Two Kinds of Sacrifice: René Girard’s Analysis of Scapegoating

Mimesis and Scapegoating

Humans are intensely mimetic. We learn to talk, walk, and nearly everything else by imitation. But because we also imitate each other’s desires, other people become our rivals, as we compete for the same things. Taboos and prohibitions can be sufficient to mitigate this problem much of the time, but when there is a crisis, such as a flood, famine, plague, or war, and the social structure based on rules and hierarchies collapses, we find ourselves in a state of horrible equality. The natural hierarchy between a parent and a younger child, or between humans and animals, high status and low status individuals, reduces conflict. In a crisis, each person becomes another’s rival, chaos ensues, and violence breaks out. It is a war of all against all. Without a public justice system, each of us wants to retaliate for the latest offense. If not against you, then against a family member. There is no logical end to the conflict. A common resolution is if we all agree that a single person or a group of people are to blame. This is the scapegoat. We are scandalized by the scapegoat. A “scandal” is etymologically a stumbling block. We are outraged by him. Now it is a war of all against one. Unanimity minus one. Where you find outrage, you will find a scapegoat. The scapegoat is blamed for creating all the problems, all the violence, and they are immolated or ostracized. In lynching or stoning the scapegoat, we all cooperate. Our mutual antagonisms disappear and are temporarily halted with the death of the scapegoat. We bond together in mutual hatred. No one needs to be taught to scapegoat – we do it instinctively. Instead, we actively need to be taught not to scapegoat.

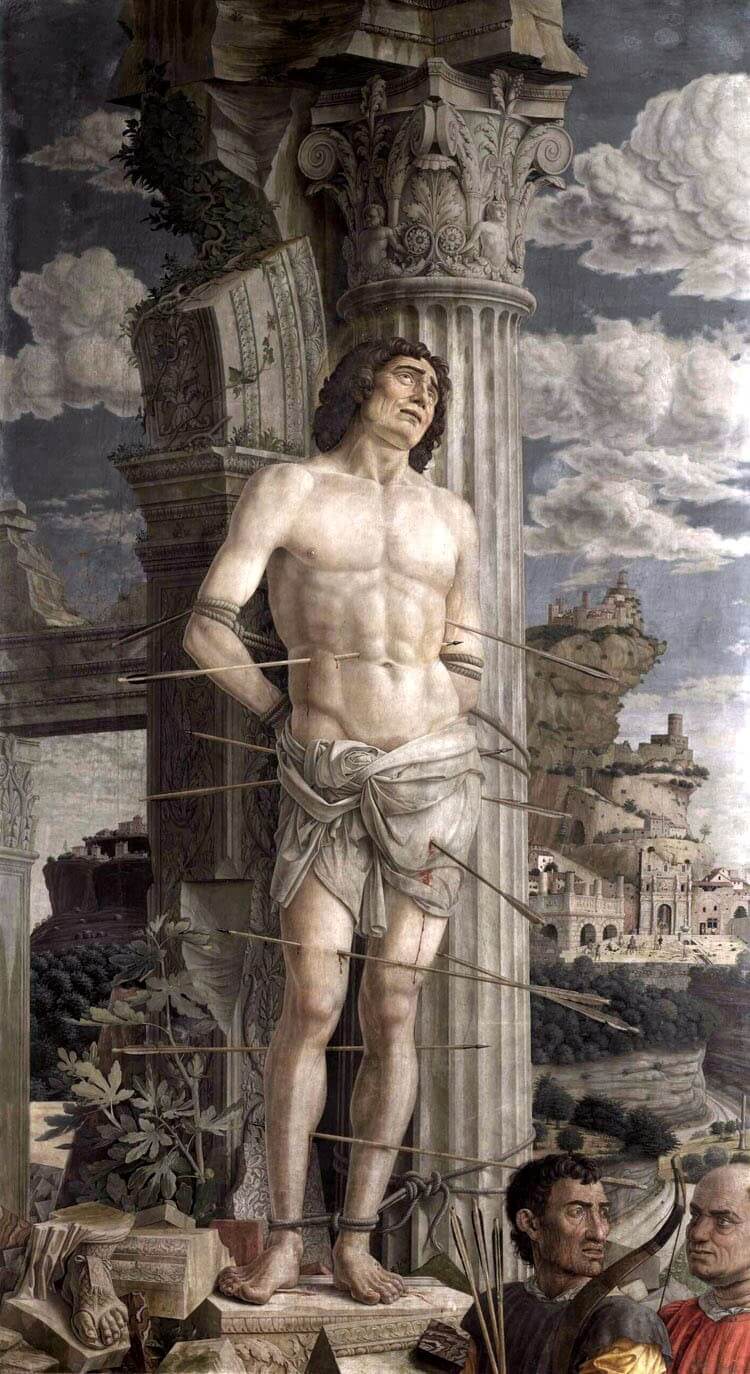

Having been attributed with the diabolical power to create society-wide chaos, a thing it is generally impossible to do singlehandedly, the scapegoat, through his death, has now created peace. And after a while, the “sacrifice” of the scapegoat (murder) is interpreted to be a voluntary renunciation (sacrifice) by the scapegoat – giving up his life to create peace.

