The First Mystics? Some Recent Accounts of Neolithic Shamanism (Part II)

Dismissive Views of Shamanism

A generation ago anthropologists often dismissed shamanism as “a made-up, modern, Western category, an artful reification of disparate practices, snatches of folklore and overarching folklorizations, residues of long-established myths intermingled with the politics of academic departments, curricula, conferences, journal juries and articles, and funding agencies.”37 The reason for this severe judgment seems to have been a close association of the term with doctrines of cultural evolution that most anthropologists no longer considered appropriate.

On the other hand, a few years later, the study of shamanism underwent a renaissance as a result of a new interest in the study of altered states of consciousness, an interest in shamanism as therapy, as well as in assorted New Age experiments in spirituality. The last-named sources of the recent revival in shamanistic practices are important for the current understanding of contemporary society in the industrial west in the same way that Zen or Hare Krishna were significant modifications of Buddhist and Hindu religious practices in the middle decades of the last century.

The great appeal of this latest alternative to traditional religious and institutionalized Western religions is that, with or without the assistance of chemicals, it achieves quickly results that are deemed by practitioners to be satisfactory. Students of traditional shamanism are by and large skeptical of “urban shamans” on the grounds that the phenomenon says more about contemporary city-dwellers than it does about shamanism.38 In any event, our concern is not with this “veritable cottage industry.”39

A variation on the theme of shamanism as a New Age spiritual alternative is the notion that it is therapy. Just as Carlos Castaneda (Don Juan) is said to provide a chemical short-cut to realizing human spiritual potential, so too does the argument that shamans are really psychotherapists provide an intelligible and rational account of shamanic practice–as well as taunting conventional Western psychotherapy much as New Age religiosity taunts traditional Western religions.40

In the more scholarly world of cultural and social anthropology, general theories of shamanism have given way to detailed and particular studies of specific practices in equally specificcultural context.41 Here the focus is on small-scale societies and their internal politics, on the impact of colonialism or gender, language, or ritual. The focus of these studies, however fascinating in other respects, is to underline the observation that shamanisms are always embedded in specific but encompassing cultural practices and ways of living. Since our chief concern is with Paleolithic symbolism, most of this material can also be ignored

Shamanism and the Behavioral Psychologists

Such general theorizing as exists currently deals with consideration of the psychological state of the shaman. The concern is not on what is different among shamanic practices but on recurring likenesses that are to be explained by an analysis of the mental health of shamans. From early in the twentieth century one assumption has been that shamans were mentally unbalanced,42 or as we say nowadays, they suffered from “mood disorders.”43 Often on the basis of the same evidence, compelling or at least persuasive arguments have been advanced that shamans were and are entirely sane.44

Current disputes seem to center on the proposition that, however unusual shamanic experience may be, it is within the behavioral repertoire of normal, that is, sane humans.45 It would seem that shamanic consciousness is a matter of degree of alteredness. The key to the current understanding of shamanism as an altered state of consciousness among both anthropologists and archeologists was apparently the widespread experimentation with drugs during the 1960s. Anthropologists studying the use of psychedelic drugs particularly among South American shamans saw some obvious parallels (perhaps) with their own youthful experiences.46

By and large these very modern behavioral scientists were skeptical regarding the experiences of spirit worlds and sought to explain these altered states of consciousness by way of brain physiology and brain chemistry.47 Unlike the anthropological prehistorians who have been unable to study Paleolithic and Neolithic shamans, the adherents of the approach that considers shamanism as an altered state of consciousness can proceed as if the same physiology as today was at work 30 thousand years ago.

We will consider this assumption below. For the present it is enough to observe that it is not universally accepted as valid. Kehoe, for example, simply rejected the notion of “survivals of primordial or Paleolithic, religion among non-Western nations” as being “contrary to evolutionary biology.” As a consequence, “we have no present means of determining states of consciousness of prehistoric humans.”48

Whether evolutionary biology is as reductionist as the arguments of those who advocate altered state of consciousness as a function of brain chemistry, we need not try to determine. It does seem to be true, as Atkinson said, that reductionism of any kind “has been off-putting to sociocultural anthropologists.” Indeed, she likened this approach to “analyzing marriage solely as a function of reproductive biology.”49

The Phenomenological Approach and Mircea Eliade

An alternative to the highly focused and particularist approach to the study of shamanism as undertaken by social and cultural anthropologists is the hermeneutical and phenomenological approach used by scholars of comparative religion, notably Mircea Eliade.50 “Shamanism in the strict sense,” Eliade wrote, “is preeminently a religious phenomenon of Siberia and Central Asia.”51 He provided linguistic and etymological reasons for accepting this “strict” understanding of the practice but added that a preliminary definition that shamanism is a “technique of ecstasy,” meant that there were many additional locales of shamanistic practice besides Siberia.

Indeed, according to Eliade, “it would be more correct to class shamanism among the mysticisms than with what is commonly called a religion.”52 Likewise he wrote in the preface to his book that shamanism is “at once mysticism, magic, and ‘religion’ in the broadest sense of the term,” which is precisely what Eric Voegelin meant by a compact symbolism.53 By starting with the most obvious and widespread instances of shamanism, Eliade was able to criticize a number of reductionist arguments. Early studies of Arctic Siberian shamans attributed their neurophysical condition to the cold, to long winter nights and attendant sensory deprivation, lack of vitamins and so on.

So far as Eliade was concerned, however, from within the horizon of Homo religiosis all such “explanations” along with varieties of insanity are simply irrelevant:

“The mentally ill patient proves to be an unsuccessful mystic or, better, the caricature of a mystic.His experience is without religious content, even if it appears to resemble a religious experience, just as an act of autoeroticism arrives at the same physiological result as a sexual act properly speaking (seminal emission), yet at the same time it is but a caricature of the latter.”

