The Origins of Political Science: Leo Strauss’s Analysis of the Thought of Thomas Hobbes in Natural Right and History

Until Thomas Hobbes boldly claimed that his Leviathan was the first true work of political science, most political philosophers had long believed that it was Socrates who deserved the honor of being the first to found the study of politics. After all, it was Socrates who first called philosophy down from the heavens and transformed its focus toward the human things. Whereas the pre-Socratic philosophers were concerned with the motion of the heavenly bodies (the sun, the moon, and the stars) and an examination of the natural and physical world (animal and plant life, as well as the origins of matter and the physical properties of the material things) it was Socrates who first harnessed philosophy to examine such concepts as justice, virtue, ethics, beauty, statesmanship, law, the constitutions of the variety of political regimes, and the duties of citizenship. Also central to Socrates’s thought was the conflict between the philosophical life and the political life, and a number of other topics and dilemmas central to the life of the city or human life within the political society and state.

The drastic transformation of the purpose of philosophy heralded by Socrates, and later by his students, was as important and groundbreaking an intellectual transformation as the changes brought to the study of history by Thucydides, and before him by Herodotus. Previously it was Homer, who in his Iliad and Odyssey had told the tale of Greek history through poetry and myth which attributed causation to the influence of the gods of Olympus over human affairs. Herodotus in his Histories, initiated the move away from Homer and the notion of divine causation as he attempted to base his history of the conflicts between the Greeks and foreign powers, mainly the Persians, through a utilization of historical evidence. The move away from a reliance on the gods as causal agents was effected through Herodotus’s utilization of historical evidence, what he had heard, read or seen about the topics of his book. Thucydides in his History of the Peloponnesian War, took the new science of history further, again refraining from the attribution of causality to the gods or other divine entities.

As a consequence of this development in the methodology of history, Thucydides earned for himself, and for his History of the Peloponnesian War, the designation of the first true work of history in Western civilization, composed by the first true historian. As a consequence, Thucydides continues to be read and studied by students and scholars of history, political theory, and international relations, the best of whom understand there lies within the work of Thucydides crucial lessons about the role of interest, necessity, statesmanship, empire, civil war, national disaster and crisis (such as the plague which ravaged Athens) and a host of other issues at the heart of the study of history and politics which remain salient today.

Given the honor and prestige accorded to these ancient predecessors, one can see just how bold was Hobbes’s assertion that his Leviathan was the first true work of political science. Bold and arrogant was this claim, but nonetheless quite possibly true. In this essay I will examine Hobbes’s claim that he was the founder of political science. I intend to do so via a close reading and analysis of Leo Strauss’s examination of the work of Hobbes in Chapter 5 of Strauss’s Natural Right and History, entitled Modern Natural Right. I hope to show how a transformation from a focus on the duties of man with respect to the political community in which he resides, to a focus on the rights, and more specifically the natural rights of the individual vis a vis the political community in which he lives, is the basis of Hobbes’s claim to be founder of political science with its emphasis on the concept of modern natural right. In so doing I will also, as Strauss has done, briefly examine the influence of Machiavelli on the concept of modern natural right. I will also include a short discussion of how the conflict and discrepancy between rights and duties, which is one of the focal points of Hobbes’s conception of natural right, is central to an analysis of political life and the unrelenting conflicts which characterized the era from which Hobbes emerged as the founder of, at least, “modern” political science.

Around the time that Hobbes wrote, the emergence of modern natural science began to replace teleological natural science, leading to the destruction of the basis of traditional natural right (Strauss 166). Hobbes was the first to recognize the consequences for natural right from this monumental change (166).

