The First Mystics? Some Recent Accounts of Neolithic Shamanism (Part I)

Remember that it is not you who sustain the root; the root sustains you.

-Roman 11:18

Voegelin, Mysticism, and the Stone Age

Before discussing the evidence for shamanism in the late or Upper Paleolithic period (50,000 to 10,000 years B.C.) and its significance for political science, I would like to make two preliminary points. The first concerns the meaning of Voegelin’s use of the term “mysticism” and why it can, with caution, be applied to shamanism. The second concerns the issue of why political scientists might be interested in prehistoric–or as we now say, “early historic”–periods, which include both the late Paleolithic (the focus of this paper) and the Neolithic (10,000 to 5,000 years B.C.).

Voegelin became interested in prehistory during the late 1960s, though arguably his concern with human symbolism and consciousness, which would include prehistoric consciousness, began forty years earlier. In any event, we conclude this first section with a discussion of a few of his relevant remarks prior to his encounter with Marie König in the fall of 1968. The next section deals with her arguments and why Voegelin found them attractive. In the final section we examine some of the recent discussions of Shamanism, chiefly by David Lewis-Williams and his colleagues (and criticism of their views) in the context of the late Paleolithic.

An Open-ended Approach

I might add that this paper is intended to be even more exploratory and suggestive than is usual even for the EVS. Given the existing controversies among specialists and the enormous amount of material still to be digested, in no way is it intended to be conclusive. The short but superficial answer to the implicit question of my title, “were shamans the first mystics?” is: “no.”

Quite apart from specialized arguments among anthropologists regarding the meaning of the term “shamanism,” to which we advert below, the commonsensical reason for answering this way is obvious enough: “mysticism” is a term apparently coined by Pseudo-Dionysius Areopagitica (fl. ca. 500 A.D.) to symbolize an experience of reality that transcended the noetic and pneumatic experiences and symbolizations of divine presence.

As Voegelin remarked in a letter to his friend Gregor Sebba, the term “mysticism” refers to “the awareness that the symbols concerning the gods, and the relations of gods and men, whether myth or Revelation, are secondary or derivative to the primary experience of divine presence as that of a reality beyond any world-contents and beyond adequate symbolization by an analogical language that must take its meaning from the world-content.” In this sense, he went on, Plato and Thomas were mystics: “It may horrify you: But when somebody says that I am a mystic, I am afraid that I cannot deny it” (CW, 30:751).

Whether Sebba was horrified or not, the first thing to note about the term “mysticism” and about the experience to which it refers is that they are comparatively recent, at least relative to the enormous 50,000-year span that concerns us at present. To speak of “Stone Age mysticism” is clearly anachronistic, even if we assume that shamanism existed at that time. Moreover, mysticism is (to use a Voegelinian term), a highly differentiated symbol, referring, as he said, to the inadequacy of world-immanent analogies to convey the experience of world-transcendent divine presence. Shamanic symbols, as we shall see, are by comparison highly compact.

Voegelinian Concepts

On the other hand –and leaving aside for the moment the question of evidence regarding the spiritual life of the Upper Paleolithic—that Pseudo-Dionysius was the first to give this experience a name does not mean that this particular stratum of reality had not been experienced previously even if humans had not developed the language symbols to refer to it explicitly. That is, we would argue (but not on this occasion) that the experience indicated by the term “mysticism” can also be expressed in the more compact symbolism of the shamans.

Central to that longer argument is a justification of the validity of Voegelin’s concepts of compactness and differentiation and an analysis of his discussion of the equivalences of experiences and symbolizations (cf. CW 12: 115ff). These hints will have to suffice at present as an indication that, for purposes of this paper, we accept without analysis Voegelin’s arguments and distinctions as valid. However necessary such simplifications and assumptions may be –and we must make some additional ones below– they indicate another problem. By naming an experience “mystical” we need be aware as well of a temptation, as it were, that seems endemic to naming in the first place, namely that the name will be understood as the reality.

In the high middle ages, for example, in the generation after St. Thomas, this particular problem was highlighted in the split between the dogmatic theology of nominalism associated with Ockham and the mystical theology of Eckhart. By dogma is meant the separation of symbols, usually words, from the experiences of reality to which they give articulate linguistic form. When this separation takes place, symbols can be treated as truths independent of their originary experience. The opposition of dogmatic truths sometimes expands to what Voegelin called a dogmatomachy, leading spiritually sensitive observers to recall, time and again, the derivative status of dogma. They invariably do so on the grounds of mystic experience or mystic insight into the fundamental reality experienced in sufficient profoundness to indicate the derivative and so comparatively superficial character of dogma.

Voegelin mentioned this pattern several times, often in connection with Bodin and Bergson (e.g., CW, 6: 393-8), but it may also be detected in Ficino and Pico during the Renaissance as well as in Pseudo-Dionysius in antiquity, or Hugh of St. Victor in the twelfth century (CW, 21: 47ff). The outcome, so to speak, of the rejection of dogma on the grounds of mystical experience, as with Bodin or Bergson, for example, is toleration (CW, 23:196-204; 239-40). Finally, on this point, it should be mentioned that Voegelin did not simply refuse to deny his own mystic inclinations, which in the context of the Sebba letter looks like a methodological rather than a spiritual precept, but he considered his own work to be a continuation of “classical mysticism” by means of a restoration of “the problem of the Metaxy for society and history” (Voegelin to Sandoz, 30/12/1971. HI, 27:10).