Likewise the use of intoxicants, from hashish to vodka, has been widely reported. “But what does this prove concerning the original shamanic experience? Narcotics are only a vulgar substitute for ‘pure’ trance,” and moreover a recent one that points to “a decadence in shamanic technique.” Such “narcotic intoxication” provides “an imitation of a state that the shaman is no longer capable of attaining otherwise.” Decadence and imitation, the substitution of the “easy way” for the “difficult way” appears in many forms across the world where shamanism is practiced.54

Eliade’s conclusion was straightforward: Arctic shamanism “does not necessarily arise from the nervous instability of peoples living too near the Pole and from epidemics peculiar to the north above a certain latitude.” Nor, more broadly, is a shaman a sick person; “he is, above all, a sick man who has been cured, who has succeeded in curing himself.”55

Levi-Strauss and the Kwakiutl Shaman, Quesalid

The great strength of phenomenology is that it–literally–gives an account (logos) of an appearance (phenomenon) and thus aims to avoid all reductionist fallacies. For their part, anthropologists and archeologists concerned more with the rich variety of existing dissimilarities rather than with common or essential meanings, have ignored or dismissed phenomenology as “German idealism” of no use in serious field work.56

Eliade, however, was not engaged in field work–for which he has naturally been criticized by archeologists and anthropologists.57 Because he was interested in the essence or meaning of shamanism, he offered as his initial description of shamanism a “technique of ecstasy” or “trance,” or even “possession.”58 That is surely what it appears to be. But what, then, is ecstasy, trance, or possession?

Roberte N. Hamayon, for instance, asked “are ‘Trance’, ‘Ecstasy,’ and similar Concepts Appropriate to the Study of Shamanism?”59 And she answered: “no.” Trance may be a useful and intelligible concept for Western analysts, she said, but shamans describe their experience as being in direct contact with spirits. Do they? Really? To answer such questions, consider the story told by Lévi-Strauss about a Kwakiutl shaman, Quesalid.60 It seems that Quesalid did not believe in the power of shamans but he was curious about the tricks they used and decided to expose them.

He started hanging out with shamans until one asked him to join the group. He learned how to dissimulate, how to vomit, and how to eavesdrop, all considered essential shamanic skills. He was especially adept at extracting a concealed tuft of down from his mouth after throwing it up covered with blood that came from biting his own tongue. This “bloody worm” would be presented to the patient as being a pathological body he had just sucked out of the sick one, through the skin, for example, but without breaking it.

Soon Quesalid had all the evidence he needed for an exposé on a Bernstein and Woodward scale. But then a sick person asked him to cure his sickness, the patient having dreamed that Quesalid was just the man for the job. He cured the patient and became known as a powerful shaman. Quesalid explained that what happened was that his patient simply believed in him. But then he visited a neighbouring group of Koskimo Indians where, instead of using the trick of the fake bloody worm pathogen, the local shaman simply spat on his hands.

Quesalid was skeptical still, especially when the Koskimo spitting technique didn’t work a cure. So he asked permission to try to cure the Koskimo patient using his own Kwakiutl bloody worm (i.e., concealed tuft of down and tongue-biting) technique. He did so and his patient proclaimed herself cured. (Hallelujah!) Quesalid had further adventures, sometimes with unpleasant consequences for fakers other than himself, and Lévi-Strauss drew the only sensible conclusion: “Quesalid did not become a great shaman because he cured his patients; he cured his patients because he had become a great shaman.”61

Huizinga, St. Francis of Assisi, and Conscious Play

In case this example and the commentary on the position of Quesalid are taken as nothing but an expression of the French love of paradox, consider the remarks of Jan Huizinga regarding St. Francis of Assisi:

“St. Francis of Assisi revered Poverty, his bride, with holy fervor and pious ecstasy. But if we ask in sober earnest whether St. Francis actually believed in a spiritual and celestial being whose name was Poverty, who really was the idea of poverty, we begin to waver. Put in cold blood like that the question is too blunt; we are forcing the emotional content of the idea.”

“St. Francis’ attitude was one of belief and unbelief mixed. The Church hardly authorized him in an explicit belief of that sort. His conception of Poverty must have vacillated between poetic imagination and dogmatic conviction, although gravitating towards the latter. The most succinct way of putting his state of mind would be to say that St. Francis was playing with the figure of poverty.”62

Huizinga went on to point out that Francis’ entire life was filled with play-factors and play-figures, “and these are not the least attractive part of him.” Readers of Huizinga’s book will recall that play, even in puppies, is not merely physiological: it is significant; it means something.63 One need not explicate Huizinga’s account of play to acknowledge that one of its essential aspects is that the player is aware that he or she is playing.

Ecstasy and Sky, Earth and Underworld

There is no reason to think that Quesalid was unaware of the game he was playing, which meant that playing the trickster was not simply to be a fake.64 The two great roles shamans play are those of healer, such as Quesalid, and psychopomp, a guide or companion to recently deceased souls in the afterlife. The shaman can play these roles, Eliade said, because, in his ecstatic experience, he can “abandon his body and roam at vast distances, can penetrate the underworld and rise to the sky.”65 Indeed, his ability to pass from one cosmic region to another, from earth to heaven or to the underworld is “the pre-eminent shamanic technique.”

“This communication among cosmic zones is made possible by the very structure of the universe . . . .the universe in general is conceived as having three levels–sky, earth, underworld–connected by a central axis. The symbolism employed to express the interconnection and intercommunication among the three cosmic zones is quite complex, . . . [but] the essential schema is always to be seen, even after the numerous influences to which it has been subjected; there are three great cosmic regions, which can be successively traversed because they are linked together by a central axis.”

This axis, of course, passes through an “opening,” a “hole;” it is through this hole that the gods descend to earth and the deal to the subterranean regions; it is through the same hole that the soul of the shaman in ecstasy can fly up or down in the course of his celestial or infernal journeys.66

Those familiar with Voegelin’s concept of metaxy can think of shamans as human beings whose lives are lived emphatically in the metaxy, in permanent movement along the axis mundi, a concrete image of the Voegelinian philosophical concept of “tension.”

The Shaman as Intracosmic Traveler

Those familiar with Voegelin’s concept of Metaxy can think of shamans as human beings whose lives are lived emphatically in the Metaxy, in permanent movement along the axis mundi, a concrete image of the Voegelinian philosophical concept of “tension.” The mystic shamanic communication among the three realms is expressed in architectural structures such as ziggurats, but also in trees and bridges or the smoke-hole (and smoke) of a tipi or yurt. Indeed the notion of a cosmic centre or omphalos, which Marie König found in the patterns and lines and cup-marks in the Fontainebleau rock-shelters, does not end with shamanism and the mystic cosmic flights of shamans but reappears as a millennial constant whatever the degree of compactness and differentiation of experience and symbolization.67

The ability of the shaman to use the axis mundi as a flight-path can easily transform the shaman into a one-person omphalos. For the many, the center of the world, the Delphic omphalos, for example, is a site that permits them to send offerings, prayers, or messages to the gods, whereas for the shamans it is the starting point for flight. “Only for the latter is real communication among the three cosmic zones a possibility.”68 Thus what for the rest of the community remains a cosmological ideogram is for the shaman a mystical itinerary. For members of the audience of a shamanic séance, his or her presence would very much seem to be the real presence of a cosmic omphalos.