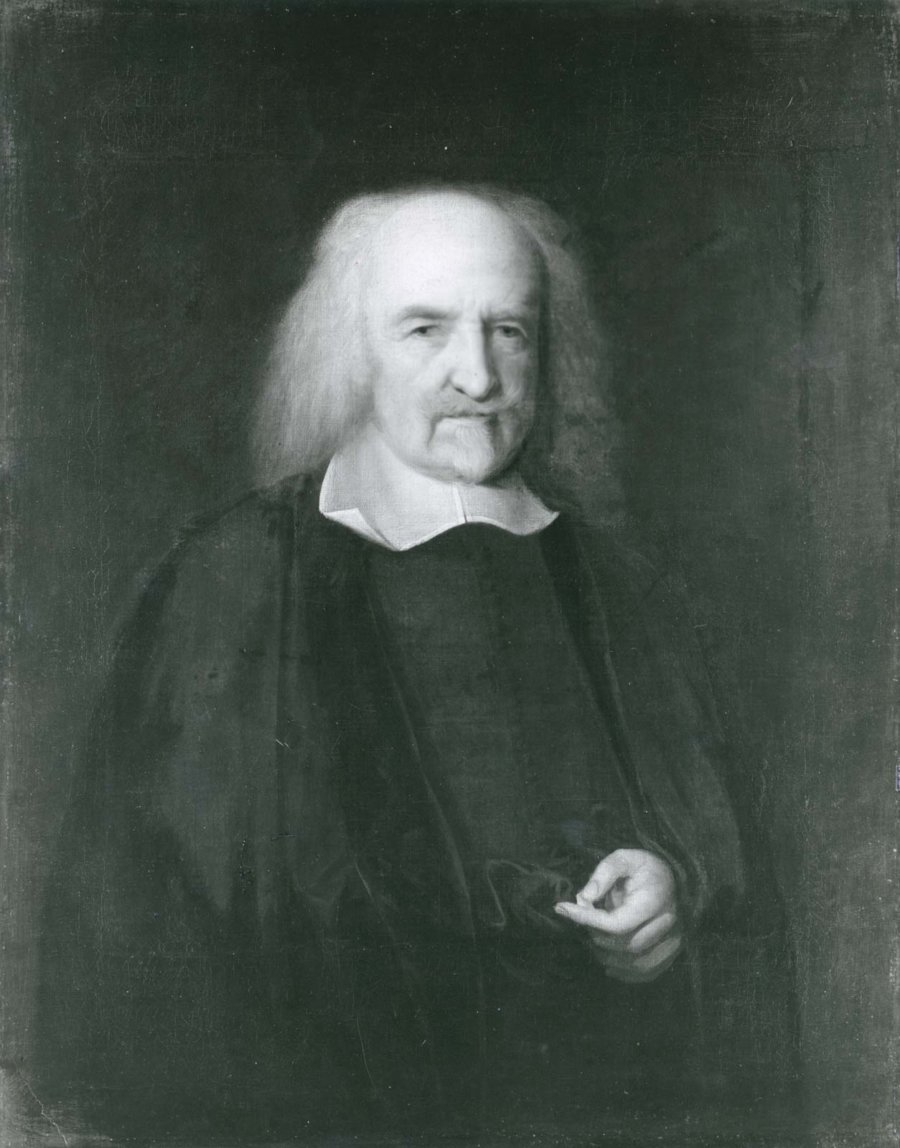

According to Strauss, with regard to this change and its relation to Hobbes’s bold claim to be the originator of political science, Hobbes was impudent, impish, iconoclastic, and extremist. He was the first plebian philosopher, and his almost boyish straightforwardness, never failing humanity, and marvelous clarity and force make him enjoyable as a writer (166). Hobbes was consequently deservedly punished by his countrymen for his recklessness. However, he exercised a great influence on all subsequent political thought, Continental and English. In particular was his influence on the judicious and respectable John Locke, who judiciously refrained as much as he could from mentioning Hobbes’s “justly decried name” (166). However deserving of criticism Hobbes may have been, it is to Hobbes we must turn if we are to understand the specific character of modern natural right (166).

Hobbes, who regarded himself as the founder of political philosophy or political science, was certain that traditional political philosophy was rather a dream than a science. The tradition which awarded the honor of founding political philosophy by almost universal consent to Socrates, was still powerful in the age in which Hobbes wrote (166). Hobbes was indebted to the tradition for a single, but momentous idea. He accepted on trust the view that political philosophy or political science is possible or necessary (167). For this reason, Hobbes was deeply indebted to the tradition he scorned (167).

Hobbes identifies the tradition of political philosophy with a particular movement and an interpretation of the purpose of life within this tradition. The tradition held that the noble and just are fundamentally distinguished from the pleasant and are by nature preferable to it. There is a natural right that is wholly independent of any human compact or convention. There is a best political order which is best because it is according to nature (167). These fundamental tenets of traditional political philosophy were entailed by a quest for the best regime or for the simply just social order. This quest was animated by a political spirit of a particular tradition which was idealistic. (167).

Hobbes did not mention, when writing about the tradition, those thought to be the sophists – Epicurus and Carneades. Because it was ignorant of the very idea of political philosophy as Hobbes understood it, the anti-idealistic tradition simply did not exist for Hobbes as a tradition of political philosophy (168). The problem with the anti-idealistic tradition for Hobbes was that it was not political and not public spirited. Rather than this, the sophists were focused on how the individual could use civil society for his private, non-political purposes; for his ease or for his glory (168). The sophists did not preserve the orientation of statesmen while enlarging their views. The teachings of the sophists were not dedicated to the concern with the right order of society as with something that is choice worthy for its own sake (168). Hobbes, by neglecting to focus on the sophists, identifies traditional political philosophy with the idealistic tradition, thereby expressing his tacit agreement with the idealistic view of the function or scope of political philosophy (168).

Hobbes presents his novel doctrine as the first truly scientific or philosophical treatment of natural law. He agrees with the Socratic tradition in holding the view that political philosophy is concerned with natural right (168). His intention is to show what is law, as Plato, Aristotle, Cicero, and many others have done. Consequently he feared that his Leviathan might remind his readers of Plato’s Republic.

