Are We All Selfish?

Many students imagine that every human being and every action is selfish. Immanuel Kant was rightly suspicious of the tendency to defer everything to the “dear self,” and make ourselves an exception to a rule. However, the idea that everyone is selfish is largely the result of confusions involving language.

Hedonism is the notion that everything we do, we do for pleasure. Aristotle nixed this idea two millennia ago by stating that eating vetch might be the grandest happiness for a cow, but it is hardly sufficient for a human being. If pleasure were the secret of life, it would be possible to install an electrode in the pleasure center of human beings, have a button attached to a battery, and simply press the button for “happiness.” However, most sane individuals reject this scenario as the acme of human flourishing. Such thought experiments involving mechanical devices are simply a variation on the use of heroin. It feels good for a while, but it means nothing, and it prevents most of the things most people consider worthwhile, such as romantic relationships, projects meaningful to the individual, holding down a job, and being self-sufficient, and is likely to cause a premature death. Since heroin is addicting, it also subverts freedom and makes people slaves of a drug.

What many people seem to find convincing is the claim that since being good, kind, and compassionate can feel good, those who are good, kind, and compassionate are actually shameless hedonists seeking pleasure. Mother Teresa gets her kicks from helping the sick and poor, while I do it using crack cocaine; thus, Mother Teresa and “I” are on a moral par: rabidly, and selfishly, pursuing pleasure.

The claim is that everything we do, we do because we imagine we will derive some benefit from it. It would cause most parents significant mental anguish not to help their beloved children in their time of need. So, it is imagined, when a parent gets up at three a.m. to drive his child to the hospital because he is worried about the child’s health, he is doing this in the expectation that he will feel good about his decision and derive some kind of dopamine rush from the exercise. Or, at the very least, he would feel bad about letting his child suffer and perhaps die, and he wants to avoid these unpleasant feelings. However, this conclusion is the result of confused thinking. In order to derive pleasure of any kind from helping someone, it has to be because the person actually loves and cares about that person, which is the opposite of being selfish. The word “selfish” means the exclusive care from one’s own welfare. Loving someone else is the opposite. Enjoying benefiting someone else is only possible if we are not selfish. It is absolutely fine to benefit from being a good, loving person. That has nothing to do with being a selfish person. We do not love “pleasure” per se; we love people, reading, fast cars, stimulating conversations, video games, repairing radios, speculating about the stock market, helping patients, etc.

If Mother Teresa does not actually like and care about the sick and dying, she will not actually derive any pleasure from it. If I do not like fast cars for their own sake, then I will not feel good driving one. Hedonism as a theory, i.e., the notion that everything we do, we do for pleasure. tries to skip the middle man and go straight for the dopamine rush; but the dopamine rush, if in fact that is what it is, is the result of loving something or doing something. It is not the cause of it. The hedonist confuses cause and effect.

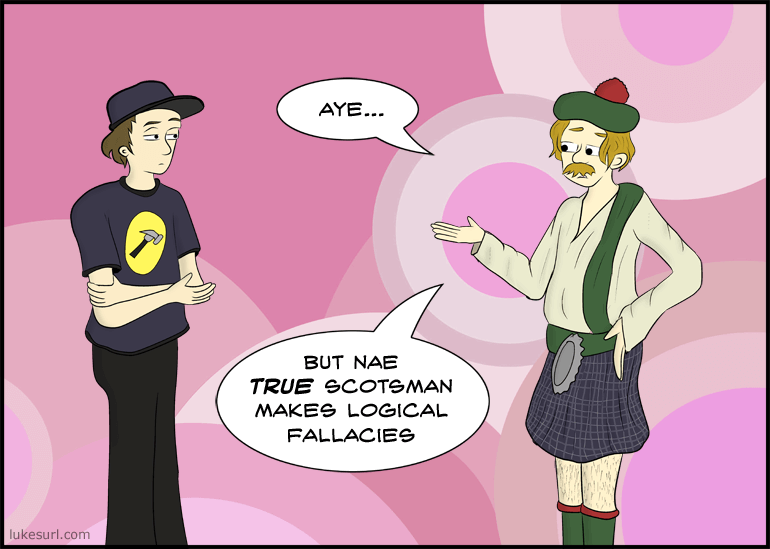

The claim that we are all selfish is an example of the self-sealing fallacy, This is a fallacy where someone makes an empirical (factual) claim, someone else finds a counterexample, and then the first person states that this counterexample does not count because he is not a “real” fill-in-the-blank.