The three cosmic zones are zones of a whole, which is why, as Åke Hultkrantz observed, shamanic ecstasy or trance is not a mystical union with a cosmic-transcendent divinity that one finds in “the ecstatic experiences of the ‘higher’ forms of religious mysticism.”69 Rather, shamanic ecstasy is intra-cosmic. By traversing the structure of the cosmos, namely its three zones, the shaman reaffirms the unity of the cosmos, what Voegelin called the primary experience of the cosmos. Strictly speaking (and reflecting the problem of equivalences of experience and symbolization) as indicated in section one, shamans cannot be mystics, notwithstanding Eliade’s assertions to the contrary.

The Evolving Theories of Archeology

The first interpretation of the images at Lascaux to discuss their shamanic elements was published in 1952.70 Since then such interpretations, along with criticism and counter-criticism, have become a minor archeological industry. From its origins in the seventeenth century, archeology has been based on modern assumptions and presuppositions. As is true of other social sciences, during the twentieth century archeology has been strongly influenced (or corroded) by positivism.

In recent decades, as Trigger pointed out, “archeological theorists have looked to philosophy to provide guidance in matters relating to epistemology or theories of knowledge.”71 Two approaches widely used today, called the functional and the processural, have tried to move beyond the “naïve positivism” of an earlier generation. The functionalists try to understand past social and cultural “systems” from the inside by focusing on the routine; processuralists try to do the same thing, but by focusing on discontinuities and irreversible changes. There are also even newer approaches espoused by postprocessuralists, who seek to “use material culture to investigate past human behavior and human history”72 and “cognitive archeologists.”73

The Usefulness of Cognitive Archeology

According to Colin Renfrew, cognitive archeology is “the study of past ways of thought as inferred from natural remains.”74 There are, obviously, numerous challenges to gaining such an ambitious goal, but it does not seem to be, in principle, unattainable. James N. Hill, for example, said: “Although I continue to maintain that we cannot actually know what prehistoric people thought, I now think that it is sometimes possible to make plausible inferences about what they must almost certainly have thought, given very strong circumstantial and analogical evidence.”75

“Perhaps,” said Renfrew, “the most concise approach [to indicate the scope of cognitive archeology] is to focus explicitly upon the socially human ability to construct and use symbols.”76 The purpose of such an archeological approach, he added, is not, however, so much to determine the meaning of symbols as to see how they are used, which looks like a prudent first step.

Likewise, Richard Bradley observed that a cognitive archeology looks at, say, petroglyphs as “deposits of information” rather than trying to determine what they mean.77 There is even a “phenomenological archeology.”78 These more recent schools or approaches, but to different degrees, have also abandoned old fashioned positivism.

The Difficulties in Comparing Shamanism to Cave Art

Because two cognitive archeologists, David Lewis-Williams and Jean Clottes, along with David Whitley in the US, have addressed the question of shamanism in connection with Paleolithic cave images and rock-art, we will consider some of their findings in detail. As did Marie König before them, both Lewis-Williams and Clottes rejected the opinion that the images were simply decoration,79 or totemism,80 or, of course, an aid in practicing sympathetic magic to ensure fertility or a successful hunt.

As they pointed out, “the subjectivity of these observations is obvious” and so, too, is its arbitrariness.81 Lewis-Williams was trained as an anthropologist and did his field work among the San of his native South Africa. He was especially interested in San rock art and its formal similarities to Paleolithic materials. At the same time, he was aware of the limitations (or fallacies) of “ethnographic analogy”–in this case, the application of San shamanic experience and understanding and its relationship to their rock art as a means of explaining or interpreting Paleolithic cave images.

Some processural archeologists have pointed out an obvious general problem of comparing cave art to shamanism:

“What must be explained is . . . the artist’s conviction that the art must be created fearsomely deep within the dark, slippery, clammy earth. It’s not the same as a Siberian shaman drumming, dancing and then divining in a tent or cabin filled with the people of the community. Darkness inside a dwelling doesn’t equal darkness through a mile of twisting rock.”82

To this general objection there is added the issue of comparing the sunny open air and rock shelter venues of San rock art with the subterranean location of Paleolithic images.83

A Constant Physiology Suggests a Constant Human Capacity

Starting in the 1980s, Lewis-Williams argued that a non-arbitrary but universally valid model that by-passed the problem of “diffusion” or continuity can be found in the structure of the human brain. Such a model could apply equally to San and Cro-Magnon human beings. Because, as he and Clottes put it, the humans living in the Upper Paleolithic “had the same nervous system as all people today,” or at least “we may confidently assume” they did, “we have a better access to the religious experiences of Upper Paleolithic people than to many other aspects of their lives.”84

Over the years Lewis-Williams’ confidence has grown: what began as assumptions became facts. In 2005, for example, “the neurological functioning of the brain, like the structure and functioning of other parts of the body is a human universal.”85 By 2010, “modern research on the ways in which the human brain functions to produce the complex experiences we call consciousness provides a foundation for an understanding of religion that unites its social, psychological and aetiological elements.”86 Various “mental states,” he said, are both physiological and neurological and “as integral to the human body as, say, the digestive system.” Indeed, these “mental states” are simply “the product of the human brain.”87

Lewis-Williams also argued, on the basis of brain physiology, in favour of what he called a “spectrum” of human consciousness, consciousness being “a notion or sensation, created by electro-chemical activity in the ‘wiring’ of the brain.”88 This “spectrum” extended from “alert consciousness” to altered state of consciousness hallucination. “Alert consciousness is the condition in which people are fully aware of their surroundings and are able to react rationally to those surroundings.” It is not, however, easily definable because people tend towards “inward” states as well, which Lewis-Williams calls “reflective.” Beyond reflection on this “spectrum,” lies daydreaming, dreaming and deep trances. “In these states people believe that they are perceiving things that are, in fact, not really there; in other words, they hallucinate.”89

Some Obvious Problems with the Lewis-Williams Theory

There is a rough-and-ready or commonsensical meaning to what Lewis-Williams (and Clottes) argued, but no one would begin to claim it was a philosophically sophisticated account of human consciousness. Nor does it accord with all the anthropological and archeological evidence. Indeed, Alison Wylie raised the obvious Popperian objection: “what would count as disconfirmation of the model?”90 Likewise Bahn argued that there was no evidence for a “multi-stage” spectrum nor any reason to connect cave imagery to hallucination, neither as recollected in lucidity and certainly not as a condition for painting the images.91 Nor is there a universal connection between rock-art and trance.92

Such empirical objections aside, one can agree that there is a distinction to be made between alertness and being in a trance, but consider the assumption (apart from the notion that such a “spectrum” is in the first place, real): perception is lucid because it is of real things in the world; the mark of reality of such things is that they can be dealt with “rationally.” Everything else, from reflection–or thinking–to hallucination is progressively irrational and unreal.

