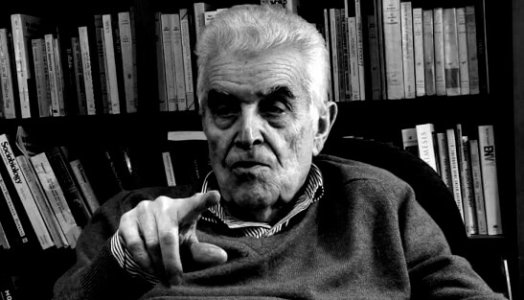

René Girard – Imitation and Life Without God

In preparation for teaching a literature course in the 1950s, René Girard reread some of the classic novels. In the process, he realized that the novelists had had profound insights into aspects of the human condition and that to a large degree, they were the same insights. Not only that: they all ended the same way, with the despised central protagonist recognized by the author, finally, as an aspect of himself. Gustav Flaubert, for instance, commented about the heroine of Madame Bovary, whose delusions he had spent the novel describing and lambasting, “C’est moi.” Cervantes also spends his time having Don Quixote be repeatedly beaten up and humiliated for his stupidities, but, in the end, has Don Quixote recognize and renounce his errors on his deathbed in a way that forgives his protagonist and accepts him. Thus, all the great novels end with a moment of transcendent self-revelation. This claim is certainly immensely provocative and intriguing.

Girard began his exploration of these novelistic insights in Deceit, Desire and the Novel.¹ The key insight is the role of imitation in human life. Mimesis accounts for the unparalleled human ability to learn; to speak a language, and thus to think linguistically, to read, scuba dive, observe social practices, cook, and just about everything else associated with humanity. However, Girard claims, when imitating others is combined with a belief that God is dead, an idea that started to gain some kind of ascendency among intellectuals in the nineteenth century in particular, the thwarted desire for the transcendent takes a nasty turn. What is the transcendent? It is God, heaven, perfection, eternal life, Plato’s Forms, salvation, ultimate reality, enlightenment and supreme happiness. It is spiritual reality associated with the human interior as described in Plato’s Cave. It is subjectivity, interiority, and linked to creativity, imagination, and intuition; as opposed to the realm of the objective, external, and the measurable.

Human beings are intrinsically transcendence seeking creatures. If God is removed as the proper object of worship, as it has commonly been observed, we will find something else to revere. The usual candidates are science, progress, social justice, environmentalism, etc. The human existential position is in the space between animals and God, the metaxy; – something traditionally captured in the notion of the Great Chain of Being. Once God is removed from this scheme, humans have a tendency to fluctuate wildly between self-hatred; claiming to be nothing more than naked apes, comparable to all other primates, and self-deification; imagining, for instance, that we have the God-like ability to create consciousness by replicating qualities of the brain.

Once God is denied, people do not simply abandon their religious tendencies, they merely find substitutes. They attribute God’s properties to themselves or others, they seek to create heaven on earth to replace the actual heaven. Vertical transcendence; desiring God “up there” with us “here below” is replaced by horizontal transcendence. This is a failed non-transcendence where our fellow persons are imagined to have God-like qualities. The most well-known and obvious examples of this are attributing divine qualities to the “Great Leader,” such as Hitler, Stalin, and Mao Zedong – all with giant, greater than life-sized banners depicting them for the mob to worship. René Girard highlights the ways in which the loss of God results in an imaginary divination of even our ordinary neighbors, with misery-inducing results.

St. Augustine had a related insight about the order-producing qualities of faith in God. Augustine claimed that objects, people and money are all good and desirable. They can all contribute to happiness. However, it is necessary not to try to extract more happiness from these items than they can deliver. Human greed exists because human desire knows no limit. Having money, we want more. Possessing objects, we keep adding to their number. We look to other people to provide complete spiritual fulfillment and satisfy our deepest desires – God substitutes. But, our infinite desires function as a bottomless pit. We throw money, objects, and people into it without ever filling it up.

