“What Ish My Nation?”: W.B. Yeats and the Formation of the National Consciousness

There is no great literature without nationality, no great nationality without literature. [1]

-W.B. Yeats

A Nation Once Again

What ish my nation? The rhetorical question posed by Shakespeare’s Irish captain Macmorris in Henry V was prominent in the minds of Irish nationalist leaders during the decades of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. This was a period of intense nationalist activity in Ireland as political events suggested that some form of political autonomy may be in sight for the first time since the original English invasion seven centuries previously. While the English and Irish political class were engaged in parliamentary maneuvering to shape the political institutions to be established, many in Ireland, including W.B. Yeats, were participants in a far more complex debate relating to the definition of that nation. In fact, that debate became even more intense after the derailing of the political initiative in the early 1890’s upon the collapse of the Irish parliamentary bloc with the fall of its leader Charles Stewart Parnell over a sexual scandal.[2] The answer to the question as to what it meant to be an Irish nation was far from self-evident; although Ireland had an identity for more than two millennia as a separate island, it had never been a nation and accordingly any consensus on the constituent elements of a national consciousness was elusive, as Macmorris recognized.

The battle over the meaning of the Irish nation was fundamentally a conflict of ideas, reflecting Hans Kohn’s dictum in his classic treatise on the subject, The Idea of Nationalism: “Nationalism is foremost a state of mind, an act of consciousness.”[3] Yet it is also a state of mind based on some shared experience. As Voegelin has reminded us, “the idea of a community cannot be found anywhere except in the mind of the people belonging to the community and in their intellectual creations. There this idea can be experienced directly in the common structure of the intellectual worlds and persons created by the community in question.” [4]

This article will focus on W.B. Yeats’s efforts to promulgate his idea of the Irish nation as reflected in his poems and plays, prose writings and actions primarily during the approximate 20 year period from 1887 to 1907. His objective was to establish a nationalism based on the ancient Celtic myths, which were the product of a civilization according an extraordinary role to the poet. However, his efforts met substantial resistance in Ireland as this Celticism encountered a competing, and more dominating, tradition in Ireland , one which was derivative at many layers from Rome. Despite the apparent defeat of his Celtic project, as acknowledged in certain poems at the end of this period, his ideas were a major contributor to the events that formed the most enduring myth of the new Irish nation, the Easter Rebellion of 1916, and his reflections on that event in several poems were a principal enabler of that myth. Moreover, Easter 1916 resulted in Yeats becoming an intrinsic part of the myth.[5]

This article will describe the effort of Yeats to form a national consciousness based on the Celtic myths and evaluate the success of the effort. The subject is an interesting one within the context of the study of politics and literature. The works of literature produced by Yeats that will be cited certainly do provide insights about human behavior, aspirations and values, something which typically students of politics and literature look for in studying literary works.[6] However, in the case of Yeats, there are a number of additional dimensions to be considered. First, his literary objectives were not limited to observation; rather, he wanted to mold through literature, not propaganda which he vociferously opposed, a nationalist consciousness, which in turn would contribute to shape human behavior, aspirations and values. Yeats is important also because of the perspective he gained as an active participant in Irish politics during this period. Finally, for his role he looked back to an ancient Irish tradition of the poet being a pre-eminent figure in the political realm. In fact, according to the tales, the greatest of the heroes, such as Cuchulain and Finn, were poets as well as warriors.That was a tradition in stark contrast to the prevailing ones where the poet is “subordinate to the man of action.”[7]

For Yeats and his contemporaries, while there was no defined Irish nation, history presented them with a number of disparate traditions generally corresponding to various epochs : [8] Celtic Ireland, Christian Ireland, Gaelic Ireland, Catholic Ireland, 18th century Parliamentary Ireland and Republican Ireland. Each had its distinct myths with its own set of heroes and ethos. In addition to the diverse traditions represented by these strands, Ireland also was a country whose inhabitants looked back to a multitude of ethnic origins: Irish Gaelic, Norse, Danish, Norman, Spanish, Scottish and English among others.

The first attempt to formulate a concept of the nation through incorporating these motley traditions occurred in the 1840’s by the Young Ireland nationalist movement led by Thomas Davis. More than any other predecessor to Yeats, Davis projected the vision for the concept of the Irish nation, as reflected in the title to one of his most famous of his poems,” A Nation Once Again.” [9] was critical to looks to the past and its symbols to legitimize the present nationalistic aspirations. [10] Davis acknowledged that diverse traditions, ethnicity and religion was a source of conflict. His response was two-fold. The first was to assert that these differences were immaterial since Irishness was an idea. In his poem “Celt and Saxon,” which traces the heritage of the Irish to all these “invaders”, including Celtic and even pre-Celtic ones, he declares: “Yet start not, Irish-born man!/If you’re to Ireland true,/ we heed not blood, nor creed, nor clan–/We have no curse for you.”[11] Secondly, he made an affirmative effort to merge the various strands of Irish tradition in forging a nationalism. For example, his own poems and songs cite representative Irish historical figures from all the Irish traditions. In reflecting upon Davis on the centenary of his birth, Yeats, while acknowledging his poetic limitations, cited his “power of expression” and that he “made himself the foremost moral influence of our politics.”[12]

The other lasting legacy of Davis was his promotion of the role of literature in any nationalist effort, a legacy that was to have a profound effect upon the young Yeats. The journal The Nation published dozens of Irish poets and writers, of which the two most prominent were James Mangan and Samuel Ferguson, who while lacking Davis’ nationalist vision, made their principal contributions to the Young Ireland through the quality of their literary output, particularly those involving traditional mythical figures. [13] The three figures are important to our purposes here not only because of their prominence in the first substantive effort to create the idea of the Irish nation, but as we shall see shortly, they were very much on Yeats’s mind as he endeavored to establish a prominent role in fostering a national consciousness.

A Druid Land, A Druid Tune

That Yeats was very mindful of what he believed to be his prominent, if not pre-eminent, role in the development of Irish nationalism is vividly reflected in his manifesto written at the age of 27, the poem “To Ireland in the Coming Times.” Originally titled “An Apologia addressed to Ireland in the Coming Days,”[14] the poem interweaves the three principal components of Yeats’s nationalism: the role of the poet and by extension literature in the quest for a nation, a nationalist myth based on the ancient Celtic stories and symbols and the recognition of the sphere of the supernatural, whether it be in the form of magic, the occult or religion.[15]

The poem begins with an assertion of his poetic efforts on behalf of the Irish nationalist movement:

Know, that I would accounted be

True brother of a company

That sang, to sweeten Ireland’s wrong,

Ballad and story, rann and song; (VP 137)

With the references to “ballad” and “rann” Yeats immediately introduces us to the ancient Irish literary theme. Rann is the Gaelic word for “verse” and also describes the verse of the ancient Celtic poets.[16] The ballad, whose form originated in the twelfth century in France and was quickly adapted by the Gaelic poets, had been the predominant literary format by the suppressed Gaelic poets during the prior several centuries.

These first four lines also introduce the “apologia” theme of the poem as he asserts that he “would accounted be” among Ireland’s poets to provide service to the nation—“to sweeten Ireland’s wrong.” It is generally believed that a principal reason Yeats wrote the poem was to defend himself against certain critics, including close friends, who had chastised him for his poems being either insufficiently Irish and/or too imbued with esoteric imagery. Accordingly, they believed he was not effectively advancing the Irish cause.[17] He next more directly addresses these critics:

Nor be I any less of them,

Because of the red-rose-bordered hem

Of her, whose history began

Before God made the angelic clan,

Trails all about the written page. (VP 138)

In asserting that esoteric symbols did not detract from his effectiveness, he uses the symbol of the “red-rose bordered hem.” The rose, used pervasively by Yeats in his early works, is one of his more complex symbols. Frequently, it is associated with the occult, particularly because of its role in the Rosicrucian order of the Golden Dawn, leading some to accuse him of making the rose the symbol of his personal occultism. However, Yeats disputed such assertions and claimed that “the rose is a favourite symbol with the Irish poets. It has given a name to more than one poem, both Gaelic and English,” he stated, and is used, “not merely in love poems, but in addresses to Ireland.” In another instance, he noted that the Rose had been for “centuries a symbol of spiritual love and supreme beauty.” Among the Irish poets, he contended, it also had been used variously as a religious symbol, a symbol of woman’s beauty, and a symbol of Ireland. Moreover, based on its use, he speculated that the “Celts associated the Rose with …the goddesses who gave their names to Ireland” or some other principal god or goddesses “for such symbols are not suddenly adopted or invented, but come out of mythology.” (VP 811-12. 842 The other part of the symbol is the “bordered hem,” which furthers the personification of the rose with a woman, which in turn usually represents Ireland, an interpretation that comports with Yeats’s use of this symbol in other works.[18] The identification of the woman with Ireland (and in particular her Celtic past) is further enhanced by his reference to “whose history began/ Before God made the angelic clan.” The poem continues with an exposition of the effect of the rose bordered hem on Irish history. In the “first blossoming age,” the “light fall of her flying feet/ Made Ireland’s heart begin to beat,” an event that has occurred “here and there.”