Readers of Voegelin, to say nothing of other philosophical anthropologists, will have learned that not all consciousness is perceptual and not all experiences of non-perceptual realities are irrational.93 Accordingly, a more adequate philosophical anthropology is needed in order to distinguish perceptual and usually practical and alert consciousness of the world, and equally alert and rational analyses or explorations of the ground of the world and human participation in the search for its meaning.

Science Understood as “a Matter of Method”

Lewis-Williams and his colleagues are unaware of this problem apparently because they share a fairly common misunderstanding, namely that “science” is a matter of method.94 Since this assumption is held by their critics as well, the collective discussions remain inconclusive and not very meaningful because they do not, properly speaking, penetrate to an analysis of the relevant principles.

In any event, the corollary drawn by Lewis-Williams is that, “although there are many diverse cultures in the world, there is today only one kind of science.” Indeed, “for the material world in which we live, there is only science.” Accordingly, “we must look to the material world for evidence that there is a spirit realm.” As a consequence, only “religion” can impinge upon “science” since there is, for science, nothing strictly speaking to impinge upon with respect to religion–save fantasy and other altered states of consciousness. The final conclusion is entirely predictable: “Science does not attempt to answer questions about the meaning of life . . . . In fact, the questions are meaningless.”95

This assertion by Lewis-Williams is not quite as vulgar and unscientific (in Voegelin’s sense) as it sounds. Let us agree, for purposes of extracting what we can from an interesting but philosophically and methodologically weak account, that “science”–in this case, neuroscience–deals only with method. Content, what fills up consciousness, whether alert or altered states of consciousness, is provided by “culture” much as food fills up the digestive system with which Lewis-Williams compared the neurobiology of the brain. And “culture,” it seems, is as variable as food. On these grounds, Lewis-Williams and his colleagues claim they are not “determinists.”

“Just as other parts of human bodies are the same as they were during the Neolithic, so too is the general structure of the human brain and its electro-chemical functioning. Lest this statement seem simplistic and deterministic, we make explicit a key caveat. We distinguish between the fundamental functioning of the nervous system and the cultural milieu that supply much of its specific content.”96

Apart from remarks declaring the meaningless of questions such as “What is the meaning of life?” or the notion that “religion” is simply a question of an altered state of consciousness and thus of fantasy, there are additional internal reasons to indicate the limitation to this argument about scientific “form” and cultural “content.”

The Dangerous Bridge

Apart from remarks regarding the meaninglessness of questions regarding the meaning of life or the notion that “religion” is simply a question of “altered states of consciousness” and thus of fantasy, there are additional internal reasons to indicate the limitation to this argument about scientific “form” and cultural “content.”

First, we recall from Mircea Eliade’s discussion of shamanism his mentioning of the “perilous passage” to the underworld and his provision of several examples from shamanistic practice. He noted that the symbolism is linked, on the one hand, with the myth of a bridge (or tree, vine, etc.) that once connected earth and heaven and by means of which human beings effortlessly communicated with the gods. On the other hand, it is related to the initiatory symbolism of the “strait gate” or of a “paradoxical passage.”97 Eliade elaborated this symbolism in light of a “myth of origins,” which is one way of discussing the meaning of life.

By crossing, in ecstasy, the “dangerous” bridge that connects the two worlds and that only the dead can attempt, the shaman proves that he is spirit, is no longer a human being, and at the same time attempts to restore the “communicability” that existed in illo tempore between this world and heaven. For what the shaman can do today in ecstasy could, at the dawn of time, be done by all human beings in concreto; they went up to heaven and came down again without recourse to trance.

Temporarily and for a limited number of persons–the shamans–ecstasy reestablishes the primordial condition of all mankind. In this respect, the mystical experience of the “primitives” is a return to origins, a reversion to the mystical age of the lost paradise. For the shaman in ecstasy, the bridge or the tree, the vine, the cord, and so on–which in illo tempore connected earth with heaven–once again, for the space of an instant, becomes a present reality.98

The Vortex and the Shaman Cave

For Lewis-Williams, however, the rich symbolism of the passage with ladders and trees and so on is reduced to the single image of a “vortex.” The vortex is what “draws” the shaman into the underworld and so into the depth of the trance. The vortex experience may be accompanied by sensations of darkness, constriction, difficulty in breathing and so on. Entry into a cave is a physical enactment of the vortex experience. It may be accompanied by “social isolation, sensory deprivation, and cold” that assist the shaman in entering into a trance.99

Why a vortex instead of a bridge, a ladder or even a beanstalk?

Because the experience of a vortex is one of the stations that appear on the notional “spectrum” of consciousness between lucidity and hallucination.100 Moreover, understanding the vortex experience as neurologically induced allows for a seamless discussion of shamanism in terms of hallucinogenic chemicals.101 At one point Whitley compared the shamanic vortex to having “drunk too much, laid [sic] down in bed, and felt the room spin around.”102 Even William James did not go so far as this. A similar argument disposed of the incisions, grids and dots that were central to Marie König’s interpretation of space and time–surely products of the most lucid of mental events.

For Lewis-Williams, they were simply “entopic,” like seeing stars when you press your palms into your eye-sockets with your eyes closed.103 These entopics, besides stars, included grids, spirals, dots and of course the vortex.Of the remaining forms, the “claviform,” is shaped like a paddle and the “techtiform” is shaped like a chevron. Because, apparently, there were no corresponding entopic images, they became “the most mysterious figures in cave art.”104

In sum, for the neurophysically inclined prehistorians, Eliade’s distinction between shamanic spirituality and its degenerate counterfeit is nonexistent. When the focus is on brain chemistry, despite the gesture in the direction of culturally variable content, it could hardly be otherwise. In other words, if a decontextualized ecstasy or altered state of consciousness alone, rather than its purpose or goal, is all that is of concern to an investigator, then the account of the experience is incomplete. Again Bahn made the obvious comment: entopics “merely establish the not-terribly-illuminating fact that the [Paleolithic] artists had the same nervous system as ourselves,”105 which, of course, is where we began.106

Saving the Cave Phenomena

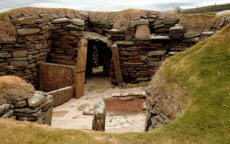

There is not much to be gained in belaboring the methodologically induced limitations of neurophysical accounts of Neolithic or Upper Paleolithic shamanism. What is of interest to political science is that these accounts also contain some useful and helpful descriptions that can be reinterpreted phenomenologically. To begin with, the physical structure of some of the caves, Lascaux, for example, or Chauvet, suggests that large halls near the entrance, like the nave of a medieval cathedral, were suitable for community purposes. The acoustic properties of these spaces made them attractive for playing flutes and drums as well.

