Teaching the American Political Tradition in a Global Context

Education is the task of crafting the souls of students; it is never simply about conveying information so that students can enlarge their body of knowledge. While education should indeed contribute to a student’s basic knowledge of facts and theories, its goal ultimately, is to cultivate a particular kind of human being.

The political philosopher, Leo Strauss, suggested that education with a liberal focus was an education “in culture or toward culture.” For Strauss, education was not about information sharing, or “indoctrination”, but rather about cultivating beauty and “liberation from vulgarity.”[1] Strauss’s approach to education required much patience, humility, and discipline. A similar view of education can be found in the works of political philosopher Michael Oakeshott. In The Voice of Liberal Learning, for example, Oakeshott argued that education is about “learning to become human;” it is a discipline of mind and heart and a release from all that is slavish and circumstantial.[2]

Both Strauss and Oakeshott understood that education presupposed an understanding of human nature and of the human condition. It required teachers who had an intimate understanding of their pupils and of the culture in which they existed. Education could not ignore the context, in which students lived, the circumstances in which they were maturing, and the society into which they would eventually be released.

Given the calls for internationalizing the American higher education curriculum within American universities and, furthermore, given the existence of globalization and the rapid dissemination of the Internet and Information Communication Technologies (ICTs) in today’s world, it is vital to discuss and assess the impact of these factors upon the teaching of American political traditions. It would appear to be the case that the existence of these factors should have a profound effect on both the content and techniques of teaching American political tradition but, if so, what type of effect should one expect and prepare for?

This chapter provides an assessment of the dynamic interaction between the teaching and learning of the American political tradition in political science curricula and the current context within which this teaching and learning occur. The guiding principle of this assessment is that teaching and learning of the American political tradition within its current 21st century context is a symbiotic two-way process in which both factors are equal contributors. Attempts that solely consider the influence of the current context on the teaching and learning of the American political experience but ignore or overlook the influence of the latter on this context are limited and unproductive.

To consider the symbiotic and dynamic relationship between teaching, learning, and context, this chapter is divided into three interrelated sections. First, consideration is given to the context within which the American political tradition is taught and learned. This context is one that is globalized, digitally interconnected, and populated with Millennials or, in the words of Marc Prensky, Digital Natives.[3] This section is followed with an exploration of the American political tradition and its trans-generational and global character. Lastly, the chapter concludes with possible pedagogical implications and applications of the symbiotic relationship between the teaching and learning of the American political tradition and its current context.

Context Matters: Millennials and Their Interconnected and Cosmopolitan World

What does it mean to argue that today’s students are Millennials or Digital Natives? Prensky suggests that the defining characteristic of such students is the fact that their entire life experience has transpired within the Internet and through digital connectivity.[4] Unlike any other generation in human history, the Internet and ICTs have undoubtedly influenced the development of Millennials. Sweeney has argued that along with a digital culture, the defining trait of Millennials is their “spirited individualism.”[5] What Prensky and Sweeney illustrate is the tendency in academic and popular discussions to provide a taxonomy of Millennials in terms of their sociological and cognitive features. It is essential to note that, usually, the discussion of the sociological and cognitive traits of Millennials is so deeply intertwined with digital technology to the extent that, Millennials and digital technologies are almost always considered synonymous. What this means is that quite often, the lines of demarcation between the Millennials as sentient beings, the technologies they utilize, and the cultures they form are entirely blurred.

In spite of the blurring of distinctions, it is still possible to demarcate two dominant schools of thought concerning the essential attributes of Millennials. Both of these schools of thought consider ICTs such as the Internet to be central to the Net Generation’s existence, however, they differ regarding the effects of ICTs on the cognitive and sociological development of Millennials.

The first school of thought considers Millennials as an enhanced generation. Prensky has argued that digital technologies have precipitated a permanent and positive change in the thinking and learning patterns of digital natives and, consequently, higher education philosophy and pedagogy should be revised to accommodate this reality.[6] Prensky is not alone in this observation. Andy Clark, for example, has argued that the seamless interaction between technology and human thinking has affected the thinking and learning process of human beings to the point that perhaps cyborg – and not human – is a better descriptor and perhaps better condition than the current existential state of humans.[7]

Nick Bostrom of Oxford University’s Future of Humanity Institute, has also argued that information technologies have enhanced the human capacity for cognition and substantively affected and enhanced the thinking process of today’s humans.[8] Those who consider Millennials as enhanced beings suggest that they are more intelligent and demonstrate faster cognitive processing as well as different and alternative thinking patterns. Thus, they can multitask more effectively, process more information more quickly and critically, and, therefore, are bored more easily. This “information-age mindset,” as Frand calls it, means that higher education pedagogy must reorient itself to a new and different kind of student.[9]

