Taleb and Business Ethics

Many of this semester’s readings will be taken from Antifragile by Nassim Nicholas Taleb. He first rose to fame with his 2007 book Black Swan, the title of which refers to rare events. Northern hemisphere inhabitants took the whiteness of swans as a key defining feature of them, only to discover that New Zealand and Australia are home to black swans – a thoroughly unexpected and unpredicted eventuality. Black Swan outlines many of the ways our modes of thinking simply break down and fail when it comes to rare events – in attempting to predict them, in efforts to explain them after the fact, and finally, in trying to plan for them in the future in order to mitigate their worst affects.

Taleb has made a lot of his money by noticing when markets are fragile and betting against them. He became financially independent – meaning he made enough money to live on for the rest of his life – due to the market crash in 1987. He also made money from the drop in the Nasdaq in 2000, and he was one of the few people warning of the likelihood of the real estate crash in 2008, a black swan (there had never been such a crash before), and made money by shorting the market (betting against it). All this has added to his general credibility and gave credence to his criticisms of the financial world’s failings on the topic of risk. One of Taleb’s principles is to have “skin in the game;” meaning, putting his money where his mouth is. If he says the market will go down, he withdraws his money, or shorts the market and, if he claims the market will rise, he invests his money, and goes long on the market. On the big negative events, he has been right. He would like all people, as a matter of ethics, giving advice or making market predictions, to follow suit and to play with their own money. Otherwise, it is just empty talk. Those who go bust, can safely be ignored in the future.

Taleb has an MBA, is a former options trader and risk analyst, and is a mathematical statistician. He is friends with Nobel Prize winners and eminent scientists like Benoit Mandelbrot, famous for his work on fractals. He has a big ego and does not sugarcoat his criticisms of those he thinks jeopardize the economy and ruin people’s lives by making the economy more fragile, and by those who make incorrect financial predictions. These erroneous predictions cost people money when they subsequently rely upon these forecasts. Worst of all, is that the false predictors pay no vocational or financial penalty for being wrong. This topic and its ramifications are discussed at length in the book.

Business schools teach many things their professors know to be false. They do this in order to retain “accreditation.” Accreditation is necessary for those schools, and students attending those schools, to receive various forms of state and federal support. This is motivated by the understandable desire to stop unqualified persons and nonsense institutions from offering “business” degrees and scamming the government and thus defrauding the taxpayers. Unfortunately, the consequence is that business schools end up lying to their students and misleading them in order to stay open. This course will expose some of these lies so that business students have a better idea about what is true and what is false. This is particularly important in the area of financial advice, which is something that those trained in accounting might become involved with at some point in their career. It is immoral, for instance, to, in particular, give elderly people financial advice based on lies. If they lose all their money, they are unable to earn it back, as they are no longer being employed.

Part of the problem is that business school professors are not trained in science and mathematics. As such, they are prone to being fooled by graphs and statistics. It is just not their area. But, as just mentioned, they often teach subjects like “risk assessment,” and they teach the employment of various mathematical “models” used to try to predict the stock market, even when they know they do not work, simply because those models are in fact used by the financial industry and “risk assessor” is an actual job for which business schools are supposed to train students.

Concerning these models, after Taleb has categorically proven that they do not work, he has had people come up to him and claim, “Yes, they don’t work. But they are better than nothing!” Taleb’s reaction is incredulity. Following a model you know does not work, is more foolish and worse than not following such a model. If someone claimed that having a parachute that does not work is better than not having a parachute, that person is wrong. Having a parachute that does not work will give someone flying a false sense of security (at least I have a parachute!) causing him to act in even riskier ways. He may feel calmer and safer, which might be nice, but someone should only feel as calm and safe as the situation warrants. Feeling calm and safe when faced with a lion, for instance, is pathological. Someone who is wearing a parachute he thinks functions is more likely to board a plane he would not otherwise risk flying in.

There is a recently retired professor of engineering at Queens University, Canada whose field was “turbulence,” which exists at the border of chaos and order, and involves very complicated mathematics and computer modeling. He has a strong hatred for Taleb’s writings. When asked why, he explained that he found Taleb arrogant. Taleb is arrogant. However, this ad hominem attack on the person, is absolutely irrelevant to Taleb’s arguments. Arguments, which involve premises used to support conclusions, do not depend in any way on the character of the arguer. Whether someone is morally admirable or not is irrelevant to evidence. Evidence stands or falls on its own. Most importantly, he found Taleb’s arrogance unwarranted. Most tellingly, and what should be of extreme interest to business students of all stripes, is that he found Taleb’s criticisms so painfully obvious that the professor felt Taleb should receive absolutely no credit for making them. The professor stated that the mathematical models used by those in the business world are being completely misemployed and that fact is obvious to any idiot. The trouble is, the professor’s definition of “idiot” in this context is someone with a thorough grounding in advanced mathematics, statistics, probability theory, and physics – the bread and butter of engineers – and it would have to be someone who was also familiar with the world of finance.