In contrast, further inside, sometimes after having to negotiate (literally) a difficult or narrow passage, there were smaller side-chapels (to continue the medieval image) or sanctuaries where only a few or sometimes only a single person could penetrate at one time. Since many of these halls, sanctuaries, or shrines are located hundreds of meters from the fresh air and sunlight, penetrating the darkness with the kinds of illumination available to Paleolithic humans was not lightly undertaken and certainly not by the claustrophobic and faint of heart.107

A second obvious observation, endorsed by Eliade as well, is that caves mediate the everyday world and the underworld. This means that the making of images in a subterranean locale must have been the extension of a pre-existing cosmology. That is, one would not venture into a deep cave for no purpose, no more than one would go to the effort of scratching the sides, roof, or floor of a rock-shelter simply to leave doodles or Stone-Age graffiti. In short, the artists experienced “a suite of subterranean spirit animals and beings before they started to make images of them in caves.”108

Despite our present proclivity to admire the accuracy of selected aspects of the animals represented, the images are not naturalistic: there is no grass or trees, no mountains, rivers or ponds, not even the sun and the stars; there are no humans and no representations of human artifacts such as fire, huts, tools, weapons–and no dogs or even wolves.109 This does not mean that such external phenomena are not present in an abstract fashion, but it does strongly suggest that the animals were spirit-animals, not everyday ones.

The Importance of Image Location

A third obvious characteristic of cave or “parietal” art is that it does not move. Hence the importance of the use of walls, choice of panels, placement of figures and local topography. It matters not just what was painted but where.110 The question of where the images of aurochs and bison or deer and horses were placed led to considerable discussion when, following a decade of research, in 1968 André LeRoi-Gourhan, building on the previous work of Annette Laming-Emperaire, published The Art of Prehistoric Man in Western Europe.111

LeRoi-Gourhan argued on the basis of the structuralism developed by Lévi-Strauss in favour of the existence of a complex structure among the images. The groupings, he said, constituted a mythogram of considerable complexity. The basic elements were male and female or rather, maleness and femaleness. The cave itself was the expression of a meaning. Paleolithic people represented in the caves the two great categories of living creatures, the corresponding male and female symbols, and the symbols of death on which the hunters fed. In the central area of the cave, the system is expressed by groups of male symbols placed around the main female figures, whereas in the other parts of the sanctuary we find exclusively male representations, the complements, it seems, to the underground cavity itself.112 In short, LeRoi-Gourhan argued that the placement of the images expressed Paleolithic ideas of the supernatural organization of the natural world.

The achievement should in no way be minimized even if it has largely been abandoned by prehistorians. The reason, which is commonly directed against structuralist interpretation by critics, as Lewis-Williams put it, is that the interpretation “was built on friable empirical foundations. The mythogram was too good, too neat, to be true.”113Maybe so, but Lewis-Williams agreed that LeRoi-Gourhan and Laming-Emperaire were likely correct “in their beliefs that the caves are indeed patterned.”114 The great problem is to establish, first, what the patterns are and, despite the tentative injunctions of the cognitive archeologists, to answer the more important question: what do they mean?

In the continued absence of a persuasive general account however, Lewis-Williams and his colleagues were content to observe that, contrary to the presupposition of a structuralist interpretation of the presence of an a priori structure or schema in the mind of the artist prior to painting the images, the artists often made used of the already given contours of the walls. That is, they adapted their painting to the three-dimensional walls of the cave in order, one might plausibly argue, to enhance their significance.115

The Rock Wall as Veil to the Spirit World

Two other aspects of Lewis-Williams’ discussion of cave walls are significant. The first, which he initially discovered in connection with San rock-art,116 is that the rock face should be considered a veil or membrane on the other side of which lay the spirit world, the true cosmic underground. This interpretation reinforced the connection between the cave as a physical space that is literally under ground and the cave as a cosmic liminal space that provides access to the lowest tier of the cosmos.117 The context of the images, as noted above, was inherently meaningful. It was not just an out-of-the-way place to draw things or doodle.

A second insight built on the appearances of the rock face as a membrane: the paint of the images “dissolved” the membrane to allow the otherwise invisible spirits on the other side to slip through and appear. That is, “the images were not so much painted onto rock walls as released from, or coaxed through, the living membrane . . . that existed between the image maker and the spirit world.”118 Such a description, I submit, is phenomenologically astute. Moreover, because it requires the active and imaginative participation of the conscious, even meditative spectator, it is essentially compatible with Voegelin’s philosophy of consciousness.

Finally, Lewis-Williams noted, the use of cracks, nodules, ledges, hollows, and bulges, which were often incorporated into the images, had the effect of giving them more of a 3-D appearance. And given the poor light thrown by Paleolithic lamps, one can easily imaging a chiaroscuro effect: move the light one way, the image disappears; move it another and it emerges through the membrane from the cosmic underworld.

And yet, there is a big difference between a cave wall and a wall in the open air simply in terms of accessibility. Moreover, if the images are indicative of a membrane, what are we to make of antlers, or bone and other so-called mobilary (i.e., portable) art, that carried the same images?119 In other words, Lewis-Williams’ notion of a membrane at the cave wall, while highly suggestive, is quite incomplete.

However that may be, the appearance of the walls as membranes on the other side of which lay the spirit world made sense of the otherwise enigmatic hand prints that decorate many of the walls. These were made either by pressing the paint-laden hand onto the wall (called a positive print) so that the paint mediated the human hand and the membrane, or they were negative, which is to say, stencils, likely made by blowing or spitting paint onto the wall and hand so that an outline of the hand appeared–or, if you prefer, the hand disappeared behind a layer of paint propelled by breath, sealing it into the rock membrane.120 These lines of interpretation or reinterpretation add additional dimensions to the meaning-focused interpretation of Marie König and so suggest a spiritual experience of considerable complexity.