The opening lines of the second verse set forth the most famous lines of the poem (and certainly one of the more notable of his early career):

Nor may I less be counted one

With Davis, Mangan, Ferguson,

Because, to him who ponders well,

My rhymes more than their rhyming tell

Of the dim wisdoms old and deep,

That God gives unto man in sleep.[19] (VP 138)

One of the more striking aspects of this passage is the audaciousness displayed by Yeats in asserting that not only is he the equal of the three poets but perhaps superior to them. That boldness may not be easily discernible to us who enjoy the historical perspective that has rendered the three poets cited to the ranks of minor Irish poets whereas Yeats stands as one of the pre-eminent poets of the modern age. Such decidedly was not the case in 1892 when the three stood at the pantheon of Irish literature, whereas the young Yeats was struggling to establish himself.[20]

For our purposes, the last four lines whereby he explains why his poetry has an element lacking in his predecessors are the most important of the poem. The references to “ the dim wisdoms old and deep ” and the accompanying lines allude to the principal themes underlying the Yeatsian view of a national consciousness: the existence of an ancient tradition expressed in myths and stories, the remembrance of this tradition, the role of the poet in effecting that remembrance and the presence of the divine in inspiring the poet. [21] These themes will be discussed more fully below. These lines also incorporate another symbol of enormous import to Yeats the poet: the dream imagery. Yeats uses the word “dream “ or one of its grammatical variations approximately 300 times in his poems, of which the vast majority of its occurrences are found in those poems prior to 1916, the date of the last poem that we will discuss. The term has a number of meanings for Yeats , but for our purposes three of those meanings bear much significance: poetic imagination or inspiration, divine revelation and the projection of an ideal. In this passage both the first and the second are obviously present with the allusion to what God gives to man in the “sleep.”[22]

The next several lines comprise a reflection on poetic inspiration as he tells us: “For round about my table go/ The magical powers to and fro/ In flood and fire and clay and wind,/ They huddle from man’s pondering mind.” The use of the word “magical” does suggest the occult, but it is followed by references to the “ancient gaze” and journeying after the red rose bordered hem, clear references to Celtic traditions. The stanza concludes with an emphatic call to Celtic Ireland as it chants: “Ah faeries, dancing under the moon,/ A druid land, a druid tune!” [23] The poem concludes with a reiteration of his poetic mission for Irish nationalism as he understood it: “I cast my heart into my rhymes,/ That you in the dim coming times/ May know how my heart went with them/ After the red rose burdened hem.” (VP 139)

Dim Wisdoms, Old and Deep

The poem certainly acknowledges that Yeats can undertake a traditional poetic role on behalf of the Irish nationalist movement –to sing and “sweeten Ireland’s wrong” through “ballad and story, rann and song.” However, through the reference to the “dim wisdoms, old and deep”, Yeats suggests that there is a more profound aspect to literature’s place in the emerging Irish nation, a theme he expanded upon in his Autobiographies, written nearly thirty years later. He began the discussion with a disclosure of his earlier ambitions: “Might I not with, with health and good luck to aid me, create some new Prometheus Unbound; Patrick or Columbkil, Oisin or Fion, in Prometheus stead; and, instead of Caucasus, Cro-Patric or Ben Bulben? Have not all races had their first unity from a mythology that marries them to rock and hill?”[24] (Autob 166-67) ) He then proceeded to affirm that in Ireland such mythology did exist among the peasants at the time that he wrote the poem.

“We had in Ireland imaginative stories, which the uneducated classes knew and even sang, and might we not make those stories current among the educated classes, rediscovering for the work’s sake what I have called the “applied arts of literature,” the association of literature, that is, with music, speech and dance; and at last, it might be, so deepen the political passion of the nation that all, artist and poet, craftsman and day-labourer would accept a common design? (Autob 167)

In a subsequent passage he again affirmed the goal but also acknowledged the difficulties. “ Nation, races and individual men are unified by an image or bundles of related images, symbolic or evocative of the state of mind,” he boldly asserted, but then he cautioned the reader that “of all states of mind not impossible” such a unified image is “the most difficult to that man, race or nation,” because of the requisite intensity, which is most common in times of war and other events of stress. Nevertheless, because of the existing Irish mythology and events in Ireland, he “had begun to hope, or to half hope, that we might be the first in Europe to seek unity as deliberately as it had been sought by theologian, poet, sculptor, architect, from the eleventh to the thirteenth century.”[25] (Autob 167) Thus, for the 27-year old Yeats, the stakes were high for his enterprise—not only was his poetry to be the midwife of the Irish nation but the nation was to be one grounded in a type of mythology not seen in centuries, one that would avoid what he saw prevalent in the current world, “a bundle of fragments.”

To understand his ambitions, we need to examine the profile of the poet to which he aspired. As we have seen, he wanted to produce an Irish Prometheus Unbound , which would suggest that perhaps we should look to Shelley as his model. Certainly Shelley’s essay “On the Defence of Poetry,” which had been the subject of an essay by Yeats, provided a full-throttled brief on the critical role of poetry in the development of civilization, concluding with the notable lines “poets are the unacknowledged legislators of the world.” Shelley was important to Yeats, but he could not be the model since Shelley was rarely read in his own time. [26] Most tellingly, Shelley referred to his poet legislator as “unacknowledged.” Rather I believe we need to look to the Irish poetic tradition to find Yeats’s model, one that is remarkably more potent than the Shelleyan example.

The Irish poetic tradition, which stretched back about 2500 years was one that Yeats acutely understood. There were three distinct phases comprising that tradition: the ancient Celtic poet or fili commanding immense power and authority in his society, the embattled Gaelic poet of the Irish Middle Ages seeking during the 13th to the 17th centuries to maintain the ancient civilization in the face of the onslaught of invaders of Ireland, most formidably the English, and the popular poet or balladeer who emerged among the peasants following the collapse of the Gaelic civilization in the 17th century. Most significant to our understanding of Yeats is the model of the fili.

Yeats was acutely aware of the pre-eminent power that the poet or fili exercised in Celtic Ireland, which he described in a review in 1889 called “Bardic Ireland”:

“The bards were the most powerful influence in the land, and all manner of superstitious reverence environed on them round. No gift they demanded might be refused them. One king being asked for his eye by a bard in quest of an excuse for rousing the people against him plucked it out and gave it. Their rule was one of fear as much as love. A poem and an incantation were almost the same. A satire could fill a whole country-side with famine.” (UP 63-64)

In that passage, Yeats captured a number of the important characteristics of the bards. They composed two types of verse: the praise poem and the satire. The former conferred legitimacy to the king and his hegemony of the tuatha, the Celtic tribe. At times their role was sacerdotal as they linked the sacred and the profane, particularly in connection with events such as coronations, weddings and deaths. Through their verses, they celebrated and immortalized the battle deeds of the heroic warriors. Conversely, through their satires, they could destroy the king who failed to uphold those kingly ideals, such as generosity and good judgment. They were the only class of people that could move freely from one tribe (tuatha) to another. [27] The poet was an assertive figure whose moral authority transcended the traditional boundaries of government. [28] Morever, as we shall see later, the greatest of the Celtic warriors were also poets.