Taleb’s innovation is to combine the expertise of the typical engineer with experience in and intimate knowledge of financial markets. Most engineers will know nothing about the stock market nor what goes on in business schools, and most business students know nothing about engineering. Innovation and creativity are often the product of someone coming in from the outside with a new perspective. This is not quite the case with Taleb, since he started out as an options trader, but he studied mathematical statistics for the pure love of it and earned advanced degrees in it, and that is what made the misuse of statistics in the financial markets so clear to him. He also discovered while working as an options trader that traders do not use the heuristics taught by business schools; at least only newbies who do not know what they are doing do that. And such people risk blowing up as a result. Traders have their own non-theoretical ad hoc rules of thumb, that work better than these business school “systems.” Business schools have come in after the fact and tried to systematize what the traders are actually doing – not particularly successfully. The engineering professor feels that he could have pointed out the same misuse of mathematics and statistics, since Taleb’s points are, to him, painfully obviously true – except the professor has no interest in nor expertise in financial matters; which means he could not have contributed in this way. It also seems strange to hate someone with whom you vociferously agree. It seems mostly a matter of resentment, jealousy, and matter different ideas about style.

As Taleb points out, there is no such thing as a generic “expert.” People, if they are expert in anything, are expert in some fairly narrow domain. And we are only truly competent to judge things in those domains. As a philosopher, I frequently come across biologists trying to discuss ethics, or neuroscientists attempting to make definitive statements about consciousness, and I frequently feel like rolling my eyes. I cannot assess their biological claims, nor their specific neuroscience assertions, but once they step into philosophical areas, specifically, ethics and consciousness, they trip over their own feet and contradict themselves. Neuroscientists will even confuse cause and effect. One of them claimed, for instance, that we like helping people because our pleasure centers light up when we help people (at least some of the time.) But, of course, our pleasure centers get activated because we enjoy helping people. The pleasure center being activated is the effect of doing an enjoyable activity. The activity is the cause. If I find what someone is saying in conversation to me interesting, I might derive some pleasure from this. But, I do not find it interesting because my pleasure center is activated. It is the other way around. My pleasure center lights up, if at all, because I find it interesting. The neuroscientist is predisposed to thinking in terms of bottom-up causation (the physical causing the mental) and sometimes cannot wrap his mind around top-down causation (the mind affecting the brain). Since his colleagues are likely to suffer from the same problem, he does not get corrected.

An example of an expert in one field coming in and bringing insights to another field occurred with one of Taleb’s friends, Daniel Kahneman, winner of the Nobel Prize in economics, and author of Thinking Fast and Slow, his most famous book. Kahneman’s real area of knowledge is social psychology, specifically organizational behavior. His collaborator Tarsky would have been joint winner, but Tarsky had died already. After he won the Nobel Prize, Kahneman was invited to address a firm specializing in investing in the stock market; an anecdote he relates in Thinking Fast and Slow. When invited, Kahneman replied that he had no real knowledge of economics, not being an economist, despite his Nobel Prize. The people who invited him said they did not care, they wanted him to come and give a speech anyway.

So, Kahneman decided if he was going to address stock brokers, he had better acquaint himself with their business, so he asked the company whether they would give him a record of every single transaction the firm had undertaken in the last eight years. Kahneman imagined that they would regard this information as secret and say no, instead they provided him with the information. As an expert statistician, he then subjected the data to a thorough analysis. He discovered beyond doubt, proving it mathematically, that the results of the stock brokers’ transactions were no better than chance and were effectively random with regard to outcome. As a consequence, every year some broker or other would be the most “successful” and get some kind of bonus, but, it was someone different each year. One sign that something is the result of chance and is a fluke, rather than the product of skill, is someone’s inability to reliably repeat his success.

