When One Sex Attacks The Other, Both Lose

Many feminists describe the history of humanity as a male tyranny, oppressing and maltreating women at every opportunity. Their name for this is the “patriarchy;” a name intended to send a shudder down the spines of all who hear it; the mother of all conspiracy theories.

This doctrine is believed as a matter of faith, its holders brooking no dissent, and divides the world into “true believers” and the damned: “woman, good,” “man, bad.”

Meryl Streep, that model of political correctness, recently proved to be an apostate by stating:

“Sometimes, I think we’re hurt. We hurt our boys by calling something toxic masculinity. I do. And I don’t find [that] putting those two words together . . . because women can be pretty f—ing toxic . . . It’s toxic people. We have our good angles and we have our bad ones. I think the labels are less helpful than what we’re trying to get to, which is a communication,[1] direct, between human beings. We’re all on the boat together. We’ve got to make it work.”[2] This sums up much of the point of this article.

Believers in “patriarchy” look at the existence of successful men as evidence that the system is set up for the benefit of males. Never mind that men make up over 92% of prisoners, die younger, do much worse in the education system, get sent off to die in wars in numbers far exceeding women, are overrepresented among the homeless, and do most of the dirty body-destroying jobs the rest of us do not want to do. Men are represented in greater numbers both at the top and the bottom of various hierarchies.

The notion of “patriarchy” is a subset of “social justice” conspiracy theories that divide the world into oppressors and victims. Success and achievement are evidence that a group belongs among the “oppressors,” in the same way that the first group the Russian communists shot were the “kulaks;” Russian peasants who had done well enough to be able to hire other peasants to work for them. The fact that Asian Americans do the very best as a group educationally and vocationally, despite being a small minority with no particular political power, is a quite uncomfortable fact for the social justice believers. They have no possible way to explain this using their ideas.

One might ask too, where women dominate, e.g., education departments, social work, and nursing, are they too participants in “patriarchy?” If not, why not?

Women are the primary drivers of sexual selection, determining which men get to reproduce, and, strangely enough, they have had a tendency to choose the stronger and more capable of the bunch. Men’s historical contribution of provider/protector gets represented as a conspiracy against women, producing a horrifying Catch-22 for men. If you are a successful man in a leadership position you are an evil tyrant filled with toxic masculinity. If you are a miserable failure, then you are a contemptible wretch. It seems the only good man is a dead man.

Having suggested that a male tyranny characterizes the totality of human existence all that is needed is evidence. Then, in an instance of what is called “confirmation bias,” a selective search is made for unpleasant things ever done to women, not worrying about similarly horrible things perpetrated against men, nice things about men, or nice things men have done for women.

The result is an ugly and repellent account of the way men and women are connected to each other. A necessary part of a response to this is to rehabilitate the image of men – otherwise, why would women want to reconcile with moral monsters?

A list of male contributions in architecture, art, music, literature, philosophy, poetry, theater, medicine, math, biology, chemistry, physics, engineering – the provision of the water coming out of the kitchen tap and showerhead, plumbing, roads, hospitals, the phone in your pocket, you name it, would present a more positive picture of the male input to humanity.

But, thanks to anti-male propaganda, it is possible to read Facebook posts where one woman casually comments to the other that “men suck,” and is met by bigoted bland agreement by a married woman in a way that is entirely socially sanctioned.

Again, men are who built your house, designed, built and installed your heating system and AC, mined the coal and uranium for the power plants driving these systems at great risk to their lives, are responsible for making those power plants and powerlines, mined the metals used in the products you buy, designed and built your cars, radically reduced mortality during childbirth, invented contraception and tampons, collect your garbage, fix the roads, your leaking roof, invented glasses and contact lenses, the stereo you listen to, the TV you watch. The invention of the alphabet, both Latin and Cyrillic, the printing press, the internet and airplanes are pretty handy too. That is pretty good for a class of people all of whom suck.

Most, possibly all, of these contributions are good and beautiful. To object to these lists is to object to the good and the beautiful. Who cares about the sex of those who provided these things? These things should be celebrated. Then why is sex being mentioned? Because of the tendency of some feminists to regard men as a blight upon the planet and the oppressor of women with few, if any, redeeming features. Remarking on the good points of one group of people is not to denigrate another group. Every praise of a woman or women is not a slap in the face of men, and vice versa.

I know one person who indeed behaves in this manner. If someone’s intelligence or good looks, male or female, is praised, she narcissistically regards this as a negative comment concerning her own looks and/or intelligence – making everything about her. To praise Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo, Shakespeare, Bach, Mozart, etc., is not to insult anyone else. And their works should not be rejected based on the race and sex of their makers, although this is indeed happening at many colleges.

For those who claim that the word “patriarchy” is a neutral description of society and in no way any form of criticism of men, then these remarks are not addressed to them. However, as soon as the next step is taken and the “patriarchy” is held to represent the oppression of women, then there is nothing neutral about it!

Resentment, when not directed at an actual specific harm perpetrated against you, and hot showers, and a non-leaking roof are not instances of harm, is a perverse combination of love and hatred to which all human beings are prone. The qualities and achievements of another person or group of people in this case, is loved and admired. You want to possess them. Unfortunately, someone else possesses these good qualities and they are hated for it. That is part of the human condition and it is pathological. The healthy response to such a situation is to aspire to be like the admired person or group of people and to use their achievements as inspiration as to what is possible. Train to be a plumber, roof repairer, airplane designer yourself. Generally plumbing and general contracting are not in fact areas that feminists are particularly clamoring for.

It has been observed that men, unable to give birth to children, find other areas in which to be productive, such as in cultural contributions. Male achievement could then be regarded as compensatory. And, it should not be forgotten, that male achievement is frequently made possible by women’s contribution to home life and child care, with male achievement being related to helping all members of a family. Some women executives have commented that what they need is a wife at home if they are to work sixteen hour days – but most are reluctant to be regarded as a meal ticket for a man; to be the breadwinner. Their leeriness of role reversal should at least give pause for thought.

Anyone who trivializes the beauty, goodness and worthwhileness of giving birth to children and taking the lion share of raising them has not had children, I hope. Cultural and other achievements pale by comparison. We can plausibly imagine that Nick Cave, one of whose sons died while still a teenager, or John Travolta, who had a child die, would give up their fame and fortune in a heartbeat at the prospect of getting his child back. Writing a book does not compare to the meaning that having children introduces into a person’s life.

Warren Farrell comments that feminists tend to focus on the shadow side of men – as the major perpetrators of violent crime, which they are indeed are – while overlooking man as savior, which they also are; the fact that if you are to be cut out of your car after a car accident, to be the recipient of the help of paramedics, or to be physically dragged out of a burning building in a fireman’s lift, it is also most likely to be a man doing that. Unremitting praise of men would be ludicrous, as is relentless criticism and focus on their dark side.

In Jungian terms, there is the Tyrant King and the Good King. There is the Evil Queen and the Good Queen. The notion of the “patriarchal tyranny” makes room for the Tyrant King but omits the Good King. The Good King is wise and just and deserves to rule because he is competent. Men dominate the world of plumbing and aircraft maintenance because they have demonstrated the most competence and interest in those areas. We know from empirical studies that men as a group tend to be more interested in things than women, and women as a group tend to be more interested in people.

