The Stories of the Story-Tellers

One of the most infuriating things about the current history wars is the proclamation that history is “about facts.” Anyone trained in history, especially historiography, knows that history is more than facts—history is the story or the stories we tell about the past which includes facts but includes so much more. History is never dead because it lives with us through the stories we tell of it, and those stories shape our conceptual relationship with history.

During an off hour as an undergraduate at my laptop, completing an assignment in my history capstone course: Historiography, it had become apparent to me that history was more than just names, dates, and events. The dry “facts of history” aren’t that appealing; rather, the stories being told of history were captivating. Having read through the ancient historians and proceeding into the nineteenth century, I distinctly recall an aversion to Leopold von Ranke’s thesis of “wie es eigentlich gewesen” (history as it happened). What is really meant by that idea? For instance, how did Rome actually fall? Read Edward Gibbon and then read Peter Brown and you’ll get two completely different stories, one by a prejudiced fat man and one by a leading scholar of what is now called Late Antiquity, the subject field that I thought I would pursue a doctorate in at the time. Yet, in his life, Gibbon was considered the greatest past master, the eminent historian of ancient history (though he knew little Greek). Now, virtually no one takes him seriously as a eminent or reputable source; someone to read for historiographical influence, yes, but not someone to trust.

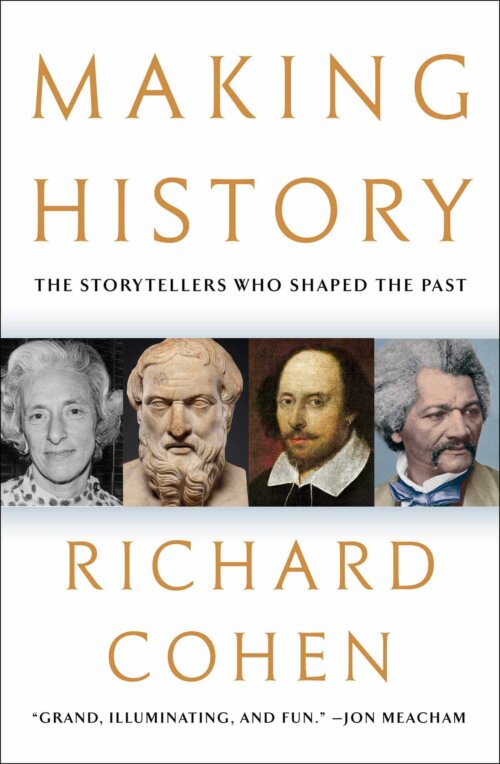

The stories we tell about the past and the storytellers who told them is the story that Richard Cohen tells in Making History: The Storytellers Who Shaped the Past. In this heroic but flawed story of 2,500 years of mythmaking, Cohen peels back the veils that cover the many celebrated historians, writers, even poets and dramatists, who have shaped our consciousness of history. The historian is not only bias in what he or she includes, the historian is bias in what he or she excludes. This became apparent to me during my Historiography lectures too. Historians deliberately select then cultivate their content to tell a story. We, as readers, have always been impressionable by those stories.

Making History begins with Cohen’s own eureka moment while taking history classes at Downside School. His teacher was the rebel Catholic monk and historian Fr. David Knowles, a man spurned and put-down by his own order which left a bad taste in his mouth and soul. When dealing with the dissolution of the monasteries in England, Knowles famously said, ‘They had it coming.’” Hearing this from a Catholic monk was shocking. As Cohen then reflects, “After my schooldays, I began to wonder about other writers who have framed the way we conceive the past.”

Cohen’s broader interest is uncovering why writers have written the way they did? why did they tell the stories they told which we have received and now valorize with the description of history? And so, Cohen begins in the beginning, with the Greeks, looking at Herodotus and Thucydides, and then proceeds to give a whirlwind account of 2500 years of the storytellers who shaped history, from actual historians and politicians to philosophers and dramatists and just about everyone in between.

“Storytellers” is an apt description of the men and women who have shaped our understanding of history. History is not simply “facts,” as the crude retort often proclaims. Facts are otherwise meaningless. We have a conceptual relationships with history. History is part of memory. Memory is part of our consciousness. This conceptual relationship with history is relational.

While Cohen begins with Herodotus and Thucydides, two gentlemen we generally regard as historians, there are myriad of other figures who are covered. Philosophers and sociologists. Dramatists and playwrights. Politicians and social theorists. Generals and social activists. A brief snapshot into the individuals covered may prove illuminating: Herodotus, Polybius, Ibn Khaldun, William Shakespeare, Edward Gibbon, Karl Marx, Ulysses S. Grant, Winston Churchill, Mary Beard, and Ibram Kendi.

Why did these diverse men and women write? Well, there are a lot of reasons. Some were intimately involved in the events they wrote about. Some were winners and others the losers of those events. There is an effort to portray themselves in the best light possible. Others were far removed from the events they wrote about yet ended up impacting our understanding of history more than the historians and writers they drew on in their reimagining. This is true, for instance, of Shakespeare, who gave us the Julius Caesar, Brutus, Antony, and Cleopatra that still has cultural capital instead of Suetonius or Plutarch. But Shakespeare was writing for both money and to help form a new consciousness heading into modernity: the creation of the nation (especially with his English historical plays).

Through Cohen’s panoramic tour of the storytellers of history, we begin to see some of the principal reasons why writers wrote. Rehabilitation. Ambition. Moral Instruction. Ideology. Contemplation. All are among the reasons the storytellers of history wrote their works. The task of the historian, when I was a student as an undergraduate, wasn’t to discover the “objective” historical record. The task of the historian was to become familiar with all the various schools, methodologies, and ways of approaching history. In another word, historiography—the study of the study of history.

While Cohen lacks some of the grace that defined the writers he covers, and while he is guilty of transmitting small scale errors that specialists would roll their eyes at (one also wonders why Harold Bloom would be cited as an authority of the Bible, for instance), the great joy of Cohen’s work is in its easy-reading and broad scope and coverage of the history of history. Even though we may not discover the pure science of history, as Leopold von Ranke believed, Cohen is nevertheless optimistic about how the advancement and changes of historical writing has led to a better understanding of the past. Cohen writes, “[O]ne can reasonably argue that history has advanced over time—that is, those who write or attempt other re-creations of the past are getting better at uncovering and describing what really went on.”

Nevertheless, the problem of our conceptual relationship with “what really went on” returns to the fore. Does history teach us moral instruction? Is history just the product of material and economic forces? Does history bend toward justice? Do “Great Men” move the arc of civilization with their actions? These questions will not be resolved. And that is one of the reasons why we still find history so fascinating and gripping even after all the years, centuries, even millennia, after certain events have occurred.