The Enhanced Generation school of thought also suggests that Millennials are more deeply connected to society and thus the world, and are more progressive than ever before. In short, Millennials are progressive cosmopolitans at heart. ICTs have certainly assisted in this process. The Internet has facilitated a reorientation of how Millennials understand the world. As Joshua Yates has argued, in commenting on the work of sociologist, Roland Robertson, today’s cosmopolitanism is the result of a globalization that has led people to have a, “growing consciousness of both the world as a single place…and humanity as a single people (italics original).”[10] This growing consciousness is clearly evident in the Millenial generation.

In Millennials Talk Politics: A Study of College Student Political Engagement, a 2007 report of the Center for Information & Research on Civic Learning and Engagement (CIRCLE), at Tufts University, researchers concluded that Millennials volunteer at record numbers and have an intense desire for civic engagement and participation.[11] The Net Generation wants to make the world and its own communities better. They are dissatisfied with any political worldview that is divisive and fragmented preferring social unity and holism. In the more recent New Progressive America: The Millenial Generation report, researchers argue that Millennials “are more oriented toward a multilateral and cooperative foreign policy than their elders”, and that America, “needs to be more connected to the world, rather than have more control over its borders.”[12] For Millennials, cosmopolitanism and localism are not mutually exclusive – it is all one big world and one large people. As Greenberg suggests, Millennials or Generation We are, “smart, well-educated, open-minded…independent…and a caring generation, one that appears ready to put the greater good ahead of individual rewards.”[13]

While the Enhanced Generation School considers Millennials as an upgraded cohort, the Dumb Generation School regards Millennials as a stunted generation. The leading spokesperson for this view is Emory University English professor, Mark Bauerlein. One of Bauerlein’s first salvos appeared in a January 6, 2006 article entitled “A Very Long Disengagement”, published in the review supplement of The Chronicle of Higher Education. Therein, Bauerlein argued that Millennials though highly connected via technology are educationally illiterate.

As Bauerlein wrote:

“We can be certain that they (i.e., Millennials) have mastered the fare that fills their five hours per day with screens — TV, DVD, video games, computers for fun — leaving young adults with extraordinarily precise knowledge of popular music, celebrities, sports, and fashion. But when it comes to the traditional subjects of liberal education, the young mind goes nearly blank.”[14]

Bauerlein’s scathing criticisms were just starting. In May 2008, he published the widely-read and much discussed The Dumbest Generation: How the Digital Age Stupefies Young Americans and Jeopardizes Our Future. Bauerlein agrees that Millennials volunteer more than ever before and have enhanced resources at their disposal. They are technologically rich but intellectually and socially impoverished.

As Bauerlein argues:

“Yes, young Americans are energetic, ambitious, enterprising, and good, but their talents and interests and money thrust them not into books and ideas and history and civics, but into a whole other realms and other consciousness. A different social life and a different mental life have formed among them. Technology has bred it, but the result doesn’t tally with the fulsome descriptions of digital empowerment, global awareness, and virtual communities. Instead of opening young American minds to the stores of civilization and science and politics, technology has contracted their horizon to themselves, to the social scene around them…the more they attend to themselves, the less they remember the past and envision a future.”[15]

Bauerlein’s concerns of a deeply connected and technologically savvy generation that has no intellectual and human depth are echoed by several others. Jackson has convincingly argued that the Internet and Information-Age are making distractions an essential aspect of what it means to be a human being.[16] The qualities necessary for moral growth – patient attention and reflection – may now be passé. Many others have filled the pages of The Chronicle of Higher Education and other publications echoing and adding to the concerns of Bauerlein and Jackson.[17]