The final aspect of the poet that needs to be considered is Yeats’s view of the creative process, particularly as it relates to evocation of symbols. In the Apologia, he referred to the “dim wisdom that God gave unto man upon sleep.” With those few words he summarized that which he wrote at length in other forums on the nature of poetic inspiration. In particular, he wrote two essays six and eight years later: “Symbolism in Painting” and “The Symbolism of Poetry.” In the former he declared that “all art that is not mere story-telling, or mere portraiture, is symbolic . . . for it entangles, in complex colours and forms, a part of the Divine Essence.” For him, the best definition of a symbol was the “sign or representation of any moral thing by the images or properties of natural things ” (E&I 146). According to his view, there were similarities between the artist or poet and the “religious and visionary man” with the imagination of both being moved by symbols. He believed there was the systematic mystic “in every poet or painter who delights in…symbolism” and such artists often “fall into trances or waking dreams ” similar to the mystic (E&I 148-49).

In the second essay, the focus turned from the artist to the nature of symbolism itself. He began by observing that for “deliberate artists” there has been a philosophy or criticism “that has evoked their most startling inspiration, calling into outer life some portion of the divine life, or of the buried reality…inspiration has come to them in beautiful startling shapes.” (E&I 154-55). He differentiated between two types of symbols: emotional and intellectual. The former may be a color or a sound “evoke indefinable and yet precise emotions,” but it is the intellectual symbols, which “evoke ideas alone, or ideas mingled with emotions” that are usually referred to as symbols, he asserts. To distinguish the two, he provides the following example. If a poem includes “white” or “purple,” they evoke emotions so exclusively that one cannot say why he is moved. However, if an intellectual symbol such as the cross of a crown of thorns is added to the same sentence, the idea conjured up will be “purity and sovereignty” (E&I 157-161).

In other words, Yeats viewed the poet as drawing from a tradition which incorporated a “buried reality” that participates in the divine. However, as his discussion of the nature of the symbol indicates, there is a second important party to this literary process—the reader.[29] Thus, Yeats was faced with two challenges—to seek out the buried truths of the tradition and then to communicate them in a meaningful manner as the foundations of an Irish consciousness to his late nineteenth century Irish audience.

For Yeats, seeking out the tradition involved a multi-layered exercise of memory, both individual and collective. In his view, there were three principal sources for the tradition: the ancient Celtic myths, the ballads and poems of the Gaelic poets from the twelfth through the eighteenth century and the folk legends and stories passed down through the generations by the peasants. Since each of these sources were oral and relied upon memory, the problems associated with memory such as incompleteness, inconsistency or total forgetfulness. The Celtic myths exemplify the problem. Although Yeats had available written texts for the Celtic myths, those texts fundamentally were the product of memory, which at times had been previously forgotten. The ancient myths originated among the stories of the early Irish inhabitants, probably as early as three centuries BC. For several centuries, they were sung by the fili and transmitted from generation to generation, relying on the memory of the individual poets with respect to not only what each had been taught but also the glosses that they themselves may have added to the stories. The second level of memory emerged during the period that these myths were written down. Encompassing a period of perhaps five centuries, various renditions of the stories were collected by the scribes in the Irish monasteries and ultimately these renditions were coalesced by the thirteenth century into the Old Irish manuscripts bearing such names as Book of Dun Cow, the Book of Leinster and the Yellow Book of Lecan. The tenuousness of this process and the role of remembrance is vividly portrayed in the first chapter of the Celtic epic dealing primarily with the exploits of the warrior Cuchulain, Tain Bo Cualinge. Titled “How the Tain Bo Cuailange Was Found Again,” the chapter opens with “The Poets of Ireland one day were gathered around Senchan Torpeist, to see if they could recall the ‘Tain…’ in its entirety. But they all said they knew only parts of it.”[30]

Most of those manuscripts remained dormant for centuries ( with the result that some stories that had not become part of the oral tradition became forgotten until the nineteenth century when efforts were made by the so-called Celticists to translate them from the Old Irish. One of those translators, Yeats’ collaborator Lady Augusta Gregory commented in her dedication for Cuchulain of Muirthemne: “When I began to gather these stories together, it is of you [her neighbors in Kiltartan where she lived ] I was thinking . . . For although you have not to go far to get stories of Finn and Goll and Oisin from any old person in the place, there is very little of the history of Cuchulain and his friends left in the memory of the people.”[31] Not only was part of the heritage forgotten, but for Gregory and other translators there was the issue of faulty memory. They faced the problem of multiple texts involving different versions of the same stories that had been written at various times by different scribes that frequently were inconsistent or had gaps. [32]

The other two sources, the ballads and folk stories, were more plentiful as they were found in the cottages of the west of Ireland. In his Autobiographies, Yeats described one of his first introduction to faery stories when his grandmother would take him to visit an “old Sligo gentlewoman” while he spent time with the servants listening to their stories (128). Later, he would spend a considerable amount of time visiting the cottages to collect stories from the memory of the peasants, which stories he subsequently published and which also became the source material for his various works. Yet again these stories could vary from locale to locale with it not always being clear what were the original versions.

One of the means that Yeats attempted to overcome these difficulties was through the articulation of his concept of the Great Memory. In his view, the “borders of our memories are …[every] shifting and that our memories are a part of one great memory, the memory of Nature herself,” and that this great memory can “be evoked by symbols.” These symbols may be discerned through visionaries or poets and artists alike. As proof of the existence of this Great Memory “that reveals events and symbols of distant centuries,” Yeats cited examples of visions or images usually reflected in stories by peasants wholly unrelated to the material experience of the person: : “Almost everyone who has ever busied himself with such matters has come upon some new and strange symbol or event, which he has afterwards found in come work he had never read or heard of.” [33] In another context he described symbols the “float up in the mind” whose meanings “one does not perhaps understand for years.” [34] At other times he made reference to the “Anima Mundi, which has a memory independent of embodied individual memories,” and to the “memory of the race, as distinct from living memory” (Autob 210, 213). The enduring role of the Great Memory for Yeats was that it “renews the world and men’s thoughts age after age” (E&I 79). From the ancient memory of the poets in the Celtic past to the individual memory of Yeats as he probed his peasant story tellers, each participating in the Great Memory, there is a consistent thread that reveals the tradition and its symbols, according to the Yeatsian view.

The Celtic tradition was significant to Yeats not only because it could be traced to the “beginning of time in Ireland[35] but also for the principles and ideals that it represented. The meaning of the nationalist struggle to Yeats was reflected in two speeches that he delivered in 1898 and 1904. In criticizing certain aspects of the nationalist movement in the 1890’s in the wake of the fall of Parnell, he commented: “It was utilitarian… and the Celt, never having been meant for utilitarianism, has made a poor business of it.” Continuing, he reflected on why England needed to be opposed:[36]

“We have come to hate them with a nobler hatred. We hate them now because they are evil. We have suffered too long from them, not to understand, that hurry to become rich, that delight in mere bigness, that insolence to the weak are evil and vulgar things. No Irish voice, trusted in Ireland, has been lifted up in praise of that Imperialism which is so popular just now, and is but a more painted and flaunting materialism; because Ireland has taken sides for ever with the poor in the spirit who shall inherit the earth . . . We are building up a nation which shall be moved by noble purposes and to noble ends.”