Prehistorical Social Organization

Before drawing a few summary conclusions, I would note that Lewis-Williams and his colleagues made a number of other observations in passing that suggest additional avenues of research. For example, large caves with extensive decorations likely served as cult centres that, in turn, would likely have had a political side to them. Obviously the actual painting of the images, hundreds of meters from the cave entrance and far higher on the wall than an individual can reach from the floor, required considerable organization–for provisioning of artists, scaffold construction, lighting, and so on.

They also noted that the degree of social organization and political power required to build Neolithic structures such as Newgrange was orders of magnitude greater.121 This problem of what might be called pragmatic prehistoric politics, so far as I know, has hardly been examined, let alone connected to shamanism or equivalent spiritual practices.122 In this connection one would wish to explore the connections among cave images, rock-art and paleoastronomy, which clearly was of importance during the Neolithic period.123

Why Did They Do It?

What conclusions can be drawn from this rather extensive but far from complete discussion of archeological literature that might be useful for political science?

Let us start from the most obvious: having concluded that the philosophical limitations of the archeologists whose remarks in the area of philosophical anthropology or of philosophy of consciousness are poorly argued and appear more like personal idiosyncrasies than serious methodological flaws, let us ask the following question:

“Why did Paleological humans crawl into long, dirty, pitch black, muddy, dangerous, cold caves with poor lighting that might easily be extinguished to guide them on their way in order to draw aurochs or hand prints, grids, dots and spirals?”

Shamanism and associated communal rituals provide an intelligible answer. The cave painters actualized the tiered cosmos by placing their images on the membrane that separated and thus connected materiality and spirituality.

With respect to shamanism, because shamanic experiences are associated with hunting rather than agriculture, as Hultkrantz said, “there is therefore good reason to expect that shamanism once was represented among Paleolithic hunters.” At the same time, “it is impossible to say whether shamanism belongs to the very old ingredients of the once universal hunting and gathering cultures.”124

Zaehner’s response to mescalin can be generalized in the sense that there may be no single meaning to trance or hallucination, which varies across cultures.125 Likewise, as Bahn pointed out, the problem is not that the Paleolithic symbolisms have no meaning but “that they have many, doubtless extremely complex meanings” so that simple and reductionist explanations are the first thing to be avoided.

After all, who is so bold as to claim to know the meaning of the Mona Lisa or even of the Wreck of the Medusa?126 In short, the search for universal explanations of parietal art may be a wild goose chase–or to put it in a more scholarly way, it is perhaps premature to look for universal explanations or universal meanings–at least if we reject the claims by Lewis-Williams and his colleagues regarding altered states of consciousness (and we do).127

We are not however simply raising another cry for “more research.” In terms of Voegelin’s “search for volume zero,”128 the discovery of an ordered cosmos expressed in Paleolithic symbolism verified his remark to König that the cosmological aspects of the symbolism of the Ancient Near East can, in fact, be distinguished from the imperial ones.

At the end of 500 pages of analysis and presentation of evidence, Eliade came to the same conclusion: “there is no solution of continuity in the history of mysticism.”129 To use Voegelin’s language, a phenomenology of mystic experiences brings to light equivalences of experience and symbolization, not a continuous time-line of mystic ideas. Of course, we may expect to find a guide to pre-literate mystic symbolizations in later narratives, but our presupposition is not one of historical continuity. Accordingly, so far as the present paper is concerned, whether one describes the Paleolithic religion as shamanism or not, and whether one described shamans as mystics or not, seems to me to be a secondary issue.130

Notes

37. M. Taussig, Shamanism, Colonialism, and the Wild Man: A Study in Terror and Healing, (Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 1987), 146.

38. See, for example, G. Flaherty, “The Performance Artist as the Shaman for Higher Civilization,” Modern Language Notes, 103:3 (1988), 519-39; M. Harner, The Way of the Shaman, (New York, Bantam, 1982).

39. R. Walsh, “What is a Shaman? Definition, Origin, and Distribution,” Journal of Transpersonal Psychology, 21:1 (1989), 1. See also Danièle Vazeilles, “Shamanism and New Age: Lakota Sioux Connections,” in Francfort et al., eds., The Concept of Shamanism, 367-87.

40. See E. F. Torry, The Mind Game: Witch-Doctors and Psychiatrists, (New York, Bantam, 1972).

41. See Andrzej Rozwadowski, “Sun Gods of Shamans? Interpreting the ‘solar-headed’ petroglyphs of Central Asia,” in R. N. Price, ed., The Archeology of Shamanism, (London, Routledge, 2001), 65-86; Charles Lindblom, “Shaman, Shamanism,” entry in T. Barfield, ed., The Dictionary of Anthropology (Oxford, Blackwell, 1997), 424-5.

42. See G. Devereux, “Shamans as Neurotics,” American Anthropologist, 63 (1961). 1088-90; J. Silverman, “Shamanism and acute Schizophrenia,” Ibid., 69 (1967), 21-31 and literature cited.

43. David S. Whitley, Cave Paintings and the Human Spirit, 210ff, 257.

44. R. Noll, “Shamanism and Schizophrenia: A State-Specific Approach to the ‘Schizophrenia Metaphor’ of Shamanic States,” American Ethnology, 10 (1983), 443-59.

45. Jane Monnig Atkinson, “Shamanisms Today,” Annual Review of Anthropology, 21 (1992), 309.

46. The connection between mystic visions and intoxicants has along and respectable lineage. William James, for example, remarked “The sway of alcohol over mankind is unquestionably due to its power to stimulate the mystical faculties of human nature . . . . It brings its votary from the chill periphery of things to the radiant core. It makes him for the moment one with truth.” Varieties of Religious Experience, (London, Longmans Green, 1902), 397. On the other hand, as Zaehner more soberly remarked: “To the average frequenter of cocktail parties this may come as a revelation. That there is a grain of truth in it may be conceded, but to state that by drinking three or four gin and tonics the drinker becomes ‘one with truth’ would surprise no one more than the drinker himself.” R.C. Zaehner, Drugs, Mysticism and Make-Believe, (London, Collins, 1972), 48.

47. Marlene Dobkin de Rios, Hallucinogens: Cross-Cultural Perspectives, (Albuquerque, University of New Mexico Press, 1984).

48. Alice B. Kehoe, “Eliade and Hultkrantz: The European Primitivist Tradition,” in Andre Znamenski, ed., Shamanism: Critical concepts in Sociology, vol. III, (London, Routledge Curzon, 2004), 262, 268.