Augustine argues that the only way for infinite desires to be satisfied is to find a suitably infinite object of these desires. Only God matches this description. Once a person looks to God for his spiritual fulfillment, only then is he capable of moderating his desire for objects, money and people.

Augustine adds that while infinite desire can seem like a curse, because it can result in greed, it is actually a connection with God; with the infinite. It forces people to keep searching until the main object of desire is found; rejecting all substitutes. Girard’s analysis finds other pathological consequences of an absent God.

Feuerbach

Karl Marx claimed that he took Hegel and stood him on his head. Instead of history being the progress of Absolute Spirit towards its true nature, freedom, Marx claimed that history is about the progress of man’s freedom here on Earth. Marx said that to reach his philosophy he had to cross the fiery brook – the translation of Feuerbach’s name. Feuerbach claimed that there is no God. God is just a projection of man’s best qualities on to an imaginary being. That then leaves man with all the remaining bad qualities. What needs to be done, Feuerbach argued, is to reclaim the good qualities that belong to man to realize his true human dignity, instead of groveling to an imaginary deity. “In the consciousness of the infinite, the conscious subject has for his object the infinity of his own nature.” This paves the way for Marx’s utopian fantasies and the great piles of corpses, police states, surveillance culture, and economic ruin, that have resulted.

The good qualities will include benevolence, justice, wisdom, and most significantly for Girard’s thesis, autonomy – “God alone is the being who acts of himself.” For Feuerbach, even omnipotence, omniscience and ultimate goodness seem to be qualities human beings are capable of attaining – unlimited physical, moral and intellectual capacities. This confirms the thesis that the death of God results in self-deification on the one hand, with no acknowledgement of human limits, while passing over the other tendency; the self-contempt, self-hatred, of describing humans as apes and animals.

The Enlightenment and the Romantics

The Enlightenment figures imagined that human and social progress would be possible if a strongly rational and scientific approach to life was taken. With the help of science, superstitions like the belief in God, belonging to the childhood of mankind, would be abolished and society could be reformed in a top-down manner, following a rational pattern. Many Enlightenment figures conceived of humans as rational egoists, i.e., smart and immoral. As such, people have no choice but to act in their own self-interests, narrowly conceived. This disgusting and repulsive notion is condemned by the narrator of Dostoevsky’s Notes from Underground, himself a deeply troubled individual caught up in mimetic desire. The narrator describes the Enlightenment image of the compulsorily self-interested individual as a piano key upon which nature presses, and as something he would be willing to avoid by going mad or being completely self-destructive just to assert his own freedom from such compulsion. If the scientists tell him he has no choice but to be self-serving he will do something truly not in in his interests just to prove otherwise; to prove he is a man, and not a piano key.

The Romantics hated this exclusive emphasis on reason and science; leaving out, as it does, feelings, intuition, creativity, and imagination – things central to what it is to be a human being, rather than a piano-key acting under force. It is not that reason and science are wrong, but that they cannot possibly capture what it is to be a person. Love and friendship, for instance, have precious little to do with science and reason. The Romantics felt that feelings and Spirit, an admittedly often rather deracinated Christian God, are central to human existence and wrote some of the most beautiful and inspiring poetry yet devised. They rejected the rational egoist as a picture of man, and replaced it with something far truer, more complete, and profound.

The Romantics were not without faults. Girard points out that from some of the Romantics comes the notion that human greatness is measured by a person’s strength of feeling and by his originality. The idea is that regular people’s feelings and desires are weak, anemic and mimetic – pale copies of what others feel and desire, some of them claimed, whereas the Romantic hero’s feelings are profound and original to him. In this way, the Romantic hero is self-sufficient, bearing the imagined qualities of God. (There are reasons for thinking that even God is not self-sufficient – in order to be Creator, the Created must exist. And in order to make the love of God manifest, something other than God must exist. Though, God’s dependence on us, is quite unlike our dependence on Him. He created us, not the other way around.) In reality, humans are creative, but not like God, because we are incapable of passing on spiritual characteristics to our creations. Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein is a description of a scientist trying to make a human and making only a monster instead. We cannot make something with a soul; with subjectivity; and thus with a spiritual nature – free from an all-pervasive mechanistic determinism. The things we make become part of objective reality, but some of them also become symbols of human creativity and imagination, pointing to the interior spiritual subjectivity of their human creators.