Hobbes’s work differs fundamentally from The Republic because Hobbes rejects the idealistic tradition on the basis of a fundamental agreement with it (168). He intends to succeed where the Socratic tradition had failed (168). According to Hobbes, the failure of the idealistic tradition can be traced to one fundamental mistake: traditional political philosophy assumed that man is by nature a political or social animal (169). By rejecting this assumption, Hobbes joins the Epicurean tradition.

Following the Epicurean tradition, Hobbes contends that man is by nature and originally an a-political and a-social animal. Hobbes also accepts the Epicurean premise that the good is fundamentally identical with the pleasant (169). Hobbes seeks to give a-political views a political meaning by trying to instill the spirit of political realism into the hedonistic outlook. He thus became the creator of political hedonism, a doctrine which has revolutionized human life everywhere on a scale never yet approached by any other teaching. Hobbes modified the hedonistic tradition somewhat by emphasizing self-preservation rather than pleasure, but nonetheless, his break with the Socratic tradition was clear and consequential. This is true even while Hobbes embraced the fundamental Socratic view that political philosophy or political science was possible and necessary (169).

Hobbes’s rejection of the idealistic tradition coincided with his political atheism. This led Edmund Burke to characterize the Hobbesian view as follows: “Boldness formerly was not the character of atheists as such. They were even of a character nearly the reverse; they were formerly like the old Epicureans, rather an unenterprising race. But of late they are grown active, designing, turbulent, and seditious” (169). Strauss adds to Burke’s observation that political atheism is a distinctly modern phenomenon. No pre-modern atheist ever doubted that social life required belief in, and worship of God or gods. Furthermore, political atheism and political hedonism belong together. They arose together in the same moment and in the same mind (169).

Even while Hobbes claimed for himself the honor of originating political science, he regarded Plato as the best of ancient philosophers. This is all the more puzzling because Hobbes’s natural philosophy was more closely aligned with atheistic Epicurean and Democritean physics (169-170). From Plato, Hobbes took the idea that mathematics is “the mother of all natural science.” Being both mathematical and materialistic or mechanistic at the same time, Hobbes’s natural philosophy is a combination of Platonic physics and Epicurean physics (170).

According to Hobbes, pre-modern philosophy or science as a whole was “rather a dream than a science” precisely because it did not think of combining Platonic physics with Epicurean physics, as Hobbes’s natural philosophy did (170). Hobbes’s philosophy was as a whole a classic example of the typically modern combination of political idealism with a materialistic and atheistic view of the whole (170). This combination was a synthesis which melded together two opposed traditions. Strauss suggests that Hobbes may not have been aware of this fact (170).

However, Hobbes was fully aware that his thought presupposed a radical break with all traditional thought. This included the abandonment of the plane on which Platonism and Epicureanism had carried on their secular struggle (170). Leaving this remnant of the past behind and forging new ground, Hobbes, as well as his most illustrious contemporaries, were both overwhelmed and elated by a sense of the complete failure of traditional philosophy (170). Philosophy defined as the quest for wisdom, had not succeeded in transforming itself into wisdom (170-171). Long overdue, this transformation was now to be effected by Hobbes (171).

Regarding the failure of traditional philosophy, Hobbes observed that dogmatic philosophy had always been accompanied by its shadow; skeptical philosophy (171). However, dogmatism had never yet succeeded in overcoming skepticism once and for all. To guarantee the actualization of wisdom means to eradicate skepticism by doing justice to the truth embodied in skepticism (171). For this purpose, one must first give free rein to extreme skepticism. What survives the onslaught of extreme skepticism is the absolutely safe basis of wisdom. The actualization of wisdom is identical with the erection of an absolutely dependable dogmatic edifice constructed on the foundation of extreme skepticism (171).

Of all known scientific pursuits, Hobbes contended that mathematics alone had been successful. The new dogmatic philosophy must therefore be constructed on the pattern of mathematics (171). Consequently, Hobbes was prejudiced against any teleological view and he was in favor of a mechanistic view. The only certain knowledge available is not concerned with ends or purpose. Foremost in Hobbes’s mind was the vison, not of a new type of philosophy or science, but of bodies and their aimless motion (171-172). Precisely because Hobbes was primarily interested in a mechanistic view of the universe, he was inevitably led to the notion of a dogmatic philosophy based on extreme skepticism (172).

“Scientific materialism” could not become possible if one did not first succeed in guaranteeing the possibility of science against the skepticism resulting from materialism (172). Only the anticipatory revolt against a materialistically understood universe could make possible a science of such a universe (172).