In their introduction to The History of Political Ideas , Hollweck and Sandoz distinguished between “good and bad mysticism” (CW, 19:35). 1 Apart from Bodin, Bergson and Pseudo-Dionysius, the “good mystics” included Hugh, Eckhart, Tauler, and the Anonymous of Frankfurt, each of whom the Church categorized as being a heretic (CW, 22:136; see also Voegelin’s remarks on heresy, CW 29:541-2; 33:338). Voegelin also borrowed Jaeger’s term “mystic philosophers” to refer to the generation of Parmenides and Heraclitus (CW, 15: 274 ff). Indeed, in a letter to Aaron Gurwitsch, Voegelin spoke of the “origins of philosophy in mysticism” (CW, 29:645).

The “Bad” Mystics

Among the “bad” mystics are ranged a mixed group distinguished from one another in Voegelin’s writings by the application of different adjectives. The mysticism of More and Causanus, for example, was vague and indeterminate (CW, 21: 257, 265; 22: 117, 125); Siger de Brabant was described as an “intellectual” mystic (CW, 20: 195; see also 185ff and Peter von Sivers’ note, p. 188): the Amaurians and Ortliebians were “pantheistic” mystics (CW, 22: 155-7; 180-82); Spinoza was a “cabalistic” mystic (CW, 25: 126ff); Schelling and Hegel were “epigonal” (CW, 25: 214); Nietzsche was a “defective” or an “immanentist” mystic (CW, 25: 257-61; 264-5; 296); and finally the “People of God,” Bakunin, Comte, and Marx were all “chiliastic” or “activist” mystics (CW, 22: 169-78; 188-90; 26: 294ff; 304ff).

It might be observed that Voegelin several times mentioned Rudolf Otto’s splendid study Mysticism East and West (1932).2 The modest conclusion towards which this brief survey directs us is that, for Voegelin, mysticism was a useful analytic category. So far as the other questions implied in my title are concerned, there is but one indexed reference to shamans in the Collected Works and it refers to William of Rubruck’s report of a famous debate at the court of the Mongol Khan in Karakorum at which Nestorians, Latin Christians, Buddhists and shamans disputed the superiority of their respective religions. It was a kind of precursor in everyday reality to Bodin’s literary production in the Colloquium Heptaplomeres (see CW, 20: 79-80).

New Approaches in Archeology

Turning to the second preliminary question: why are political scientists, especially those familiar with the modern political science established by Voegelin, concerned with what is conventionally referred to as prehistoric humanity? The adjective “prehistoric” is not the best. To begin with, it is a nineteenth-century French barbarism, like sociology. Even so, and ignoring its status as a linguistic mongrel, the term “prehistory” does seem to be a necessary starting point. Prehistory is distinguished from history by the existence or nonexistence of documentation and literacy. Given that literacy has been absent from some societies until quite recently, we have an obvious problem that prehistory ends at different times in different places. 3 We will simplify matters by ignoring the problem.

Political scientists usually deal with texts. The absence of texts from the Paleolithic means we must rely on the evidence unearthed (sometimes literally) by archeologists. But what is it that archeologists do that might be relevant to political science? According to one contemporary school called “postprocessural” (discussed below in section three) the goal of archeology “is to resuscitate deceased culture” by interpreting their material remains and artifacts.4 At the very least this approach seems promising because it allows contemporary human beings to say something meaningful about the extensive phenomena connected to preliterate human existence.

Of course, matters are never so simple: Historians of archeology usually distinguish between classical archeologists concerned with the material remains of Greece and Rome and archeologists interested in prehistory –in German Archäologie refers to the former only; the subject-matter of prehistoric archeology is usually referred to as Urgeschichte or Frühgeschichte. Prehistorical archeology developed from early modern antiquarianism and was initially mixed up with speculation on such matters as dating the Great Flood and the origins of specific national and ethnic groups. Thus the subject-matter relevant to political science will have to be distinguished from what is of concern to archeologists, the several “schools” of which have different approaches and priorities anyway.

Chronology and Radio Carbon Dating

One of the inevitable consequences of the Enlightenment was to separate questions of religious doctrine from those of what, to use a later term, came to be known as natural history. In France and the English-speaking world, Paleolithic archeology grew out of geology, not nationalist or ethnic antiquarianism. The speculations of Lyell and Darwin are a well known part of this story. Less well known, but equally important, is the development, particularly in Scandinavia, of principles of chronology. Specifically, Danish and Swedish nationalist antiquarians developed a “three-age theory” that postulated the succession: Stone Age, Bronze Age, and Iron Age.5

More finely calibrated chronologies soon enough were developed: the Old Stone Age was distinguished form the New; within the Paleolithic, the Lower, Middle, and Upper were distinguished from one another as well as from the Neolithic.6 Here we would note only that these eras were distinguished chiefly in terms of the predominant tool-making technologies, since stone tools are mostly what is left from these early times for archeologists to study easily.

It might also be worth noting that chronology and dating still pose significant problems, despite enormous improvements in calibration.7 Leaving aside another complex question regarding the emergence or differentiation of Homo sapiens and stability of the species, it is probably fair to say that most of the nineteenth-century accounts of the origins of stone-age humans relied either on a Darwinian model based on Malthusian liberalism or on the approach of Marx and Engels, neatly fitting new archeological evidence into the argument developed in Engels’ Origins of the Family, Private Property and the State (1884).

During the 1920s Gordon Childe advanced a kind of modified Marxist approach based on “diffusionism,” a view that Renfrew later mocked as “the diffusion of European barbarism with Oriental civilization.” 8 Renfrew could do so because of the invention of radiocarbon dating in 1947, a technique that made possible the relatively accurate dating of ancient civilizations and societies independent of any postulated Darwinian, Marxist, or diffusionist “theory.” Whatever their shortcomings, the great advantage of such theories was to provide an intelligible and relatively simple story that was, in principle, a single story of human development.