49. Atkinson, “Shamanisms Today,” 311.

50. Shamanism: Archaic Techniques of Ecstasy, tr. Willard R. Trask, Bollingen Series, LXXVI (New York, Pantheon, 1964). Anna-Leena Siikala, “The Interpretation of Siberian and Central Asian Shamanism,” in Znamenski, ed., Shamnism, 173, said Eliade’s approach “has remained unknown among the anthropologists.” It is probably fair to say that archeologists have simply ignored or dismissed Eliade’s arguments and the assumptions from which they were developed. See Alice Beck Kehoe, Shamans and Religion: An Anthropological Exploration in Critical Thinking, (Prospect Heights, Waveland,Press, 2000); Guilford Dudley III, Religion on Trial: Mircea Eliade and his Critics, (Philadelphia, Temple University Press, 1977); Brian Rennie, Reconstructing Eliade: Making Sense of Religion, (Albany, SUNY Press, 1996); John A. Saliba, “Homo religiosis” in Mircea Eliade, (Leiden, Brill, 1976).

51. Shamanism, 4.

52. Shamanism, 8.

53. Shamanism, xix.

54. Shamanism, 24, 401. We will consider the issue of the “difficult way” below. The fraudulence of the “easy way” was confirmed by the Oxford scholar of comparative religion, R.C. Zaehner, many years ago in connection with Aldous Huxley’s famous experiments with mescalin. See Zaehner, Mysticism Sacred and Profane: An Inquiry into some Varieties of Praeternatural Experience, (Oxford, Oxford University Press, 1957). Mescalin, he reported, mostly made him laugh and giggle.

55. Shamanism, 27. See also Joan Halifax, Shamanism: The Wounded Healer, (New York, Crossroad, 1982).

56. See Bruce G. Trigger, A History of Archeological Thought, 474.

57. Kehoe, “Eliade and Hultkrantz,” 269.

58. A. Hultkrantz, “Ecological and Phenomenological Aspects of Shamanism,” in V. Dioszegi and M. Hoppal, eds., Shamainsm in Siberia, (Budapest, Akadémiai Kiado, 1978), 43.

59. In Znamenski, ed., Shamanism, 243-60.

60. In Claude Lévi-Strauss, “The Sorcerer and his Magic,” in Structural Anthropology, (New York, Basic Books, 1963), I, 175-85. The original report was provided by Franz Boas in 1930.

61. “The Sorcerer and his Magic,” 180.

62. Huizinga, Homo Ludens: A Study of the Play-Element in Culture, (Boston, Beacon Press, 1955), 139.

63. Huizinga, Homo Ludens, 1.

64. Of course, not all archeologists would agree. For Paul G. Bahn, “the shaman is actually a showman.” See his “Save the Last Trance for Me: An Assessment of the Misuse of Shamanism in Rock-Art Studies,” in The Concept of Shamanism: Uses and Abuses, 55 and references.

65. Shamanism, 182. To which A. Hultkrantz added the roles of diviner, magician, and priest. See his “Ecological and Phenomenological Aspects of Shamanism, 27-58.

66. Shamanism, 259.

67. I have discussed this question in connection with the relatively differentiated symbolism of Plato in “’A Lump bred up in Darknesse,’ Two Tellurian themes in the Republic,” in Zdravko Planinc, ed., Politics, Philosophy, Writing: Plato’s Art of Caring for Souls, (Columbia, University of Missouri Press, 2001), 80-121. The inhabitants of Toronto, where we met in 2009, routinely refer to their city as the centre of the universe. They look upon the axis mundi of the CN Tower as proof–as if proof, in such self-evident matters, were needed!

68. Shamanism, 265. See also E.A.S. Butterworth, The Tree at the Navel of the Earth, (Berlin, de Gruyter, 1970), 172 ff.

69. Hultkrantz, “Ecological and Phenomenological Aspects of Shamanism,” 41-2.

70. Horst Kirchner, “Ein archäologicher Beitrag zur Urgeschichte des Shamanisimus,”Anthropos, 47 (1952), 244-86.

71. Trigger, A History of Archeological Thought, 303.

72. Trigger, A History, 505. See also Harald Johnsen and Bjørnar Olsen, “Hermeneutics and Archeology: On the Philosophy of Contextual Archeology,” American Antiquity, 57 (1992), 419-36.

73. See Renfrew, Prehistory, 107ff.

74. Renfrew, “Towards a Cognitive Archeology” in Renfrew and Zubrow, eds., The Ancient Mind, 3.

75. Hill, “Prehistoric Cognition and the Science of Archeology,” in Renfrew and Zubrow, eds., The Ancient Mind, 83.

76. Renfrew, “Towards a Cognitive Archeology,” 5.

77. Bradley, “Symbols and Signposts: Understanding the Prehistoric Petroglyphs of the British Isles,” in Renfrew and Zubrow, eds., The Ancient Mind, 100.

78. Joanna Brück, “Experiencing the Past? The Development of a Phenomenological Archeology in British Prehistory,” Archeological Dialogues, 12 (1), (2005), 45-72.

79. This view is still occasionally advanced. See J. Halverson, “Art for Art’s Sake in the Paleolithic,” Current Anthropology, 28:1 (1987), 63-89.

80. Henri Delporte, L’Images des Animaux dans l’Art Préhistorique, (Paris, Picard, 1990).

81. Jean Clottes and David Lewis-Williams, The Shamans of Prehistory: Trance and Magic in the Painted Caves, tr., Sophie Hawkes, (New York, Harry N. Abrams, 1998), 71.

82. Kehoe, Shamans and Religion, 78.

83. In any event, it is not self evident that the Central Asian or North America shamanic practices are related to the San experiences. According to Francfort, for instance, “from a basic methodological point of view, it is odd to compare the art of the San, which is narrative and anecdotic, with the European cave art, which is naturalistic and descriptive. The founding principles of these two art are essentially different.” Specifically the San art depicts alleged shamanic actions and ceremonies; the Paleolithic allegedly depicts beings obtained from shamanic visions. Henri-Paul Francfort, “Art, Archeology, and the Prehistory of Shamanism in Inner Asia,” in Francfort, et al., eds., The Concept of Shamanism, 248.

84. Clottes and Lewis-Williams, The Shamans of Prehistory, 12-13.

85. Lewis-Williams and David Pearce, Inside the Neolithic Mind: Consciousness, Cosmos, and the Realm of the Gods, (London, Thames and Hudson, 2005), 6. See also 40, 62.

86. Lewis-Williams, Conceiving God: The Cognitive Origin and Evolution of Religion, (London, Thames and Hudson, 2010), 137.