Warren Buffett did not make his money by predicting which stocks would go up, and which would go down. He did it by investing in companies that he knew a great deal about personally, and admired the way they were managed, and who was managing them – not by looking into a crystal ball and buying and selling stocks in an effort to get rid of poorly performing stock and betting that some other stock would perform better in the future. Buffett, in the last few years, made a bet that over a ten-year period, an index fund would do better than a highly managed hedge fund. An index fund is one that distributes investments widely in an effort to try to track the market, rising and falling with the market, rather than trying to outperform the market. One advantage of index funds is that they are cheap to manage and so the fees are lower. From any profit made by hedge funds, the relatively high fees of the hedge fund managers must be deducted. Protégé Partners LLC took his bet – with the winner getting a million dollars. The hedge funds were up 22% after nine years, while the index funds were up 85.4%. The final results after ten years remained the same. So, Warren Buffett, the most famous investor who ever lived, is decidedly not a believer in predicting stock behavior.

You would think that the stock brokers would be dismayed; perhaps quit their jobs, or contemplate killing themselves. After all, Kahneman had proved to them conclusively that they were deluding themselves. Instead, they continued to smile and nod as he spoke. Stock brokers had imagined that they were highly skilled. They spent hours each day, and potentially decades of their lives, poring over facts and figures and deciding which stocks to buy and which to sell. It turns out that they might as well have been flipping a coin each time; literally. One thing that should have tipped them off, perhaps, is that each time they decide to buy or sell, some other stockbroker was reaching the opposite conclusion. Genuine “experts” would not disagree over every single decision like that. Buying stocks that are about to go up in price, and selling stocks that are destined to go down in price, is not something that anyone can become expert in. For some things, there just is no relevant data to reach an informed decision. It does not matter how much experience a person has, that experience will not help them predict the future in this way. It is exactly comparable to playing craps (throwing two dice and guessing what number will come up.) Since the result is effectively random, there is no way to predict it. It is a matter of luck and nothing else. It is possible to be right, but not as the result of superior knowledge; just bonne chance. As Kahneman was being driven home after the talk by one of the attendees, the broker said, “Well, I have devoted my life to this firm, and you can’t take that away from me.” And Kahneman thought to himself, “I just did.”

Chaos Theory is an area of science dealing with chaotic phenomena. Included in that category are the weather, the stock market, political events, and inventions. The butterfly effect governs these phenomena. This is where tiny little variations in, for instance, temperature, or wind velocity – a butterfly flapping its wings in Brazil, will, over time amount to enormous differences in the future, such as a hurricane in the Caribbean. The further in the future one tries to foresee, the more these effects build up. That is why the weather remains a mystery beyond just a few days. Even near-term forecasts are frequently wrong. The stock market is influenced by purely subjective things like fear and hope. People merely having an illusory “confidence” increases demand and pushes the price of stocks up. If people run scared, the demand slumps and prices plummet, sometimes based on nothing at all. It can be merely rumor. The weather can affect the stock market; one unpredictable thing affecting another. New inventions like Twitter and Facebook can affect the stock market with unforeseen results. Most major inventions were the results of accidents, which of course cannot be predicted. And, if it were possible to predict future inventions, these predictions would be pretty close to being the inventions themselves. A key part of inventing anything is coming up with the idea. The scientist who invented lasers had no idea about their future applications. His colleagues made fun of him for his fascination with pretty lights. And then political events, which are chaotic, influence the stock market too.

When students are asked “Who has a better chance of predicting whether the stock market will finish up or down at the end of any given day? You or a professional stock broker?” Students almost invariably say the stock broker. They are absolutely wrong. Any random student is equal in ability to the stock broker because predicting the market is not something someone can be an expert in and practice does not improve your performance. Again, the stock market is a random phenomenon. Kahneman proved that stock brokers could not beat chance. In exactly the same way, the professional craps player is no better at predicting the roll of the dice than anyone else. This can be contrasted with poker or blackjack – games that combine luck and skill.

One factor that might make students wish to defer to professional stock brokers is that with activities that are easy, like driving a car, we tend overestimate our abilities. Most people think they are an above average driver – which is mathematically impossible. But when asked to compare ourselves with other people about something difficult like calculus, then our overconfidence disappears and we tend to underestimate our abilities vis-à-vis other people.

Most people are awful at calculus. Maybe the questionnaire should say: “You are terrible at calculus. How terrible do you think you are compared with all the other people who are also terrible at calculus?” You know you are no good at predicting stock prices, so you imagine that an “expert” will be better, but there are no “expert” stock brokers just as there are no expert craps players. Predicting the stock market is not just difficult, it is impossible.