That is why the self-sealing fallacy is most famously called the “no true Scotsman fallacy,” named after a fanciful instance where a Scotsman is reading the newspaper and reads of an awful rape and murder in London. The Scotsman announces that no Scotsman would behave like that, only to find that the rapist and murderer is named Michael Fitzpatrick, whereupon he states that no “true” Scotsman would behave like that.

In the self-sealing fallacy, we begin with an empirical claim. The empirical claim is proven wrong through a single counterexample. The person making the original claim then retreats into tautology. A tautology has to do with the meaning of words; not empirical claims. The most hackneyed example of a tautology is “a bachelor is an unmarried man.” It would be pointless to conduct a study in which every bachelor the researcher encountered was asked if he were unmarried because, thanks to the sheer meaning of the word “bachelor,” all of them will be unmarried. A married bachelor is an outright contradiction.

So, the trick with the self-sealing fallacy is that someone starts with an empirical claim; he is proven wrong by a counterexample, but he tries to salvage his original claim by retreating to a tautology. The apparent benefit of doing so is that tautologies can never be proven wrong. But this is cheating. Empirical claims are claims about the world. Tautologies have to do with the meanings of words. When someone writes that “all men are selfish,” he is claiming to state a fact about the world, about the nature of men. If he simply came right out and said “human beings, as a matter of definition, are selfish” then we would have to contradict him. That is not, in fact, part of the definition of humanity.

Rhetorically, when making factual claims, it is generally not a good idea to use words like “all,” and “never,” since a single counterexample will prove you wrong.

The test of whether someone is making an empirical claim about reality, rather than something true by definition, is if a scenario can be imagined where the supposed empirical claim is false. If I claim that Husain Bolt is the fastest man alive, can you imagine a scenario where this turned out to be false? Yes! If someone called Pete Davies were in fact the fastest man alive. If I say the sun is nine million miles away, under what circumstances would that be false? If it were ten million miles away. If, under no circumstances, you can describe even a hypothetical scenario where your claim would be wrong, then you are not describing something about the world.

If you say “the fact that you did X means that wanted to do it, and we only ever do what we want to do for selfish reasons,” then under what circumstances would you be proven wrong? None. You are claiming that whatever I do, for whatever reason I do it, ultimately I do it because I wanted to do it, and wanting to do something is always the result of wanting pleasure, then no counterexample will ever be possible. You have made it true by definition – not true as a statement about the actual behavior of human beings.

It helps if we get it clear in our minds what “selfish” means. To repeat, it means “exclusive concern for one’s own welfare.” If I derive pleasure from helping other people that is not the same as being selfish. If I were selfish, I would not derive this pleasure. We are allowed to benefit from being a good person. Benefiting from caring about other people does not mean you do not care about other people, which is what being selfish means. I cannot benefit from caring about other people if I do not care about other people – and caring about other people is the opposite of being selfish. If good people derive pleasure from helping other people, and this makes them bad people, then good people are bad people. Then there are just bad people who like helping other people, and bad people who do not! There are loving, caring, bad people, and then horrible, hateful, bad people. You have ruled out the possibility of their being good people.

If we focus on the meaning of the word “selfish,” we will have to agree that not everyone at all times is selfish. Benefiting from caring about other people is not a Catch-22 where we are suddenly become bad people. If there were no benefits from being a good and loving person, the universe would be a very sad place indeed.