In the second speech ,[37] he rhetorically asked “What is this nationality we are trying to preserve, this thing that we are fighting English influence to preserve?” For him, the answer was not pride or “national vanity”, but rather the conflict represented “a war between two civilizations, two ideals of life.” Contemporary England to Yeats represented (and continued to do so for the entirety of his life) the embodiment of “materialism,”[38] which essentially represented the liberal tradition—its philosophy and institutions. He objected to its epistemological origins in the writings of Locke and Hobbes and as exemplified in the modern scientific method which he viewed as beginning with Newton. As alluded to in his first speech, he found repulsive the materialism emanating in its philosophy, both in its psychology based on the passions and in its moral theory of utilitarianism, which he saw as predominant in late nineteenth century England . Similarly, the liberal institutions of capitalism and democracy and a society based on the mores of the middle class were seen as reigning amongst Ireland’s overlords.[39]

In contrast, the ideal and norms of the ancient Celts occupied the polar terrain, according to the Yeatsian world view. The ideals of the Celt was perhaps best exemplified by the Achillean-like warrior Cuchulain, the central figure in the Irish epic Tain Bo Cuailinge and about whom Yeats wrote six plays and numerous poems. Cuchulain’s commitment to the heroic ideal is illustrated in a passage in which as a youngster he seeks out to be armed as a warrior. We are told that one day he overheard a druid telling students that the name of whoever took up arms that day for the first time would endure as “greater than any other name in Ireland.” The boy Cuchulain then endeavored to obtain arms by deceit and when discovered by the king and the druid, he was warned that fame and greatness would be achieved but his life would be short. Cuchulain answered forthrightly: “It is little I could care if my life were to last one day and one night only, so long as my name and the story of what I had done would live after me.”[40] That is perhaps as succinct and direct statement of the warrior ethic of greatness as is found in any text. Moreover, no statement could be further removed from an ethics of utilitarianism based on a psychology of seeking to maximize the passions. Cuchulain does die young but his heroic exploits lasted more than a day. His selfless commitment to his King and his subjects is reflected in numerous stories, with his most memorable being to single-handedly defend the province of Ulster against the rest of Ireland for a period of three months. extending over winter while the other warriors were afflicted with the so-called “pangs.” In another battle he kills an intruder who turns out to be his son. There was one additional aspect of Cuchulain that appealed to Yeats—he was a warrior-poet. While wooing his wife Emer, she asks him the source of his strength. He responds that Amergin the poet was his “tutor, so that I can stand up to any man, can make praises for the doings of a king.”[41]

The ancient texts reflect other moral attributes that Yeats valued throughout his life. A principal one of these was generosity. The Celtic kings were to treat their subjects, and particularly their guests, with generosity and if they failed the consequences could be devastating to them and their kingdom as they could be subject to the potentially debilitating satire of the poet. Perhaps the most significant aspect of the Celtic world that Yeats valued was the Celt’s immediacy with nature and the gods. Nature, of course, had been a predominant theme among British poets in the nineteenth century, particularly the Romantic poets prevailing in the earlier part of that century. However, in an essay “The Celtic Element in Literature,” he argued that in contrast to earlier folk literature, the latter poets looked at nature “without ecstasy, but with the affection a man feels for the garden where he has walked daily and thought pleasant thoughts.” Theirs is the view of a “people who have forgotten the ancient religion.” On the other hand, for those whose thoughts were not of “weight and measure ” they “worshipped” nature and its abundance and had a ”supreme ritual that tumultuous dance among the hills or in the depths of woods, where unearthly ecstasy fell upon the dancers. From such a people evolved folk literature that “delights in unbounded and immortal things”(CW IV 129-132).[42] This immediacy with nature was reflected, in Yeats’s view, with a sense of fraternity with the gods. In commenting upon hunter-warriors featured in the so-called Fenian cycle of stories, he observed:

“. . . Finn [the leader of the Fianna warriors] is their equal. He is continually in their houses; he meets with Bodb Dearg and Aengus and Manannan [Celtic gods], now as friend with friend, now as with an enemy he overcomes in battle; and when he has need of their help his messenger can say: “There is not a king’s son or a prince or a leader of the Fianna of Ireland, without having a wife of a mother or a foster-mother or a sweetheart of the Tuatha de Danann.”[43]

There was also a sense of immediacy between the human and the divine, and nature was the intermediary since the gods occupied the principal habitats of nature in Ireland: the mounds, the forests and the rivers. As time progressed, these became known as the habitats of the faeries, the subject of many stories among the Irish peasants, and Yeats was a notorious (in some circles) believer in the faeries.

As we have seen, one of the characteristics of the ancient Celtic religion that attracted Yeats was the sense of magic, as exhibited in the ecstasy and reverence towards nature. His interest in magic and the occult is well documented in his life and his writings. Beginning in his twentieth year and continuing for the next 15 to 20 years he was actively involved in successively the Society for Psychical Research, the Dublin Hermetic Society, the Theosophical Society and the Order of the Golden Dawn. [44] Many of his friends during this period he met through his involvement and with them he engaged in séances and other experiments of the occult. A general discussion of the complex subject of his occult activities is beyond the scope of his paper, and it is its relationship to his nationalism that interests us.

The most significant intersection of the supernatural and nationalism is found in his endeavors to establish an Irish mystical order, which would have had a castle located on an island in Lough Key as a center for its members’ contemplation. In his Autobiographies, he describes his ten year effort to find a philosophy and create a ritual for the order. The philosophy he had hoped would find “manuals of devotion” in imaginative literature and “set before Irishmen for special manual an Irish literature, which, though made by many minds, would seem to be the work of a single mind, and turn our places of beauty or legendary association into holy symbols ” (Autob 204-205) . [45] They conducted visionary experiences of Celtic images and studied the Celtic gods and heroes such as Cuchulain, Deirdre, Fergus and the god Lugh and other members of the Tuatha de Danaan. From these Celtic figures they developed a symbolism based on Cauldron, Stone, Sword and Spear, which were correlated to Pleasure, Power, Courage and Knowledge, important symbols in the tarot card system.[46] Despite the energy invested in the mystical order, Yeats described it as a “vain” effort as he reflected on it 20 years later. Autob. 204.

Sing of Eire and the Ancient Ways

“To Ireland in the Coming Days” is the final poem in a volume called The Rose, published in 1895.[47] The initial poem of the section is “To the Rose upon the Rood of Time” (VP 100) in which Yeats introduces us to the themes of the volume and tells us that he will “sing of Eire and the ancient ways.” If we look at the poems that follow, we find that four deal with Celtic mythology themes, six others are based on various Irish legends or themes, one of which is in the form of a traditional Irish ballad, three focus on the rose symbol, and five involve other themes, including love songs to Maud Gonne. Looking at some of these poems gives us a sense of how Yeats expected his poetry to contribute towards that national consciousness.

The first of the Celtic poems is “Fergus and the Druid” (VP 102), whose subject is the noted figure of the Ulster cycle who gave up the kingship to Conchubar, according to the Tain because of his love for the latter’s mother. Yeats chose not to follow those sources and influenced by Samuel Ferguson’s version of the story (perhaps another example of faulty memory) attributed Fergus’ abdication to his desire to being released from the burden of governing and “to learn the dreaming wisdom.” “A wild and foolish labourer is a king,” he concludes. The Yeatsian Fergus moves into the forest to become a hunter and a poet with druid-like powers—to take up a “bag of dreams.”[48] He is an archetype of the persistent Yeatsian theme: rejection of the material for the spiritual in its various forms, and the poem prominently features the dream symbolism. The second Fergus poem, “Who Goes with Fergus?” (VP 125) describes the former king at the height of his powers in the new world that he aspired to when he abdicated. He “rules the brazen cars,/ . . . the shadows of the wood,/ And the white breast of the dim sea/ And all disheveled wandering stars.” For one who is brooding on “hopes and fears” and “love’s bitter mystery,” Fergus’ example of having thrusting off the burdens of the material should be followed is the Yeatsian message.

“Cuchulain’s Fight with the Sea ” (VP 105) is the first of Yeats’s many poems and plays to deal with Cuchulain and retells the story of Cuchulain’s killing of his son in a battle near the waves in which each is unaware of the identity of his foe. The unwitting son has been sent, under Yeats’s version of the story, by his mother who is upset because Cuchulain has abandoned her; the son heroically is receptive to the mission because he does not want to unheroically “idle life away, a common herd.” Following his discovery of the identity of his vanquished foe, Cuchulain enters into a period of profound mourning, a state that concerns King Conchobar who fears that Cuchulain will rise and slay them all after three days. Conchobar instructs his druids to place magical spells upon the warrior, who upon awakening advances into the sea and “for four days warred he with the bitter tide/ And the waves flowed above Him and he died.” By including the death, which does not occur in the traditional sources, Yeats heightens the tragic nature of the encounter .