One of the annoying things about stock brokers is that their job is one where they cannot lose their own money; they can only get richer. Stock brokers subtract a fee for their services of buying and selling stocks on your behalf regardless of whether the stocks rise or fall in value. Brokers buy and sell stocks for the common man. A trader buys and sells on behalf of his firm. Traders can get in serious trouble because their firm suffer the consequences of their selling and buying decisions, whereas brokers are protected. A French trader invested $7.2 billion dollars without the knowledge of his superiors and things went horribly wrong. There had to be an investigation into how he had been allowed to invest so much.

From the NYT:

A French bank announced Thursday that it had lost $7.2 billion, not because of complex subprime loans, but the old-fashioned way because a 31-year-old rogue trader made bad bets on stocks and then, in trying to cover up those losses, dug himself deeper into a hole.

Société Générale, one of France’s largest and most respected banks, said an unassuming midlevel employee who made about 100,000 euros ($147,000) a year identified by others as Jérôme Kerviel managed to evade multiple layers of computer controls and audits for as long as a year, stacking up 4.9 billion euros in losses for the bank.

If the risky investment pays off, such a person might be richly rewarded. Periodically, traders will “blow up,” lose everything, and get ejected from the system, never to be employed again.

If any stock broker could consistently predict whether the market would end high or low on any given day, he would quickly become the richest person alive. But, such an ability would also have paradoxical effects on that very market, negating this ability. Once other people realized what was going on, they would watch this broker with eagle-eyed interest. If he sold, we would all sell. If he bought, we would all buy. However, this would mean no one would be buying when we sold, and no one would sell when we wanted to buy. No one could make any money, including the omniscient broker. Even if just the majority followed the mysterious individual, then as soon as he signaled his interest in selling, the price of the stock would drop instantly, and when he wanted to buy, the price would go up, making it impossible for him to profit.

So, the paradox would be that having the ability to consistently make money off the stock market, would make it impossible to have that ability. If you could do it, you could not do it. Being right concerning conditions of luck means always being in the realm of flukes. Hitting a free throw once means nothing. Doing it thirty times out of thirty is skill. With chaotic phenomena, it is all flukes and no skill. Again, it can be asked who has a better chance of predicting end of year employment figures? You or an economist? Neither. If you do not believe this, check the record of economists in making precisely this prediction. Economists do not know what variables may occur that will affect this outcome. You know that you are in no position to guess employment figures, but you might not realize that neither is anyone else. You are just as good as anyone else on this topic – namely absolutely terrible. You have no ability at all to know what the figures will be. The number of times that reporters have said “Contrary to economists’ predictions, employment figures were higher (or lower) than expected” is ridiculous. In fact, it is the norm for this to be the case, which means that paying any attention to economists’ predictions about employment figures is stupid. Do not fall into the trap of saying “But, it’s better than nothing.” It is not better than nothing because it induces a false sense of confidence, thinking you know something when you do not, and any decisions based on this unreliable activity will also be unwarranted. It is epistemologically identical to watching the scratchings of a chicken and saying “If he pecks on the left first, we do plan A, and if he pecks on the right, plan B.” The key thing, as Taleb points out repeatedly, is to check the predictor’s record of success. Economists have no record of success on this topic.

A similar question could be asked about the future of tax law. An accountant who studies tax law has no more data to help him make predictions about the future of tax law than anyone else. It is possible to be an expert about tax law. It is not possible to be an expert on what tax law will be in the future. Politicians make such decisions and they are influenced by public opinion, what they think might benefit their parties and themselves, and which party gains control of the presidency, Senate, or House of Representatives, and then any deals or compromises made between all these entities. A student is likely to think that he is worse than an expert accountant at predicting tax law changes partly because he is very aware that he has no such ability, but neither does anyone else. There are no experts on the future. Studying taxes does not make you clairvoyant about the future. If you disagree, show me the evidence of people who are knowledgeable about taxes consistently making correct predictions.

Taleb’s response to this kind of uncertainty is to employ positive optionality – make bets with big upsides and little downside – a lot to gain, a little to lose, knowing you are making a bet.

Another strange falsehood in economics is homo economicus as a model for the consumer: the perfectly selfish and rational individual making economic decisions based on purely rational estimates of what is in his narrow self-interest.[1]

Nearly all thinking, and certainly theorizing, requires simplification. Thoughts that leave nothing out; that are as complicated as, say, the physical world, would simply reproduce the world one to one. The model of the world would simply duplicate the world. It would be another world of the same size and complexity. However, if the model is too inadequate, like homo economicus, it can make estimates about how people are likely to behave worse than completely untutored intuition based on ordinary experience. The person comes out dumber than if he had learned nothing.

