Voegelin and Theology Today

A Reflection of 20 Years

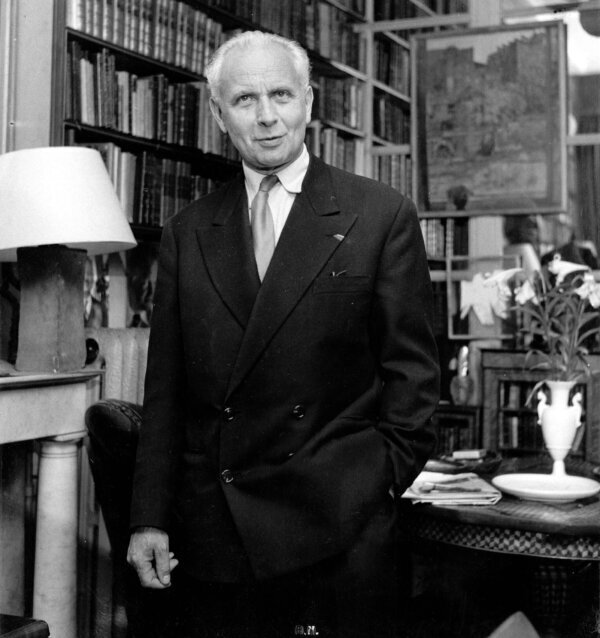

I’ve been asked, in light of the contrasting interpretations of Jürgen Gebhardt and Paul Caringella, and Fred Lawrence’s article that works on reconciling their views, to answer the question whether it is fair or naïve hyperbole to suggest Eric Voegelin as a modern Church Father. As anyone who has attended the annual meetings of the Eric Voegelin Society will know, variations of the Gebhardt/Caringella differences have occurred frequently between some German-born and some North American Voegelin scholars.

An accessible example of these different approaches shows up in the contrasting views of Ellis Sandoz’s “Introduction” and Jürgen Gebhardt’s “Epilogue” to In Search of Order. Fred Lawrence reports the nub of the differences, beginning with a quote from Caringella’s 1994 paper with which Gebhardt strenuously disagreed:

“Voegelin’s ‘New Science’ of order, personal, social and historical order, his philosophy of politics and his philosophy of history, essentially begins and end[s) in the three phases of his meditation over forty years, a meditation that invites and even demands to be placed alongside and studied along with Augustine’s ‘history’ in the phases of its unfolding from the Confessions to the City of God.”

Jürgen Gebhardt took strong exception to the comparison of Voegelin with Augustine, arguing that “Voegelin would have resented being elevated to a modern Church Father.” Moreover, according to Gebhardt, “the reference to Augustine or Thomas very often carries undertones and implications that may cause the nature of Voegelin’s conception of science to be misunderstood.”

While I agree with Lawrence’s profound exploration of the meditative work at the heart of Voegelin’s writing, surely Gebhardt is right to defend the requirement that a work of philosophy such as that in which Voegelin was engaged can only demand of the readers participation by dint of their use of reason, however meditative that may be. Certainly, especially the later Voegelin, emphasized that a hard and fast choice between reason and revelation (which perhaps a Leo Strauss wished to uphold) wasn’t adequate to the philosophic or revelational materials he studied. However Voegelin would hardly have cared to see himself “elevated to a modern Church Father.” While Lawrence sees Gebhardt as too sharply differentiating noetic from pneumatic experience, Gebhardt may in fact be protecting Voegelin’s work from a confessional reading.

Yet Caringella wasn’t calling Voegelin a Church Father, he was primarily focusing on the historiographic and philosophic achievements of Augustine and Aquinas in suggesting Voegelin’s parallel achievement. Considering Voegelin once had no problem lumping together Plato, Machiavelli, Dostoevsky, and Nietzsche as spiritual realists, Voegelin’s own frequent reference to key texts in Augustine and Aquinas hardly amount to a presumption that his readers had to be Christians in order to understand what these Church Fathers were saying. And Voegelin’s last extended interpretation of Weber, his 1964 ‘The Greatness of Max Weber” lecture, focuses less on Weber’s Wissenschaft als Beruf and more on Weber’s greatness in attempting to express his “openness to transcendence and the order of reason and spirit.” (see Hitler and the Germans, CW vol 31, 257 ff, especially 272–73)

A Method and Body of Work for Christian Theologians

Still, I think we can suggest a way in which Voegelin might be considered neither a Church Father, Godfather or grandfather, but as providing both a method of philosophizing and a body of work that are available to Christian theologians if they’re prepared to get involved. As we know, he frequently referred to that passage in the Summa Theologiae where Aquinas developed his understanding of Christ as head of all human beings, from Adam to the last of us to show up in history.