We know that tyrannical behavior is a losing proposition in the long run. Dominant male chimpanzees turn out to be excellent at empathy. They are careful to make friendly alliances with other chimps and not to behave unreasonably lest they provoke a desire for revenge. Tyrannical chimps find themselves being ganged up on by lower ranking males and literally torn to pieces, starting with having their genitals bitten off. Tyrannical behavior generates justified resentment in the dominated, and paranoia and fear in the tyrant. Unfortunately, even a position of power generated through hard work and competence can produce unwarranted resentment in the form of envy. This is the kind of resentment to avoid. The fact of male achievement and prominence in positions of responsibility is not evidence of a conspiracy or of tyrannical behavior.

The Evil Queen in this Jungian terminology is the emasculating woman who sees all strong, masculine, competent men as bad. In Snow White the Evil Queen, the shadow queen, “could not endure that anyone should surpass her in beauty.”[3] The mere presence of a man at a top of a hierarchy is equated with power and thus oppression. Competence is removed from the equation. Men are not to strive for competence in case they “oppress” anyone. Thus the only good man is an incompetent, non-threatening, emasculated and thus harmless man. The relative failure of men in high school and college is either seen as a good thing or simply not a problem. The Good Queen is compassionate and wants everyone, regardless of sex, to achieve their very best.

There is also the bad mother who figuratively devours her children instead of granting them their freedom and helping them become independent; who guilt trips them into doing what she wants. The good mother is the one dying soldiers cry out to on battlefields as they lie in pain.

It might be possible to go so far as to say that no woman wants to be judged by her sex and to have her options limited by stereotypes. And neither should she be. What is true as a generality, of a group, is not necessarily true of an individual.

Generalities are useful in explaining different outcomes between groups. If women are complaining about discrimination against them as a group, contending that the relative dearth of women in STEM, for instance, is due to sexism, then groups are the topic.

As just mentioned, men tend to prefer things, women to prefer people. Thus it should be expected that there be a predominance of men in certain occupations like engineering, contracting, plumbing, surgeons, mechanics and for women to tend be the majority in psychology, social work, teaching, and nursing. This is in fact the case. Large numbers of women in engineering would then indicate that women’s preferences are being ignored, as is the case in Iran and India where 50% of engineers are women.

Of course, that does not mean that the relatively few women who are interested in engineering should be prevented or discouraged from following their interests. It certainly would not indicate that women engineers should be expected to be inferior to male engineers – just as male psychologists or nurses should not be expected to be any worse than women.

When it comes to moral judgments no one should be judged by his group membership where the group is determined by immutable characteristics like sex. This can be contrasted with choosing to join the Nazi or Communist parties.

Morally, no one should be despised due to race, sex, or ethnic origin. All people should be judged, if at all, by their achievements and the quality of their own actions.

Recently, the actor Liam Neeson commented that quite some time ago a female friend of his was raped by a black man. In a state of moral derangement he claims that he walked down the street with a baseball bat looking for the first black man who gave him an excuse to beat him up. Holding one person morally responsible for the actions of someone else in this manner makes no sense. One black man should not be punished for the crimes of another. The idea of “group blame” is morally unintelligible. What is true of black men is true of men and women in general.

Even if “men” (an abstraction) had been oppressing “women,” (another abstraction), no individual man is responsible for this. Hating one particular man, or all men, for what some men might have done, is evil and irrational. Holding one man or all men responsible for what some other men might have done is no more rational or moral than Neeson’s racist derangement: intent on punishing an innocent black man for the crime of another black man.

Morality requires that the individual Person be regarded as sacred and of infinite worth; as made in the image of God with an immortal soul and thus connected to Divinity.[4] All other considerations are to be subordinated to the intrinsic value of every single Person regardless of sex, race, or any other characteristic. While unequal in all human characteristics such as abilities and interests, each Person constitutes a world or universe of his own and must be cherished equally.

The characteristic of an ideology is that it places some other value above the Person. Examples include feminism, nationalism, humanity as a group, the social good, communism, fascism, social justice, utilitarianism, equality, progress, happiness, science and well-being. All ideologies are sacrificial cults that promise to exterminate and scapegoat as many victims as it sees fit in the name of the “cause.” Stalin murdered party members as readily as actual ideological opponents. Under the sway of ideology, the Person is nothing; the imaginary greater good is all. Ideologies are evil because they reduce the Person to a nullity – an expendable nothing of no intrinsic worth whatsoever, to be sacrificed to the cause at any moment. No man or woman is safe when confronted with an ideology, including the ideology’s most arch proponents.

To announce one’s devotion to regarding the individual concrete Person alone as of infinite worth; to be protected against the bloodthirsty demands of the mob in all circumstances, is to abandon all ideologies. Groups have no real existence; just concrete individuals. The group is an abstraction. To categorize someone as a member of a group and then to anathematize that group is to obliterate the Person from view. Dehumanization is the precursor to the gas chamber. The scapegoated represent something to the mob; pure evil, the face of patriarchy, the oppressor. What the scapegoated is actually is a Person whose Personhood is about to be ignored by the mob that joins together in shared hatred and relishes that hatred; revels in it. The temporary bond that results is like a diabolical parody of love and meets the same need for connection that most people feel.

Stoning is the perfect mob method of immolating the victim because all participate in the murder. Jesus’ response to a mob intent on stoning an adulterous woman? “Let him who is without sin cast the first stone.”

Ideologies have no time for facts and truth and are in fact hostile to any facts that contradict their aims. Scapegoating requires that the innocence of the victim be ignored. Only the truth that witches do not exist and that they did not cause social turmoil could have prevented the Salem witch trials. Evil requires lies.

Ideologies are valued as a means to an end by their adherents, e.g., the supposed betterment of women as a group. However, extrinsic values are dependent on intrinsic values. A means to a worthless end has no value. If women as a group is the end with intrinsic worth, any individual woman can and should be sacrificed anytime it is decided to be in the interest of the group. But concrete individual women are the only kind of women who actually exist and the only kind of women who can be benefited. Actual concrete Persons are sacrificed in the name of an abstraction with no feelings, and no real existence – the group.

Without the truth of the infinite intrinsic worth of each Person, regardless of sex and race, there is nihilism. Any woman or man at any time is fair game to be murdered, doxed and ostracized whenever convenient without this truth. Feminists, for instance, can and do at times anathematize feminine women who “conform to gender stereotypes,” thereby hindering “the cause.”

Truer and More Beautiful Descriptions of How Men and Women are Related to Each Other

Feminism can often seem like the jaded cynicism of a divorced woman in her fifties who wants nothing more to do with men. Or the same divorced woman’s inability to say anything nice to her children about their father; a bitter, one-sided and inaccurate character assassination. This is the last thing a loving parent should want to inflict on their children; or a teacher on her students.

The meme of “patriarchy” is one, recent, ideologically driven account. It characterizes the sexes as at war with each other. The Bible, in Genesis, has a far more benign origin story:

But for Adam no suitable helper was found. 21 So the Lord God caused the man to fall into a deep sleep; and while he was sleeping, he took one of the man’s ribs and then closed up the place with flesh. 22 Then the Lord God made a woman from the rib he had taken out of the man, and he brought her to the man.

23 The man said,

“This is now bone of my bones

and flesh of my flesh;

she shall be called ‘woman,’

for she was taken out of man.”

24 That is why a man leaves his father and mother and is united to his wife, and they become one flesh.[5]

Woman was to be a helper and companion for man, not a slave and object of maltreatment. Since man and wife are to be of one flesh, such a malignant relationship would be quite masochistic.

A myth depicts truths that cannot be expressed in prosaic or syllogistic form. The story element makes it more accessible than philosophy. Stories show; philosophy theorizes. Myth can more easily address the emotional side of the human condition than theory since theory is restricted to rational analysis. And “patriarchy” is a theory and interpretation used to beat men over the head.