The Fergus and Cuchulain poems represent a Yeatsian pattern in drawing upon the old stories. He considers it to be of great importance that the old stories and the embedded symbolism become known by his readers (primarily an educated Dublin audience). On the other hand, he does not hesitate to modify those stories or manipulate the symbols to shape the nationalist consciousness that he is attempting to advance.

Probably the most effective poem of the volume is one which stands among Yeats’s best known and popular, “The Lake Isle of Innisfree” (VP 117):

I will arise and go now, and go to Innisfree,

And a small cabin build there, of clay and wattles made:

Nine bean-rows will I have there, a hive for the honey –bee,

And live alone in the bee-loud glade.

And I shall have some peace there, for peace comes dropping slow,

Dropping from the veils of the morning to where the cricket sings;

There midnight’s all a glimmer, and noon a purple glow,

And evening full of the linnet’s wings.

I will arise and go now, for always night and day

I hear lake water lapping low sounds by the shore;

While I stand on the roadway, or on the pavements grey,

I hear it in the deep heart’s core.

At a first glance, the poem strikes us as a romantic yearning to escape to a Walden-like cabin, and Yeats as a teenager had aspired to imitate Thoreau at Innisfree, a small island in Lough Gill near Sligo.[49] However, as with Thoreau, a closer look reveals a much more radical message. The key to that understanding is found in the last stanza where he tells us that while standing on the “roadway, or on the pavements grey” he hears the lake water and its lapping sounds. The inspiration for the desire occurred therefore when he found himself in an environment that was the antithesis of the west of Ireland, where the isle is situated. London is grey, dirty, crowded, materialistic and non peaceful and it is the center of the opposing civilization to the Irish nation. Innisfree is peaceful, simple, close to nature and non-materialistic. Moreover, to the readers familiar with the Sligo environs, the choice of Innisfree for his cabin would have had additional symbolic meaning. As we learn In a subsequent poem, Innisfree is the situs of the Danaan quicken tree, whose berries according to legends were the food of the faeries. In addition, according to various legends, the berries of the tree either were poisonous or provided the imbiber with extra-mortal powers. The isle therefore was associated as having some special relationship with the Celtic otherworld because of the enchanted tree that grew there.[50] The poem about yearning to retire to the “little rocky Island with a legended past” [51]also reflects an interesting exercise of the Yeatsian poetic method. He tell us that he was inspired to write the poem when he heard a tinkle of water in a shop as he was walking along Fleet St. in London, which led him to remember lake water and “from the sudden remembrance” came the poem reflecting the earlier desire to build a cottage. The memory of the events in his personal life led to an island whose significance had been enhanced by the collective memory of the local inhabitants who had passed down through generations the stories about the enchanted tree. ( Autob 139-140).

His next volume of poems, however, raised some question of whether he had satisfied those lofty goals in his own works that he set out for himself in “To Ireland in the Coming of Times. ” During this period the literary medium that Yeats principally was employing was the lyric poem.[52] The lyric form is the most personal of all literary forms and lends itself, as it did to Yeats, at times to complex and obscure imagery that may be perceived by only a few. In such circumstances, even a poem dealing with traditional Irish themes with admitted objectives of forming a nationalist consciousness could fail because of a general lack of comprehension of its meaning by its readers. Many of the poems found in The Wind Among the Reeds, suffer the fate of obscurantism and hence were understood by few readers.

A good example of this is “The Valley of the Black Pig,” one of the better known of the poems and perhaps one of the more accessible of the volume. The poem reads as follows:

The dews drop slowly and dreams gather: unknown spears

Suddenly hurtle before my dream-awakened eyes;

And then the clash of fallen horsemen and the cries

Of unknown perishing armies beat about my ears

We who still labour by the cromlech on the shore,

The grey cairn on the hill, when day sinks drowned in dew,

Being weary of the world’s empires, bow down to you,

Master of the still stars and of the flaming door. (VP 161)

At first glance the subject of the black pig would appear to be a perfect vehicle for the Yeatsian project of using traditional Irish stories towards the literary formation of a national consciousness. It was based on an ancient Gaelic legend about a battle whereby the black pig and the boar killed the Fenian hero Diarmuid in November in a valley near the imposing mountain Ben Bulben, a few miles outside Sligo. Moreover, according to Yeats’s notes, the Irish peasantry for generations had “comforted themselves in their misfortunes, with visions of a great battle” to be fought in the valley that would free them of their oppressors. In recent years the prophecies had become more frequent and he noted their potential to become a “political force.” The resulting poem, however, is filled with symbols and images that require extensive notes for explanation. Moreover, those notes reveal a meaning not in any manner similar to what we might have anticipated from the tradition of the story. The battle described in the poem, Yeats continued, is one in which the darkness does battle with the light, the winter with the summer and “one between the manifest world and the ancestral darkness at the end of all things” (VP 808-810). Besides being readily intelligible to few, such a message of defeat before the forces of darkness hardly would form the basis of a confident national movement.

Perhaps the most remarkable aspect of the volume were the extensive footnotes explaining the symbols and imagery of the poems. It would appear that we have moved considerably from the Yeatsian definition of the evocative nature of a symbol if footnotes containing long treatise-like expositions on facts and theories of Irish folklore, mystical theories and related topics are required to excavate the symbols in the depths of the poems.

Yeats himself began to question the use of the lyric poem for nationalist objectives, and acknowledgement of its limitations led him to drama. For Yeats, the significance of the drama as a artistic form was its ability to communicate. As he observed, “the one thing I most wish to do is drama & it seems a way, the only way perhaps in which I can get into a direct relation with the Irish public” (Coll. Letters II 416). In reflecting on the contrast between his poetry and drama a few years later, he elaborated on the potential to communicate. In reflecting on the fact that some of the poems of this period had become “unintelligible to the young men in my thought,” he compared himself to a traveler who visits a town and immediately notices the songs of the workmen, the great public buildings and the news of the marketplace, but after several months he lets “his thoughts run” upon a carving on a niche, some Ogham on a stone or the conversation of some who know more about obscure ancient boars than the daily paper. Accordingly he concluded:

“I am half returning to my first ambition, for though I keep my new knowledge in my head, I am no longer writing for a few friends here and there, but am asking my own people to listen, as many as can find their way into the Abbey Theatre . . . Perhaps one can explain in plays, where one has more room than in songs and ballads, even those intricate thoughts, those elaborate emotions, that are one’s self.” (VP 851)[53]

After his completion of the last poem for Wind Among the Reeds, he did not write a lyric poem for a year and it was to be an additional five years before his next volume of poems was to appear, the relatively slim In the Seven Woods, containing only 14 poems of which only two dealt with Celtic themes.