Rationality is restricted to the few. It is estimated only ten percent of Americans would qualify. So, homo economicus would be a rare bird indeed. Secondly, when it comes to buying things, a lot depends on fashion and mimesis (copying other people) which is not a rational reason for buying something – that ties in to the fallacy of popularity. The most popular music, food, clothes, TV programs, cellphones, is not thereby the best.

Thirdly, human beings are not exclusively selfish. Parents love children, children love parents, friends love each other, etc. Complete selfishness would mean the end of humanity. Sociopaths love no one and they are tormented by boredom. Nothing has much point without other people. Even learning things can become pointless, depending on what it is, if it is not possible to share what is learned with others.

Philosophers can take a lot of blame for having influenced the ideas involved in homo economicus. British philosophers in particular tended to love the idea that hedonism, the selfish pursuit of pleasure, is the only driving force in human behavior, since they usually liked “science” and dislike the complexity and frequent mystery of human motivations. They regarded people as a kind of soulless windup doll and wanted as simple an attribution of human interiority as possible. In truth, they would have liked to dispense with it entirely, but they needed some reason for why we ever get up off the couch. The obvious counterexample to the claim of selfish hedonism is all the things we do for other people. The hedonist claims that since all behavior is driven by the pursuit of pleasure, helping other people is due to the fact that people enjoy doing so. Pleasure is the driver. However, the word “selfish” means exclusive concern for one’s own welfare. If someone enjoys helping other people, he is, by definition, not selfish. You have to actually like helping other people to derive any pleasure from it. Claims are only assertions about facts when they could hypothetically be wrong. Only tautologies can never be wrong because they are true by definition – the most famous example being “all bachelors are unmarried men.” There can be no exceptions. The claim that all behavior is driven by pleasure and therefore, in the end, selfish, admits of no possible counterexample. Hence, it is not a claim about the world at all but is supposed to be true by definition. It is not.

There is a regular cottage industry debunking homo economicus. It has made whole careers. Richard Thaler even won a Nobel Prize for challenging it, which seems ridiculous. There is a famous and easy experiment that is well-replicated called “The Ultimatum Game” where someone is offered one hundred dollars. The condition is that he only gets the money if he offers some of the money to another person. If the offer is rejected, neither gets anything. The perfectly rational and selfish point of view about this is supposed to be that the other person should accept any amount, no matter how low. If someone offers you one dollar for nothing, you should accept it. You will be one dollar richer, having done no work. Refusing the money, no matter how little, is irrational. Accept it! However, most people do not behave in this manner. The other person knows that you too are getting the money for free. If they decide you are being too selfish, greedy, and ungenerous, they will typically refuse the offer in order to teach the offerer a moral lesson. The lop-sided offer is regarded as unfair. Typically, anything below about thirty dollars is rejected. This behavior is universally regarded as “irrational” by the people who write about it in the context of the experiment, as though there is something irrational about worrying about fairness. But, this definition of “rational” equates rationality with amorality, which is a very odd thing to do. Since we are social creatures who live in communities and moral considerations govern our interactions with people we depend on, not taking morality into account would be the irrational thing to do. Try it! See how long you last. The fact is that people think in moral categories, and a high percentage of people are willing to forego free money in this context. Chimpanzees who also understand and employ the notion of fairness/reciprocity behave in the same way.[2] People include moral categories in their decision making. Who knew? Everyone other than economists.