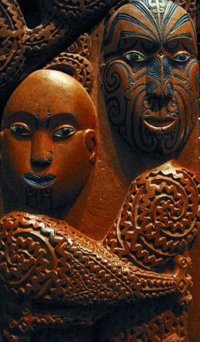

The feminist “patriarchy” story is a glum slander on men and a mischaracterization of the nature of the relation between the sexes. A better alternative would be the Maori creation myth – something similar to which can be found throughout world cultures. In it reality as we know it is created by the separation of Mother Earth and Father Sky. In the story, rain is the tears Father Sky cries due to his longing for his beloved, which is really rather touching and even beautiful.

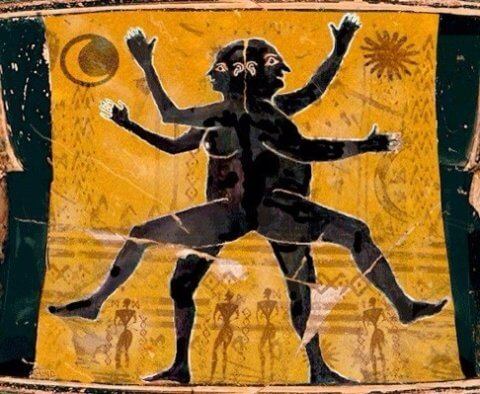

In Plato’s Symposium, Plato has his character Aristophanes, named after the famous comedic playwright, tell a myth explaining the nature of romantic love. In the myth human beings started off as globular beings with two faces and four arms and legs. The faces were on either side of their spherical heads pointing in opposite directions. These early people were so mighty and hubristic that they challenged the gods. Zeus, in punishment and perhaps a little fear, cut the humans in two. The two halves found this so traumatic that they clung to each other, trying to merge into one, until they would drop dead from thirst and hunger. Zeus, taking pity on them, invented sex so that the two halves could unite in a temporary ecstasy and then part for a while before coming together once again.

Romantic love is thus characterized as a desire for unity and being made whole. There is a dependence on another person and a longing to be with them. This is a much truer and more beautiful description of the actual relationship between men and women than invocations of “patriarchy.” Reducing male/female relations to a competitive power struggle is taking a single tiny element and representing it as the whole; the defining characteristic of ideology.

Women hold sway over men with sexual allure and the promise of companionship, the blessings of children, and domesticity. Femininity can add a touch of delicacy and softness to the rough journey of life where men are often in competition with each other partly to win affection and admiration from women.

Both men and women are interesting mixtures of masculine and feminine tendencies that can fit together like a jigsaw puzzle.

In reality, each sex fascinates the other and represents something of a mystery to the other. And often they make up for each other’s deficiencies; for instance, women often play the major role in a couple maintaining an active social life.

In the distant past, men and women had to cooperate in the interests of mutual survival. Competition between men and women was simply not feasible. Male foragers and hunters between the ages of 25 and 45 were the only ones generating more calories than they consumed and then shared the food they got with women of all ages, the children they were looking after, and younger and older men.[6] If men were relentlessly self-serving and selfish humanity would have died out before we ever got beyond the hunter-gatherer stage.

In the recent past, within my father’s living memory (b. 1928), wash day took all day. Kerosene heaters were put under a large tub to boil the clothes for two hours, the clothes were then put in bluing liquid added to the water to make the whites whiter, rung through a wringer, put on a clothes line to dry, then ironed. Each iron was heated on a wood-burning stove and replaced with the next one once it got cold. To make breakfast it was necessary to chop wood, start a fire in the stove and wait an hour until it got hot enough before cooking could begin. There was no contraception and so a wife could have a myriad of children while doing all this, with not much chance of an education and no work outside the home. While the wife did all this, it was the man’s job to earn a living as best he could.

Such factors meant that a division of labor between men and women was necessary. It was not a matter of one sex violently suppressing the other.

It’s All About Power, Right?

Power is an element in all human relationships, for instance, between parents and children. If power and the abuse of power starts to predominate in this relationship, something has gone horribly wrong. The parent/child relationship should be primarily one of care, concern, love, and minimal supervision; shaping and socializing the young child, teaching him self-restraint, discipline and respect for others. Tyrannical parents exist, unfortunately, but this represents a pathological exception, not the norm.

Post-modernism has a tendency to emphasize power above all else. This is partly the result of rejecting the notion of objective truth and there being a supposedly infinite number of interpretations possible with no way to select between them. This turns things into a fight for dominance rather than a search for the truth. This perverse truth-rejecting view has combined with modern feminism at times to focus on power for political propagandistic purposes. Russian communists in the 1920s argued that the “cause” should take precedence over truth. But this view is self-contradictory. Is it true that the cause should take precedence over truth? If this is not true, then the cause should be subordinate to truth. If it is true, and the truth is to be followed, then it is also not true that the cause should eclipse truth.

So, it is a mistake to focus too much on the balance of power between the sexes because it runs the risk of characterizing the lives of men and women throughout history as a power struggle and then producing a competition to see who has had it tougher. Something similar can happen when it is pointed out that the number one consideration for men, regarding the choice of a romantic partner, is female beauty and the most salient consideration for women choosing men is the man’s social status and income. Men compete with each other, generating hierarchies of competence, and women then select from among the winners, typically choosing men of equal or higher status than themselves (hypergamy). Though these are important truths of which everyone should be aware, they obscure the bonds of love and dependence that actually connect the sexes.

But, if we are focusing on power, women exert sexual power among other things. Acting like a jerk and expressing contempt for women is going to be counterproductive to winning the favor of women. When TV shows present 1960s advertising industry men, for instance, as behaving like boors towards women this is sometimes thought to represent reality as though it were a documentary. In reality, such men are likely to remain childless losers. Social status and employment might be the most important consideration, but it is not the only one. Similarly, female beauty might be the number one drawcard, but if a woman has a nasty personality, a sense of self-preservation will minimize the chance of a marriage proposal.

All it will take is a high social status man to act like a gentleman towards women for him to be more successful in sexual selection by women.

Love involves respect, admiration and trust. Contempt is more hurtful, repulsive and counterproductive than anger. Any man or woman who has any choice in the matter, with any whit of common sense and with a minimum of self-destructive impulse, will not consciously choose a jerk to marry.

It is the male losers in the game of sexual selection who might tend towards bitterness, and this will just further exacerbate their chances of being rejected. Much of feminism exhibits a similar bitterness from the other side – but it is a preemptive anger, encouraging cynicism and a focus on power before romantic experiences have even begun for the individual woman.

When in groups of only men, or only women, occasionally the sexes will poke fun at the opposite sex; finding their own perspectives and emphases to seem more “natural” and understandable. A kind of “Men! (Women!) What are you going to do?” This kind of good-natured ribbing is consistent with the two sexes behaving in a sociable and friendly manner when in mixed company, with a degree of humoring the proclivities of either sex.

Countering the “Victim” Narrative

Because gender relations are typically only presented from an ideologically distorted and female perspective, it is necessary to present an alternative view, otherwise the list of unanswered questions and unrebutted assertions is likely to predominate in someone’s mind. Many people will never have encountered any alternative to the woman as victim idea. There is the risk that in offering an alternative narrative, and thus introducing choice into the equation, what will result is a game of victim-claiming one-upmanship. This is a game that for biological and cultural reasons, women will almost necessarily win. Thus the reader is asked to bracket his or her agonistic (competitive) tendencies and to try see things from another perspective – a perspective intended to reduce, not encourage, a sense of outrage.