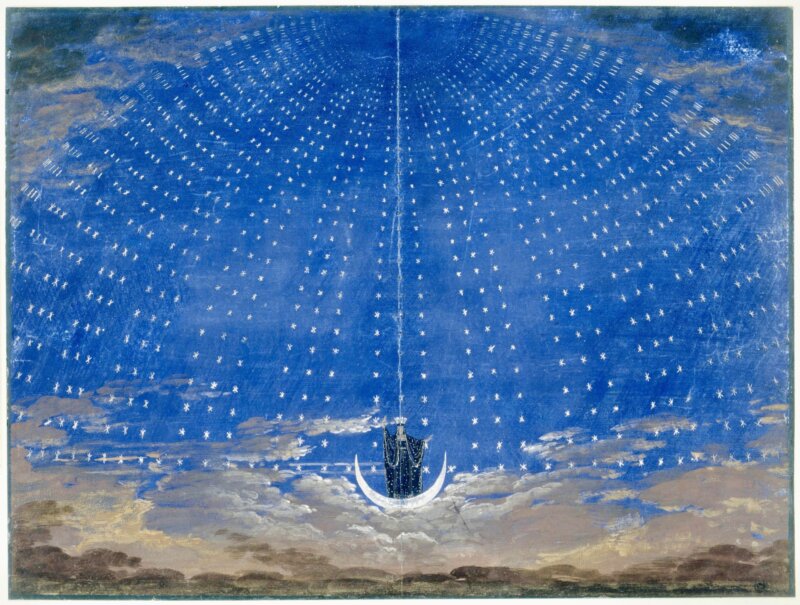

The Irish Literary Theatre (later to become the Abbey Theatre) opened its doors in May 1899 with two productions, including Yeats’s first written play, The Countess Cathleen. (Plays 2) The play, reflecting the traditional Yeatsian themes of self-sacrifice and anti-materialism, focuses on a queen of Ireland during a famine whose subjects sell their souls for food and money to devils disguised as middle class merchants. Cathleen then uses up all her funds to buy the souls back and when she runs out of money agrees with the devil to sacrifice her soul so that her subjects may both eat and save their souls. Despite some criticism from Catholic circles regarding the main theme of selling souls, the opening of the theatre proved to be a successstep in widening the audience of the Yeatsian message. The theatre would prove to be a productive venue for Yeats’s creative output as he wrote 26 plays over his life, including the five Cuchulain plays. The vast majority of his plays dealt with Celtic/ Gaelic themes and/ or were dominated by peasant characters, even long after such matters had disappeared from his poetry The most significant of those plays, and the one that was to have momentous consequences on the Yeatsian project of formation of the national consciousness was Cathleen Ni Houlihan. (Plays 50) [54]

Cathleen Ni Houlihan was not a figure from the ancient Celtic legends but was a common subject of Gaelic songs and stories for a number of centuries although certain elements of her character did have origination in ancient myths. She was principally depicted as a symbol of Irish sovereignty and hence the deliverer of freedom for the oppressed Irish. In a time of political repression, the use of the symbol had serv ed the purpose of disguising the underlying message of the song, story or poem. [55] In addition to utilizing the mythical woman symbolizing Ireland, Yeats also used a historical event that would be known to all Irish, the failed rebellion of 1798 in which the French failed to deliver sufficient forces to enable the Irish to defeat their common foe. The action takes place in Killala, a seaport town in the West of Ireland where the French did land a small force. Thus, there could be no question that the play was burdened with obscure and esoteric imagery recognizable only by a few friends of Yeats . The contrast with The “Valley of the Black Pig” could not be starker.

The focus is on a peasant family, whose son, Michael, is about to enter a marriage economically favorable to him and his family, and much of the early dialogue focuses on the relative merits of a good woman and financial fortune that may be achieved in marriage. In the midst of their conversations, an Old Woman arrives at the cottage . She tells them that “I have traveled far, very far” and “there’s many a one that doesn’t make me welcome.” When questioned as to why she has been wandering so much, she responds that there are “[t]oo many strangers in the house” and that her “land was taken from” her—“[m]y four beautiful green fields.” She notes that many men have died for love of her and “there are some that will die to-morrow ” (Plays 53-54).

She then begins the process of recruiting Michael for her cause of “getting my beautiful fields back again”, but cautions that “[i]f anyone would give me help he must give me himself, he must give me all.” She continues: “It is a hard service they take that help me,” but she reassures him that the potential rewards are immeasurable—immortality through fame:

They shall be remembered for ever,

They shall be alive for ever,

They shall be speaking forever,

The people shall hear them for ever. (Plays 56)

Michael becomes enraptured by her message, and to the dismay of his parents, he departs to join other recruits to rendezvous with the French, who have just arrived. His father Peter goes after him and asks the younger son whether he saw an old woman, and the response is that he did not but “saw a young girl, and she had the walk of a queen ” (Plays 57).

The message of the play is fairly straightforward. It represents another articulation of the themes of rejection of materialistic values, personified in Michael’s parents yearning for middle class status through the marriage, and of the embrace of self sacrifice for a higher cause, in this case nationalist commitment and fame. In doing this Yeats calls upon the memory of his audience in a number of respects. On the most superficial level, there is the memory of 1798, whose heroic failures had been chronicled in dozens of songs and ballads. Moreover, those memories had been recently refreshed in the minds of the Irish with the commemorations of the ’98 centennial , of which Yeats was an organizer. At the next level, we have the symbolism of Cathleen ni Houlihan, who had been celebrated in song and in ballads as the personification of an independent Irish nation. The play also has a number of evocations, some subtle, of the Irish Celtic past. The reference by Cathleen to the four green fields recalls the traditional four kingdoms of Ireland, Ulster, Munster, Leinster and Connacht. The bargain she offers to Michael of heroism and being remembered forever in exchange for a probable sacrifice of his life is reminiscent of Cuchulain’s decision to choose fame over a long life. Finally, the appearance of Cathleen as an old woman who becomes transformed into a beautiful woman is a variation of the “hag” tradition of Irish stories originating in the ancient Celtic tales whereby sleeping with a hag conveys sovereignty to a potential ruler. In most instances, the encounter results in the hag being transformed into a beautiful woman .[56] In addition, the origin of the play is imbued with the Yeatsian “dream,” the source of those “buried realities.” As he wrote to Lady Gregory, “one night I had a dream almost as distinct as a vision” and thought that if he could “write this out as a little play I could make others see my dream.”[57]

As one might expect, the play was enormously successful in nationalist circles, particularly since the message of the nobleness of political sacrifice was delivered by the living female personification of the nationalist movement, Maud Gonne. Others though had some reservations about the implications of the message. George Bernard Shaw commented to Lady Gregory that “when I see the play I feel it might lead a man to do something foolish.” Another observer, Stephen Gwynn, who became a prominent Irish literary scholar, noted that after he saw the original production of the play as a student, “I went home asking myself if such plays should be produced unless one should be prepared for people to go out to shoot and be shot.”[58] As we shall see, these words would prove to be prophetic.

The Celt and Rome

The euphoria following Cathleen was not to last long as the Abbey Theatre’s promotion of the Celtic Ireland of mythology, faeries and peasants was to run headlong into another long established tradition in Ireland with a completely different memory —that which I will refer to as Rome. A hint of this pending conflict first surfaced with Yeats’s Countess Cathleen, which prompted certain objections from Catholic circles over the theme of selling souls. Problems with nationalist groups were to surface, however, not with any of Yeats’s subsequent play, but with those of John M. Synge. Two of Synge’s plays were to create considerably disorder and conflict when produced– In the Shadow of the Glen and Playboy of the Western World. The former play features a woman named Nora living in a remote part of Ireland who is enticed by a fast-talking tramp to leave her older husband who believes that she has been illicitly involved with a younger neighbor. Playboy, which has become one of the classics of Irish drama, revolves around a young man who becomes a hero in a small town in the West of Ireland after he arrives and reveals that he has killed his father, thereby among other things creating a rivalry among the woman in the town for his attachment. The play provoked riots in the theatre when it premiered at the Abbey in January 1907.

The plays generated criticism at three levels among Dublin’s religious, nationalist and intellectual circles, each of which raised significant questions as to the viability of Yeats’s undertaking to establish a nationalist consciousness on the basis of Celtic myths. The first was religious and moral since the behavior of Nora hardly corresponded with traditional Catholic standards. Similarly, the characters of Playboy did not represent the paradigm of the narrow strictures of Irish Catholic morality, and the lightning rod for the in-theatre protestors was the reference by the rogue Christie to “a drift of females standing in their shifts.” Clearly, much criticism was leveled at the plays from this perspective, and the views of the Church clearly had to be taken into account by any institution attempting to establish itself in Dublin at this time. However, the theatre had survived the Church’s assault on Countess Cathleen and ultimately it needs to be concluded that the criticism from this quarter was not a major threat.