The Unfortunate Ambiguity of the Word “Sacrifice” in English

The word “sacrifice” in English has a crucial ambiguity, covering up the difference between the two totally different meanings of sacrifice. In one case, sacrifice is something done to you – the victim is lynched. In another case it involves giving something up, renouncing something. In myths, the scapegoat victim is divinized in retrospective recognition of his sacrifice. Victims are sacrificed – murdered, immolated, lynched. But this is transformed retrospectively in people’s imaginations into self-sacrifice, with the victim supposedly renouncing the desire to continue living, for the sake of the community. The Greeks had two words that are both translated in English as “sacrifice”: thyein, the verb, and thyia, the noun, which means to immolate a victim, literally to make smoke, to honor a god or the gods; and askesis, a noun meaning “to give up something,” to renounce something. These words mark a thoroughly useful distinction and so they must be employed in a careful discussion.

The verb to sacrifice, based on the Latin noun sacer, “something associated with ritual violence,” correctly translates thyein, but not askesis. The mythic lie involves confusing and conflating thyia with askesis and the victim cannot contradict this confusion because he is dead.

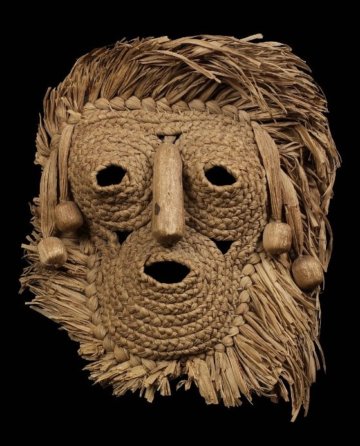

The Corn God

The Iroquois have a myth of the Corn God. His head is shaped as an ear of corn. There is a famine and people are starving, in other words, there is a crisis and the social order has broken down as people get desperate. Chaos and conflict is the result. In the story, the Corn God asks to be killed. He says, “Cut off my head and bury it in the ground and you shall have food.” The people protest saying they love him and do not want to do this. He insists that they kill him, so they do and everyone is grateful. In reality, the Corn God is an ordinary person who has been scapegoated. He or she has been blamed for the violence and stoned to death, or murdered in some other way. The stoning brings the community together – unifying them against a common enemy. This brings an end to the violence directed at each other and satisfies their bloodlust too. Having been attributed with the god-like power to cause a complete breakdown in the social order, the scapegoated victim is now seen to have the similarly divine ability to have brought peace to the community and community is in his debt. The people are grateful to him as a god of peace and “sacrifice” Thyia is now interpreted to be askesis. Sacrifice as a murder is now imagined to be sacrifice as a renunciation – giving up his life.

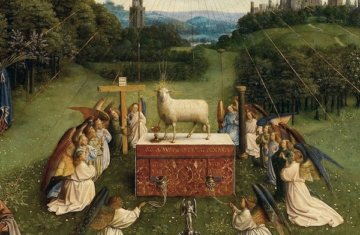

What is likely to strike modern Westerners is the apparent similarity between the Corn God and the crucifixion of Jesus. Positivist anthropologists note the structural resemblances and thus deem Christianity to be just another sacrificial cult. However, what is crucial in Christianity is the interpretation of the events. Myths take the point of view of the mob. The scapegoating mob benefits from the murder and come to express gratitude. The lynching of Jesus, by contrast, takes the point of view of the victim. The scapegoat mechanism is revealed when the innocence of the victim is emphasized and it is recognized that his immolation was murder. Jesus is a sacrifice in both senses of the term. Jesus’ sacrifice (askesis) is to be sacrificed. (thyein). Jesus is reluctantly willing to be lynched if that is God’s will. He says in the Garden of Gethsemane, “Father, if you are willing, take this cup from me; yet not my will, but yours be done.” (Luke 22:42) This quotation reveals that Jesus did not want to die in this manner, but was willing to do it if God wanted him to. God/Jesus died to stop us sinning by revealing the scapegoat mechanism. It is important to note that his immolation cannot make him into a god because, in the story, he is already identified as divine. Jesus is not made God by being crucified. He already was God. In myth, divinization only occurs after the immolation (sacrificial murder).