To begin, recourse to myth is again necessary. In Genesis, again, Adam and Eve eat from the tree of knowledge. The knowledge they gain is of good and evil. This marks the transition from an animal existence and moral innocence, to the human. What follows describes a key part of the human condition.

“I will greatly increase your pangs in childbearing;

in pain you shall bring forth children,

yet your desire shall be for your husband,

and he shall rule over you.”

The giant brains and thus heads of humans mean that contractions for women are much more severe and painful than for other creatures. The idea of the husband ruling over his wife can be explained after reading what God had in store for men:

“Cursed is the ground because of you;

through painful toil you will eat food from it

all the days of your life.

It will produce thorns and thistles for you,

and you will eat the plants of the field.

By the sweat of your brow

you will eat your food

until you return to the ground,

since from it you were taken;

for dust you are

and to dust you will return.”[7]

One thing is immediately obvious – neither sex has it easy. Historically, men and women have worked together in a shared effort for survival with marriage centering around the well-being of children. The image of a cigar-smoking man sitting around lording it over women as any kind of norm is not supported by the facts.

It is possible to read long interactions between feminists about gender relations where children are never mentioned, and yet it is childcare and biological evolution that has contributed the lion’s share to dimorphism, and male and female roles. The extreme helplessness of human children, the fact of pregnancy, and how long it takes for children to become independent are crucially salient to this discussion.

Sex role divisions in human beings resemble penguins where one parent (the father) looks after the eggs and chicks, while the mother fishes. Or, more closely, owls, where the mother looks after the babies while the father hunts and keeps up a constant supply of food.

Camille Paglia notes “women have rarely worked side by side with men in the way they now do in the modern workplace, whose competitive operational systems were devised by men for maximum productivity. Despite their general affluence, professional women of the Western world have been chronically unhappy for decades,[8] and I conjecture that it is partly because they have been led to expect happiness from a mechanical work environment that doesn’t make men happy either.”[9]

Most work is not idyllic or particularly fulfilling. Most men will be subordinate to some other man. The number of men at the top of any competence hierarchy will be, by its very nature, tiny.

With agriculture, described in the Genesis passage, men become the primary providers of food as they were in hunter/gatherer societies. Childcare responsibilities will also have contributed to women’s economic dependence on men. With the exigencies of necessity, the question of whether this is a good or bad thing does not really come into it.

Thanks to agriculture, men leave the home to work in the public realm. Women’s energy is focused more on the private realm. With the man gone for much of the day, women will tend to rule at home and to socialize with other women. Men will tend to associate with men outside the home. Camille Paglia comments, “the sexes throughout human history actually had very little to do with each other. There was the world of men and the world of women, each with its own spheres of influence and activity. Women didn’t take men that seriously, and vice versa.”[10]

Women’s economic dependence on men is the result of a necessary division of labor. It might give men a slight edge in terms of certain kinds of decision-making – hence the “ruling over” comment. However, since for a man a wife is the main source of love and affection in his life, he is emotionally and sexually dependent on her, on her taking care of the children, cooking and weaving. And of course, all people, man or woman, emerge from the womb of woman and are nursed by her as babies.

Thus, the sexes are mutually dependent. The practice of gift-giving from husband to wife can be seen in multiple cultures as payback for affection. A loving husband wants to curry the favor of his wife.

Having the role of provider has often meant that men have been responsible for property and economic transactions in public life. Thus a house or car might in the past have been in the husband’s name. He would more usually be the one signing the contract and negotiating the price. This has changed in tandem with women entering more into public life.

Modern American women typically have more sources of moral and emotional support than men, tending to retain closer relationships with other adult women and with their family of origin than men. This, coupled with the fact that when a woman leaves, she also often takes the children with her, means that divorced men, losing all their sources of love and affection are 8.3 times more likely to kill themselves than women.[11] In this regard, men are the weaker, more vulnerable sex.

Women have the lion’s share of sexual selection and they tend to gravitate to those men who are successful in a hierarchy of money, status and social prestige. Power, it is said, is the great aphrodisiac. This is something well-known to celebrities. Currently, this fact is presented as a nefarious abuse of power – but it is a power that is derived from the attraction such men hold for women. A very beautiful woman or a socially prominent man might choose to exploit their appeal to the opposite sex for mercenary purposes and in both cases it can be unsavory.

When the power a man has is the ability to offer a role in a movie to an actress the whole thing becomes a seedy, ugly business; turning sex into a quid pro quo instead of having anything to do with love.

A woman might be economically dependent on a man if she is a stay-at-home mom, but a man will be emotionally dependent on his wife. Acting in a tyrannical manner will generate an angry resentful wife. Living with someone who hates you is no fun at all. If a man wants things to go well for himself, he also wants a happy wife – hence the phrase “happy wife, happy life.” Belittling comments and expressions of contempt can and do come from either sex and both are toxic for a relationship. Any failure to perform the male role well, to maintain employment, to get a promotion, or some other failure to achieve, can draw sarcastic comments from a wife. And an underperforming man can be regarded as a wife as just another child she has to look after.

It is not in a man’s interest to throw his weight around. In fact, women have more spending power than men, suggesting that most men are generous and freely share their earnings. The extreme can be seen in Japan where traditionally women are given the man’s pay check and then give him an allowance.[12]

Prior to agriculture was horticulture: making holes in the ground, inserting a seed and then covering it up – maybe with some rotten fish as fertilizer. Men and women could do this equally well and the resulting power dynamic was 50/50. These societies are called “matriarchal,” but really political power was shared equally. In the case of the Iroquois, male chiefs were selected by the women, slanting power in women’s favor.

Sometimes these pre-agricultural societies are eulogized, but they also engaged in human sacrifice, in many cases with baby girls viewed as the most valuable offering. Since horticulture is so much less efficient than agriculture, returning to that period would also mean significantly compromising food production.

By the time Genesis was written, agriculture was the dominant form of farming. The physical strength advantage that men have over women is relevant to agriculture and the oxen-powered plowing of fields.[13] Agriculture, pregnancy and childcare do not mix well. A division of labor between the sexes in this context simply made the most sense. Historically, a lot of work outside the home will have been hard scrabble. In fact, in the US, first class slaves worked in the home as “house slaves,” and second class slaves in the fields as “field slaves.”[14] Dirty jobs involving hard physical labor and exposure to danger are still a largely male domain – deep sea fishing, coal-mining, or working on an oil rig would be great examples.

Marriage was invented by most cultures and the main beneficiaries of marriage are children, not men. Occasionally, non-monogamous marriage arrangements have existed. In that case, the Middle Eastern Sultan or Chinese emperor had to be wealthy enough to provide for and protect all his wives and children.

Both sexes have sacrificed personal pleasure and preferences for the benefit of the next generation of both boys and girls, and men in particular have sacrificed their lives in war. This has a basis in biology. Males are more expendable than females when it comes to maintaining a population. One man can impregnate several women if necessary, but a woman cannot have multiple pregnancies at the same time. Thus, it is easier to recover from male decimation than female.

Of course, women used to frequently die in childbirth, but this was not the result of any human decisions. Sending men off to die in battle has an element of human agency missing from childbirth – hence the horror of the Spartan mother who told her son to come back victorious or on his shield, i.e. dead. Maternal feelings of protectiveness of offspring are eclipsed by the necessities of communal survival.

Coming to value the individual at all, man or woman, is arguably a fairly recent Western cultural development. In the context of a community, e.g., a tribe, just trying to survive against threats from other human communities and from the possibility of starvation, child mortality, plagues, floods, drought, pestilence, what is good for the group is regarded as paramount and individuals will be killed in human sacrifice or sent off to die in battle as a matter of course. Individual preferences about exactly how someone wants to live will be given short shrift in such a context.