Quantifying Risk

Risk assessors who offer quantitative assessments of future risks are charlatans. It is possible to extrapolate from past data when it comes to types of surgeries or types of diseases. It is reasonable to state that there is a 5% fatality rate for a certain kind of surgery, or a 25% survival rate for a particular kind of cancer treatment based on past cases. Of course, these are still broad generalizations. What the patient would really like to know, what are my chances of dying or surviving, is not known. A church-going health-fanatic patient with a very positive attitude, lots of social support, and high compliance to medical instructions, is likely to have a different outcome to someone with the opposite characteristics. But some kind of meaningful numbers can be provided to the patient about patients in general in those circumstances. When it comes to making predictions about the future involving chaotic events, and not things like laws of physics, then there is no data to extrapolate from. There is particularly no meaningful data concerning black swans; one off, or extremely rare events. This is related to the informal fallacy in logic called “hasty generalization.” The world avoided nuclear conflagration after the Cuban Missile Crisis – when there was a nuclear standoff between the USA and the USSR in the early 1960s – therefore the next time there is a standoff between the Russia and the USA, it will end the same way with the same favorable result, is unwarranted. If something has happened hundreds or thousands of times, a meaningful prediction might be possible if the events are not chaotic or random. If something has never happened before then there is nothing on which to base a generalization. Michael Burry, depicted in the movie and described in the book The Big Short about the housing crisis of 2008, consistently shorted (bet against) the housing market. His superiors put more and more pressure on him to stop, because it costs money to short the market. Their argument? The housing market has never failed before therefore it will not fail this time. That is not a reasonable argument. They have no evidence one way or another. Many rare events are one off affairs. By the same logic, 9/11 should not have happened. It had also never happened before. When looking to extrapolate from “data” with black swans, there is no data.

As Taleb argues, when it comes to black swans, “data” of the kind that can be graphed, for instance, is meaningless. What Michael Burry had done was to read thousands of pages of documents concerning how mortgages were being bundled – and they were intentionally bundled in an obfuscatory fashion; mixing reasonable and legitimate mortgages with ones where the mortgagee had almost no chance of paying the loan off. These documents were as interesting to read as the “Terms and Conditions” contracts we all sign to use software and web services – i.e., not at all, so no one else read them. Burry discovered that the housing market at the time was built on a house of cards. That it was fragile – to use Taleb’s term – meaning prone to catastrophic collapse, that is, over-exposed to risk. People who are overly in debt are fragile. If you are in debt, and barely paying off your minimum credit card payments, rent, food, etc. then you are fragile. If you have six months of income saved in case of unemployment, etc., then you are robust. Meaningful risk assessment is about noticing fragility and taking steps to minimize it. You are fragile (over-exposed to risk) if all your stocks are invested in just a few companies. You are less fragile if your risk is spread out relatively evenly across multiple companies and investment types.

A certain podcaster with a background in economics likes to assign percentages to various eventualities. He will say “I estimate that X, this one off event, has a 5% chance of happening,” such as a new American Civil War. This is both meaningless and misleading. Karl Popper, the philosopher of science, stated that a key feature of scientific theories and assertions was “falsifiability.” If an assertion is made that cannot be proven wrong, no matter what, then the assertion is not scientifically valid. When the podcaster makes his “5%” prediction, what data could possibly either confirm or disconfirm his statement? If the event happens, he will say “Well, the event fell within that 5% chance.” If it does not happen, he can say “Well, I said that there was a 95% chance of it not happening.” His prediction is not based on past experience, because the event has never happened before, and it cannot be falsified. Thus, his prediction is meaningless. And where does “5%” figure come from with one-off events in the first place? Could it be 5.5%, 16%, 32.3%? The “risk assessor” is just making the numbers up. The predicted event happening or not happening does not provide information to intelligently and rationally alter the numerical figure. Thus, making quantitative guesses about black swans is not something the risk assessor can get better at. He receives no feedback whether his quantitative analysis was correct or not. It could be compared to shooting free throws in basketball and never finding out whether the ball is going in or not. There is no way to improve. So, there is no data to base the 5% on in the first place, and no data to verify or reject the figure even after the fact. Both problems are terminal.

When trying to predict who will win the US presidency, pundits will say “So-and-so has a 95% chance of winning.” Under what conditions could this prediction be proven wrong? Some such pundits got very upset when people accused them of being wrong when the other candidate won. They said, “You don’t understand how statistics work. When something happens that we said was highly unlikely happens, that does not mean we were wrong. It just means the rare event, the possibility of which we accounted for, happened.” The problem? Their prediction is unfalsifiable because they hedged their bets. They are pretty close to simply contradicting themselves. They say “X will win (and then name an arbitrary percentage), or Y will win” (and then name an arbitrary percentage). With contradictions, you can never be wrong. X wins. See I was right! Y wins. See I was right! This fails Poppers test of falsifiability. The predictor claims to be right either way and there is no way to test the prediction, or even to track the record of the predictor. Effectively, they are not claiming anything meaningful at all. That business about putting a number to likelihood is baloney. Again, it only makes sense when there has been a long history of exactly those kind of events to extrapolate from. When something has never happened before, like a housing crisis, or a particular individual winning the US presidency, then no predictions using quantitative degrees of certainty can be made. But, it is possible to identify and note fragility. Fragility does not tell you when something will happen – which is why Michael Burry had to wait so long – but it does note over-exposure to risk this makes it possible to minimize that exposure. It is helpful, perhaps, not to call this a “prediction.” Burry is not looking into the future. He is looking at over-exposure to risk right now and pointing it out. It is not different in principle from a car mechanic telling you you need to service your brakes. It is about risk, not foretelling the future, though dire consequences of ignoring the advice are likely.