Romantics like Wordsworth and Coleridge were poetic geniuses with a rich concept of the human. But, Lord Byron, for instance, took up lovers en masse, and having ruined their reputations and thus their place in society, abandoned them. He seems to embody the notion that feelings are their own justification and that he is better than the rest of us by feeling more strongly and deeply than others. What the Romantics did not recognize was that feelings are strongest when they are imitated. Girard describes “triangular desire” where C and B both desire A. A is the object of desire. However, when B notices that C wants A, B wants it more. He wants it more because he imitates C’s real or imagined desire for A. C may well have wanted A merely because B wanted it. When C notices that B now wants A more, he also wants A more, imitating B’s new found strength of desire. B notices C’s increased interest, imitates it, and increases his own desire, and so on. This creates an infinite feedback loop, that ramps up desire to unbearable levels. Something similar happens with electronic feedback where a microphone (like the pick ups of guitars) is placed too close to a speaker. The hum or sounds from the speaker are picked up by the microphone and sent back to the speaker via the amplifier. This increases the sound from the speaker which gets picked up by the microphone again, and so on, until an ear-piercing shrieking sound is produced.

Most of our desires are imitated. We want a house, a dog, a spouse, a car, and a college degree, an iPhone, because other people want them. If a student woke up one morning to find that all his fellow students had left college and stopped attending classes, he would too – even if the professors continued to hold class. Tennis players want to win Wimbledon because other tennis players want to win it. The trophy would lose all meaning and all desirability if it were not desired by others. The desire to win is increased by the rival’s desire to win. If someone says something nice about a haircut or item of clothing, this confirms your own good opinion of these things, making you like them even more. Imitating desire puts us in competition with others. Some of our most painfully strong romantic desires occur when we have a rival – real or imagined. Jealousy occurs when our desire for someone increases when we imitate our rival’s desire in this feedback loop. The former boyfriend or girlfriend, for instance, who will not get lost is a thorn in our side, and we can come to imagine that having the beloved all to ourselves will result in some kind of heavenly bliss. We think this is all about A, the object of desire, but our main attention is really on the detested rival, C or B. They fascinate us. In the rivalrous situation, we come to resemble our opponent. This is very hard to admit because we tend to hate our rivals, our antagonists, and being told we resemble this hated person can seem like an insult. They are the last person we want to be told we are like. If the “other side” fights dirty, for instance, in order not to lose, we are likely to decide to fight dirty too, in which case any imagined moral superiority disappears. And in the realm of insults and taking offense, we have a strong tendency to believe that the other person started it when no offense was intended on their part.

Girard points to all the myths and stories involving rivalrous brothers. Brothers bear a family resemblance to each other. The most extreme case is identical twin siblings. The notion of a twin captures perfectly the mimetic quality of competition, brought on by two people desiring the same thing. Because mimesis is intrinsic to the human condition, and because imitating desires can cause violent conflict, many cultures have been deeply suspicious of twins and even killed one or both of them. Girard suggests that the phenomenon of twins is a rather too obvious symbol of agonistic relations. (The “agon” is competition between athletes in Greek, and is directly related to the word “agony,” which is not irrelevant.) Thus, the mythical founders of Rome, for example, were the twin brothers, Romulus and Remus, raised by wolves. They could not agree on where the borders of Rome should be, so, in order to found the city, Romulus kills Remus. The Romans seemed to think this murder was perfectly reasonable and expressed gratitude for Romulus’ fratricidal act. Remus becomes the sacrificial victim, the scapegoat, in this situation – the person of whom it is necessary that he die, while also being someone to whom we can be grateful. His death resolves the conflict and brings the peace and unitary vision necessary for the creation of the city.