As in any debate, there are various arguments that exist in no-man’s land and this is no different in the current debate between the Preskys and Bauerleins of the world.[18] Who, and perhaps what Millennials are, is still an open question and an intensely debated issue. Both The Enhancement and The Dumb Generation schools of thought have, however, delineated the parameters of the discussion and focused discussants on the key themes of educational content and teaching pedagogy. Depending on the school with which one is most sympathetic, content should center on either the future or the past and pedagogy should either be student-centered or content-centered. This is not to suggest that the other pole in the dichotomy is ignored. Rather, it is still acknowledged and considered but only in service to the dominant pole of the dichotomy. American universities and leading American higher education policy groups have for the most part accepted the conclusions of The Enhanced Generation School. It would be odd for one to find any American university advertisement beckoning dumb young people to attend! Rather, Universities are investing millions of dollars in information technology and exploring a myriad of ways to make their campuses, classrooms, information technologies, and teaching and learning more digitally connected and seamless all in an effort to attract smart, savvy, and high IQ students. Likewise, American universities and the higher education segment have adopted a globalization framework on which to revise and reshape general education and political science curricula. If Millennials are both citizens of a country and most importantly, citizens of planet earth, then it behooves universities to reorient curricula away from the local and toward to global.

Whether enhanced or dumb, one of the defining – if not the defining – characteristics of the Millennials is their use of new technologies in many parts of their lives, e.g., for social interaction, commerce, and for education. These new technologies, such as the Internet and satellite telephones, allow Millennials to form relationships that transcend region and even, as some have argued, the traditional barriers of race, religion, and gender. In a sense, these Millennials are the first, truly globalized generation where communication exchange transpires across the world via these new technologies.

To adjust to this new form of communication, as well as to the new globalized world in which we live, there has been a call for reform in the curriculum of the social sciences and humanities. For example, the 2006 American Political Science Association Working Group endorsed the reform to internationalize the undergraduate education of political science.[19] The reality that Millennials live in a globalized world and therefore require a better understanding of the international cultural, economic, political, and environmental challenges that confront us requires a curriculum that transcends a single national perspective. According to recent studies, less than 5% of our school teachers have any experience in international issues and less than 15% of college students have enrolled in at least four credits of internationally focused coursework.

Furthermore, in spite of international relations and comparative politics scholars who possess and teach international perspectives in their courses, U.S. faculty members across disciplines have far less training and engagement in international research, travel, and collaboration than their peers overseas. What is needed then is not only to have more international and comparative politics courses required, but also an international perspective implemented across the curriculum.[20]

It has been suggested that accomplishing this task requires the reformulation of the political science and general education curricula into a global curricula where both students and faculty develop cultural competency and empathy that enables them to see the world through the eyes of others.

As David Mason noted in the Working Group’s Report:

“[g]lobal education involves learning about those problems and issues which cut across national boundaries and about the inter-connectedness of systems – cultural, ecological, economic, political, and technological. Global education also involves learning to understand and appreciate our neighbors who have different cultural backgrounds from ours; to see the world through the eyes and minds of others; and to realize that other people of the world need and want much the same things.”[21]

For the Working Group, the state of political science is poorly equipped to provide a global education, with both undergraduate and graduate programs neither requiring international courses, nor internationalizing their curriculum. To remedy this state of affairs, the Working Group identified several best practices for the discipline of political science to adopt which include; institutional partnerships overseas; funding for international scholarly projects and faculty engagement; and lastly, a reform of the curriculum, which is examined below.

The reform of political science curricula to adopt an international perspective can occur in one of two ways: with the requirement of an international engagement and cultural competency requirement in the general education program, and/or with the requiring of an adoption of an international perspective for every course, as part of its pedagogy.[22] For example, the subfield of American politics could either adopt an internationalized perspective in its readings, assignments, and outcome objectives or it could be entirely abolished and absorbed into a comparative politics or international relations course.[23] The fact that we have a course dedicated to a single national perspective runs contrary not only to the pedagogical trends in the social sciences and humanities, but to the reality of a globalized world and generation. A recent example of this is the Globalization: Dimensions, Significance & Impact Panel at the 2008 APSA Short Course Session that called for the abolishment of the subfield of American Politics.[24] However, contrary to this pedagogical trend, a strong case can be made for having a course with a single national perspective as well as preserving the distinctive subfield of American Politics.

Political scientists have always carved out a special place for the study of particular regimes. In the first chapter of Book IV of the Politics, Aristotle categorizes the study of regimes into four types: the best regime itself, the best regime generally, the best regime for the circumstances available, and the best regime based on a presupposition.[25] These four categories correspond to the four traditional subfields in the pedagogy of American political science: political theory, international politics, comparative politics, and American politics. The study of the best regime is the purview of political theory; the study of the best regime generally is the realm of international politics; the study of the best regime for the circumstances available is the subject of comparative politics; and the best regime based on a presupposition is the field of American politics.