Valuing children is really about group survival. Failing to maintain population size is terminal. Again, it is not about the well-being of any one person and certainly not of any one sex.

There have been a few prison/surveillance cultures for women – much of Ancient Greece was, and many modern Middle Eastern countries continue to exclude women from being able to casually participate in social life outside the home without male chaperones. It is hard to say how much this is driven by an excessive desire to protect and how much it is straight up fear of female promiscuity. Men, but not women, always have the danger that they may end up raising someone else’s progeny – making female adultery of greater significance than male. Like many other elements of life such behaviors have largely been eliminated in the West at least, and life has improved in many respects for both sexes.

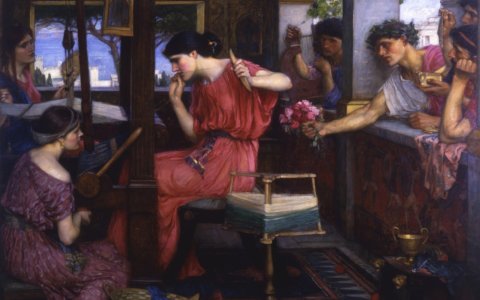

Regarding Ancient Greece, restrictions on freedom of movement can be contrasted with the attitude towards women in the Greek tragedies and myth which is generally very impressive. Goddesses are powerful and effective figures. Hecuba, wife of Priam, Penelope, the wife of Odysseus, Iphigenia, Electra, Clytemnestra, Pentheus’ mother Agave, Medea, and more, are also thoughtful, well-developed, with the full range of human characteristics, with admirable qualities and capable of vengeful resentment. The Greeks knew not to underestimate the intelligence and capacity for vindictiveness of women.

One thing that has not changed is the male-only duty to fight in wars. All Ancient Greek men were expected to fight as soldiers when needed, which was often. Today, American men, but not women, must sign up for selective service (the draft) with very onerous punishments for failing to do so. Men can face five years in prison or a 250,000 dollar fine, though rarely enforced. More concretely, those who fail to sign up are ineligible for financial aid, federal grants and loans, certain government benefits, eligibility for most federal employment, and eligibility for citizenship if the man is an immigrant. Most states make registration a condition of getting a driver’s license or ID card, state-funded higher education benefits and state government jobs.

The greater value given to women’s lives continues. Even today, despite communal survival not really being in question anymore in Western countries, in the US, two male construction workers die every day on the job, down from 38 a day in 1970.[15] Male coal miners die of black lung disease from coal dust inhalation around the world and the US has one million volunteer fire fighters, 96% male,[16] who risk their lives to protect complete strangers. Many of these men are destined to die young thanks to inhaling smoke from the burning of modern building materials like PVC piping. Football players are expected to demonstrate their manliness by disregarding personal wellbeing and suffer repeated concussions with disastrous effect – oftentimes leading to mental illness (depression) and suicide. At the very least, trauma to their bodies will generate arthritis for many. There are no equivalent female statistics.

The Department of Health and Human Services has ten regional offices for women’s health, and none for men. The US Department of Agriculture has a Women, Infants, and Children Program. If fathers cannot provide more money than the government, the government takes over and the father is excluded. The US Dept. of Justice has an Office on Violence Against Women – though domestic abuse is 50/50. Only one shelter out of thousands will admit men and there are no shelters just for men. There is the National Institutes of Health’s Office of Research on Women’s Health, Center for Disease Control and Prevention’s Office of Women’s Health, Food and Drug Administration’s Office of Women’s Health, Health Resources and Services Administration’s Office of Women’s Health. There are no male equivalents.[17]

The chivalrous “women and children first” idea can seem a bit bleak from a male point of view too.

In The Myth of Male Power from which many of these points are taken or inspired by, Warren Farrell points out that things that are true about black men are also often true of men in general. Men are twenty times more likely to be incarcerated than women, 2.4 times more likely to be among the unsheltered homeless,[18] to die younger, not to attend college, not to graduate from college, to suffer from heart disease and hypertension, to expose themselves to the repeated head and body trauma of boxing and other contact sports.[19]

When Warren Farrell is invited to speak on college campuses these days he gets protested as a purveyor of “hate speech.” Apparently, hate speech is anything that differs from the feminist account of patriarchy – the fact that the “hate speech” is crammed full of facts for which evidence is provided is not considered pertinent; an instance of the “cause” being considered more important than truth.

To continue, men are far more likely to be the subjects of medical experiments. An unintended side-effect of more commonly treating men as guinea pigs is that the effect of medicines on women is less well-known. It is common these days to claim that not doing as many drug tests on women reflects sexism against women![20] Part of the concern appears to be the possible consequences of drug experiments on women who may be pregnant – again, not a conspiracy by men to neglect women’s health. Half to those vulnerable fetuses will be female.

Men traditionally defer to women; standing when a woman enters the room, pulling out her chair for her to sit in, giving up his seat for her, letting her through a door first, helping her on with her coat, and serving her first at meal times. These are the same behaviors expected of slaves.[21] These are signs of deference.

If there were something wonderful about being male, adult men would not commit suicide at three and half times the rate of women,[22] they would not die seven years younger than women,[23] they would not always be the majority of victims of violent crime in the US (the 1990s were the apogee with men being three times more likely to be victimized) and men would not earn the most while spending the least. Department stores and shopping malls devote perhaps seven times the amount of space to items for women versus for men. Women are the only “oppressed” group as likely as the “oppressors” to be born into a wealthy and privileged family.[24]

Women cast more than 50% of the vote.[25] There are more male politicians, but women have more of a say in who gets elected. Men earn more, women spend more. In both cases, who has more power?

Despite suicide being a much greater risk for men than women, when the National Association of Social Workers studies suicide, they study only female suicide. In fact, the funding for suicide research only allows the study of girls.[26] The director of the American Association of Suicidology has said that he would love to find out why boys killed themselves but he too can get no funding for it.

The Affordable Care Act offers Well-Woman Visit for students (possibly all women). A counselor offers birth control advice and how best to avoid STDs, and takes an entire health history. If, for instance, a grandparent suffered from depression and breast cancer, the student is given information about breast cancer genetic tests (BRCA tests) and the latest research on mammography screenings. She will get comprehensive screening every year and pap smears, all of it for free. There is no such thing as a Well-Man Visit, no family history, no comprehensive family history, no screenings. “The Affordable Care Act provides all these provisions for women, and none of those provisions for men. And all of those provisions for women are free.”[27] By engaging in gender discrimination the ACA violates its own law.

The US Department of Justice has web links and PDFs for violence against women,[28] but there is no such thing for violence against men. The Google search engine is skewed to favor searches for harm against women, but not against men. Together, this is a clear indication of which sex we actually care about in this regard. Thirty-two pages of references for studies, with brief descriptions, are included at the end of this article showing that men and women are about equally likely to be the victims of domestic abuse. It is estimated that more men than women are raped every year due to men being raped in prisons and elsewhere. About 279,758 men are raped or sexually assaulted in prisons and jails,[29] while 120,000 women[30] are subjects of rape or attempted rape outside prison. If this number of women prisoners were being raped there would be an outcry.[31] There is no reason to think that this impacts men emotionally any less than it does women. Since it violates sex role expectations, the humiliation and loss of dignity might be even worse for men. However, it is still regarded as acceptable to joke about this.

Of the fictional portrayals of people being killed in movies, about 95% are men.[32] Try imagining it being the other way around and what would be said about that.

So, no, patriarchal society has not been set up for the sole benefit of men and the oppression of women.