Even more famously, there is Cain and Abel from Genesis. They both make sacrifices to God, but God finds only Abel’s animal sacrifices pleasing, while Cain offers vegetables. Both brothers make sacrifices, in all senses of the word, but only one is successful. Cain is jealous and kills his innocent brother. When God asks Cain where his brother is, he answers, disingenuously, “Am I my brother’s keeper?” God punishes Cain by exiling him and permits no one to murder Cain in turn by placing “the mark of Cain” upon him, stopping the mimetic cycle of retribution for killing – where attempts to punish killers are themselves punished as is the case with feuds. All of humanity are the descendants of Cain, not Abel. We are descended from a murderer; someone who got into such a rivalry with his neighbor and brother, that he killed him. This story, originating in Judaism, is one of the first stories where the killing of the scapegoat, Abel, is seen as a crime and immoral – even though without his death, we would not exist. This takes the point of view of victim, rather than the beneficiaries of the crime: us; the mob. The Romans, carelessly, are just grateful to Romulus for killing his rival, while the Jews and later Christians, point out the immorality and sin of Cain. The answer to “Am I my brother’s keeper?” is yes. We are all responsible for each other.

Whether imitation leads to rivalry depends on the nearness of a person’s mimetic model. In the case of Cervantes’ Don Quixote, Don Quixote explicitly admires Amadis of Gaul, his paradigm Knight Errant – a wandering and solitary knight; a purely fictional invention because militarily useless. Girard notes that Don Quixote has given up the human prerogative to choose what he desires, to his hero. This is called “external mediation” by Girard. Amadis of Gaul is the mediator, or model. Don Quixote cannot enter into rivalry with Amadis of Gaul who is fictional. Similarly, a saint imitating Christ does not become Christ’s rival because Christ is too distant. “Internal mediation” occurs when someone’s model is in fact his equal and nearby. Only then can rivalry occur.

Madame Bovary is half Romantic, half not. She desires to feel strongly, but has no ambition to be original. She has been corrupted by tacky romances. She openly admires the remnants of French aristocracy and the high life of Paris. Again, she cannot actually compete. She cannot become an aristocrat because that is something a person is either born into, or not, and she lives a long way from Paris. Her admiration, being explicit, and having models with whom competition cannot occur, still constitutes external mediation.

For Girard, Don Quixote and Madame Bovary are both mad, but they are less mad than contemporary people, because they are aware of and acknowledge their mimesis; copying the desires of others.

The False Promise

According to Girard, modern people, by rejecting the idea of God, put themselves in competition with Him. As with Feuerbach, they seek to obtain God’s abilities and prerogatives for themselves. By demoting God from his transcendental seat, they bring him down to earth, and set Him up as a potential rival via internal mediation. God is imagined to be self-sufficient, autonomous, and original, so moderns claim these capacities for themselves. They rarely openly admit to copying other people; pride does not permit it. But when a person looks within himself, he finds no hint of self-sufficiency, autonomy or originality. What is found is neediness, weakness and ignorance – a nothing; an abyss. People find their own mortality and limitedness. The vaniteux for Girard is the person too vain to acknowledge the role of imitation in his life and so he remains blind to this paramount fact about human existence.

Vertical transcendency means admiring God and divine models. Today, the transcendent is rejected, but the same old tendency to imitate is there along with the same desire for transcendence. But, for many people, there are no gods anymore. Without genuine transcendence, everything is reduced to the same plane of existence. There is no place for our thwarted desire for God to go, but sideways – towards our equals; toward our fellow humans. Girard calls this horizontal transcendency. The more we insist on egalitarianism, on leveling all differences between people, the more people become our rivals. Sameness means competition. Eliminating differences between parents and child, teacher and student, boss and employee, the old and the young, human and animal, ruins hierarchy and thus social structure. In the resulting chaos, everyone rushes for the same things in a war of all against all. With horizontal transcendency, our natural and proper spiritual desires are perverted and directed at other people who are imagined to be god-like.

The doctrine of original sin said that man was fallen and corrupt. He is unable to help himself, but with God’s grace, he may overcome human weakness and become whole. No other human was truly admirable. All were in the same boat. Redemption was sought from God.