The fact that Aristotle lists the best regime based on a presupposition as a subject of study for political scientists reveals something important about the nature of the social sciences. Like the physician, the political scientist must have experience particular to individuals, as well as general knowledge. An adequate social science requires both a class of cases and a general theory, with neither simply reduced to the other. The reason one needs both particular cases and a general theory is that the social sciences are relatively imprecise when compared to the natural sciences. Rather than relying upon mathematical formulas, the social scientist must rely upon the proper habituation of his or her character and judgment to evaluate social and political phenomena. To learn about a regime rooted in a particular presupposition requires maturity and judgment, preferably developed through direct experience of that regime, and not merely a quantitative analysis.

American politics, therefore, cannot be studied like any other regime, because its presupposition – its ideological character, its unique culture, its peculiar historical and political development – makes it non-quantifiable and to a certain extent non-comparable. American politics falls into the class of cases rather than general theory. This is neither to deny the influence of globalization upon the American regime nor to suggest the American regime exists as an isolated wonder. Of course, the effects of globalization impact the United States, but it will be felt differently here than in other countries because of its distinctive character; and, of course, the American regime exists within a tradition stretching back to classical antiquity. Thus, how certain ideas are translated into the American experience is peculiar and particular to the regime. In essence, what is needed is a study of globalization and tradition through the lens of the American regime.

To study globalization and tradition from the perspective of the United States makes not only theoretical sense; it also serves to the proper end of education. For Aristotle, the purpose of social science is not merely to gain understanding of a regime or regimes, but to undertake an inquiry for the sake of acting and living well. If one expects one’s students to live good and noble lives – not to mention, to become good citizens – then they must learn about the particular and unique nature of their regime. Education scholars have confirmed this argument in their own work. Hunter, White, and Godbey, for example, have argued that global competence is predicated upon “a person [developing] a keen understanding of his or her own cultural norms and expectations: A person should attempt to understand his or her own cultural box before stepping into someone else’s.”[26] To learn American politics only as part of a comparative study of regimes is to deny students knowledge of how to become good citizens and good people in their own regime: for if the American regime is simply one of many, why should anyone adhere to its founding principles? Every regime has founding principles. Why should one become a good citizen when he can become a cosmopolite instead? What is the point of living in America when one can move somewhere else?

If faculty sincerely wants their students to become good citizens and virtuous people, then they must teach them about their regime as a peculiar entity, while at the same time revealing its global and traditional context. Because of the unique nature of the American regime, students can only become good citizens and good people if they understand the specifics of how their regime works. To learn American politics is to learn not only about the subject itself, but to learn how to become a good citizen and a good person within that regime. American politics must, therefore, remain a separate subfield within the discipline of political science, not only for theoretical and pedagogical reasons but also to cultivate virtue and good citizenship.

A Global Tradition: the American Political Heritage

Given the United States’ enormous and long-lasting impact on global history, the establishment of the American Political Tradition during the revolutionary era needs to be thoroughly understood by members of the millennial generation. Moreover, given the calls to internationalize the curricula of American universities, young people should fully learn that America’s founding principles and documents were debated and argued over in the eighteenth century within a dynamic global context. An examination of our nation’s beginning reveals that the Founders embraced such fundamental ideals as universal freedom and equality; and at the same time, they explicitly rejected such traits as parochialism, localism, and isolationism. Unfortunately, many of today’s Millennials mistakenly believe that globalization is a recent phenomenon – one possible only within a world of instant communication. Although the Founders certainly lacked our modern communication devices, they certainly knew, understood, and embraced the wider world beyond British America.

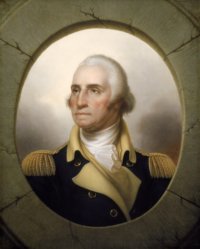

Another challenge confronting instructors seeking to place the Founding Era into a relevant and global context is that America’s revolutionary leaders simply do not look like “revolutionaries” according to the Millennials’ twenty-first century preconceptions. Lacking the ubiquitous military fatigues of a Fidel Castro or the chic beret of Che Guevara, our Founders’ silk stockings and knee-breeches give the false impression of both political conservativism and that the American Revolution itself was merely a “war for independence.” Nothing could be further from the truth.