Generally stated, we have absolutely certain or scientific knowledge only of those subjects of which we are the causes, or whose construction is in our power or depends on our arbitrary will (173). The construction would not be fully in our power if there were a single step of the construction that is not fully exposed to our supervision. The construction must be conscious construction. It is impossible to know a scientific truth without at the same time knowing that we have made it (173). The world of our constructs is wholly un-enigmatic because we are its sole cause, and hence we have perfect knowledge of its cause (173).

The world of our constructs is therefore the desired island that is exempt from the flux of blind and aimless causation. This world has an absolute beginning and is a creation in the strict sense (173). Hobbes discovery of the “island” of created constructs or its invention permitted an attitude of neutrality or indifference toward the secular conflict between materialism and spiritualism. Hobbes had the earnest desire to be a “metaphysical” materialist. But since this goal proved unobtainable, he was forced to rest satisfied with a methodical materialism (174).

We understand only what we make. Since we do not make the natural beings, they are strictly speaking, unintelligible. This fact is compatible with the possibility of natural science, but it leads to the consequence that natural science is and will always remain fundamentally hypothetical. Our comprehension of the hypothetical character of natural science is all we need to make ourselves the masters and owners of nature (174). The universe will always remain wholly enigmatic, and skepticism is the inevitable outcome of the unintelligible character of the universe, or the unfounded belief in its intelligibility (174).

Hobbes rejects pre-modern nominalism because pre-modern nominalism had faith in the natural working of the human mind (174). According to Hobbes, the natural origin of the universals was a compelling reason in rejecting them in favor of artificial “intellectual tools.” There is no natural harmony between the human mind and the natural universe (175). Humankind can guarantee the actualization of wisdom, since wisdom is identical with free construction of all knowable concepts. But wisdom cannot be free construction if the universe is intelligible. One can guarantee the actualization of wisdom, not in spite of, but because of the fact that the universe is unintelligible (175). Man is sovereign because there is no cosmic support for his humanity. We are forced to be sovereign because we are absolute strangers in the universe. As a result of this, there are no limits to the conquest of nature by humankind. We have nothing to lose but our chains, and perhaps we may have everything to gain (175).

The natural state of humankind is misery. Due to this, the vision of the City of Man to be erected on the ruins of the City of God, is an unsupported hope. Nonetheless, Hobbes remained hopeful even when there was so much cause for despair (175) Strauss reminds us that for ourselves and our contemporaries, the conscious constructs have been replaced by the unplanned workings of “History.” “History” limits our vision in exactly the same way in which conscious constructs limited the vision of Hobbes. “History,” like the constructs, fulfills the function of uplifting the status of humankind and its “world” by making us oblivious to the whole and to eternity (176). The mysterious ground of “History” is the highest principle, which as such, has no relation to any possible cause or causes of the whole (176).

Hobbes’s notion of philosophy or science has its roots in the conviction that a teleological cosmology is impossible, and also in the feeling that a mechanistic cosmology fails to satisfy the requirement of intelligibility (176). Hobbes’s solution to this difficulty was to contend that the end or ends without which no phenomenon can be understood need not be inherent in the phenomena. Instead, the end inherent in the concern with knowledge suffices (176). “Epistemology” becomes the substitute for teleological cosmology, and all intelligibility and meaning has its roots ultimately in human needs (177).

Since the human good becomes the highest principle, political science or social science becomes the most important kind of knowledge, just as Aristotle had predicted (177). This leads Strauss to the observation that Hobbes’s expectation from political philosophy is incomparably greater than the expectation of the classics (177). Hobbes’s philosophy contains no dream illumined by a true vision of the whole, and he reminds his readers of the ultimate futility of all that humankind can do. Of political philosophy thus understood, Hobbes is indeed the founder (177).

Strauss sees the obvious parallels and influences on Hobbes of the thought of Machiavelli. No one of consequence ever doubted that Machiavelli’s study of political matters was public spirited (177). Machiavelli as political philosopher can almost be defined by the phrase “I hold there is no sin but ignorance” (177). Machiavelli combined the idealistic view of the intrinsic nobility of statesmanship with an anti-idealistic view of the origins of mankind and of civil society, if not the whole universe. Machiavelli’s admiration of the political practice of classical antiquity, and especially of republican Rome, is only the reverse side of his rejection of classical political philosophy. He rejected classical political philosophy in the full sense of the term as useless. According to him, the whole tradition of political philosophy was useless (178).

This “realistic” revolt against tradition led to the substitution of patriotism, or merely political virtue, for human excellence, or more particularly for moral virtue and the contemplative life of philosophy. This was a deliberate lowering of the ultimate goal undertaken in order to increase the probability of the attainment of the goal (178).