Romantic hubris replaces this. Pride suggests God is not needed. Pride encourages the thought “I am self-sufficient.” But then it is found that this is not the case. A person’s self-conception is in fact derived, to a large degree, from the responses elicited from the people around him. People have social needs and a desire to interact. Each person spent years dependent on the exertions and love of his parents.

There is a terrible disjunction between the false promise and reality. Desperately looking around, other people seem to be doing OK. They fit in. It is only I, it seems, who has been excluded from the divine inheritance. I and I alone am the one the fairy godmother overlooked. They all look like they might be self-sufficient and autonomous. Pride turns a person outward. Envious and resentful of what they possess, a person may seek to befriend them. Their being may be sought; we want to be them. The narrator from Notes from Underground writes a letter to the arrogant officer he admires that mixes hatred with a desire to merge with him; “with your brawn and my intelligence, think how great we could be,” he writes.

It is imagined that it is the Other who possesses the divine inheritance. Their being is wanted. But it is not possible to get it; they already have it. They seem to stand at the gates of heaven; both showing us paradise and forbidding entry. They are hated. They are loved; and this is the essence of resentment. It is impossible to be them; they already fill that spot. They are the model, the obstacle and the rival. The desire to get what they have, to be who they are, can turn murderous, as we scapegoat them and blame them for all our troubles.

They, it is imagined, are invited to the feast. I am left out. This is the position of the country man in Kafka’s Before the Law who is prevented from entering the premises of the law by a forbidding looking giant sentry who tells him that if the man should make it past him there is a still more forbidding sentry inside, and one after that ad infinitum. The country man waits there his whole life until old age takes him, having given everything away in his attempt to bribe the sentry. At the last moment a golden light appears through the crack at the bottom of the door which the old man’s dim eyes can barely see just as he dies after hearing that this door was in fact built for him and him alone. That is the tantalizing experience of seemingly having paradise right there; simultaneously proffered and withdrawn.

Pride hides all this. Internal mediation means direct competition with the model. But it is deemed humiliating to have a model and thus not to be godlike; self-sufficient and original. Thus the role of mimetic desire remains hidden. Egalitarianism means that everyone is a potential rival. Vanity turns attention towards the outside to find that which we do not possess; autonomy.

This is the false promise; the promise of godliness. Being excluded from the divine inheritance, a person feels self-hatred. How is it that I alone have been left out? The self-hatred leads to hatred of others; of resentment. Resentment combines hatred and admiration. A person is admired for being seemingly god-like and simultaneously hated for possessing something the other person cannot attain. A sister of mine used to drive a Mercedes. She remembers sitting at the traffic light while pedestrians stared hatefully at her as they stood in the rain. She got so sick of the hatred, she sold the car and bought something cheaper and less conspicuous. But, this hatred would not exist without love. The pedestrian hates my sister because he wants to be her. He wants to be sitting in a beautiful car, while my sister stands cold in the rain. He wishes to change places with her. To take her place. Then she can see how it feels to be left out in the cold! But this is insane. Why would you want to be like someone you despise? The nasty Mercedes driver. Mimesis drives this resentment. I want to be like her. I cannot because she is occupying the position I want. She is an obstacle to getting what I want and as such I hate her. But, I only hate her because I want to be like her. This is ugly, perverse, and self-deceiving. Sometimes, people will complain that the top 1% of people have a disproportionate amount of power and money. (Thanks to the Pareto distribution this is fairly inevitable.) They say they hate the 1% and angrily protest. But, what do they want? They want that power and money for themselves. They love and admire the 1% and want to be just like them. They want to take their place. Their hatred is a lie based on perverted love. This ugly resentment, of which all humans are prone, in this case makes the mob gang together in shared hatred of the scapegoated few.

With original sin and the real God in the heavens, it is at least possible to commiserate with fellow sufferers, and to hope for salvation. We can cry on each other’s shoulders. With the Romantic hero as the model, each person is alone in his imperfection, in his finitude and in his emptiness. In The Possessed (The Devils) by Dostoevsky, one character says men shall be as gods to each other. This is supposed to represent heaven on earth and optimism. Instead, it is the entre to hell.