Even a cursory look at the intellectual and political climate of the mid-eighteenth century reveals that the American Revolution took place within a thoroughly interconnected trans-Atlantic world experiencing a number of radical changes. In the years surrounding 1750, new political ideas and ideals flowed back and forth across the ocean with great regularity. The historian R. R. Palmer pointed out many years ago that revolutionary leaders and philosophers on both sides of the Atlantic essentially drew from the same “community of ideas” and, thus, Palmer famously labeled the second half of the eighteenth century “the age of democratic revolutions.”[27] Susan Dunn makes this point in her book Sister Revolutions: French Lightening, American Light.[28]

The Founders were well-aware that they lived within an interconnected global society – one marked by vibrant intellectual exchanges along with robust commercial and economic growth. A number of them had actually traveled and studied in Europe. Nine of the fifty-five delegates who attended the 1787 Constitutional Convention, for example, had studied in Great Britain at such institutions as Oxford, Edinburgh, St. Andrews, and the Middle Temple (London). Twenty-one other delegates had attended colleges within the British colonies where they learned of the European Enlightenment as well as read numerous works on history, political science, and contemporary politics written and published on the continent. In this dynamic intellectual climate, America’s revolutionaries learned to grappled with such crucial issues as the ideal structure of government, popular sovereignty, human equality, and natural rights.

Another factor which led the Founders to think globally was that most all regarded themselves as “gentlemen”, in the eighteenth century sense of the word. In the Age of Enlightenment, the term “gentleman” did not refer to one’s socioeconomic position in society or membership within a titled aristocracy. Rather, a “gentleman” of the mid-1700s belonged to a class of well-educated, well-mannered, and refined individuals whose broad-minded perspective allowed them to transcend narrow national and local boundaries. Such men regarded themselves and others like them (even from different countries) as civilized, polite, tolerant, reasonable, and morally virtuous. Lord Chesterfield best defined this “new man” of the 1700s: he was “a man of good behavior, well-bred, amiable, high-minded, who knows how to act in any society, in the company of any man.”[29] One reason George Washington would, as a youth, laboriously hand-copy The Rules of Civility and Decent Behavior, was to help him enter into this cosmopolitan class of gentlemen where status was derived by how one acted rather than by one’s family ancestry or wealth. Washington himself would later write that to be an enlightened gentleman of this age meant being, “a citizen of the great republic of humanity at large.”[30]

America’s revolutionary leaders demonstrated their transnational perspective not only through their behavior, but also in the sources they drew upon in order to articulate their own political rights, as well as to grasp the growing corruption within Great Britain’s monarchical government. Bernard Bailyn, for example, has illustrated that many educated and literate colonial Americans were very familiar with the writings of Europe’s leading secular thinkers, including Voltaire, Montesquieu, and Rousseau.[31] The English philosopher John Locke, moreover, is quoted repeatedly in pamphlet after pamphlet in the years leading up to the Revolution. Bailyn writes that the Founders also deeply read the works of the English radicals known as “the Commonwealthmen.” These writers, including John Trenchard, Thomas Gordon, and Henry St. John Viscount Bolingbroke, expressed dark fears about the growing size of the English government, its public debt, and ministerial control over Parliament through bribes and patronage. Through such publications as The Craftsman, Cato’s Letters, and The Spectator, they called upon virtuous men to become involved in public life and to work for the public good rather than their own personal ends.[32]

The key documents of the American Founding era certainly reflect these wide-ranging political and intellectual influences, especially the Declaration of Independence. A look at the origins and impact of the Declaration of Independence – the central document in the American Political Tradition – can illustrate to Millennials the Revolution’s global context. For the past century, scholars have debated the cultural and intellectual influences which guided the Founders in Philadelphia, particularly Thomas Jefferson. Just a few of the most influential works include Carl Becker, Bernard Bailyn, Garry Wills, and Pauline Maier.[33] Columbia University professor David Armitage has recently written that the Declaration “is among the most heavily interpreted and fiercely discussed documents in modern history.”[34]

Most scholars, though, agree that John Locke and his ideas in Two Treatises on Government, were probably the most influential upon Jefferson and the others Founders. The seventeenth-century English philosopher wrote this work in 1690 in the wake of the Glorious Revolution when the Dutch Stadholder, William of Orange, assumed the English throne after James II’s flight to France. Locke argued in Two Treatises that, governments were voluntarily created by self-interested citizens in order to better or more effectively protect the natural rights possessed by all human beings, especially “life, liberty, and property.” He asserted, moreover, that governments derived their legitimacy from the consent of the people. In other words, the people instituted government and the people could rebel against their government if they had sufficient cause.