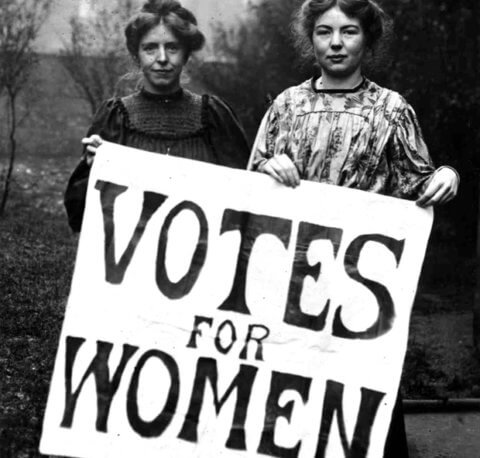

Is the Fact that Women Got the Vote Later than Some Men Evidence of Oppression?

Voting in the US began by mirroring the male/female division of roles; women bearing primary responsibility for home life and the private realm, and men for the public sphere. At the time, agriculture was still the main driver of the economy.

The first presidential election was in 1789 when George Washington was elected. The ability to register to vote was dependent in many states on proof of payment of a poll tax: thus on property and wealth. Poor white men were ineligible to vote. What followed historically was a tendency towards gradually extending suffrage, with women gaining the vote in 1920 thanks to the Nineteenth Amendment before many black, Native American and poorer white men. Women asked and men responded positively. Many men who fought in WWI (1914-1918) were ineligible to vote.

The 1848 Seneca Falls Convention in New York is traditionally held as the start of the women’s rights movement. Suffrage was not the focus of the convention. A push for women’s suffrage became more prominent after the Civil War. Areas like Wyoming, Utah and Washington granted women voting rights prior to 1920.

If someone were to be angry that the vote was not extended sooner to women, what should be the response? Sorry?

It was the British who decided to end the international slave-trade at the cost of money, lives and effort. This occurred in the 19th century. Should we be angry at the British for not leaping into action sooner, or be happy that they took it on themselves to make this breakthrough? Maybe, in both cases, the reaction should be “Yay!”

The Behavior of Some Feminists is Consistent with Some Journalists’ Fears about Women’s Suffrage

Prior to women’s suffrage, some worried that women were too emotional, irrational, had a tendency to personalize disputes and were unable to separate themselves from the topic debated and thus could not be counted on to make decisions in an objective, unbiased manner or to make a healthy contribution to public debate.

Women should ensure that none of these worries come true. One consideration is the notion that women are especially empathic and often have a motherly concern for anyone who might be regarded as a victim. The downside of empathy is complete ferocity against the supposed perpetrators. A mother bear empathizes with her cub and will literally tear a threat to them to pieces in as gruesome an act of violence as can be imagined. Rules of evidence and calm consideration of facts and consequences must prevail over such “motherliness” or the innocent will suffer.

Janice Fiamengo in a Rubin Report podcast commented that some of these early concerns seem to be borne out by some modern feminists, by some recent changes on college campuses, and aspects of the MeToo movement.

Some feminists have claimed the scientific method and requirement of objectivity are evil – exemplifying patriarchal (i.e., male) tendencies – sometimes called “phallologocentrism.” Such comments are deeply irrational and even anti-rational.[33] Following this train of thought, some Canadian universities have instituted “Indigenous Science” to be infused throughout the science curriculum.[34] This will draw upon a post-modern notion of “narratives,” and “discourses,” rather than truth. How is the legitimacy of “Indigenous Science” to be evaluated if not via normal science? When objective standards are used, then there is no “indigenous” or “nonindigenous” science; just “science.”

The introduction of “Indigenous Science” seems part and parcel of the concern for “victims” and thus an expression of motherliness.

Many college campuses have instituted policies where a male student or professor accused of a sexual misbehavior cannot cross-examine his accuser, cannot hire a lawyer, and can be expelled/fired.[35] Even the exact nature of his supposed crime and who is accuser is, is not necessary made known to him. This violation of due process is defended on the grounds that the student does not go to prison if convicted. He merely has his education ended, his life disrupted, his reputation ruined, and his chances of future employment impaired. Such accusations are put on a student’s record.

It is common for MeToo proponents to say that women who make accusations should be believed and that women do not lie about such matters. Examples of women lying about such things abound. Reasons include trying to explain to a parent, husband or boyfriend where you were all night. How you ended up pregnant though your husband has been away at sea or in the army when the baby was conceived. Revenge for a lover not calling and thus feeling ashamed and used. Regret at your own possibly drunken behavior and wanting to push the blame onto someone else. Sometimes divorce lawyers recommend making an accusation as a tool for leverage to gain property or custody of the children. The fact that women are almost never prosecuted for false accusations is very important. It means there are no consequences for lying. In China, if a woman is found to have made false accusations against a man she is sentenced to the length of time the man would have served if he had been convicted. “One [American] woman accused her newspaper delivery man of raping her at gunpoint when she needed an excuse to be late to work.” She had already made the same false accusation with no consequences. The second time she receive counselling.[36] Another reason for false accusations is mental illness. This would seem like an instance.[37]

A U.S. Air Force study found that 60% of all rape allegations were false.[38] High rates of dishonesty in nonmilitary contexts were also found when the lead investigator checked. When The Washington Post got counties to open their files, two of the biggest counties had recorded accusations to be false or unfounded 30% (Prince George, Maryland) in one case and 40% (Fairfax, Virginia) in another.[39]

In the Air Force study, many accusers withdrew their accusations and admitted they were lying when they learned they would be subjected to a lie detector test. Importantly, the determination that they were lying was not the result of administering the test – a test which can be unreliable and whose results are not generally admissible in court. The women confessed just at the prospect of such a test.

The idea that women never feel a desire for revenge or invent excuses unfortunately does not happen to be true.

The case of Tawana Brawley is one of the more notorious instances of a woman making a false accusation. A fifteen year old, she had not come home for four days and was found in a dumpster covered in feces with racial epithets written in charcoal on her body. She accused four white men, including a police officer and a prosecuting attorney, of having raped and attacked her. Her case became a cause célèbre with Al Sharpton and others publicizing the events. Thousands marched in rallies supporting her.

No part of her story was true. It now seems that she was scared of her rather strict father’s possible response to her staying out all night with her boyfriend and she concocted the story to get herself off the hook. She never intended that her made up excuse become a national scandal.

When it turned out she had lied, Al Sharpton and others said the truth did not matter – that “it was the principle” that counted.

Some MeToo proponents have similarly claimed that if a few innocent men are wrongfully smeared and their lives ruined that this is the price to be paid for taking women’s claims of sexual harassment, etc., seriously. The truth must be secondary to the cause.

Ignoring truth is a prerequisite for scapegoating.

Western civilization over two thousand years has slowly and painfully refined how evidence is presented in court and what kind of evidence there can be – determining that if the price for avoiding wrongful conviction is that some guilty people go free for lack of evidence, then this is worth it. Rumors are not admitted as evidence because anyone can start a false rumor. The accused must be able to face his accuser and the accuser must be able to be cross-examined. “Hearsay” which is “I heard Bob say that Susan did it” is not admissible. If that is true, we need to hear directly from Bob and cross-examine him too. Was he perhaps joking, lying, was it the same Susan, was he actually in a position to hear Susan, etc? Then we want to hear from Susan.

Most important is the presumption of innocence. It is generally not possible to prove innocence. An individual cannot prove that he has never killed or raped anyone. It cannot be done. Thus, it is absolutely crucial that the burden of proof always be placed on the person making a controversial claim – in this case, that a man has committed a sex-related crime. Evidence for the claim must then be presented and the accused have the opportunity to try to poke holes in this evidence. This is a matter of straight logic. Misplacing the burden of proof in an argument is an error absolutely fatal to the pursuit of truth and, in this case, justice.