A falsifiable election prediction is “I think X will win.” Or, “I think Y will win.” At least you are not saying X or Y will win. We can then track the record of such predictions. There will, however, still be a high degree of luck involved and it would be unwise to put much at stake on guesses.

We know that making predictions makes people take more risks even when the person knows that the forecast was fictional. Quantifying risk is a prediction. Quantifying something means using mathematical models. Mathematical models work for casino-style gambling because all the variables are known in advance. Casinos only need to “win” 52% of the time to make money and they can determine this with absolute precision. They do not need to predict the outcome of any particular gamble. They just need to know the odds in the long run. Short term losses mean nothing to them. If someone games the system and changes the odds by counting cards, etc., then this becomes a threat and the casino will ban them. Crucially, all casinos who stay in business also put an absolute limit on the size of bets to restrict their losses.

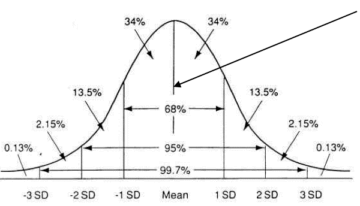

The idea that a good analogy can be made between stock markets and casino gambling Taleb calls the Ludic (game-playing) Fallacy. Casinos determine upper and lower limit to how much money can be won or lost. This makes it amenable to the application of Gaussian bell curves. Human height is nicely distributed in this way; with a mean, and with deviation from the mean being exponentially rare. There are a similar tiny number of five foot men and seven foot men – in fact, seven footers will be even rarer, since 5’9” is the average US male height. But, if this upper limit is thrown out, and someone could be a mile tall, or a 50 billion light years tall, then the bell curve would be inapplicable. Trying to use it would radically underestimate the likelihood of huge deviations from the mean. And the misapplication of bell curves actually happens with black swans. Since black swans live in the “tails” at either extreme of the bell curve, they cannot be distinguished from “noise;” randomness. There are too few data points. What having upper limits does with casino gambling, together with having all the games known in advance with their precise rules of play, and thus knowing all the possible “moves,” is it makes this kind of gambling absolutely calculable and amenable to statistical analysis. The exact odds can be ascertained. In the world of finance, people can come up with brand new things like credit default swaps (in 1994), or whatever.

With stock markets, the variables are not known. The Harvard professors who invented the use of mathematical models for predicting the stock market started a company called LTCM – Long Term Capital Management in the 1990s. The company went bust in 6 months because of unpredicted events in Russia. The professors claimed it was not their fault because the models did not account for those events. It was not because there was something inherently wrong with their models, they said. But, there is something wrong with both. Their models are vulnerable to rare and unpredictable events which cannot be quantified, with potentially catastrophic results. Therefore, no mathematical models can predict the stock market, which is a provably chaotic phenomenon. Saying “But we didn’t know that would happen” does not save you from the conclusion that it is unwise to rely on models that cannot take account of things no one knew were going to happen. People need to know what they do not know. They need to know that they are vulnerable to catastrophic black swans that are impossible to model, and to act accordingly. Thus, it makes sense to take account of fragility, but not to make predictions about such things.

The mathematical models that LTCM used are still being taught in business schools. If they failed the professors who invented them, they will fail you and your clients too. The idea that you will employ them better and more successfully than them is ridiculous.

It is not possible to rely on “worst case scenario” predictions. Every “worst case” that has ever happened had never happened before. Therefore, no one predicted it. You cannot assess how high the Nile will flood from the high-water mark from last time. What percentage of risk would risk assessors have given to 9/11? Upon what evidence and data would they have made that risk assessment? Zero.

The Turkey Problem

The turkey problem is named after Bertrand Russell’s observation that from the point of view of a turkey, the turkey farmer loves him. Every day the farmer feeds him and every day the turkey’s confidence in the farmer’s love grows. The number of data points increases, each instance confirming the turkey’s claim to be loved, at least in the mind of turkey, until the day when the turkey’s expectations proved to be unfounded and he has his head chopped off. Do not be a turkey!