More potent were the critiques from the political nationalists, particularly Arthur Griffith , who had been a strong ally of Yeats, a board member of the Theatre at one point and an effective opponent of the Catholic critics of Countess Cathleen . Griffith had earlier expressed his view of the national theatre:

“We look to the Irish National Theatre primarily as a means of regenerating the country. The Theatre is a powerful agent in the building up of a nation. When it is in foreign and hostile hands, it is a deadly danger to the country . . . In the Ireland we foresee it will be an extremely dangerous thing to tell an Irishman that God made him unfit to be master in his own land.”[59]

Another observer, the labor leader James Connolly echoed these themes when he declared that the national theatre should be supportive of “the forces of virile Nationalism” and not “decadence” and should have as its primary focus the objective of “restoring our national pride.” In other words, these nationalist leaders sought a theatre that would portray the Irish people positively before English opinion (those of the “foreign and hostile hands”) ; and have a beneficial effect on the self-perception of the Irish. For the political nationalists, these were critical points because they bore on the likelihood of success of the project of establishing and maintaining a nation. With their position, these nationalists were driving a stake through the central premise of the Yeatsian vision. Theirs was not to be a nation of peasants, faeries and Celtic mythological heroes. Rather, theirs was to be one formed around the ideals and norms of the English and other European democracies with values emanating from the Enlightenment. It was to be a nation of middle class aspirations populated by the characters of James Joyce’s novels and short stories and not the Abbey Theatre’s peasants.

This dissatisfaction with the peasant plays also was expressed by other critics, beginning with Joyce himself. In his early essay, “The Day of the Rabblement,” published in 1901 when the Theatre movement was only a couple of years old, he advanced his thesis that the Irish Theatre should be looking to European inspiration (particularly Ibsen) rather than the tales of Irish peasants. In his view, “a nation which never advanced as far as a miracle-play affords no literary model to the artist, and he must look abroad.” [60] These views were echoed by Thomas Kettle, one of Joyce’s university contemporaries: “If this generation has for its first task the recovery of the old Ireland, it has for its second, the discovery of the new Europe . . . My only counsel to Ireland is, that in order to become deeply Irish, she must become European.”[61]

The common element in these criticisms, I believe, is Rome, representing not only the Church but also the political and intellectual traditions of the European Enlightment. To understand the tensions in Ireland, we need again to delve briefly into Irish history, for the origins of the Celt and Rome conflict stretched back to the fifth century. The Christianization of Ireland represented most significantly the first “invasion” of Ireland in about 800 years or so. The western borders of the Roman Empire had stretched only as far as England with the result that the Celtic culture remained for the most part untouched by the encompassing Roman way of life.[62] Patrick and his associates were to become the vanguard in this effort to impose upon the Celts what had been accomplished through the force of arms in much of Europe—a culture based on Roman ideals. The subsequent history of Ireland can be viewed, I believe, as a continuing clash between the Celt and Rome—one that persisted precisely because the original Roman intrusion was nonviolent.

The early Christian leaders did make a concerted effort to synthesize the Celtic and the Christian traditions. For example, the Celtic feast days became Christian with, for example, All Saints Day replacing Samhain on November 1. Literary works during this period often reflected this attempt at synthesis. Perhaps the most remarkable extant example of such is the endeavor to transform Christ into a Celtic hero, as set forth in two poems by an eighth century writer.[63]

Despite these efforts of integration, fissures developed as the Celts proved to be less pliant in assuming Roman aspects of the religion. In particular, the evolving primacy of the monastery abbots over the diocesan bishops struck more at the heart of the Roman structure of the Church. The urban-centered diocese, which had evolved from a similar Roman institution and the foundation of its administrative apparatus, was ill-suited for the almost exclusively rural society based on tribal authority (the tuatha) of Ireland. Consequently, the monasteries, institutions considerably more conducive to the Irish way of life, became the depositories of authority. A contemporary commentary of the power of the monasteries frequently cited is the eighth century historian Bede’s description of Iona: “This island, however, is accustomed to have an abbot in priest’s orders as its head, so that both the entire province and also the bishops themselves are required, by an unusual ordering of affairs, to be subject to his authority. This is in accordance with the example of Iona’s first teacher, who was not a bishop but a priest and a monk.”[64]

For the next several centuries, the Church in Ireland continued this trend of its independent ways, which at times raised alarm in Rome. This concern with the Celtic church reached its height during the papacy of Adrian IV, the only Englishman to be elected pope, who issued a Papal Bull Laudabiliter declaring that the English king, Henry II had jurisdiction over Ireland. The language of the Bull is instructive in revealing Rome’s view towards its relationship to the Church in Ireland. Adrian was granted the authority to conquer Ireland “for the enlarging of the bounds of the Church,” and this was effected by the first English invasion of Ireland in 1167 led by the Norman earl, Strongbow.[65] Following the successes in the southeastern part of Ireland, Henry II caused the convening of the synod of Cashel in 1171, which dealt a considerable blow to the Irish monastery system and proclaimed that the Irish Church, at least in name, was subject to Rome.

While the monasteries were weakened, in general, the Church met with limited success in Romanizing the population because the native Irish proved to be far more proficient in influencing the Norman settlers, who soon became indistinguishable from the Gaels in their customs. Two centuries after the first invasion when the English hold on the small portion of Ireland that it purportedly controlled, the so-called Pale, was tenuous, the Statute of Kilkenny were enacted to curb the Gaelicization of the English. It was a blunt instrument with such provisions as prohibiting intermarriage, requiring that no Irish be admitted into English churches and forbidding Irish minstrels or storytellers (the bards) from entering English territory. The perhaps unintended effect of these laws promoting rigid separation was to strengthen the Gaelic culture, which was further enhanced by the fact that the numerous battles in Ireland during the next couple of centuries waged by the English crown were generally confined to efforts to subdue the descendants of the Norman settlers. The Gaelic culture was minimally affected by the English culture, the manifestation of Rome on the British Isles.

The Reformation, of course, was to cause a deep fissure between England and Rome and the subsequent battles in Ireland waged by Henry VIII, Elizabeth, Cromwell and William of Orange were to result in the destruction of the old Gaelic order. The religious wars led to the Gaels seeking closer relations with Rome and putative alliances with her French and Spanish allies. Ultimately, when the Penal Acts were enacted preventing the education of Catholics in Ireland, the education of Irish Catholics occurred at Continental schools in France, Spain and Italy with the result that the Celtic tradition was largely absent among the educated Catholics in Ireland. During this period, the Celtic was preserved by the travelling balladeers and the peasants in the West of Ireland. Upon the final elimination of the vestiges of the Penal Acts and the affording of certain privileges to the Catholic Church in the Union Act of 1800, the hold of Rome and its traditions on the educated Catholics become more secure. The urban Dublin audience of the Abbey, such as Kettle and Joyce, were the product of the education in the Catholic schools and universities that evolved following these political developments.

Yeats of course was aware of the chasm between the Celtic and Roman traditions. One of his earliest works, the epic-like Wanderings of Oisin is centered around a conversation between St. Patrick and Oisin, one of the last Fenian warriors who has returned after 300 years of wandering . Upon his return, Oisin finds that nearly all his fellow warriors are dead and the Christianity has come to Ireland destroying the old warrior culture. St. Patrick advises Oisin that he should kneel down and pray for his soul since “on the flaming stones, without refuge, the limbs of the Fenians are tost.” Oisin rejects this bid to convert and the poem concludes with his affirmation of the old pagan culture of Ireland: “I will go to Caoilte, and Conan, and Bran, Sceolan, Lomair/ And dwell in the house of the Fenians, be they in flames or at feast ” (VP 62-63). While not exhibiting Oisin’s stance of defiance, the contemporary Irish peasants, in Yeats’s view, similarly embraced pagan Celticism.

In an article published in early 1898, he wrote that “none among people visiting Ireland, and few among the people of Ireland, except peasants, understand that the peasants believe in their ancient gods, and that to them, as to their forbears everything is inhabited and mysterious.”[66] He continued that even after twelve centuries of Christianity they still believed that the “best of their dead” are among the raths and twisted thorn trees where the gods reside. Besides the affirmation of the paganism of the peasants, the other remarkable aspect of this passage is the implied criticism of the non-peasants of Ireland for not recognizing this phenomenon. This critique was more pointed and directed towards the stewards of the Roman tradition in Ireland in an earlier essay: “Nothing shows more how blind educated Ireland—I am not certain that I should call so unimaginative a thing education—is about peasant Ireland, than that it does not understand how the old religion…lives side by side with the new religion ….”[67] Later he commented that the Irish peasant had “invented…a vague though not altogether unphilosophical, reconciliation between his Paganism and his Christianity.”[68] This posture of the peasants was akin to that of the early Irish church, in his view, where it was difficult to discern “where Christianity begins and Druidism ends.”[69] However, the centuries of Roman infiltration was to have an enduring impact on Ireland to the detriment of the Celt, particularly since those of the Roman tradition controlled the principal educational and religious institutions and were beginning to acquire hegemony over the political and literary in Ireland. Whether it was through those with a direct line of tradition to Rome such as the Catholic Church or those who were heirs of rebellion against Rome but still remainedbroadly within the tradition such as Protestants, scientists, republicans in politics, middle class merchants (increasingly Catholic) or the intellectuals captured by the European literary tradition, the challenges to Yeatsian Celticism were formidable.