Just as Hobbes later on abandoned the original meaning of wisdom in order to guarantee the actualization of wisdom, Machiavelli abandoned the original meaning of the good society or of the good life (178). While the good life is an illusive and unobtainable goal, chance or fortune can be conquered by the right kind of leader. Machiavelli’s demand for a “realistic” political philosophy by reflections on the foundations of civil society, ultimately required reflections on the whole within which man lives. According to him there is no superhuman, no natural, support for justice (178). All human things fluctuate too much to permit their subjection to stable principles of justice. Necessity rather than moral purpose determines what, in each case, is the sensible course of action (178-179).

Civil society cannot even aspire to be simply just. All legitimacy has its roots in illegitimacy. All social or moral orders have been established with the help of morally questionable means. Civil society has its roots in injustice rather than in justice. Justice in any sense is possible only after a social order has been established. This means that justice in any sense is only possible within a man-made order (179). Machiavelli believes that the extreme case is more revealing of the roots of civil society, and therefore of its true character, than is the normal case. The root or the efficient cause takes the place of the end or of the purpose (179).

The substitution of merely political virtue for moral virtue presented a difficulty which induced Hobbes to attempt to restore the moral principles of politics that is natural law, on the plane of Machiavelli’s realism (179). Hobbes was aware of the fact that humankind cannot guarantee the actualization of the right social order if it does not have certain or exact knowledge of both the right social order and the conditions of its actualization. This view leads to a rigorous deduction of the natural or moral law. On the basis of Machiavelli’s objection to the utopian teaching of the tradition, Hobbes maintains the idea of the natural law, but he divorces it from the idea of human perfection (180).

Only if natural law can be deduced from how humans actually live, from the most powerful force that actually determines all human action, or most human action most of the time, can natural law be effectual and of practical value (180). The complete basis of natural law must be sought, not in the end of man, but in his beginnings in the state of nature. What is most powerful in most men most of the time is not reason but passion. Natural law will not be effectual if its principles are distrusted by passion or are not agreeable to passion. Natural law must be deduced from the most powerful of all passions.

The most powerful of all passions is the fear of death. More specifically, the most powerful passion is the fear of death at the hands of others. Nature is not the most powerful fear. Instead, “that terrible enemy of nature, death” is the most powerful fear. Yet this death motivates humans as far as they can do something about it; death insofar as it can be avoided or avenged, supplies the ultimate guidance (181). Death takes the place of the telos. The fear of violent death expressed most forcefully the most powerful and most fundamental of the natural desires, the initial desire for self-preservation (181).

Consequently, the most fundamental moral fact, according to Hobbes, is not a duty, but a right. All duties are derivative from the fundamental and inalienable right to self-preservation (181). There are no absolute or unconditional duties; duties are binding only to the extent to which their performance does not endanger our self-preservation. Only the right of self-preservation is unconditional or absolute. By nature, there exists only a perfect right and no perfect duty (181).

The state has the function, not of producing or promoting a virtuous life, but of safeguarding the national right of each individual to self-preservation. The power of the state finds its absolute limit in natural right and in no other moral fact (181). Hence, Hobbes is the founder of liberalism. The fundamental political fact is the rights, as distinguished from the duties of humankind, and the function of the state is the protection or the safeguarding of those rights (181-182).

During the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries there was a shift of emphasis from natural duties to natural rights. The fundamental change from an orientation by natural duties to an orientation by natural rights finds its clearest and most telling expression in the teachings of Hobbes, who squarely made an unconditional natural right the basis of all natural duties, thereby making the duties only conditional (182). Hobbes is the classic exponent of and the founder of the specifically modern natural law doctrine (182).

Hobbes presented a human guaranty for the actualization of the right social order or to his realistic intention. Duties are utopian, but the rights of humankind present a different case. Hobbes’s political philosophy is based on what everyone actually desires anyway. He hallows everyone’s self-interest as everyone sees it or can be easily brought to see it. Men can be more safely depended upon to fight for their rights than to fulfill their duties (183).

Burke noted “The little catechism of the rights of men is soon learned, and the inferences are in the passions” (183). What is required to make modern natural right effective is enlightenment or propaganda rather than moral appeal (183). During the modern period, natural law became much more of a revolutionary force than it had been in the past. This fact is a direct consequence of the fundamental change in the character of the natural law doctrine itself. Hobbes opposed the tradition that assumed man cannot reach the perfection of his nature except in and through civil society, and that therefore civil society is prior to the individual (183). The primary moral fact, according to the tradition is duty, not rights. Hobbes believed that all rights of civil society or of the sovereign are derivative from rights which originally belonged to the individual. There is a state of nature which antedates civil society (183).

Rousseau remarked that “the philosophers who have examined the foundations of civil society have all of them felt the necessity to go back to the state of nature” (183). Strauss noted further that the identification of the pre-political life of man with the state of nature is a particular view, a view by no means held by all political philosophers (184). The state of nature became an essential topic of political philosophy only with Hobbes, who still almost apologized for employing that term (184).

