfoot literature thumbs its nose at departmental dogmatism. The Air Force tells people that the flying saucers have no reality, whereupon the “Close Encounters” literature sends a raspberry at the starched uniforms. In this way, the weird diversions reveal a perhaps unexpected healthy streak. They are anti-pious and anti-puritanical. If the weird diversions were unserious, they would nevertheless be playful. They are playful, moreover, in a baroque manner that endows them with a certain qualified attractiveness. The book with which the Occult Wave began – Morning of the Magicians by Louis Pauwels and Jacques Bergier (French original 1962; first English version 1963) – is self-consciously ludicrous, from its mish-mash organization to its joyous embrace of the most outrageous and unlikely notions. The authors have discerned a stern system, which they playfully oppose: “The Positivists, in the name of Truth and Reality, reject everything en bloc: X-rays, ectoplasms, atoms, spirits of the dead, the fourth phase of matter, and the idea of there being inhabitants on Mars.” Holroyd’s Elements contains a summation of Manichaeism that relates to Pauwels’ jibe at Positivism. Speculating why, with its elaborate and worldwide organization, the Manichaean Church failed to secure a place in the world, Holroyd concludes that it qualified itself as “generally too uncompromising and demanding – in a word too gnostic – to furnish the foundation for a faith of universal and lasting appeal.”

IV. Pagels’ Neo-Gnosticism corresponds, on the other hand, not to Spengler’s religious frivolity, but to his second religiousness. One visited the same so-called metaphysical bookstore to purchase either Holroyd’s Elements or Pagels’ Gnostic Gospels, but the two books differ from one another, one curious but reserved, the other zealously affirmative; in the same way Holroyd’s oeuvre differs from Pagels’ oeuvre – the former eclectic and the latter focused on one thing repetitively. But then Holroyd lived independently, having established a language-instruction franchise. Pagels joined herself to the bureaucracy of scholarship in colleges and universities where an infinitesimal specialization, difficult to distinguish from a general ignorance, defines status. There is something inhuman in the bureaucratization of knowledge. There is something essentially corporate, and thus also essentially inhuman, in a bureaucratized society where human beings become “resources.” What have these phenomena to do with piety and puritanism? Spengler asserts that the second religiousness mimics the “springtime” religiousness of the culture, but it also participates in the crude materialism and the fossilized rationalism of the global regime, the Imperium whether Roman or American. The need to mimic the original outburst of the culture with its panorama of symbols suggests both a lack of creativity and an impoverishment of consciousness. Because the decreased consciousness cannot deal with the richness and variety of the original symbols, it drastically minimizes their number and allegorizes them politically; at the same time it arranges the diminished remainder into a Manichaean dichotomy.

That Pagels should have linked the ancient Gnosticism with the modern progressive agenda well accords itself with the hypothesis that a stark dualism looming up from the past will appeal to the second religiousness. Pagels’ foreword to her translation and commentary on the Gnostic Gospel of Judas, written in collaboration with Karen King, supplies an instance. “At our first reading,” the co-authors record, “the author of The Gospel of Judas struck us as a very angry man with an offensive, even hateful, message, for he portrays Jesus repeatedly mocking his disciples and charging them with committing all kinds of sins and impurities in his name.” According to Pagels and King, “It seemed to us that the author was doing exactly that himself – using Jesus’ name to propagate his own homophobic and anti-Jewish views.” Once the two scholars recognized the document’s radically anti-Nicene character, however, they accommodated themselves to it: “We found that not all is angry”; and that “much of The Gospel of Judas is filled with Jesus’s brilliant teaching about the spiritual life.” A retrojected oppositionality, as the contemporary academic jargon would no doubt have it, permits Pagels and King to overcome their loathing of the “homophobic,” a word whose presence in the discourse betrays (pardoning the expression) the predictable orthodoxy of the two liberal professors.