Yeats himself ultimately bowed to this reality and by the beginning of the second decade of the twentieth century, the Celtic had for the most part disappeared from his works. His public acknowledgment of this defeat is revealed in his short poem written in 1912, “A Coat”, in which he acknowledged that previously “I made my song a coat/ Covered with embroideries/Out of old mythologies/From heel to throat.” He declared he was abandoning that coat since “ there’s more enterprise/In walking naked ” (VP 320). Not coincidentally, this poem was contemporaneous with certain other events that were to crystallize into a profound and emotional disillusionment reflected in his poem “September 1913,” one which could have been viewed as a valedictory announcing his withdrawal from public affairs.

The poem is perhaps best known for its ballad refrain, “Romantic Ireland is dead and gone,/ It’s with O’Leary in the grave ” (VP 289) with the reference to the legendary nationalist leader strongly suggesting that any noble nationalist aims had vanished. For the most part though, the poem lacks direct allusions to the Celtic ideals and in fact points to heroes from later periods to upbraid the contemporary Irish for failure to adhere to heroic standards. However, the Celtic is not entirely missing from the poem. There definitely are echoes of the ancient satire poem as the Irish people are rebuked for their lack of heroism and generosity. In fact, one of the most prominent symbols in the poem recalls one used in the generally considered the first satire in Ireland. Yeats begins the poem: “What need you, being come to sense,/ But fumble in a greasy till” (VP 289). In the old story, one of the complaints of the Tuatha de Danaan against the soon to be deposed king Bres was that “their knives never were greased in his house.”[70] Separated by millennia, they project two vivid images of the violation of the Celtic ideal of generosity.

Must we conclude at this point that Yeats’s nationalist project was a complete failure. Any such conclusion would need to be subject to one substantial footnote—Easter 1916.

Easter 1916

The unsuccessful rebellion from April 24, 1916 through April 30, 1916 by a group of approximately 1500 to 2000 members of the Irish Republican Brotherhood led by the poet-schoolmaster Padraic Pearse and its aftermath, including the summary execution by the British of 15 of the leaders, has endured as the most potent symbol of the Irish nationalist myth. As one historian, not particularly sympathetic to that development, has observed: “We in Ireland are all in a sense children of the revolution…and for the past sixty years scholars and statesmen alike seem to have been mesmerized by the Easter Rising of 1916.”[71] The event , which also included the issuance of a Proclamation of an Irish Republic signed by Pearse and a number of the other leaders, has attained mythical status despite the actual facts. It was poorly planned and executed, resulted in the destruction of many sections of central Dublin and initially generated anger by the Dublin populace against the participants because of such destruction and what was perceived to be an unwarranted loss of life. In sum, the failed rebellion seemed to be a poor candidate for the most enduring myth of the Irish nation. The role of Yeats is central with respect to the unfolding of the event and the evolution of the myth.

Although Yeats was out of the country during the rising and generally shared with other Dubliners a negative view of the actions of the rebels,[72] his fingerprints were all over the rebellion. Shortly after Yeats’s death, Maud Gonne observed: “Without Yeats there would have been no Literary Revival in Ireland. Without the inspiration of that Revival and the glorification of beauty and heroic virtue, I doubt if there would have been an Easter Week.”[73] The available evidence supports her conclusions and critical to them are the inspirational influences of Cuchulain and Cathleen ni Houlihan upon the rebels.

Pearse was a enthusiastic devotee of Cuchulain’s commitment to self-sacrifice and he had placed at the entrance to his school the notable response of Cuchulain that he would trade a long life for fame. His curriculum was infused with the role of Chuchulain as the model boy hero. In an attempt to fuse Christian and pagan mythology, Pearse frequently cited together Christ and Cuchulain as examples of sacrifice for the common good. The pervasive influence of Cuchulain on Pearse and his followers is reflected in a late poem by Yeats, “The Statues”: “When Pearse summoned C uchulain to his side/ What stalked through the Post Office?” (VP 611)[74]

It is difficult to over-estimate the influence of Cathleen ni Houlihan on the Irish nationalists who filled the ranks of the Easter Rising. After its inaugural production, the play had been produced a number of times subsequently by both the Abbey Theatre and others in Dublin and had most recently appeared at the Abbey on March 11-14, 1916, a month before the events. On the night before his execution, Pearse wrote a poem “The Mother” with lines echoing Cathleen’s words as the mother mourns the death of her two sons dying for “a glorious thing”: “They shall be spoken of among their people,/ The generations shall remember them, And call them blessed.” One of the leaders of the uprising from her prison cell called the play ‘a sort of gospel to us.”[75] In a moment of self-reflection in a later poem, Yeats seemed to acknowledge the relationship between Cathleen and the Rising: “Did that play of mine send out/ Certain men the English shot?”[76]

The influence of Yeats on these events is obviously of significance, but the most notable contribution of Yeats to the creation of the Easter Rising myth lies in his assumption of the role of the ancient Celtic fili in writing about the events. As part of this process, his view towards the rebels changed considerably, prompted in part by his reaction against the British summary executions. A couple of months after the Rising, he noted in an introduction to one of his volumes that “’Romantic Ireland’s dead and gone’ sounds old-fashioned now. It seemed true in 1913, but I did not foresee 1916.”[77] In the wake of the executions, Yeats wrote three poems about the Rising. Two of them express generally unreserved praise of the rebels, but it is the third, “Easter 1916,”[78] which although reflecting some ambivalence has contributed most powerfully to the myth of the Rising.

During the course of the poem’s 80 lines (relatively long by Yeats’s standards), he exhibits three distinct reservations about the leaders and the event. He first observes the ordinariness of the leaders whom he has frequently passed “at close of day” among “grey eighteen-century houses…with a nod of the head or polite meaningless words ,” and who are living a life of “casual comedy.” While he does express personal affection for some of the leaders, he also notes that personally he did not like or was disappointed with others.

His third reservation is reflected in a series of questions about the revolutionaries’ activities. However, each of the questions is followed by a response that tends to diminish the significance of the question. After a long interlude about the unchanging stone in the midst of the “living stream” (lines 41-56), he concludes that “too long a sacrifice/ can make a stone of the heart” and queries “when may it suffice?” He then dismisses the question by assigning the role of judgment to Heaven and reminds us that “our part” is “to murmur name upon name.” With this response, Yeats first gives us a hint of the role that he is assuming in the wake of the tragic events. He is harkening back to the ancient fili tradition of a praise poem on the heroic deeds of others, those who had “limbs that had run wild.” His next question focuses on the political wisdom of the rebellion: “Was it needless death after all?” for it was possible that “England may keep faith” by fulfilling its promise of Home Rule after the conclusion of World War I. Again the probity of the question is diminished by a reflection of the more profound aspects of the events which transcend the practical: “We know their dream; enough / To know they dreamed and are dead.” As we have seen, the dream was always a potent experience for Yeats, a source of creative ideas, an intermediary for communication with the supernatural. In this context, it becomes the symbol for heroic inspiration. The third question returns to the issue of another potential character flaw: “what if excess of love/ bewildered them till they died?” His response ignores the substance of the question and instead proceeds to the fulfillment of the requirements of his role as the poet:

I write it out in a verse—

MacDonagh and MacBride

And Connolly and Pearse

Now and in time to be,

Wherever green is worn,

Are changed, changed utterly:

A terrible beauty is born