Prior to Hobbes the concept of the “state of nature” was at home in Christian theology rather than in political philosophy. The Christian theologians distinguished the state of nature from the state of grace, and subdivided it into the state of pure nature and the state of fallen nature (184). Hobbes dropped the subdivision and replaced the state of grace by the state of civil society. Through this Hobbes contended that the remedy for the deficiencies or inconveniences of the state of nature was not divine grace, but the right kind of human government (184).

The state of nature was originally characterized by the fact that in it there are perfect rights, but no perfect duties. If everyone has by nature the right to preserve himself, he necessarily has the right to acquire the means required for his self-preservation (185). Hobbes believes everyone is by nature the judge of what are the right means to his self-preservation. This view stands in sharp contrast to the view of the classics which held that the wise decide what is required and necessary, leading to the rule of gentlemen (185).

If everyone, however foolish, is by nature the judge of what is required for his self-preservation, everything may be regarded as required for self-preservation. Everything is by nature just (186). We may speak of a natural right of folly. Consent takes precedence over wisdom. The sovereign is sovereign not because of his wisdom, but because he has been made sovereign by the fundamental compact (186). Command or will, not deliberation or reasoning, is the core of sovereignty. Laws are laws not by virtue of truth or reasonableness, but by virtue of authority alone (186).

The thought of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries in general tended toward a simplification of moral doctrine. One tried to replace the unsystematic multiplicity of irreducible moral virtues by a single virtue or by a single basic virtue from which all other virtues could be deduced (186). Hobbes’s view of Aristotle was that the latter attempted to simplify moral philosophy by reducing morality to either magnanimity or else to justice. The first was done by Descartes, the second by Hobbes. Hobbes’s choice had the following advantage: it was favorable to a further simplification of moral doctrine because it entailed the unqualified identification of the doctrine of virtues with the doctrine of the moral or natural law. The moral law in turn was greatly simplified by being deduced from the natural right of self-preservation (187).

Self-preservation requires peace. The moral law therefore became the sum of rules which have to be obeyed if there is to be peace. Machiavelli reduced virtue to the political virtue of patriotism. Hobbes, in contrast, reduced virtue to the social virtue of peacefulness (187). With this change, justice as virtue undergoes a radical transformation. If the only unconditional moral fact is the natural right of each to his self-preservation, then all obligations to others arise from contract. Justice becomes identical with the habit of fulfilling one’s contract. Justice no longer consists in complying with standards that are independent of human will. All material principles of justice, the rules of commutative and distributive justice or the principle of the Second Table of the Decalogue, cease to have intrinsic validity (187).

The contract that makes possible all other contracts is the social contract or the contract of subjection to the sovereign. Vice becomes identical for all practical purposes with pride or vanity or amour-propre, rather than with dissoluteness or weakness of the soul (188). Virtue comes to mean social virtue or benevolence and kindness – the liberal virtues. The severe virtues of self-restraint lose their standing. This development led Burke to comment on the Parisian philosophers and their influence on the French Revolution. To Burke’s dismay, The Parisian philosophers “explode or render odious or contemptible that class of virtues which restrain the appetite….In the place of all this, they substitute a virtue which they call humanity or benevolence.” Strauss reminds us that this substitution is the core of what is called “political hedonism” (188).

Political hedonism as Hobbes understood it stands in contrast to the nonpolitical hedonism of Epicurus. Hobbes would agree with Epicurus on the following points. The good is fundamentally identical with the pleasant. Virtue is not choice worthy for its own sake, but only with a view to the attainment of pleasure and the avoidance of pain. The desire for honor and glory is utterly vain. Sensual pleasures are preferable to honor or glory (188-189).

Hobbes opposes Epicurus in two crucial points in order to make possible political hedonism. He rejects Epicurus’s implicit denial of a state of nature in the strict sense. There is a pre-political condition of life in which humankind enjoys natural rights. Hobbes agrees with the idealistic tradition in thinking that the claim of civil society stands or falls with the existence of natural right. However, Hobbes rejects the view that happiness requires an “ascetic” style of life and that happiness consists in a state of repose (189).

Epicurus’s high demands on self-restraint were bound to be utopian as far as most men are concerned. These demands had therefore to be discarded by a “realistic” political teaching. Hobbes’s realistic approach forces him to lift all restrictions on the striving for unnecessary sensual pleasures or for power, with the exception of those restrictions that are required for the sake of peace (189). The emancipation of desire for comfort required that science be put in the service of the satisfaction of that desire. The “good life” no longer was the life of human excellence. Rather it became “commodious living” as the reward for hard work (189).

The sacred duty of rulers is no longer “to make citizens good and doers of noble things”, but to “study as much as by laws can be effected to furnish the citizens abundantly with all good things…which are conducive to delectation” (189). Hobbes is the classical exponent of this doctrine of sovereignty. This is a legal doctrine. Its gist is not that it is expedient to assign plentitude of power to the ruling authority, but that this plentitude belongs to the ruling authority as of right. The rights of sovereignty are assigned to the supreme power not on the basis of positive law or general custom, but instead on the basis of natural law (190).