Pagels can claim something of a successor in Marianne Williamson, a corporate motivational speaker, author of numerous books on spirituality, and in late 2019 one of the Democratic Party candidates for the presidential nomination in 2020. In February 2017 Williamson sat for an interview with The Bodhi Tree, a former brick-and-mortar bookstore of the metaphysical variety, as previously mentioned, and located in Hollywood, which migrated online at the beginning of the teens. Asked about her relation to Christianity, Williamson responded that: “There is a mystical tradition within Christianity, as there is a mystical tradition within Judaism and all the other great religions… The depths are there in Christianity, because the early Christians – the Gnostics – said it all.” Borrowings from Gnosticism permeate Williamson’s prose, which in its repetitiveness and sentimentality resembles that of a Hallmark Card. Human beings incorporate an “inner light” that corresponds to the Valentinian “spark.” To activate that inner light, one must undertake an elaborate self-initiation (the “Course in Miracles”). In the Bodhi Tree interview, Williamson remarks how: “This world of Maya is illusion… You don’t even try to work within the illusion – you transcend it.” Elsewhere: “The Zen mind is very much what the Course in Miracles is talking about, or what in Christic-philosophical terms is known as ‘being as a little child.’” Williamson’s “illusion” is the equivalent of the “botched creation.” Her metaphor of “being as a little child” inadvertently points to the diminished consciousness of her brand of theosophical gnosis, which her simplistic prose likewise indicates. Williamson is undoubtedly the first self-declared Gnostic to seek the presidency of the United States of America.[iii]

Holroyd’s work has disappeared into oblivion. Such a fate befell him ill-deserved but was probably unavoidable given the copiousness of modern publishing and the sub-literacy of the modern reading taste. A reexamination of that work has nevertheless provided the occasion to draw together some seemingly disparate strands of cultural phenomena of recent decades and to comment not only on their relation to one another but also on their genetic relevance to the present moment. In particular, Holroyd’s subtle self-reflection, revealing itself in Flight and Contraries, enables a reader to form the picture, in detail, of what might be called an optimal model of worldly reconciliation and centeredness. In Flight, Part V, in the chapter entitled “Darkness and Light,” Holroyd charts his progress from an alienating and egocentric world-rejection, which at low moments resembled that of the “Angries,” to a Christianizing sense of dwelling in world whose basic goodness he no longer doubts – combined with a complementary sense of standing perpetually under the sign of what he freely names as “grace.” Moving towards a “point of balance,” Holroyd can already participate in that balance although not completely, and perhaps never completely. Holroyd writes: “I am no longer apart; I am a part; and I derive my meaning from the Whole.” The motion occurs “within God.” This progress is the equivalent of Holroyd’s “pursuit of meaning,” a quest that necessarily remains open and that gradually transforms itself into the path of transcendence. The quality of subtlety should be stressed. The questing attitude “embraces things that are irreconcilable and allows itself to be conditioned by… the conflict between them.” Holroyd adds that the “most characteristic expression of [this attitude] is in the form of irony and paradox.”

This metamorphosis in the disposition of the ego has at its beginning and in its consummation stark polarities. Yet Holroyd denies any “dramatic story of ‘conversion.’” Rather, as he writes, “the change was gradual rather than cataclysmic and more in the nature of an awakening than an apocalypse.” Holroyd’s transformation might justly be described as increase of knowing luminosity in the temporal flow of his self-consciousness. Recalling his phase of flight Holroyd tells how “walking in a large city, I felt more my community with the people of the backstreets than with those of the busy thoroughfares.” Despite this, as he writes, “I felt that my natural habitat was the city.” The world struck him as “malignant.” A conviction of “unreasoned pride” accompanied these sensations. In the phase of pursuit, however, “everything is reversed.” He now finds his home in the countryside, where the environment “correlate[s] with my inward condition.” Thus the metamorphosis in the disposition of the ego entails the sublimation of that ego. For the raw ego, life furnished only a scene for monologue. After the transformation, and in consonance with the movement towards transcendence that never completes itself, but that like Grace constantly vivifies, dialogue assumes a supreme importance.

The increasingly homogeneous mentality of the West, ever propagated and ever reinforced by broadcasting and the new digital technologies takes it as a given that the world, although purely accidental and malleable according to whim, exists mainly to provide a platform for egocentric monologue. A neurotic flicka haranguing the United Nations General Assembly represents the trend in an iconic way. Although “progress” functions as a shibboleth for the “woke,” the signs point to regress and to sleepwalking – to a fatal restriction of consciousness that gives no evidence of participating in vastness and permanence and slow rhythms of change. Such a consciousness, insofar as the word consciousness finds justification in context, rejects dialogue. It seems also unaffected by wonder, in which, according to Aristotle, the quest for knowledge, eventually articulating itself as philosophy, finds its ground. In Gnostic fashion, the modern ersatz consciousness claims to possess wisdom or if not wisdom then some kind of diktat from out of the blue to which everyone must conform his thought and behavior. In the apocalypse of modernity, transcendence becomes subscendence, appearing even as human offal on the sidewalks of the megalopoleis. The trinity of vastness and permanence and slow rhythms of change has another name, with which Holroyd, subduing his ego, familiarized himself. That name, which modernity seeks with Ivan-Karamazovian anger to banish from all vocabularies, is – God.