Finally, Locke pointed out that all men were created equal – not in the sense that they possessed equal talent, energy and ambition – but all were invested with a core bedrock of fundamental rights that governments had to protect and which they could not abridge. Although other philosophical influences were at work, the Englishman’s natural rights philosophy is central to the Declaration’s two-paragraph introduction. It is clear, moreover, that other delegates to the Continental Congress accepted these ideas as well. For instance, though delegates made a number of changes and deletions to Jefferson’s initial draft, they did not tamper with the preamble. Ronald Hamowy argues that this was because, “American revolutionaries had long embraced the legal and political principles expounded in the natural-law theories of Hugo Grotius and Samuel Pufendorf, [which were often articulated] through Locke and the other Whig radicals, and in the continental writers inspired by them, particularly Jacques Burlamaqui.”[35] Indeed, Jefferson later acknowledged his debt to these European philosophers and their ideas. Writing to Henry Lee in 1825, he stated that that, when drafting the Declaration, he did not seek “to find out new principles, or new arguments never before thought of;” rather he looked to ideas that had emerged overseas with the intention of stating them “in terms so plain and firm as to command their assent.”

Beyond viewing the intellectual origins of the Declaration in an international context, the document itself was specifically written for a global audience in 1776. Indeed, the Continental Congress did not proclaim America’s independence to the British government nor even to the people of British America. Rather Congress announced the independence of the United States “to a candid world.” Thus they meant the document to reach the broadest audience possible and viewed it first and foremost in an international context. Given the norms of mid-eighteenth century diplomacy, American leaders realized that, “independence is ever necessary to each state,” if that state or nation is to be accorded international or diplomatic standing. Therefore, while Congress wanted to explain the principles upon which the new United States was established, its members more importantly wanted to assert why the U.S. now belonged to the larger family of nations. In fact, a global declaration of independence was essential in order to follow Emmerich de Vattel’s dictum in Laws of Nations (1758) that truly sovereign “nations [must] conform to what is required of them by natural and general society, established among all mankind.”[36]

Millennials can also better understand the global perspectives of the American Political Tradition when they examine the multiple connections between America’s founding and the French Revolution. The Founders always viewed the principles they embraced in Philadelphia (as well as in the various state constitutions and Bill of Rights) as universal. Jefferson later told the English radical cleric Joseph Priestly that, in 1776, he and his fellow revolutionaries were, “sensible that we [were] all acting for mankind.”[37] Therefore, most citizens of the United States were initially delighted in the late-1780s when French leaders seemed to embrace a revolution much like their own. The French, who had been the first to diplomatically recognize and militarily ally with the United States, had been “intoxicated” by American actions during the Revolutionary War and, beginning in 1789, looked to Americans in Paris when they first grappled with reforming their government and legal systems.[38]

More importantly, the French closely studied printed versions of America’s founding documents for guidance. Between 1778 and 1786, five different French publishers printed document-collections having to do with the American Revolution. These volumes included the Declaration of Independence, Virginia’s Declaration of the Rights of Man, as well as the various state constitutions. Between 1789 and 1791, delegates to the French National Assembly demonstrated their keen awareness of these documents (as well as of the 1787 U.S. Constitution) during their debates as they made many specific references to these pieces. Finally, the French Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen of 1789 embraced many of the same principles that Americans had taken up in their revolution: man’s natural state of equality as well as equality before the law, the abolition of feudal rights, the prohibition of a titled aristocracy, and rule by the majority. Finally, an examination of the long-term legacy of America’s political tradition is essential. As political scientists and historians understand, many later revolutionaries and global leaders modeled their new governments’ foundational principles and constitutional structures upon the actions of early American leaders. Thus a comparative examination of subsequent revolutionary movements will explain to Millennials that the American Political Tradition did not emerge within a narrow or isolated framework. Indeed, far from it.

Pedagogical Practices

To identify and understand all of these issues, Millennials must thoughtfully read and discuss a wide selection of original sources. Toward this end, we have set-up a “Teaching Module” on the Lehrman American Studies Center website designed ideally for an instructor who wishes to spend one-to-two weeks exploring this topic. When students visit this site, they read a short introduction regarding the American Revolution’s global context and are provided with links to a selection of important documents related to the Revolution and its larger impact. The documents themselves are separated into four broad categories – 1) cultural influences, 2) intellectual origins, 3) America’s founding documents, and 4) impact – so that students can more clearly see the multiple cultural, intellectual, and political influences at work both before and after 1776. The amount of reading available through this site is too extensive to all be assigned in its entirety, but an instructor can select a variety from different categories in order to expose Millennials to complex ideas, different cultures, and vastly different historical periods. Because the readings range over space and time, instructors must carefully and patiently guide their students through them. In particular, professors must carefully set the stage for their students – through substantive, yet accessible lectures and carefully-crafted discussion questions.