Natural public law represents one of the two characteristically modern forms of political philosophy, the other form being “politics” in the sense of Machiavellian “reason of state.” Both are fundamentally distinguished from classical political philosophy. While the Hobbesian and Machiavellian views are opposed to each other, they are motivated by fundamentally the same spirit. Their origin is the concern with fostering a right or sound order of society whose actualization is probable, if not certain. In addition, the success of this endeavor does not depend on chance. The goal of politics are lowered in order to increase the probability they will be achieved. The “reason of state” replaced the “best regime” by “efficient government.” The natural public law school replaced “the best regime” by “legitimate government” (191).

Classical political philosophy recognized the difference between the best regime and legitimate regimes. The variety of types of legitimate regimes exist due to the differences in circumstances which they must confront. Natural public law, on the other hand, is concerned with that social order whose actualization is possible under all circumstances (191). Hobbes hoped to make possible the just social order which answers the basic practical question once and for all, regardless of place and time. In the view of classical political philosophy, the practical wisdom of the statesman on the spot was required. According to natural public law, there is no longer any need for statesmanship as distinguished from political theory (192).

In the seventeenth century, the sensible flexibility of classical political philosophy gave way to fanatical rigidity and doctrinarism. The political philosopher became more and more indistinguishable from the partisan. The historical thought of the nineteenth century tried to recover for statesmanship that latitude which natural public law had so severely restricted. But because historical thought was absolutely under the spell of modern “realism” it succeeded in destroying natural public law only by destroying in the process all moral principles of politics (192).

Hobbes’s teaching concerning sovereignty is doctrinaire. This is evident by the denial which it implies. Hobbes’s teaching denied the possibility of distinguishing between good and bad regimes (kingship and tyranny, aristocracy and oligarchy, democracy and ochlocracy) as well as the possibility of mixed regimes and the rule of law (192). Hobbes’s doctrine of sovereignty ascribes to the sovereign prince or to the sovereign people an unqualified right to disregard all legal and constitutional limitations. This doctrine also imposes on even sensible people a natural law prohibition against censuring the sovereign and his actions (193).

According to classical political theory, regimes were conceived not so much in terms of institutions as in terms of the aims actually pursued by the community or its leadership. Institutions are only secondary in importance in comparison with education when the aim is virtue (193). From the point of view of natural public law, in contrast, what is needed in order to establish the right social order is not so much the formation of moral character as the devising of the right kind of institutions. Strauss informs us of how Kant viewed this matter. “Hard as it may sound, the problem of establishing the state (i.e.; the just social order) is soluble even for a nation of devils, provided they have sense” (193). Enlightened selfishness is a sufficient basis for the construction of the institutions required to establish a just social order and state. As Hobbes wrote, “When (commonwealths) come to be dissolved, not by external violence, but by intestine disorder, the fault is not in men, as they are the matter, but as they are the makers and orderers of them” (194). Humankind can guarantee the actualization of the right social order because human nature can be conquered through understanding and manipulating the mechanism of the passions (194).

Strauss informs us that the result of the change which Hobbes has effected can be expressed in one word: “power” (194). It is in Hobbes’s political doctrine that power became for the first time a central theme. Science exist for the sake of power. Therefore one may call Hobbes’s whole philosophy the first philosophy of power (194).

“Power” is an ambiguous term which includes both physical power and legal power. Potentia is what man can do, while potestas is the right of man or what man may do. The ambiguity of power is essential. Only if potentia and potestas essentially belong together, can there be a guarantee of the actualization of the right social order. The state is both the greatest human force and the highest human authority. Legal power is irresistible force. The necessary coincidence of the greatest human force and the highest human authority corresponds strictly to the necessary coincidence of the most powerful passion (the fear of violent death) and the most sacred right (the right of self-preservation) (194-195). Physical power as distinguished from the purposes for which it is used is morally neutral, and therefore more amenable to mathematical strictness than its uses. Power can be measured. This explains why Nietzsche, who went beyond Hobbes and declared the will to power to be the essence of reality, conceived of power in terms of “quanta of power” (195).

From the point of legality, the study of ends is replaced by the study of the rights of man or what man may do – potestas. The two kinds of exactness regarding power are mathematical and legal. The sovereign’s rights, as distinguished from the exercise of these rights, permits an exact definition without regard to any unforeseeable circumstances. This kind of exactness is inseparable from moral neutrality. Right declares what is permitted as distinguished from what is honorable (195).

Hobbes’s political doctrine is meant to be universally applicable and hence applicable also and especially in extreme cases. Hobbes built his whole moral and political doctrine on observations concerning the extreme case. This extreme case was the experience of civil war (196). It is in the extreme situation, when the social fabric has completely broken down, that there comes to sight the solid foundation on which every social order must ultimately rest. This is the fear of violent death, which is the strongest force in human life (196).