Non-linear Human Development

As an aside, I would note that, about the same time as prehistorians9 were coming to terms with the problem of the disjointedness or discontinuity of early human history, and by implication the discontinuity of all human history, Voegelin was working on a number of problems that he discussed in “Historiogenesis,” the first version of which appeared in 1960. Of particular interest in this context was his eventual rejection of a single line of historical meaning along which various events, societies, civilizations, and so on, can be strung, which was rather similar to Renfrew’s criticism of Childe (Cf. HI, 30:2). Only a brief gesture towards the problem can be made here. Those familiar with Voegelin’s argument can, one hopes, see its bearing on the present problem.

During the 1950s and 1960s archeologists and prehistorians discovered another problem: dating the appearance of Homo sapiens and charting the spread of anatomically or morphologically modern human beings across the globe. There have been plenty of revisions during the past half century: today there is a general agreement that genetic and anatomical evidence suggests the appearance of Homo sapiens in Africa between 100,000 to 200,000 years B.C. The margin of uncertainty is impressive. Evidence suggestive of what archeologists call symbolic behaviour –the use of pigment, for example—can be dated to around 164,000 years B.C. (± 12,000 years), a more modest margin of uncertainty.

The Mystery of the Mussel Shell

The interesting point for political science concerning the sites from which the evidence has been collected to make these early estimates, seaside caves in South Africa at Bolombos and Pinnacle Point, is not just that the inhabitants used red ochre for symbolic purposes, but that they ate shellfish, mostly brown mussels that South Africans still consume. Gastronomic continuity is always interesting to contemplate, but the real significance of these early mussel-eaters lies elsewhere. As the team leader, Curtis Marean, explained to his boss at the Institute of Human Origins, Don Johanson, people think shellfish are an easy food source to exploit because they don’t bite or run away.

Not so. They live underwater most of the time and even at normal low tides there is a danger of being washed off the rocks by waves. The only time brown mussels are fully exposed is during low spring tides caused (we would say) by the combined gravitational pull of the sun and the moon. From earth, such tides occur during the appearance of a full and a new moon. The significance of the mussel shells in cave 13B at Pinnacle Point dating from 164,000 years ago (± 12,000 years ) is that it is highly likely that the fisherman would have developed a tide chart based on the lunar cycle to time their visits to the shore.10

The conclusion of importance to political science is this: about the same time as the genotype Homo sapiens was more or less stabilized, which, as noted sometime between 100,000 to 200,000 years B.C.(or to use the site 13B date, around 164,000 years B.C.), this type of human began to engage in “symbolic behaviour” and began to develop a calendar. The calendar in question linked what happened in the sky, namely changes in the appearance of the moon, to changes on earth, namely the appearance of spring tides that made it relatively safe to collect brown mussels from the intertidal area. The first person to make this connection in the remote past (and obviously somebody did) had a great imagination or, to sound more scientific, he or she had a rare cognitive ability.

The Range of Unknowns

There are many other exciting problems to consider in a thorough account or these issues, including the implicit question of “more-or-less” genotype stability, before we can consider the phenomena of late Paleolithic shamanism. Consider the following questions. Given widespread agreement that the initial out-of-Africa dispersal (as it is called in homage to Isak Dinesen) took place around 160,000 years B.C., why did it take so long after that date–somewhere between 40,000 to 140,000 years–to develop the great variety of artifacts that occur in the archeological record: “bone, antler, and ivory technologies, the creation of personal ornaments and art, a greater degree of form imposed onto stone tools, a more rapid turnover in artifact types, greater degrees of hunting specialization and the colonization of arid regions” 11

Did these changes in the tempo of change as well as in extent signal a change in human cognitive capacities? And if so, what? What happened when Homo sapiens encountered Homo neanderthalis? Why, as early as 30,000 years B.C., were caves and grottoes decorated with images?12 And why only in Northwestern Europe? Does this mean that the familiar sequence noted above, from Stone to Bronze to Iron ages really applies only to this area and that elsewhere the anthropological succession from band to tribe, chiefdom, village, city, empire, etc. may prove more useful?

Many of these questions have been addressed by the relatively new subfield of cognitive archeology, and we shall consider some of their findings in the third section.

Voegelin on Early Consciousness

To conclude this section, let me remind you of a few of the opening remarks to major studies made by Voegelin that bear upon the problem of early human consciousness and political science. The first is from 1940:

“To set up a government is an essay in world creation. Out of a shapeless vastness of conflicting human desires rises a little world of order, a cosmic analogy, a cosmion, leading a precarious life under the pressure of destructive forces from within and without, and maintaining its existence by the ultimate threat and application of violence against the internal breaker of its law as well as the external aggressor.”

“The application of violence, though, is the ultimate means only of creating and preserving a political order; it is not the ultimate reason: the function proper of order is the creation of a shelter in which man may give to his life a semblance of meaning. It is for a genetic theory of political institutions, and for a philosophy of history, to trace the steps by which organized political society evolves from early ahistoric phases to the power units whose rise and decline constitute the drama of history.”

“For the present purpose we may, without further questions, accept the fact that as far back as the history of our Western world is recorded more or less continuously, back to the Assyrian and Egyptian empires, we can trace also in continuity the attempts to rationalize the shelter function of the cosmion, the little world of order, by what are commonly called political ideas. The scope and the details of these ideas vary widely, but their general structure remains the same throughout history, just as the shelter function that they are [destined] to rationalize remains the same” (CW, 19:225-6).

The second is from 1952:

“The existence of man in political society is historical existence; and a theory of politics, if it penetrates to principles, must at the same time be a theory of history” (CW, 5:88).

The third is from 1956:

“God and man, world and society form a primordial community of being. The community with its quaternarian structure is, and is not, a datum of human experience. It is a datum of experience insofar as it is known to man by virtue of his participation in the mystery of its being. It is not a datum of experience insofar as it is not given in the manner of an object of the external world but is knowable only from the perspective of participation in it” (CW, 14:39).