In order to fully grasp the intellectual roots of the Founders’ ideas, selections from Locke, the Commonwealth writers, and other figures of the European Enlightenment are available. Documents from the American founding era itself are abundant and instructors have a wide-range of pieces from which to choose; but in order to demonstrate the American Revolution’s global context, the Declaration of Independence, several of The Federalist Papers, and the Bill of Rights are vital. Furthermore, several documents from the French Revolution (especially during its initial stages) are also needed in order to place America’s founding into a broad comparative framework as well as to demonstrate how the French looked to America for its foundational governing principles when they initiated their own revolution in 1789. Finally, in order to understand the lasting impact of the American Political Tradition over the centuries, instructors can assign such pieces as Ho Chi Minh’s August 1945 declaration of Vietnamese independence, which famously opens with quotations from America’s Declaration of Independence, as well as the 1948 United Nations’ Declaration of Human Rights, which was also clearly influenced by the principles embraced in Philadelphia.

In addition to the development of an online module, podcasting is another pedagogical technique that can be used to deliver various aspects of a course. At Regent University, for example, faculty members have the opportunity to create and deliver podcasts via iTunes University. In collaboration with the university’s Center for Teaching and Learning, faculty can develop and deploy such podcasts in a relatively efficient and non-laborious manner. A case in point is the use of such podcasts for GOVT 240 American Government and Politics I – the first course in a two-course sequence of American politics in the university’s undergraduate government major. In this particular course, thirty-five podcasts were created. Twenty-five of these were video lectures and discussions, eight of these podcasts centered around eight learning units within the course with the other two podcasts serving as introductions to course assessments. Each learning unit podcast lasted from 3 to 10 minutes and provided an introduction to each unit as well as 1-2 relevant thematic questions for a student to bear in mind as she or he prepared for this learning unit. These podcasts served not only as informational tags for the students but aimed at fostering higher-level critical thinking skills within questions of American politics and its global context. Each student in the course has his or her own iTunes Regent account and subscribes to the course’s podcast. When the class met each week, students were required to have listened to each podcast with the latter serving as the introductory basis of class discussion. Each lecture and discussion was recorded and uploaded to iTunesU for students to review and further consider for preparation. This did not have any negative effect on student attendance and participation.

In spite of these new mechanism to deliver content, faculty should remember that content should always dictate the process of learning. To study transnational topics like human rights, terrorism, or citizenship, Millennials should adopt a national perspective to understand these subjects. What they will discover is that their national perspective has been shaped by other regimes and, in turn, has influenced them, too. The hope is that only a thorough and careful understanding of one’s regime first will enable Millennials to partake in the global community as thoughtful and active citizens.

Notes

[1] Strauss, Leo. “What is Liberal Education?” In Twentieth Century Political Theory, edited by S.E. Bronner (New York: Routledge, 1997).

[2] Oakeshott, Michael. The Voice of Liberal Learning (Indianapolis: Liberty Fund, 2001), 103-4.

[3] Marc Prensky, “Digital Natives, Digital Immigrants.” On the Horizon 9.5 (2001): 1-6.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Richard T. Sweeney, “Reinventing Library Buildings and Services for the Millenial Generation.” Library Administration and Management 19.4 (2005): 165.

[6] Prensky, “Digital Natives, Digital Immigrants.”

[7] Clark, Andy. “Artificial Intelligence and the Many Faces of Reason.” In The Blackwell Guide to Philosophy of Mind, by S. Stich and T. Warfield. Oxford: Blackwell, 2003), 309-21.

[8] Anders Sandberg and Nick Bostrom. “Converging Cognitive Enhancements.” Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1093.1 (2006): 201-201

[9] Jason L. Frand, “The Information-Age Mindset.” EDUCAUSE, 35 (September/October 2000): 15-24.

[10] Joshua J. Yates, “Mapping the Good World: The New Cosmopolitans and Our Changing World Picture.” The Hedgehog Review 11(Fall 2009): 7-27.

[11] Abby, Kiesa et al. Millennials Talk Politics: A Study of College Student Political Engagement. College Park: CIRCLE, 2007).

[12] Madland, David, and Ruy Teixeira. New Progressive America: The Millenial Generation. (Washington, D.C.: Center for American Progress, 2009), 15.

[13] Greenberg, Eric. Generation WE (Emeryville: Pachatusan, 2008), 13.