There are two important phenomena which would seem to show the limited validity of Hobbes’s contention regarding the overwhelming power of the fear of violent death. First, if the individual’s right of self-preservation is the only unconditional moral fact, civil society cannot demand from the individual that he give up that right both by going to war and by submitting to capital punishment (197). A justly condemned murderer retains, and even acquires, the right to kill his guards and everyone else who stands in his way to escape, in order to save his dear life. Hobbes here admitted that there exists an insoluble conflict between the rights of government and the natural right of the individual to self-preservation.

Regarding War, Hobbes proudly declared the he was the first of all who fled at the outbreak of the English Civil War. He was consistent enough to grant that there is allowance to be made for natural timorousness. Hobbes opposes the lupine spirit of Rome. “When armies fight, there is on one side, or both, a running away, yet when they do it not out of treachery, but fear, they are not esteemed to do it unjustly, but dishonorably” (197). By granting this, Hobbes destroyed the moral basis of national defense (197). The only solution which preserves the spirit of Hobbes’s political philosophy is the outlawry of war or the establishment of a world state (197-198).

There remains one fundamental objection to Hobbes’s basic assumption which he strove to overcome. In many cases the fear of violent death proved to be a weaker force than the fear of hellfire or the fear of God (198). The fear of the power of men and the violent death they might inflict is commonly greater than the fear of invisible spirits or religion. However, he also acknowledges that the fear of darkness and ghosts is greater than other fears (198). Hobbes solves the contradiction of these two opposed observations in the following manner. The fear of invisible powers is stronger than the fear of violent death as long as people believe in invisible powers, that is, as long as they are under the spell of delusions about the true character of reality (198). Consequently, the fear of violent death comes fully into its own as soon as people become enlightened.

Hobbes’s whole scheme requires such a radical change of orientation as can be brought about only by the disenchantment of the world, by the diffusion of scientific knowledge, or by popular enlightenment. Hobbes’s is the first doctrine that necessarily and unmistakably points to a thoroughly “enlightened” or a-religious or atheistic society as the solution of the social or political problem. It is only through the prospect of popular enlightenment that Hobbes’s doctrine acquired consistency (198-199). Hobbes ascribes extraordinary virtues to enlightenment. Once the principles of justice are known with mathematical certainty, ambition and avarice, which rest on the false opinions of the vulgar regarding right and wrong, will become powerless. Then the human race will enjoy lasting peace (199).

According to Plato, evil will not cease from the cities until philosophers become kings and philosophy and political power coincide. Plato expected such a solution for mortal nature as can be reasonably be expected from a coincidence over which philosophy has no control. Plato’s solution is one which he can only wish or pray for (199-200).

Hobbes on the other hand, is certain that philosophy itself can bring about the coincidence of philosophy and political power by becoming popularized philosophy and thus public opinion. The point is to establish the right kind of institutions and an enlightened citizen body. Opposing the utopianism of the classics, Hobbes was concerned with a social order whose actualization is probable and even certain. But the right social order does not naturally come about by natural necessity, due to humankind’s ignorance of that order. Humans in their stupidity interfere with the natural order. The “invisible hand” remains ineffectual if it is not supported by the Leviathan, or in other words, by the Wealth of Nations (200-201).

According to Strauss, there is a remarkable parallelism, and an even more remarkable discrepancy between Hobbes’s theoretical philosophy and his practical philosophy. Hobbes teaches that reason is impotent and that it is also omnipotent. Reason is omnipotent because it is impotent. Reason is impotent against passion, but it can become omnipotent if it cooperates with the strongest passion, or if it puts itself in the service of the strongest passion (201). Hobbes’s rationalism rests on the conviction that, thanks to nature’s kindness, the strongest passion can be the origin of large and lasting societies. Hence the strongest passion is the most rational passion. Whereas the philosophy or science of nature remains fundamentally hypothetical, political philosophy rests on a non-hypothetical knowledge of the nature of human beings. The modern contention that humankind can “change the world” or push back nature is not unreasonable. “Humankind can expel nature with a hayfork” (201).

References

Aristotle. David Ross, translator. The Nicomachean Ethics. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 1990.

Aristotle. Steven Everson, editor. The Politics. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1988, 1989, 1990.

Hobbes, Thomas. Introduction by C. B. Macpherson. Leviathan. New York and London: Penguin Books, 1981.

Plato. Raymond Larson, translator and editor. The Republic. Arlington Heights, Illinois: Harlan Davidson Inc., 1979.

Strauss, Leo. Natural Right and History. Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press, 1950, 1953, 1965.

Thucydides. Richard Crawley, translator. Wick, T. E., editor. The Peloponnesian War. New York: Random House, Inc., 1982.