In The Raw Youth there is a character called Dolgorouki. He is a literal bastard. However, his name is associated with royalty and everyone he meets imagines that he is a prince. The difference between perception and reality is particularly painful to him. Girard says we are all Dolgorouki; a prince to others and a bastard to ourselves.

Snobbery is particularly pathetic. Again, the snob will be transformed, he thinks, by being accepted by his social superiors. Now, this is ridiculous. If someone is truly aristocratic, a person cannot become aristocratic merely by being accepted by them. In an aristocracy, status is conferred by a social rank that can only be changed when a title is inherited due to the death of a relative. Snobbery is only possible where there is actual equality. The social differences are only imaginary. The snob idolizes people who are fundamentally his equals (this goes for all idolization vis-à-vis internal mediation). The more of a snob a person is, the more he condemns it in other people. If someone is great at detecting snobbery, if he understands it, if he gets every nuance, it is because he is a snob himself. The sickest see the sickness in others the best. People attack the attributes found in other people because they possess those attributes ourselves. It is imagined that those qualities can be eradicated by “killing” them in others in the phenomenon called “projection.”

The Neo-Romantic Hero

The Neo-Romantics are more sophisticated. They recognize that it is not possible to prove originality and superiority by the strength of feelings. They realize that feelings are strongest when other people are being copied; when desires are mimetic. But the Neo-Romantics are still after spontaneity, originality, etc.. It is just that the Neo-Romantic hero is he who feels the least. Examples include Roquentin from Nausea by Sartre, or Mersault in The Stranger by Camus. Girard calls this new model the somnambulist hero – sleepwalking his way through life, feeling nothing. This hero knows that all desire is metaphysical, that it is a desire for God. His lack of desire is not explained. Apparently it is spontaneous. A gift from God! Girard contrasts this with the painful ordeal undergone by saints in the quest for self-mastery and renunciation. The saints’ lack of desire is only achieved by self-conquest. The somnambulist hero has undergone no such ordeal, and has demonstrated no such strength of character.

The new hero desires his own nothingness. He sees the abyss inside himself and embraces it. Girard comments that this new model is just another perversion of vertical transcendency. It has just become even more devious. The Neo-Romantic writer pretends he does not care about his reader. He writes horribly with unsympathetic characters. See how little I care? But, he wants to be admired for his lack of desire – he still desires. He turns his back on us, but looks out of the corner of his eye to see if the reader can see how little he cares. Publishing is an embarrassment to him; an admission that he cares. The aristocrats had servants who stole their manuscripts and had them published against their will; an admired writer despite his best intentions. Heaven!

The nihilism of the Neo-Romantic hero

All deviated transcendency (horizontal transcendency) tends toward death. When the desire to be accepted or loved is rejected, this confirms the assessment that the Other is God. The supplicant is not worthy to gather the crumbs from under the adored one’s table. Her rejection proves this. That means there is a tendency to be attracted to all that frustrates; to all that rejects. Proust’s characters are obsessed by women who want nothing to do with them. Proust’s snob wants to be accepted by his social betters; where his wealth, charm, and intelligence are useless. His characters are drawn to stupid young women who are unable to appreciate what he has to offer.

To be attracted to the insensitive is to be attracted to things, inanimate objects, machines. Dead things fascinate because they seem to look into souls and see the truth; this person is not worthy; this person is excluded from the divine inheritance. In worshipping stupidity and insensitivity death is admired because nothing is more insensitive than the dead, the inanimate. A rock seems self-satisfied, desiring nothing and thus is the perfect model.