[14] Mark Bauerlein, “A Very Long Disengagement.” The Chronicle Review, 55 (25): B6.

[15] Bauerlein, Mark. The Dumbest Generation: How the digital age stupefies young Americans and jeoperdizes our future. New York: Tarcher/Penguin, 2008), 10.

[16] Jackson, Maggie. Distracted: The erosion of attention and the coming dark age ( New York: Prometheus Books, 2008).

[17] Siva Vaidhyanathan, “Generational Myth.” The Chronicle Review 55(Septemeber 2008): B7-B9; Thomas A. Workman, “The Real Impact of Virtual Worlds.” The Chronicle Review 55(September 2008): B12-B13; Thomas Bertonneau, “What Me Read?” William Pope Center for Higher Education Policy. (January 2009). Available at http://www.popecenter.org/issues/article.html?id=2120 (January 13, 2010).

[18] Thomas H. Benton, “On Stupidity.” The Chronicle of Higher Education. (August 2008). Available at http://chronicle.com/article/On-Stupidity/45764.

[19] Mark Cassell et al. “Internationalizing APSA,” American Political Science Association Working Group Paper (2006). Available at http://www.apsanet.org/imgtest/internationalizing%20apsa%20report4-2-06.pdf.

[20] Benjamin Barber, “Internationalizing the Undergraduate Curriculum.” PS: Political Science and Politics 40 (January 2007):105; Mary Brown Bullock, “Globalizing the Undergraduate Curriculum.” AAC& U Peer Review 1(Winter 1999): 6.

[21] Christine Ingebritsen et al. “Internationalizing APSA: A Report from the Working Group to ACE.” (April 2006). Available at http://www.apsanet.org/imgtest/Internationalizing%20APSA

%20Report4-2-06.pdf (January 13, 2010).

[22] Ibid.; also see Breton, Gilles and Michael Lambert. Universities and Globalization: Private Linkages, Public Trust (UNESCO, 1993).

[23] Basil Karp, “Teaching the Global Perspective in American National Government: A Selected Resource Guide.” PS: Political Science and Politics 25 (December 1992):703-705.; Deborah E. Ward, “Internationalizing the American Politics Curriculum.” PS: Political Science and Politics 40 (January 2007): 110-112

[24] A recent example of this is the Globalization: Dimensions, Significance & Impact Panel at the 2008 APSA Short Course Session that called for the abolishment of the subfield of American Politics. Available at http://www.apsanet.org/content_53093.cfm.

[25] Aristotle. Politics (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996).

[26] Bill Hunter, George P. White, and Galen C. Godbey, “What does it mean to be globally competent?” Journal of Studies in International Education 10 (Fall 2006): 279.

[27] Palmer, R.R. The Age of Democratic Revolutions: A Political History of Europe and America. 2 vols. (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1959-64).

[28] Dunn, Susan. Sister Revolutions: French Lightening, American Light (New York: Faber & Faber, 1999).

[29] Wood, Gordon S. The Radicalism of the American Revolution (New York: Knopf, 1992).

[30] Ibid., 22

[31] Bailyn, Bernard. The Ideological Origins of the American Revolution (Boston: Harvard University Press, 1967).

[32] Ibid.

[33] Becker, Carl. The Declaration of Independence: A Study in the History of Political Ideas (New York: Harcourt & Brace, 1922); Bailyn, Bernard. The Ideological Origins of the American Revolution (Boston: Harvard University Press, 1967); Wills, Gary. Inventing America: Jefferson’s Declaration of Independence (Garden City: Doubleday, 1978); Maier, Pauline. American Scripture: Making the Declaration of Independence (New York: Knopf, 1997).

[34] David Armitage, “The Declaration of Independence and International Law.” The William and Mary Quarterly 59 (January 2002): 40.

[35] Hamowy, Ronald. “The Declaration of Independence.” In A Companion to the American Revolution, ed. Jack P. Greene and J.R. Pole (Malden: Blackwell Publishing Ltd, 2000).

[36] Armitage, “The Declaration of Independence and International Law,” 40.

[37] Elise Marienstras and Naomi Wulf. “Translations and Reception of the Declaration of Independence.”The Journal of American History 85 (March 1999):1308.

[38] Dunn Sister Revolutions: French Lightening, American Light.

Also see “Statesmanship and Democracy in a Global and Comparative Context“

This was originally published with the same title in The Liberal Arts in America (Cedar City, UT: Southern Utah University Press, 2012).