Carol Gilligan claims in A Different Voice, a book embraced by many feminists, that men tend to favor the impartial application of the same rules to everyone while women tend to feel sorry for the “losers” and want to make an exception.

The motherly desire to protect the vulnerable that many women feel can get combined with utter brutality and a disregard for truth and logic. While men too can be irrational, it is not men for the most part who have questioned the value of objectivity, due process, innocence until proven guilty or science. However, men have proven themselves willing to go along with these things to stay in the good graces of women and to play savior.

Second Wave Feminism – the Rise of Misandry, Scapegoating Men and Male Self-Hatred

“Misandry,” is the hatred of men; an esoteric term compared to the much more prevalent “misogyny.” At this point, in many contexts, not embracing misandry is to be morally suspect.

Second wave feminism arising in the 1960s sought to help women gain access to work outside the home. Male legislators immediately rushed to pass laws to facilitate this such as the Civil Rights Act of 1964 outlawing discrimination on the basis of sex, among other things. The Equal Pay Act of 1963 amended the Fair Labor Standards Act aimed at abolishing wage disparity on the basis of sex.

Betty Friedan, a prominent feminist, was enthusiastic about women entering the work force. However, she had some major caveats about how women ought to go about doing this. Friedan figured that if women wanted access to jobs traditionally done by men, they ought to emphasize that women are capable of exhibiting characteristics more traditionally associated with men and with doing jobs well. These would include such things as being strong, capable, competent, self-reliant and so on. Friedan was emphatic, that under no circumstances should women claim to be victims. Victimhood implies weakness, subjugation, inability to look after oneself, and the need to be saved and protected. None of that seemed compatible with being chosen for employment, especially in more traditionally male occupations, nor with the likelihood of gaining respect for a job well done. However, scapegoating men proved just too tempting and effective.

Women’s studies departments – as with most other “studies” departments – could not exist without the scapegoating of men.

In scapegoating, the mob bonds together in shared hatred of the victim(s). In total denial of reality, the mob claims to be victimized by the person or group of people the mob is actually victimizing. So, for instance, a lynch mob claims that a single individual is terrorizing the populace, putting say, white women, in danger of predation and generally sowing disorder and causing people to fear for their safety. The mob pretends to need saving from the perpetrator who is in fact the victim of the mob. The mob then lynches the victim considering itself to be the victim defending itself from the miscreant.

The scapegoating of men by women has a peculiarly evil dimension to it. Men are particularly prone to becoming willing accomplices in their own demonization thanks to their traditional biologically-derived role as the protector and provider for women. If women claim that they need protecting from men, many a confused male will incongruently try his best to save them; hoping all along to gain the love of women.

Men who have renounced hopes for personal well-being are called “heroes.” Self-hating men can hope to raise themselves in the eyes of women and they do not even need to die on the battlefield or rescue someone from a car wreck, or burning building, to do so.

Metaphorically, the man will engage in self-flagellation, beating his back with iron-hook laden leather strips and then want to show women his damaged back asking “is this good enough?”

Scapegoat victims are prone to believing the accusations against them anyway. Given the human tendency to conformity derived from mimesis, the propensity to imitate other people, if the mob comes to share a negative view of a victim, the victim may well come to agree with them. This is particularly likely if the victim is offered no moral support by anyone else.

Plus, since the male role is to devote his life to women and children, sacrificing his life if necessary, if men claim to be the innocent victim of scapegoating this flies in the face of what is considered manly and both men and women are disgusted by unmanly men. A man who needs to be saved is contemptible and anyway, who is going to save him? It is not the female role to save men.

Since men fulfill the male role partly to deserve the love, affection and admiration of women and the respect of other men, any attempt by men to protect themselves from scapegoating from women will produce all sorts of paradoxes and double-binds. Contempt from both sexes can be expected. For this reason, a male equivalent of a feminist movement is likely to remain a tiny niche phenomenon. The current tactic is to call men’s groups “hate” groups. All that is required to qualify is to challenge any element of feminist orthodoxy.

When women complain they are “a damsel in distress” and both men and women respond positively. 1980s feminists claimed to be disgusted by this dynamic and some of them rewrote fairy tales to depict women saving themselves. However, contradictorily, the 1980s feminists went right on demonizing men and claiming to be victims.

Feminists are likely to claim that biology is not destiny. Just because women give birth to babies and have the breasts to feed them, it does not mean that that should necessarily be women’s sole role in life. And yet, in pleading for male help, feminists have historically drawn from this biological well and continue to do so.

So women claimed to be victims in the 1960s. Men rushed to help by, for instance, passing laws as already mentioned, trying to be heroes and saviors. The twist of course was that this time the people men were trying to protect women from were men. Victims must have oppressors. There can be only one candidate – the other half of the human race.

This means women hate men and men hate men. Male self-hatred is a very real phenomenon – often it is driven by failing to live up to the male role e.g., by being unemployed. But it can also be the result of well-intentioned men trying to help women.

Men were scapegoated as the cause of women’s problems even though all that was happening was that women were calling for a change in their traditional sex role, a role there for the sake of children, and men rushed to help them. What was socially acceptable for women quickly changed. However, the male sex role has continued unabated; meaning lots of options for women, one acceptable option for men; being the breadwinner.

Women are free to work full-time, part-time or not all. They can look after children full-time, part-time or not at all. The male role has changed not at all – provide. For maximal respect and to be regarded as a desirable mate, work full-time or nothing. Unemployed but handsome men are not considered highly desirable husbands by most women, while being a beautiful but unemployed woman is no handicap at all to being viewed as marriage material. The dictates of biology remain just what they were in this regard.

Sometimes the relative dearth of female scientific and other cultural achievement is presented as evidence of oppression. Male intelligence has a wider dispersion than female. While the average intelligence of men and women is the same, there are more male geniuses and male sufferers of mental retardation and violent offenders. Just one of the top one hundred chess players in the world is a woman. Given this fact, there will never be the same number of supremely gifted women scientists, writers, painters, philosophers, etc., as men. But neither will there ever be as many female violent criminals or mentally challenged individuals. Resentment at the prominence of men at the top of many areas of achievement is misplaced. To a large degree, men competing in these hierarchical arenas are indirectly just trying to please women anyway. Being hugely successful as a woman often does nothing much for her desirableness as a mate.

The female chess champion in the above statistic claims that she views chess merely as a hobby and that she could be even better if she took it seriously. This indicates that her self-worth is not particularly tied up with achievement. Men are much more likely to be obsessive and hypercompetitive with their self-worth highly linked to their social status determined by their place in an achievement-based hierarchy – whether that is poetry-writing, or motocross. A reasonable expectation would be that the men in that top 100 list of chess players take the game deadly seriously, devoting oodles of time and effort to maintaining or improving their ranking.

Living with someone who hates you is no fun, so many a husband will try to play along to keep his wife happy, ironically, vocally confirming that men deserve to be hated, in order to be hated less! And then, if a man was not yet married, he would be eager to curry favor with women by adopting their perspective and whatever point of view they seemed to respond well to. So many men became willing contributors to their own scapegoating to the point that individual white men can be heard denouncing their own existence and blaming themselves for all that is wrong with the world. The fact that logically this position requires their own immediate suicide does not quite seem to dawn on them. It becomes an instance of so-called “virtue signaling.” An aspect of this behavior is that no actual sacrifice is required – just to mouth certain fashionable tropes.