Sadomasochism

The false promise of godliness leads to sadomasochism. The admired one is the sadist; the admirer, the masochist. It is mere chance which role someone assumes. He who desires first loses in this pathological game of love. This is because both the sadist and the masochist are filled with self-hatred for not being divine. Self-contempt leads to contempt for the admirer. The beloved knows what she is like. To admire her, is to truly be a fool. Yet, the inevitable rejection makes the beloved even more divine-seeming. The more attracted, the more desirous, the more firmly the lover is rejected. “Get away from me you pathetic worm. I don’t want to join a club that will have me for a member.” For the lover, the masochist, the beloved, the sadist, can see right through him. She sees his pathetic ungodliness. The masochist imagines he is being rejected for being unworthy because ungodly. The sadist knows she is not godlike either, but a pathetic worm. An admirer of pathetic worms must be even worse still, so she pours on the contempt. This ability to see his true nature makes the masochist love the sadist even more. Some people fall almost exclusively for unavailable men. They might be unavailable because they are gay, or decades younger. This tendency is self-destructive and based on self-hatred – not liking anyone who likes you.

This pathological dynamic, of sadist and masochist, only arises when both parties hate themselves. Without self-hatred, the beloved will not reject anyone who loves her, and the lover will not become fascinated by someone who rejects him. He will just move on. After all, he is clearly barking up the wrong tree and should go about trying to find someone who likes him. When the self-hating masochist instead becomes even more drawn to the person rejecting him, his pathetic clinginess and craven lack of self-respect will be unattractive to almost anyone. Do not plead when someone does not return your love!

Kirillov: the Apogee

In Dostoevsky’s The Possessed (AKA, The Devils) one fascinating chapter concerns the character Kirillov. He knows that the biggest drawing card of religion is the promise of immortality. If immortality is a lie, then Christianity and all other religion is evil. It must be stopped. Kirillov plans to be a literal Anti-Christ. He will save humanity from its fear of death and by doing so, he will rob God of His power. The notion of God, real or not, will lose its attraction. Kirillov plans to start a new era for mankind by killing himself, but not in fear. Instead of running away from mankind’s nothingness and racing to embrace the Other, he will embrace his own nothingness; his finitude. In imitation of Kirillov, people will learn to love their weakest point, their mortality. By willingly and fearlessly killing himself, Kirillov will save man from immortality and bequeath eternal death; the exact opposite of Christ. Ironically in this misguided desire, Kirillov is more saintly, more of a true believer, than most theists. In death, people will find freedom.

In wanting death, Kirillov rejects God. But seeking to supplant God is effectively to wish to be God; to take His place. Kirillov is God’s rival. If God is the rival, then He is the mediator. Kirillov is imitating God after all, which of course is what is happening when he imitates Christ. The closer he gets to death, the closer he gets to God, to his model and mediator – the exact opposite of his intentions. But the mediator is also the obstacle, so divinity is denied him.

If he ends by killing himself it is in scorn of himself and hatred of his finiteness, like other men. His suicide is an ordinary suicide. In Kirillov the oscillation between pride and shame, those two polarities of the underground consciousness, is constantly present, but in him it is reduced to a single movement of extraordinary amplitude. Thus Kirillov is the supreme victim of metaphysical desire.²

Kirillov is trying to put an end to vertical desires but in the process he demonstrates the supreme deviated transcendency and the most ludicrous. He is attempting to steal God’s actual divinity in the ultimate act of pride and thus shame at his own inadequacy. He wants God’s infinity because he despises his own finitude.

Like all proud people he covets Another’s divinity and he becomes the diabolic rival of Christ. In this supreme desire the analogies between vertical and deviated transcendency are clearer than ever.³

Kirillov is reminiscent of certain famous atheist proselytizers – more fascinated by God than most believers.

The crucial fact of human existence is mimetic nature. The main choice is to choose what and whom to imitate. Will it be an earthly or a divine model? What is not possible is to quell the desire for transcendence. This desire will find another outlet and seek an alternative – it will not simply cease. Once a transcendent heaven is abolished, the tendency is to try to create heaven on earth. This is precisely what many nineteenth century thinkers were hoping for. Unfortunately, since human beings are imperfect, attempts to squeeze them into perfection have led to mass murder and misery, and ever thus it will be.

Notes

21. René Girard, Deceit, Desire and the Novel (John Hopkins University Press, 1976).

2. Ibid. p. 227.

3. Ibid.

This was originally published with the same title in SydneyTrads.