Quantitative analyses are almost necessarily going to suffer from the Turkey Problem. I say the stock market is likely to crash because an area of the economy is fragile. You start checking the data to see if this is true. What you see is no crash 1, no crash 2, no crash 3…etc. I will be wrong, wrong, wrong, wrong. Every time your sample sees no evidence of a crash, you will take this as confirmation that I am wrong. Taleb was wrong, wrong, wrong, about the 1987 stock market crash, until it crashed. He was right just once. Then he was wrong, wrong, wrong, about the early 2000s dip, and wrong, wrong, wrong, about the 2008 housing crisis, and again right just once. The Turkey Problem is very real and very problematic. Taleb was right just four times and wrong countless times, depending on how often outcomes were sampled. The people who bet against Taleb are now poor, or out of the business despite being “right” oh so many times.

1. Bridge example

2. Running into the road without looking

3. Searching for sunken treasure

An engineer notes that a particular bridge is fragile because of age or structural design problems. But, using your quantitative risk assessment models, every car and truck that passes unscathed over that bridge will be taken as evidence that the bridge is safe. This might go on for years. Every time the bridge does not collapse under the weight of a truck or car, this will be taken as evidence that it is perfectly safe. No amount of sampling will reveal the fragility. It is possible to identify fragility, but not to predict when exactly the bridge will collapse; what will be the final straw that breaks the camel’s back. A mother could warn a child to look before entering a busy road. If the child took note of every time he entered the traffic without looking, and tallied the score, he could claim that every instance of entering traffic without looking counted as evidence that it is safe to do so. He would be seemingly “right” countless times while his mother would seem wrong repeatedly. We know that in fact he is exposing himself to risk each time he runs onto the road without looking, and also that a black swan event, one that has never happened before (to this boy), is inevitable. The “evidence” that he is wrong will come too late to save him. The evidence will be his own demise.

When searching for sunken treasure, the treasure hunters will employ a grid over the area they believe the treasure might be. Each time the hunters examine a square of the grid they will come up empty-handed. They will be “wrong.” But actually, because the search is done systematically, each failure is useful information. Assuming the treasure is there at all, the searchers are narrowing down the area that needs to be explored. Instead of a one in twenty chance, as the number of squares reduce, it becomes a one in ten, then, nine, then eight, etc. chance. They will be wrong perhaps nineteen times out of twenty. They need to be right once.

It is worth memorizing the gnomic sounding phrase of Taleb’s, “absence of evidence is not evidence of absence.” The fact that there is no evidence that the child is in danger in this case does not mean the child is not in danger. Again, the evidence of catastrophe comes too late. Alan Greenspan, the former head of the Federal Reserve, was quoted just before the housing market collapse as saying that the chance of a collapse happening was effectively zero. He had falsely been regarded by many as some kind of seer and guru up to that point.

The turkey problem involves misunderstanding exposure to rare bad events. Because of the nature of the economic system, rare events can wipe out all profits made in just one moment. If the economic system was like losing or gaining weight, the increments of change would be small and relatively predictable. Your money would be relatively safe and you would have time to change direction before you lost it all. You could also rely on bell curves. But the economic system exists in Extremistan where a single rare event can destroy all gains.

The result of quantitative risk assessment is to radically underestimate risk. How can you quantify events that you don’t know are going to happen? If you are walking in total darkness near the edge of a cliff, which is better – to know that you do not know where the edge is or to think you know, but to be wrong? What if I do something that makes you more likely to take risks with regard to that cliff? Have I helped you or harmed you? Nassim Nicholas Taleb is sick of business professors and others saying “But these models are all we have. They are better than nothing.” You don’t “have” anything other than a fiction and thinking you have a reliable map when you do not is much worse than knowing you do not know. Trial and error is a method of taking small risks with the expectation of being wrong until the time that you are hopefully right. Trial and error = positive optionality. Small risks mean low downside. Positive optionality is a way of using uncertainty and unpredictability to your advantage. It is immoral, however, to set up a system where you repeat all the possible benefits of instability and uncertainty while leaving the risk with someone else. That is the situation with “too big to fail.”

Notes

[1] Enlightened self-interest is quite different, and means that being all-consumed with “self” is, paradoxically, not in your own best interest. Generous people who care about other people; family, friends, community, nation, do better, generally speaking, than an egocentric oaf.

[2] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3568338/