Myth vs. Religion

All myths are sacrificial. Pre-Christian religions are sacrificial, and thus qualify as myths. Christianity and Judaism are the first actual religions because they reject the mythic sacrificial narrative. Only sacrificial (thyein) or scapegoating narratives exist before 100 AD. These encompass all mythic material. Anti-sacrificial narratives that expose the scapegoating mechanism only exist after 100 AD when Christianity had taken root. This is revelatory or non-scapegoating narrative, which exposes the scapegoating mechanism to view, which Girard sometimes calls anti-myth, though he did not like verbal constructions based on the prefix anti-, as they seemed too mimetic to him. However, sacrificial narrative is not suddenly sent into extinction by revelatory narrative. Scapegoating narratives persist. Virtually all popular narrative and commercial narrative – and politics – is still scapegoating narrative.

Popular movies often have a villain. The villain is the scapegoat of the movie. The scapegoat in the movie may be the individuals being persecuted by the villain. We celebrate the death of the villain and take pleasure in it because it puts a stop to persecution in the movie. But in communally enjoying the murder of the villain we are participating in scapegoating. This super villain sometimes even is threatening to destroy the whole world (e.g., James Bond movies) and thus to be truly satanic and godlike. Sacrificial victims are always considered guilty, satanic villains. We, the audience, are behaving like the fictional villain in the movie who is the scapegoat of the movie. Like all scapegoaters, we scapegoat in good conscience.

Quite often, movies have a supernaturally violent protagonist, like Tom Cruise as Jack Reacher, or Bruce Lee, or revenge movies like The Unforgiven by Clint Eastwood where his character single-handedly murders dozens of men for scarring the face of a woman. In real life, the mob immolates the individual victim. In the movie, the individual immolates the mob. It is still scapegoating – each “bad guy” gets scapegoated (sacrificed/lynched) by the “good guy.”

Satan

Satan is the false accuser who targets the sacrificial victim of scapegoating – the victim who is only imagined to be satanic. Thus, the real Satan casts out the imaginary Satan. In the scapegoat mechanism, unifying the human mob, the victim is killed and thus silenced. The victim cannot tell his side of the story. He cannot rise from the dead to accuse his murderers in turn. Thus Satan covers his tracks – killing the only person who will disagree with the consensus. Scapegoating is always told from the point of view of the beneficiaries of scapegoating, since the crowd survives and the victim can speak no longer. Scapegoating is remarkably efficient – immolation achieves the goal of unity and peace, while killing the one person likely to object.

The faithfulness of the evangelists and the writers of the Gospels means that the lynch mob was not unified. Instead of “all against one,” a minority of witnesses disagreed that Jesus was guilty. They provided written accounts of their contrary point of view. Finally the victim had a voice; had a Paraclete – a defender; the antithesis of Satan. The Holy Spirit is sometimes called the Paraclete. In killing an innocent man, a man already considered divine, who later generations could see was innocent, the unjust and barbaric scapegoat mechanism is revealed for its evilness. Seeking to eradicate the victim and thus dispose of the counter-evidence in the process, Satan instead revealed his diabolical method of unifying the human community. This fact was hidden since the foundation of the world. In fact, it was responsible for the foundation of the human world. We are the beneficiaries of past sacrificial victims who have ended internecine conflict and allowed human communities to persist on the blood of the victims. We should be grateful for their sacrifice (thyia) and unwilling askesis, but we must learn to found human community on the basis of love and acceptance, not murder. If we cannot rise to the challenge of founding and maintaining human communities on love instead of murder, Jesus and God’s revelation of the scapegoating mechanism may mean that violence will just keep on increasing with no way to stop it.

The courage that Jesus’ disciples and defenders exhibited was superhuman. As with everyone who defends the scapegoat, they risked the same punishment, crucifixion, being visited upon them. As well as having nails driven through tissue, the victim’s legs are broken to prevent him from supporting his own weight. Under such circumstances, the victim slowly suffocates; an intentionally horrible way to die. As such, the revelation of the scapegoat mechanism could be considered divine intervention with humans being incapable of discovering it themselves.

The Father out of love, allows his son to be sacrificed, askesis by God, thyia by the human community, the first god to submit to human judgment, to reveal the scapegoat mechanism and thus to put an end to it. Once the innocence of victims is known, killing them has no unifying effect.

The scapegoating and execution of Socrates is similar to the Christian story, however, the scapegoating of Socrates is too calm. He continues a calm conversation with his supporters as he slowly dies from drinking hemlock, losing sensation from the feet up. The Passion of Christ emphasizes the horror. Perception of the significance of the event is lacking if the emotional component is omitted.