The last is from 1966:

“The problems of human order in society and history originate in the order of consciousness. Hence the philosophy of consciousness is the centerpiece of a philosophy of politics” (CW, 6: 33).

Symbolizing Pre-Imperial Cosmological Order

In 1940, when Voegelin wrote the first introduction of the History of Political Ideas, Western history was not usually considered to have begun with Assyria and Egypt but with Homer or even with later Greek thinkers. Voegelin was already pushing the historical horizon of political science well into the area covered by the Altertumswissenschaft of Eduard Meyer. Indeed, his reference to “early ahistoric phases” may have pushed beyond what even Meyer might have considered proper.

Notice as well that, in principle, the creation of a political cosmion from the disorder of passions and against external threats was considered a cosmic analogy that need not, in principle, be limited by any particular set of political institutions. The point of the cosmion, Voegelin stressed, was to provide a shelter within which meaning may flourish.

The opening of The New Science of Politics located philosophy of history at the centre of political philosophy, and the magisterial beginning of Order and History indicated the scope of Voegelin’s political science. Equally important, the quaternarian structure of being is known insofar as human beings participate in it. Hence the final opening sentence, from Anamnesis, which placed philosophy of consciousness at the centre of politics and history. The clarification of the structure of consciousness would also clarify the structure of being.

In his introduction to Anamnesis, David Walsh summarized Voegelin’s insight: “Philosophy of consciousness replaces the one-directionality of philosophy of history” (CW 6: 17). The question of unidirectionality was addressed in “Historiogenesis” along with its motivating centre in the anxious experience of imperial precariousness.

But what of pre-imperial cosmological order? How was it symbolized? How was its precariousness and the anxieties of consciousness aware of that precariousness expressed? Such questions, its seems to me, were brought into focus by Voegelin’s attention to philosophy of consciousness that was historical in the sense that the subject-matter to be investigated ranged from phenomena dating from remote antiquity to the present, but it was not historiogenetic in the sense that the investigation did not try to cram the archeological and paleontological evidence onto a simple time line or turn it into elements of single story. And yet, obviously the Stone Age preceded our own, which reintroduces the problems of compactness and differentiation, and of equivalences, neither of which are we able to discuss here.

One conclusion to be drawn from this section on mysticism and remote antiquity is that the application of the term to the archeological materials of the Stone Age involves a number of major problems. If they are not insuperable for a Voegelinian approach to political reality, if indeed we can say something intelligible about this evidence, considerable credit for this relatively happy outcome must be accorded to the work of Marie König.

Marie König: Contra the Mainstream

Marie König was a year older than Voegelin and had a very different personality.13 She was what the Germans call a “private scholar” (Privatgelehrtin), a mother and grandmother who apparently enjoyed doing her work surrounded by children. She often said that she did not set out to write books or pursue scholarship but was compelled to do so because of the absence of any decent studies on the caves and rock-shelters that she so much enjoyed exploring and observing.

After the war when she began her studies, German archeology, like much of German science, was still affected by the Nazi enthusiasm for “Aryanness.” The work of Gustav Kossina, particularly his two volume Ursprung und Verbreitung der Germanen (1926-7), was particularly influential and very much in step with National Socialism. Even merely nationalist and folkloric archeologists benefitted from Nazi patronage, the purpose of which was to show that the archaic Germans conformed to the Nazi image.14 One consequence was that, in the postwar milieu, German archeologists tended to keep their heads down and get on with digging, measuring, and recording. In short, they avoided “theorizing” in any way, which is to say, they simply passed on existing “theories” from the pre-Nazi period or from France.

Specifically, when König began to study the petroglyphs in the rock-shelters of the Fontainebleau forest and the images on the cave walls at Lascaux, the standard interpretative strategy was to understand the images by analogy with contemporary “primitive” peoples. Indeed, even today such hunter-gatherer peoples are often said to be “living in the Stone Age.” The assumption, called “ethnographic analogy” by archeologists, is that a San or a Navaho exists today or at the time of European contact in a way analogous to a Cro Magnon, notwithstanding the intervening 35,000 years.15

The reigning postwar theorists of “cave art,” Abbé Henri Breuil in France and Herbert Kühn in Germany, advanced their interpretations on the basis of that assumption. According to König, they also interpreted the images on the basis of untenable and a priori “theories” of primordial history (Urgeschichte) and primordial religion (Urreligion), namely that the images were evidence of magic practice designed to gain control over reality, especially hunting and fertility. As we shall see, some elements of this approach are still favoured by contemporary prehistorians.

König proceeded on the assumption that Stone Age humans were fully capable of abstract speculative thought, a position that is sometimes explicitly stated today by cognitive and postprocessural archeologists.16 The real problem was that no one understood how cave images expressed such thought. As her biographer, Gabriele Meixner, observed, “precisely the stylization and abstractions in the Paleolithic human’s pictorial world gave her cause to suspect that an ordering spirit (Geist) lay behind these creations.”17 Accordingly, König’s 1954 book, Das Weltbild des Eiszeitlichen Menschen,18 examined the Lascaux images in terms of lunar symbols rather than hunting magic. This interpretation was expanded and amplified in her larger and more interesting second book, Am Anfang der Kultur, which Voegelin helped her get published in 1973.19

The Sign Language of Early Man

The subtitle to this book, “the sign language of early man,” indicated her thesis. Very simply it was that the “art” in the French caves should be understood as religious imagery or documents. Just as a painting of a dove outside the context of a church ceases to symbolize the Holy Spirit and represents just a bird, so the paintings and images in caves lose their significance when viewed outside that context as “art.”20

Instead of considering the images as magic formulae or as expressions of totemic, primitive, or even shamanic experiences, König argued “that the development of religion began with a primordial image of the world” and that these primordial images could be detected in these early “documents.”21 That is, by looking at the cave images and rock-shelter petroglyphs in terms of the most basic orientation, one discovers in them the expression of the fundamental experiences of reality.

