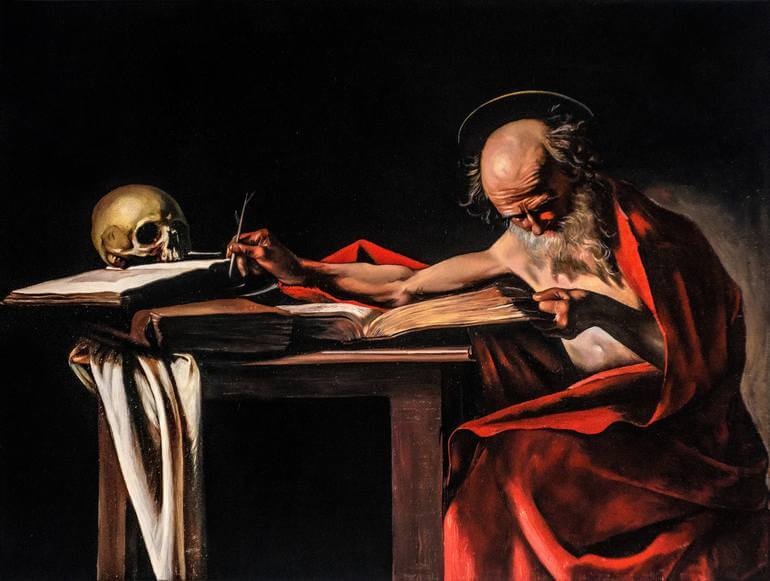

The Bible: A Memoir

I identify myself as an individual across time…. And my doing this is an expression of the deep individuality that is part of the human condition – which is the condition of a creature that can say “I.” – Roger Scruton

And God said unto Moses, I AM THAT I AM. – Exodus 3:14