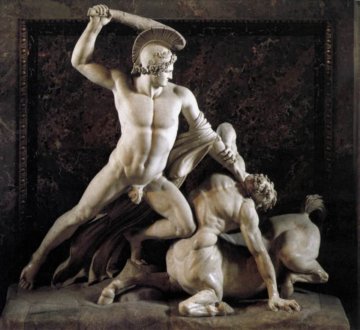

Greek Mythology

All the great heroes of Greek mythology, Theseus, Perseus, Cadmus, Heracles, have a double identity – as a villain of the highest order who has broken major taboos – and as a savior figure. Heracles, Hercules in Latin, is both superman and someone who went mad and killed his entire family. Murdering your own wife and children ranks as a great crime. This dual nature of the savior only makes sense on a sacrificial interpretation. The hero is divinized as a savior, only once he has been condemned to death as a sacrificial victim for having committed gross crimes against the community. The criminal and the condemned gets reinterpreted as savior. As time passed, an attempt was made to clean up the negative side of such heroes.

The hero has the powers of a god. Superhero movies are no different in this regard to ancient myth. But the Greek hero got that way after having been the greatest villain who is sacrificed/immolated.

Why We Do Not Defend Scapegoat Victims

We do not defend scapegoat victims for a number of reasons. One is fear; defending a victim means that there is an excellent chance that you too will be immolated and we are afraid for our lives. Another concerns mimesis; scapegoating occurs when there is unanimity about the guilt of the victim. It is extremely difficult to avoid social conformism. Imagine that all your friends and all your family members concur as to the victim’s guilt. It is likely to be very hard to continue to believe in the victim’s innocence under those conditions. When absolutely everyone disagrees with something important that you believe and for which everyone has seen the evidence, then you might even feel yourself to be mad. The word “idiot” is connected with unique perceptions such as if you were to see little green men that no one else could see. In the famous “line” experiment, it is demonstrated that if a large group of people collaborate in falsely claiming that line A is longer than line B, the one person excluded from this elaborate ruse will also agree that line A is longer, disavowing the evidence of his own eyes. Everyone has found themselves to be wrong when he was very sure that he was right. There is nothing inherently implausible about being wrong about guilt or innocence.

The Judgment of Solomon

The Judgment of Solomon is a Biblical story from 1 Kings 3:16-28. In the story, two prostitutes each claimed a baby was theirs. They came to King Solomon, famous for his wisdom, to solve the dispute. In order to determine who the real mother was, King Solomon suggested cutting the baby in half and giving half to each, reasoning that the real mother would never agree to such a thing. In giving up the child to the other woman, the good prostitute puts an end to their mimetic rivalry, not through the method commanded by Solomon, bloody sacrifice, which the other woman has already accepted, but through love. The good prostitute relinquishes her claim to the object of the rivalry. She does therefore what Christ would have urged her to do: she takes renunciation to its furthest possible extreme, for she renounces that which is dearest to a mother, her own child. Just as Christ died so that humanity might abandon the habit of violent sacrifice, the good prostitute sacrifices her own motherhood so that the child may live. The difference between the good and bad prostitute is erased if we call both a sacrifice.

The good prostitute sacrificed (askesis) agonistic competition for the sake of her child, whereas the bad prostitute agreed to sacrifice (thyia) the child for the sake of the rivalry. When in the heat of agonistic mimesis, winning the competition can start to feel like a matter of life and death. From the outside, it is ridiculous. And it is ridiculous. But my imitating your desire to win, strengthens your desire to win. We each become the mimetic model for the other in a mutually reinforcing feedback loop.

When we feel hurt or insulted, the tendency is to imitate the offensive behavior in the other person, but just that little bit more.

If you hit me in the face, my strongest desire will be to hit you back. In other words, to imitate you. But, in order to teach you a lesson, I will hit you in the face that little bit harder, which will make you hate me even more and make you want to teach me a lesson too. Likewise, if someone cuts you off in traffic, the tendency is to want to do the same thing, but a little bit worse. In this way violence escalates.

This cycle of violence is stopped by someone refusing to imitate – by turning the other cheek and not hitting back: to renounce and sacrifice your desire to retaliate in the name of peace.

The Bible says in not retaliating and in forgiving your enemies, this will heap hot coals on the head of your enemy. You can get them back best, by not getting them back – by not getting angry. This sounds cynical, until it is realized that there are possibly no desires as strong as the desire for revenge; for retaliation. It is not being cynical if the thing being advocated is one of the hardest things to do in the world. It is possible that the rise we see in scapegoating in online culture and late night “comedy” is partly due to anonymity and partly due to the decline of Christianity as a cultural force.

Agnus Dei

Lamb of God, you take away the sin of the world, have mercy on us.

Lamb of God, you take away the sin of the world, have mercy on us.

Lamb of God, you take away the sin of the world, grant us peace.