In Voegelin’s terminology, one would call König’s “primordial oneness” or “primordial image” the compact symbolism of “the primary experience of the cosmos,” a term Voegelin began using in the late 1960s. “We must look for explanations based on authentic material discoveries,” König wrote, “but we must do so not simply on the basis of facts in the positivist sense but rather must also take into account the world of the spirit, the supernatural, the supersensory, the realm of faith.”22

If we chose the right interpretative course, she continued, we will be led to the intellectual categories (Denkkategorien) of the high civilizations, the rich spiritual life of which is familiar to us through writings and other documents. Once the notion of the superlatively stupid (urdumm) primitive is abandoned along with the outmoded evolutionary theory that supported it, we need to consider the best way of understanding the spiritual world of early humanity. This approach must be based on the “documents” as she said–Voegelin would likely have referred to the “materials”–namely the evidence found in the tools and images created by early human beings.

König’s example, tool-making, illustrated her point. Tools may be thought of as “materialized ideas” and were typical, not idiosyncratic or random. Hence there was an order or a tradition and even a beauty to them. But the first act–of creating an axe from a stone, for example–was entirely creative, an initiative. Once patterned it could be reproduced and inspire other inventions–needles, for example. “Every cultural object,” König said, “concretized a thought,”23 which means that the thought was primary or determinative of the result. Accordingly, the “tool” was initially multi-purpose before being specialized into knife, scraper, axe, etc. Likewise–and here she followed Arnold Gehlen–with the spiritual development of humanity: in the beginning was a relatively undifferentiated experience and symbolization of the whole.

The Genesis of Homo Spiritualis

König provided a commonsensical analysis of the genesis of Homo spiritualis as well as what occasionally amounted to a speculative philosophical anthropology. For example, the experiences of hunger and cold quickly inform anyone of the physical basis of existence. Hunting and control of fire answer that experience with food and warmth–and it is perhaps worth stressing that for large stretches of human prehistory, the inhabitants of, say, South or East Africa, were refugees from extensive glaciation and desertification. In such refugia as existed, food and warmth would be high priorities.

But the eyes of early humanity exceeded the ability to do something directly on the world around us (Umwelt): the stars and the sky brought human beings new ideas, but of a different kind, and this, too, needed explanation. Thus the mysterious rhythms of the heavens were seen as being connected to the mysteries of birth, life, and death, as well as practical matters such as estimating the times of low tides to collect brown mussels. At the same time as hunger was sated and early human beings achieved what Hegel called “sentiment-of-self,” a glance at heaven, as Aristotle said, initiated a new experience for which nothing is to be done except think.

No tool, no material embodiment of thought is possible. What is possible is a different mode of cognition that required the imagination or what König called “faith” and Voegelin called “participation.” And at the same time, this mode of cognition was directed at the mystery of birth, life, and death, which are obviously connected to the material issues of eating and keeping warm, but are not exhausted by them. That is, if you don’t eat or keep warm, you die. But even if you do eat and keep warm, you still die. Thus the first mode of consciousness, Hegel’s Selbstgefühl, cannot account for, or be reduced to, the second, Aristotle’s wonder.

Wonder is autonomous even while it is dependent upon a body that needs to be fed and kept warm. In addition to the stars and the sky and their rhythms, there were other forces that could not be seen but nevertheless were there–the wind and the seasons, for example–and still others–volcanoes–that, even though they could not be controlled like hunting and keeping warm, could be observed but not measured or anticipated. To put it another way, part of the primordial image of the world was that it was dangerous, precarious, as Voegelin said in The History of Political Ideas. Humans were at its mercy and so felt dependent, but they could reflect on their dependency and so felt connected to the world and grateful for their connection.

Existence may be precarious, but not chaotic; there is order and human existence unfolds within a cosmion. This complex of experiences required special behaviour–a cult and a ritual space could make these invisible realities visible and so accessible. The primordial forces, more fundamental even than the material necessities of food and warmth, were accordingly symbolized, not to control them, as contemporary prehistorians almost universally assume, so much as to connect early humans with an invisible reality. In Voegelin’s language, participation in reality, not control of phenomena, was the motivation for this basic experience and symbolization, what he called the primary experience of the cosmos.

Symbolic Relics

“The oldest objects to have been found that were not tools and that therefore raised the question of their cultic purpose,” Archaeologist Marie König wrote, “were spheroids.” The oldest of these, she said, dated from the end of the Lower Paleolithic, some 300,000 years B.C. If this dating is accurate, it belongs to the very earliest possible time, according to the fossil record, of human habitation, shortly after the separation of Homo erectus and Homo sapiens.

In any event, these spheroids were three or four inches in diameter and so could be held in the palm of the hand. That they were spheroids was of great significance to König. The spheroid, she said, “was the ideal shape (Gestalt) for the as yet undifferentiated fundamental concept (Grundbegriff) because alone it is the perfectly uniform figure” (Figur). In addition, the visible cosmos, especially as made evident in the nocturnal motion of the planets and stars, made the sky look like a vault. So, König argued, the cosmos could be represented in this primordial way either from the outside, as a sphere, or from the inside, as a vault with the observer at the centre. The skull, being both spheriod and hollow was highly suitable as a representation of both perspectives. This may be why so many skulls and skull fragments have been preserved. In any event, for one reason or another, skulls have long been treated in a special way.

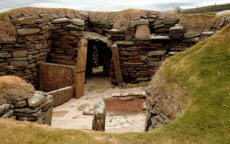

The undifferentiated cosmos/sphere/vault was, she argued, the primordial and unstructured representation from which developed a more differentiated structure of an above and a below (or nether world), often understood to be lying in water–a spring, for example, could also be an entrance to the netherworld. Likewise a cave is a liminal space that, moreover, can serve as a terrestrial representation of the cosmos as a whole. From the Middle Paleolithic, 150,000 to 50,000 years B.C., or Mousterian (named after a French rock-shelter), spheroids were in continuous use and skulls were treated with care.