And we remember his exasperated challenge to theologians, if they took Aquinas seriously, to explore the presence of Christ in the full range of human symbolizations of transcendence, from compact to differentiated–we could add also–in the various deformations of these experiences. Then there are his remarks like “History is Christ written large,” and a phrase like “Pleromatic Metaxy,” that surely invite further exploration by Christian intellectuals. Also of course, the repeated drawing on the symbol of exodus as commented on by Augustine in his “he begins to leave [this worldly existence] who begins to love.”

Taken as a whole then–and including the kind of paleolithic to neolithic implications he’d have explored in a “volume zero” of Order and History–both the universal range of experiences he examined, along with his indicating from time to time that its central axis is Christ–Voegelin seems to me to have a role in relation to confessional Christianity that Clement of Alexandria awarded to Greek philosophy: “the same God that furnished both Covenants that of the Law and that of Philosophy was the giver of Greek philosophy to the Greeks, by which the Almighty is glorified among the Greeks.”

But more than merely–however great that merely may be–being an intellectual source for Christian intellectuals, Voegelin has a rugged feeling for universal humanity in all its expressions that rather belatedly found expression in the Catholic Church at the time of the Second Vatican Council, and later in, for example, John Paul II’s magnificent 1986 homily to Australian aborigines in Alice Springs, or his reference to a wide range of civilizations and cultures in the first paragraph of his Encyclical, Faith and Reason:

“. . . a cursory glance at ancient history shows clearly how in different parts of the world, with their different cultures, there arise at the same time the fundamental questions which pervade human life: Who am I? Where have I come from and where am I going? Why is there evil? What is there after this life?”

These are the questions which we find in the sacred writings of Israel, as also in the Veda and the Avesta; we find them in the writings of Confucius and Lao-Tze, and in the preaching of Tirthankara and Buddha; they appear in the poetry of Homer and in the tragedies of Euripides and Sophocles, as they do in the philosophical writings of Plato and Aristotle. They are questions which have their common source in the quest for meaning which has always compelled the human heart. In fact, the answer given to these questions decides the direction which people seek to give to their lives.

In late 1976 I wrote to Voegelin suggesting (not sure how he’d take it, as I knew he didn’t belong to any particular church) that the prayer in St John’s Gospel, “That all may be one,” was something he was helping to bring about at a philosophical level by his reaching out to all of humanity, from the paleolithic period to our own. He replied in a letter of December 21, 1976: “. . . you have gotten the point of my work. If we don’t respect those who have gone before us, who will respect us when we are gone? If we exclude the community of mankind, the community will exclude us.” (CW 30, 816) Again, the response to a believer from a philosopher who interprets the Gospel in philosophical language.

It is interesting that more recent philosophers like Levinas, Derrida, Michel Henry, and Jean-Luc Marion aren’t too bothered about boundary disputes between believing philosophers and philosophers who are not believers.

Voegelin and Lonergan Remain Relevant

Not only philosophy, but also theology has moved on, I’d suggest, without in any way lessening the relevance of Voegelin’s philosophically oriented work or, for that matter, Lonergan’s specifically theological writings on Christ and the Trinity. From Sergei Bulgakov onwards–though among others, Italian philosopher-theologian Piero Coda would go back to Luther and Hegel–there has been a rich exploration of just how that exodus symbol can be enriched in terms of Christ’s kenotic experience of nothingness, expressed in his cry of forsakenness. These contemporaries are increasingly inclined to see that moment of immense inner negation of Christ’s being as a reflection in space-time of the inner dynamism of the Trinity. Then there is the profoundly personal dimension of existence that the later Voegelin leaves for others to explore.

In brief, I find myself in agreement with what I think is a key element in Voegelin’s work that Gebhardt is trying to defend, along with equally fully accepting Caringella’s luminous placing of Voegelin in the company of an Augustine or Aquinas. Their apparent collision had the value of provoking an excellent Aufhebung by Fred Lawrence. My final thoughts above are simply to indicate something Voegelin said at the end of Ellis Sandoz’s symposium on Eric Voegelin’s Thought to the effect that Christianity has gone on for two thousand years, it is impossible for any single scholar to explore it all, please lend me a hand!

Whether Voegelin could ever accept revelation as understood by a believer is a different kind of question that would take a lot longer to unravel.