87. Lewis-Williams, Conceiving God, 158. See also 161, 209-10.

88. Lewis Williams, The Mind in the Cave: Consciousness and the Origin of Art, (London, Thames and Hudson, 2002), 104.

89. Clottes and Lewis-Williams, The Shamans of Prehistory, 13-4.

90. Wylie, “Comments” to J.D. Lewis-Williams and T. A. Dowson, “The Signs of all Times: Entropic Phenomena in the Upper Paleolithic,” Current Anthropology, 29:2 (1988), 232.

91. Bahn, “Save the Last Trance for Me,” 55.

92. Jack Steinbring, “The Northern Ojibwa Indians: Testing the Universality of the Shamanic/Entropic theory,” in Francfort et al., eds., The Concept of Shamanism, 184. See also Angus R. Quinlan, “Smoke and Mirrors: Rock Art and Shamanism in California and the Great Basin,” in ibid., 189-206, which criticized David Whitley’s version of North American shamanism. For their part, Lewis-Williams and his colleagues have responded in kind. See Jean Clottes and J. David Lewis-Williams, “After the Shamans of Prehistory: Polemics and Responses,” in James D. Keyser, et al., eds., Talking with the Past: The Ethnography of Rock Art, (Portland, Oregon Archeological society, 2006), 100-42; David S. Whitley and James D. Keyser, “Faith in the Past: Debating an Archeology of Shamanism,” Antiquity, 72 (2003), 385-93.

93. This is a large problem and one alluded to above. We cannot examine it on this occasion. Evidence of Voegelin’s concern with consciousness began with his earliest writings; the question of intentional and perceptual consciousness, to be contrasted with non-perceptual or “luminous” and participatory consciousness, was central to his epistolary discussions with Alfred Schütz in the early 1940s; a provisional resolution of the issue is expressed in the title of his 1966 book, Anamnesis.

94. Lewis-Williams, The Mind in the Cave, 7-8.

95. Lewis-Williams, Conceiving God, 23, 27, 117, 131. Lewis-Williams’ colleague, David Whitley, shared this understanding of science. Religious beliefs, he announced, are “unverifiable propositions.” Cave Paintings and the Human Spirit, 198. Such an understanding of “science” and “religion” to a political scientist familiar with Voegelin’s writings on this question is simply parochial nonsense and little more than a symptom, in all likelihood, of the recent origins of archeology and social anthropology. Two succinct formulations of the objection to this understanding of “science” can be found in CW, 5:90-7; and 6: 341-5. Such summary references will have to suffice on this occasion. See, however, Cooper, Eric Voegelin and the Foundations of Modern Political Science, (Columbia, University of Missouri Press, 1999), ch.3.

96. Lewis-Williams and Pearce, Inside the Neolithic Mind, 40. See also Pearson, Shamanism in the Ancient World, 78-90; Whitley, Cave Paintings and the Human Spirit, 39-40, 50.

97. Eliade, Shamanism, 482.

98. Eliade, Shamanism, 485-6.

99. Clottes and Lewis-Williams, The Shamans of Prehistory, 19, 29; Lewis-Williams, The Mind in the Cave, 209-10.

100. See Lewis-Williams and Pearce, Inside the Neolithic Mind, 51-3, 218-23; Lewis-Williams,Conceiving God, 165-8.

101.Here Clottes and Lewis-Williams cited Weston LaBarre, “Hallucinogens and the Shamanic Origin of Religion,” in P. Furst, ed., Flesh of the Gods: The Ritual Use of Hallucinogens, (London, George Allen and Unwin, 1972); Andreas Lommel, The World of the Early Hunters, (London, Everlyn, Adams and Mackay, 1967) as well as Halifax, Shamanism, and Dobkin de Rios, Hallucinogens.

102. Whitley, Cave Paintings, 47.

103. Lewis-Williams, The Mind in the Cave, 151-4; Lewis-Williams, Conceiving God, 144-48.

104. Clottes and Lewis-Williams, The Shamans of Prehistory, 46, 93. But compare König, Am Anfang, 106ff, 231 f.

105. Bahn, “Save the last Trance for Me,” 77.

106. See note 84 above.

107.Lewis-Williams, The Mind in the Cave, 228 ff.

108. Lewis-Williams and Pearce, Inside the Neolithic Mind, 83.

109.Clottes and Lewis-Williams, The Shamans of Prehistory, 48.

110. Clottes and Lewis-Williams, The Shamans of Prehistory, 61.

111.London, Thames and Hudson.

112.LeRoi-Gourhan, Art of Prehistoric Man, 174.

113. The Mind in the Cave, 64.

114. The Mind in the Cave, 65.

115. The Mind in the Cave, 240.

116. J.D. Lewis-Williams and T.A. Dowson, “Through the Veil: San Rock Paintings and the Rock Face,” South Africa Archeological Bulletin, 45 (1990) 5-16. It should come as no surprise that the processural school were unimpressed. See Bahn, “Membrane and Numb Brain: A Close Look at a Recent Claim for Shamanism in Paleolithic art,” Rock Art Research, 14 (1), (1997) 62-68.

117. Lewis-Williams and Pearce, Inside the Neolithic Mind, 120.

118. Lewis-Williams, The Mind in the Cave, 199.

119. Bahn, “Save the last Trance for Me,” 75.

120.Lewis-Williams, The Mind in the Cave, 216ff.

121.Lewis-Williams and Pearce, Inside the Neolithic Mind, 84-6.

122. See however, Lawrence H. Keeley, War Before Civilization, (New York, Oxford University Press, 1996).

123. Voegelin alluded to this complex of problems in a offhand reference to Giorgio de Santillana and Hertha von Dechend, Hamlet’s Mill: An Essay on Myth and the Frame of Time, (New York, Macmillan, 1969). CW, 17: 132.

124.“Ecological and Phenomenological Aspects of Shamanism,” 52. See also Hamayon, “Shamanism: Symbolic System, Human Capability and Western Ideology,” in Francfort et al., eds., The Concept of Shamanism, 6.

125. Francfort, “Art, Archeology, and the Prehistory of Shamanism in Inner Asia,” 249.

126. Bahn, “Save the Last Trance for Me,” 81.

127. Michael Lorblanchet, “Encounters with Shamanism,” 107.

128. See Cooper and Bruhn eds., Voegelin Recollected: Conversations on a Life, (Columbia, University of Missouri Press, 2008), 15ff.

129. Eliade, Shamanism, 507.

This is the second of two parts with part one available here; also available is “Narrative, Neanderthals and Art: An Analysis of Upper Paleolithic Differentiation,” “Human Emergence as Cosmic Metaxy,” “How to Think About Human Origins,” and “From Big Bang to Big Mystery.”