Mousterian burial remains, including those of Neanderthals, arranged along an east-west axis, presuppose close observation of the stars and especially of the sun. Such observation of the world axis gave additional structure to the cosmos. This axis, however, cannot be represented by a sphere or a vault, but only by a straight line. Nor can it be derived from a sphere or vault. Even more remarkable, a north-south axis, which also appeared in the Mousterian period, cannot be derived from observation of the rising and setting of the stars but is, so to speak, an act of pure speculation.

By the Middle Paleolithic, therefore, humans used their imagination to develop a cosmic focal point where the two axes intersect. At the same time, humans created the four cardinal directions. Again, this articulation of the cosmos was likely known to Neanderthals who also laid their dead in square burial pits.

Refining Representations of the Cosmos

Without going into detail concerning the lines and scratches, the “cup-marks” and “nets,” some surrounded by circles, some not, to be found in the rock-shelters and caves in the Fontainebleau forest (some of which were visited by Voegelin in the company of König),26 we may simply note that, according to König, the process of distinguishing cultural achievement from natural formations began some 300,000 years ago, possibly prior to the appearance of anatomically modern humans. Whatever the date assigned to these artifacts, it seem plausible enough that the primordial and universal symbolization of reality was the sphere.

Increased specificity or “differentiation” to use Voegelin’s term, provided a more precise structure of upper and lower, symbolized, for example, as two bowls or cups or even two parts of a clam shell. Then the observation of the bowl of the sky could be structured in terms of lines and points, which in turn created a means of communication that enabled further differentiation of the structure of the cosmos as a grid or a net. Sometimes natural weathering of rock produced such an effect; sometimes it can be observed on sacred animals such as the turtle. From spheroids, to crossed lines, to grids, representation of the order of the cosmos grew more elaborate in its internal articulation. “The crossed lines,” König wrote, “are part of the commandments of order (Ordnungsgeboten). Its axes make up the imaginary lines of connection between the cardinal points.”27

The point at which the lines crossed was seen as the centre of human existence and the square cultural world put boundaries or limits on space. The fifth cardinal point could divide the cosmos into four squares or four triangles if the lines were drawn diagonally. Sometimes the boundary rectangle was not incised and only the four corners of a diagonal or rectangular cross is today visible in the rock. If the centre of the world can be symbolized by an intersection of two lines, a third dimension can also be symbolized by a vertical line, thus connecting the sky and the netherworld. Again, these petroglyphs can be bounded or not. In all such ideograms the focus was at the centre where all the axes intersect, rather like the crosses on the Union Jack.

The Order of Time

König followed the discussion of spatial order in and of the cosmos with a discussion of the order of time, starting with circadian and lunar rhythms. Here the central symbol was not the four cardinal points but the three phases of the moon, which could be symbolized as three lines, a triangle, three cup-marks, dots, and so on.

König argued that the pictorial representation of the “horned moon” (A Midsummer Night’s Dream, V:1, 245) could be found in the horns of aurochs painted on the walls at Lascaux, for example, but that the later representation, however appealing to modern aesthetic sensibilities, was supplementary. In other words, since both the horns and dots or lines of three represented the phases of the moon, they can be understood as expressing an equivalent meaning.28

König provided a great deal of evidence from Fontainebleau, Lascaux, and later agricultural societies to support her account of the Paleolithic origins of cosmological symbolizations of space and time. She argued that the symbolization of time by way of the moon and then by representational images was subsequently used to symbolize death and rebirth, for example. Of course, the details can grow complex rather quickly.

Granted that the moon was a heavenly clock and that it could be compared with earthly phenomena, which ones? And if these earthily phenomena then could change from one thing–a pair of auroch’s horns–to another: a triangle, three dots, etc., then “any number of symbolic images that bore no external relationship to one another” might yet be responses to the same experience.29 This was especially true with the new moon and its constituting an “answer” to the anxieties of life and death.

The König Argument

Complexities aside, König’s chief point was that, if we examine the “documents” in caves and rock shelters with this perspective in mind, it becomes clear that the earliest humans had a more differentiated culture than they at first appear to do, especially if we think of human prehistory as a development towards historical and eventually modern and contemporary humanity.

To summarize König’s admittedly speculative argument: the spiritual comprehension of the cosmos began with the creation of a spheroid cosmic image. Subsequently it was differentiated into space and time, which nevertheless remained constituents of the whole. A new problem arose as a consequence of differentiation: how to relate the spatial and temporal “dimensions” of the cosmos to one another in an intelligible representation of reality that is both a primordial unity and a differentiated reality?

Some late Paleolithic examples would be: (the order of space = 4) + (the order of time = 3) = 7. Or: a grid of 3×3=9 lines, cup-marks, dots etc. make a square (nine is also the number of nights for each phase of the moon) that serves as a comprehensive ordering image of the cosmos. One further observation: Marie König has all but been ignored by the “professional” archeological community. One obvious reason for this, as will be clear in the next section is that for the most part archeologists have in recent years pursued an entirely different interpretative strategy, one more congenial to the materialist and indeed often self-declared atheist assumptions of contemporary evolutionary scholarship.30

Such approaches are highly critical of “speculations” such as those carried out by König but are utterly immune to the irony that their own work is deeply informed by speculative assumptions that never rise into their own consciousness of what they are doing or thinking. About the only exceptions I have been able to discover during the past couple of years of research on this problem are archeologists interested in Paleolithic and Neolithic calendars, such as Alexander Marschack, who was also considered “controversial.”31 König was fully aware of her marginal position. As she told Meixner, “I don’t dig and date; I interpret.”32 There is also, no doubt, a certain disdain for a “layperson” intruding into the clerical orders of esteemed archeologists at the heads of important institutes, not to forget the importance of old-fashioned sexism.