Notes

[i] An actual (if “actual” were the word) “metaphysical bookstore” would be intelligible, but not tangible. It is not certain how the proprietor would make change. Two such businesses nevertheless established themselves under that generic moniker in Santa Monica in the 1980s during the time when I worked toward my doctorate in Comparative Literature at nearby UCLA and lived in West Los Angeles. Phoenix Books was located in the downtown of Santa Monica, the Dawn Horse on Wilshire Boulevard near the West La-La Land demarcation. If memory serve, the Phoenix announced itself in its display-window lettering as a “metaphysical bookstore,” while offering a wide variety of theological, philosophical, ufological, and other types of books. The Dawn Horse specialized more narrowly in occult and spiritualist literature. Neither survived the Internet’s massacre of independent booksellers beginning in the late 1990s. When Colin Wilson came to Southern California on a lecture tour in 1987, he made an appearance at the Dawn Horse one Thursday morning to sign books. I met him there on that occasion when he kindly autographed my copy of Necessary Doubt. Robert Anton Wilson, author of the Illuminatus trilogy, frequented the Dawn Horse and might be encountered browsing the shelves. I acquired any number of books by Wilson, Holroyd, Geoffrey Ashe, and John Michell at these establishments.

[ii] Spengler writes (same context as above): “About 312 [BC] poetical scholars of the Callimachus type in Alexandria invented the Serapis-cult and provided it with an elaborate legend. The Isis-cult in Republican Rome was something very different both from the emperor-worship that succeeded it and from the deeply earnest Isis-religion of Egypt; it was a religious pastime of the society, which at times provoked public ridicule and at times led to public scandal and the closing of the cult-centers. The Chaldean astrology was in those days a fashion, very far removed from the Classical belief in oracles and from the Magian faith in the might of the hour. It was ‘relaxation,’ a ‘let’s pretend.’ And over and above this, there were numberless charlatans and fake prophets who toured the towns and sought with their pretentious rites to persuade the half-educated into a renewed interest in religion. Correspondingly, we have in the European-American world of today the occultist and theosophist fraud, the American Christian Science, the untrue Buddhism of drawing-rooms, the religious arts-and-crafts business (brisker in Germany than even in England) that caters for groups and cults of Gothic or Late Classical or Taoist sentiment. Everywhere it is just a toying with myths that no one really believes, a tasting of cults that it is hoped might fill the inner void.” Spengler formed these thoughts in the early 1920s, but his description is just as relevant to the renewed religious frivolity of the 1970s.

[iii] The worldwide Left has, in the Twenty-First Century, assumed a tone increasingly religiose. The religiosity of the global warming movement, which now stylizes itself as the climate-change movement, is obvious to critical observers. It corresponds to the cultic trademarks catalogued by Leon Festinger, Henry Riecken, and Stanley Schachter in their classic study of a UFO coven in When Prophecy Fails (1956), the foremost trait being that when, as the title suggests, prophecy fails – the cultists cling even more tightly to their beliefs, postponing the judgment day and issuing baroque explanations of why it never occurred on the predicted date. In American politics, the raft of Democratic Party candidates for the presidential nomination in 2020 includes not only Marianne Williamson but also Mayor “Pete” Buttigieg of South Bend, Indiana, who makes religious pronouncements. Many of these combine his professed religiosity with the palaver of the climate-change cult. A Newsweek article (Tue, Oct 22, 2019) quotes him as saying: “Look, I’m not out to impose my faith on anybody else, but to me environmental stewardship isn’t just about taking care of the planet, it’s about taking care of our neighbor, we’re supposed to love our neighbor as ourselves. The biggest problem with climate change isn’t that it’s going to just hurt the planet. I mean in some shape, way or form the planet is still going to be here, it’s that we are hurting people. People who are alive right now and people who will be born in the future.” The “Green New Deal,” however, which Buttigieg supports, and which assumes the “settled science” of the global warming hypothesis, would impose a drastic change of life on Americans.