Has Science Evolved into Technology?

Has science evolved into technology? This question deserves unpacking. “Science” here refers to a modern variant of rationalism, the “autonomous” one that Edmund Husserl bashed as a farce.[1] Now, at first it would seem that science and technology are two distinct enterprises. Science provides an epistemological grounding for technological praxis. Yet, science, as Werner Heisenberg discovered speaking of “today’s physics’ picture of nature,” is about our relationship with nature, rather than nature in and of itself.[2] What this means is that science can no longer be merely Cartesian: it cannot be “merely theoretical.” In fact, modern science never was. But now we have a popular confirmation of what science really is, namely a process by which theory as formal method becomes eminently practical, or as Hegel would put it, “concrete.” Science must then express a progressive synthesis of “subject” (res cogitans) and “object” (res extensa). But that is precisely what technology is. So in effect Heisenberg invites the conclusion that early-modern science is evolving (or should we not rather say, unfolding?) into technology, not, to be sure, as mere-tool, but as a process of integration whereby subjectivity is negated in the act of emerging as what we could call “objective consciousness”—consciousness fully (re)stored in and articulated by its own world/order. Science would then be the technological unfolding of technocracy, the temple of all consciousness, of both reason and imagination/memory.

The mathematician’s notion of science as purely theoretical represents a fading or faded vestige of classical antiquity.[3] In practical terms, today the mathematician is re-articulating a method inscribed in the context of the technological affirmation of technocracy. The method is not providing any concrete knowledge of reality/nature, standing rather as mere steppingstone or tool for our integration as conscious beings into technocracy. The early modern promise of an autonomous mathematics, a mathematics finally emancipated from metaphysics, yields to the affirmation of mathematics as handmaiden to a technological regime in which mathematical formulas are realized/fulfilled in forms of life managed by machines. The life-forms are the formulas themselves, insofar as we are managed in terms of formulas, strands of data, or algorithms. As long as we conceive mathematical formulas as merely-theoretical, free-floating entities we fail to recognize their reality as the concrete content of life-organizing/ruling machines.

Familiarity with Hegel can help us awaken out of the conceptual slumber in which linger all those who still believe that science produces technology at a distance—as if technology were a merely objective entity and modern mathematics a ghost in the machine. Modernity’s “subject” and “object” were never concretely what they seemed to be prima facie. When Descartes “announces” the two poles, he is merely standing at the dawn of a process that the nineteenth century projects unto all ages in terms of History singulare tantum: a universal history aiming “logically” at the affirmation of a universal State/Society.

Hegel’s affirmation through negation, much as Machiavelli’s good through evil, underpins all of the outstanding phenomena of our age: from the identification of techno-tyrannical control with the disinterested securing of freedom, to our loss of identity reified as the discovery of our true identity as defined by a so-called artificial intelligence (AI); from moral and intellectual degeneracy paraded as enlightened/“woke” self-expression, to the conceptualizing of castration in terms of “gender affirmation.”

Historicism has taught us that the abstract is found always in the process of becoming concrete: ideas are to be realized (made-real) historically; put into practice in the interest of the rise of a gloriously free society. It is the apotheosis of freedom that demands that we make strategic use of the past, of the ghosts of our abysmal past, lest we fall haplessly back into their company. “Let us gather the past into a new project that will preserve us, our memory, beyond our death! Let us labor—die—for the Techno-Pyramid in which our ideals are historically consolidated!” Thus rings the call to arms of historicism as it echoes “between the lines” through the corridors of our educational institutions.

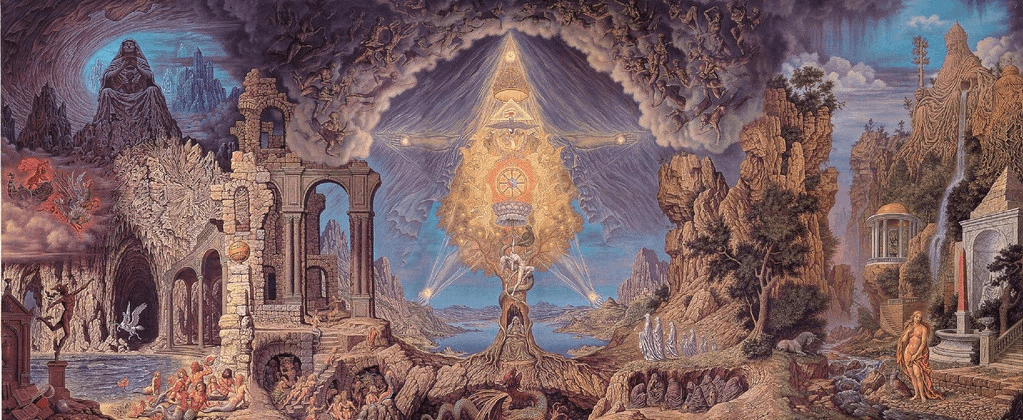

The science of Babel is in the Tower. What the building is purported to show is that all old thoughts were mere shadows anticipating the Tower. Consider, for instance, the ancient notion of atom, Democritus’ indivisible object of contemplation in a mental void. Modernity recycles the atom as an empirical object that, not surprisingly, modern man gradually discovers to be divisible, after all. The empirical symbolic replica of the object of contemplation leads to the obscuring of the unfathomable rift between mind and body, at least as far as our incapacity to raise the latter to the heights of the former is concerned. The new empirical, as Machiavelli’s “new ways and orders” (modi ed ordini nuovi), tends to blind us to the natural primacy of the contemplative over the practical. The alternative on the table involves the conversion of the theoretical into a bodily entity; paradigmatically, God’s Mind into a Tower of Automatons.

Turning back to science we are to find nothing more than a shadow of the latest technology, much as in turning to old religions we are to seek out merely what is useful to us in them. We do not ask which God is the true one, but which one is a best fit for us, inhabitants of the Tower. Which God can best serve as our mascot? Similarly, we ask: what scientific theory can best decorate the hallway of technological empowerment? What banner must our Will to Power uphold, even as it advances to the place where a face-to-face maddening encounter with its own senselessness becomes inevitable?

Should science be more than the shadow of technology? Whether it should or not, we cannot seriously say until we have stepped out of the waters of historicism to ask the Platonic question of what science is in and of itself, or by its very nature. Of course, this difficult question presupposes openness to something permanent, or to nature as realm of substantive permanence. Outside of the stream of technological production, is there anything more than mere ghosts (no matter how transcendentally distilled) begging for inclusion in our brave new world?