König and Voegelin: Helping Each Other

Voegelin himself may have entertained some highly traditional notions regarding the sexual division of labour, especially as it applied to academic life, but he did not allow his prejudices to get in the way of his ability to appreciate genuine insights by female scholars. Upon hearing her lecture at the Academic Institute of Rome during the fall of 1968, according to König, Voegelin “came up to me straight away and said: ‘we must work together.’”33

They did, in fact, meet several times at her home in Saarbrucken and, as noted above, she escorted him around the caves and rock shelters at Fontainebleau, and, no doubt partly in return for her help, Voegelin assisted her with the publication of Am Anfang der Kultur. Voegelin even deputed two of his students, Tilo Schabert and Klaus Vondung, to assist her in writing some of the material in the first chapter dealing with archeological methods and assumptions. In short, it was a two-way street. As Schabert said to Meixner: “Frau König was also important to him. He wasn’t interested in her for no reason.”34

In a letter to her dated 14 October, 1968, Voegelin explained her importance to him:

“Your essay [on prehistoric symbolism] is of great value to me because it shows that an historical picture can indeed be crystallized out of the most diverse specialized prehistorical archeological sciences that goes back at least to the beginnings of Homo sapiens.”

“You can understand the importance such an account has for me from the fact that the prehistoric symbols are the same as those that are found in the earliest written texts on political symbolism, i.e., in the Egyptian texts of the 3rd millennium B.C”.35

“Through comparison of these Egyptian texts with the symbolism as you have presented it, the decisive step becomes possible in separating the remnants of tradition from those symbols specific to an imperial civilization. Up to now I have used the term “cosmological” for the Egyptian and Mesopotamian civilization. This term can still be used, but it is impossible to separate the cosmological from the imperial elements.”

“Many thanks, too, for the reference to the Handbuch der Vorgeschichte by Hermann Müller-Karpe. I immediately ordered it for the Institute. I am happy to say that I can already use the insights that I have gained from you in this semester in my lectures on the philosophy of history” (CW 39: 576-7).

In this letter Voegelin was not simply being a courtly Viennese gentleman. He was expressing his genuine gratitude to a fellow scientist. In September, 1970 he wrote Hans Sedlmayr, the respected art historian and his colleague at Munich:

“In my Order and History I dealt with the symbols of the ancient Oriental societies in the manner in which they are depicted in the sources. However, this method has proved to be inadequate, since most of these symbols have a prehistory reaching back into the Neolithic, if not into the late Paleolithic. The symbols that appear in the ancient Oriental empires are adaptations of older symbols to the new imperial situation. I am now trying to research pre-imperial symbols as far as they can be followed back into prehistory” (CW 30: 664).

Later that year he wrote Manfred Hennignsen about König’s “fantastic collection of photographs” of cave and rock-shelter images and inscriptions. “Once again . . . we see evidence of the presence of the primary experience of the cosmos and its symbolization at least [back] into the Neolithic age, and perhaps even into the Paleolithic” (CW 30: 675).

Despite having also acquired an impressive collection of photographs himself, Voegelin did not manage to integrate this new material into his later publications. In the course of his lectures, however, he would occasionally mention the cave images and petroglyphs in an offhand way that his audiences found somewhat disconcerting, indeed baffling, a response that he both anticipated and clearly enjoyed.36 One conclusion seems obvious: like Eric Voegelin, Marie König looked for a constancy of equivalent meanings in the experience and symbolization of reality starting with the earliest possible evidence.

Notes

1. See also R.C. Zaehner, Our Savage God, (London, Collins, 1974) which makes a similar argument in favour of this distinction.

2. See, for example, CW, 33:333 and his amusing remarks on Meher Baba, Voegelin to Ernst, 7/01/1974 in CW, 30: 780.

3. See Colin Renfrew, Prehistory: The Making of the Human Mind (London, Phoenix, 2008), vii.

4. James L. Pearson, Shamanism and the Ancient World: A Cognitive Approach to Archeology, (Lanham, Altamira Press, 2002), 76.

5. Bruce G. Trigger, A History of Archeological Thought, 2nd ed., (Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2009), 104-5, 121-38.

6. Michael Chazan, “Concepts of Time and the Development of Paleolithic Chronology,” American Anthropologist, 97 (1995), 457-67.

7. Anne Solomon, “What is an Explanation? Belief and Cosmology in the Interpretations of Southern San Rock Art in South Africa,” in Henri-Paul Francfort and Roberte N. Hamayou, eds., in collaboration with Paul G. Bahn, The Concept of Shamanism: Uses and Abuses, (Budapest, Akadémiai Kiado, 2001), 169.

8. Renfrew, Prehistory, 41.

9. The term often used today to refer to anyone, whether formally trained as an archeologist, an anthropologist, a paleontologist etc. who is concerned with prehistoric human beings.

10. See Donald C. Johanson and Kate Wong, Lucy’s Legacy: The quest for Human Origins, (New York, Harmony, 2009), 263-5. The original study by Marean et al. is “Early Human Use of Marine Resources and Pigment in South Africa during the Middle Pleistocene,” Science, vol. 449 (18 October, 2007), 905-09.

11. Steven Mithen, “From Domain –Specific to Generalized Intelligence: A Cognitive Interpretation of the Middle/Upper Paleolithic, in Colin Renfrew and Ezra B.W. Zubrow, eds., The Ancient Mind: Elements of a Cognitive Archeology, (Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1994), 32.

12. Some prehistorians and archeologists connect the extinction of the Neanderthals to the symbolic capability of the newly arrived Homo sapiens. The argument, very simply, is that Homo sapiens could create symbolically sustained and so larger social networks than the face-to-face contacts to which the Neanderthals were allegedly restricted. See Clive Gamble, The Paleolithic Societies of Europe, (Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1999), 382. See also Matt J. Rossano, “Did Meditating make us Human?”Cambridge Archeological Journal, 17:1 (2007) 47-58. On the other hand, Gregory Cochran and Henry Harpending, The 10,000 Year Explosion: How Civilization Accelerated Human Evolution, (New York, Basic Books, 2009) 36, 53, argue that interbreeding between the two species of Homo both extinguished the Neanderthals and accelerated the development of symbolic interaction among modern humans. As Leo Strauss once said of a similar issue, God knows who is right.

13. Some of the material in this section was initially analyzed by Jodi Bruhn. We are planning to write a more extensive and thorough account that will examine in considerably greater detail than can be done on this occasion the questions introduced in a preliminary way here.

14. See H. Hassmann, “Archeology in the ‘Third Reich,’” in Heinrich Härke, ed., Archeology, Ideology and Society: The German Experience, (Frankfurt, Peter Lang, 2000), 65-139; see also Härke, “’The Hun is a Methodical Chap,’” in Peter J. Ucko, ed., Theory in Archeology: A World Perspective, (London, Routledge, 1995), 46-60. See also: Bettina Arnold, “The Past as Propaganda: Totalitarian Archeology in Nazi Germany,” Antiquity, 64 (1990), 464-78; Suzanne L. Marchand, Down from Olympus: Archeology and Philhellenism in Germany, 1750-1970, (Princeton, Princeton University Press, 1996), ch. 9-10; Martijn Eickhoff, “German Archeology and National Socialism: Some Historiographical Remarks,” Archeological Dialogues, 12:1 (2005), 73-90.15. For an analysis of the problems of ethnographic analogy consider the observations of R. Lee Lyman and Michael J. O’Brien, “The Direct Historical Approach, Analogical Reasoning and Theory in Americanist Archeology,” Journal of Archeological Method and Theory, 8 (2001), 303-42.16. Philip G. Chase and Harold L. Dibble, “Middle Paleolithic Symbolism: A Review of Current Evidence and Interpretations,” Journal of Anthropological Archeology, 6 (1987), 263-96; Robert G. Bednarik, “Paleoart and Archeological Myths,” Cambridge Archeological Journal, 2:1 (1992), 27-43.17. Meixner, Auf der Suche nach dem Anfang der Kultur: Marie E.P. König, eine Biographie, (Munich, Frauenoffensiv, 1999), 77.18. Marburg: Verlag N.G.Elwert, 1954.19. König, Am Anfang der Kultur: Die Zeichensprache des frühen Menschen, (Berlin, Gebr. Mann Verlag, 1973). See also CW, 30: 641.20. “The category … ‘rock art’, has no validity to those who created what we study . . . . We are dealing with a class of things defined by ourselves: ‘rock art’ exists only within Western civilization.” Anthony Forge, “Handstencils: Rock Art or Not Art,” in Paul Bahn and Andrée Rosenfeld, eds., Rock Art and Prehistory: Papers Presented to Symposium G of the AURA Congress, Darwin, 1988, (Oxford, Oxbow Monograph, 10, 1991), 39

21. Am Anfang, 22.

22. Am Anfang, 25-6.

23. Am Anfang, 30.

26. I was able to examine several sites in May 2008 and in May 2010 thanks to the support from the Earhart Foundation and to Joe Donner and the Donner Canadian Foundation. The 2010 visit was assisted by the expert guidance of M. Alain Bernard of the Groupe d’Etudes, de Recherches et de Sauveguard de l’Art Rupestre and of M. Guy Blanchard, a local inhabitant with an interest in caves and other rock formations; to them both I am very grateful.

27. Am Anfang, 102.

28. One might make the same argument regarding North American “rock art,” with the racks of bighorn sheep, which are often “exaggerated” serving in the place of European aurochs. See David S. Whitley, Cave Paintings and the Human Spirit: The Origins of Creativity and Belief, (Amherst, Prometheus Books, 2009), 93-4; 145.

The notion that the horns on the Lascaux bulls are images of the moon and so of the order of time is supported by the argument of Eduard Hahn, that aurochs were first domesticated not for beef but for “religious purposes” such as sacrifice. Animals were selected and selectively bred, he argues, because the “gigantic curved horns resembled the lunar crescent.” Hahn’s Die Hausteire und ihre Beziehungen zur Wirtschaft des Menschen, (1896) is summarized in Eric Isaac, “On the Domestication of Cattle,” Science, 137 (1962) 195-204.

29. Am Anfang, 238.

30. Mary Lecron Foster, “Symbolic Origins and Transitions in the Paleolithic,” in Paul Mellars, ed., The Emergence of Modern Humans: An Archeological Perspective, (Ithaca, Cornell University Press, 1990), 517-39.

31. See his The Roots of Civilization: The Cognitive Beginnings of Man’s First Art, Symbol and Notation, (New York, McGraw Hill, 1972).

32. Meixner, Auf der Suche, 95.

33. Auf der Suche, 139.

34. Auf der Suche, 141.

35. The English translation substituted “third century” for third millennium (des 3. Jahrtausends) HI, 21:151

36. I witnessed one such performance in Montreal in 1970. I had little idea what he was talking about, but neither, so far as I could tell, did anyone else. See CW 33: 275-6.

This is the first of two parts with part two available here; also available is “Narrative, Neanderthals and Art: An Analysis of Upper Paleolithic Differentiation,” “Human Emergence as Cosmic Metaxy,” “How to Think About Human Origins,” and “From Big Bang to Big Mystery.”