The more the man wants to be the savior of women (think firemen and policemen), the traditional role, the more he has to hate everything he stands for including “paternalism,” the desire to protect women! Thus arise sexual harassment laws concerning “hostile working environments” aimed at protecting women, while men such as coal miners and construction workers literally die on the job with few such protections and little protest.

Arguably, this has resulted in a society in which many men have colluded in identifying the oppressor as themselves.

Warren Farrell points out that both sexes have a light and a dark side. Men are both rapists and murderers, and benevolent fathers and saviors. If someone needs rescuing from a burning building, or the nation needs defending from hostile enemies, it is most likely to be a man who is risking his life to save anonymous strangers. But this savior aspect of men has in recent decades tended to be ignored and hidden by such gender neutral language as “fire fighters” and “police officers” despite these professions being 97% to 98% male-dominated.

The dark side of women includes being the majority of child murderers. Their role in the sexual abuse of children is also glossed over. In anonymous telephone surveys when people are asked if they consider themselves to have been sexually abused as children, half of the abusers are women abusing boys. Women also make up half of the perpetrators of domestic abuse, using weapons and the prohibition on men hitting women to make up for their smaller size and strength.

In the 1980s “all men are rapists” was a popular refrain for a while. The phrase was uttered by a character in a novel by Marilyn French who commented that it was not her own sentiment and was never intended as a statement of reality. But what was until recently the nadir for men occurred in the 1990s with the scare about male pedophiles. Being male somehow became associated with pedophilia. The hysteria was so intense that it has changed most English-speaking cultures dramatically to the extent that children can no longer walk to school or play outdoors unsupervised. Or, if they do, the parents are likely to be regarded as irresponsible. This cultural change was not brought about by any actual changes in the risk of child abduction, murder and rape, only by a generalized fear of men. Air New Zealand and Qantas have a policy that no unaccompanied child can be seated next to a man.

Likewise, suspicion towards men was also evidenced in the 1990s by the fashion for psychiatrists convincing their female patients that their fathers had sexually abused them. Women would present with symptoms such as general anxiety and depression, and would be told that it was because of repressed memories of being abused by their fathers. Among other things, this had to do with Freudian psychology momentarily becoming popular again. It is known now that when people suffer from traumatic events, they do not typically repress them, instead, they cannot stop thinking about them. Most, possibly all, Vietnam War veterans suffering from PTSD do not repress their memories, they have nightmares about them and cannot get the memories out of their heads. Many fathers were wrongly demonized and grandfathers were often deprived of contact with their grandchildren until the time came when many women realized they had been duped by their well-meaning, but misguided, psychiatrists. Women have written books detailing the misery they have caused and the male lives ruined.

Male self-hatred is a cancer for men. In demonizing men, masculinity itself came under fire, as did traditionally masculine virtues with bad consequences for all. The new nadir for men is the phrase “toxic masculinity” – an idea that many colleges are teaching as though it were fact.[40] Aimed at men who repress emotion in order to be manly (think surgeons, soldiers, athletes, fire fighters, first responders, paramedics), in fact the type of men most likely to play a savior role for women, no healthy version of masculinity is lionized. The implication is that “masculine” = “bad.”

This has arguably led to a culture in which the balance between masculine and feminine sensibility has shifted hugely in favor of the feminine; a kind of cultural withdrawal of masculinity. One of the most famous examples of this kind of thing is the “no child left behind” notion. This may sound good to some ears as an expression of compassion, but to an educator it is bizarre. The only way to achieve something like that would be to lower standards to such a degree that even the most hopeless case can “pass.” This, in fact, is the tendency. Things like grade inflation, getting higher and higher grades for the same mediocre work, seem to be over-determined, probably having an economic component too, but there is definitely a feel-good “compassionate,” no hurt feelings aspect to it too.

Certainly something bad has happened to male achievement in educational contexts. Boys are being out-performed by girls at all levels of education.[41] This seems to be a combination of factors like the withdrawal of male teachers from the scene, particularly at the elementary level, apparently in response to the pedophilia scare and a change from high-stakes testing which tends to suit boys more, to low-stakes assessment requiring the constant handing in of work and thus consistent organizational abilities which tend to favor girls. In the past in New Zealand, girls tended to do better at primary school and the boys started to get serious during high school and to take home the school prizes as they prepared for their roles as bread winners, but no longer. Many women continue to be interested in marrying high-earning men, so they can work part-time while raising children and this desire is getting harder and harder to fulfill. This may be contributing to low birth rates there and elsewhere.

We know that married couples produce much better outcomes for their children. If masculinity really were toxic, single-mothers could be expected to have much happier, healthier children. This is not the case. Boys and girls suffer, but the absence of fathers affects boys much more than girls. 85% of violent offenders are fatherless. Educational and vocational performance is much worse for fatherless boys. Drug and alcohol abuse is higher among the fatherless as is the likelihood of ending up in prison.

Academic and vocational performance by race in the US is at its peak with Asians, then Jews, then Non-Jewish whites, Hispanics, Native Americans, then blacks. This corresponds to the racial distribution of married, two parent households. Only 2 in 10 Asians are born out of wedlock, 3 in 10 whites, 5 in 10 Hispanics, 6.6 in 10 Native Americans, and 7.7 in 10 blacks.[42]

Egalitarianism – we are all equal – is also rampant and is a more typically feminine notion. It denotes the kind of love that requires nothing in return. It is unconditional. No one is better than anyone else. All little sheep are loved equally. No one is to be left out in the cold. Unconditional love is a good and beautiful thing, but in practice, it needs to be leavened by conditional love which can be earned. It is earned by achievement, getting better, developing and by being pushed and encouraged in a more traditionally masculine manner. Rather than raising self-esteem through self-esteem classes, self-esteem is raised by doing things or gaining skills of which one can be proud.

Egalitarianism proponents can also end up claiming that men and women are equal because they are the same. This leads to the contradiction that men and women are said to be so similar that any deviation from women being 50% of any traditionally male occupation is unfair, while also claiming that women are so different from men that having women on a job will contribute to a vital viewpoint diversity. Contradictions must be absolutely anathematized. Once even one is permitted rationality is over. Absolutely anything, including false things, can be “proven” if it is regarded as permissible to contradict yourself.

Egalitarianism also does not happen to be true. If almost any human characteristic is named, on person will be better or worse than another individual in that regard. There is equality before the law, as an ideal, and one person, one vote. This is legal and political equality in principle. Each person may also be equal as God’s creatures, as John Locke suggested. But, typically, egalitarianism is extended to criticizing or being uncomfortable with any demonstration or even suggestion of superiority. Hence, it is greatly attractive to the resentful.

Ironically, given the name, the logic of militant feminism has often ended up demonizing being feminine too. Women who choose to stay home and raise children are sometimes seen as sell outs and as failing to help the cause of women. Wearing dresses, putting on makeup, the painting of nails, and in any way conforming to traditional gender roles tends to be seen as bad. So in the end, the desire of some women in the 1960s and since, to make use of the damsel in distress trope to help the cause of women, has ended up demonizing men, generating a cultural and ideational vacuum filled by feminine values at great social and cultural cost, and, like the snake that eats its tail, even tending to produce a hatred of all that’s feminine.

Since feminists still want occupational success for women, they continue to push women to adopt more traditionally masculine tendencies to promote success in the workplace. However, in order to promote their cause, feminists continue to demonize men and to make use of victim power. This also is an inherent contradiction.

Since modern feminism cannot survive without an oppressor/victim dynamic, men and masculinity continue to be vilified and presented as the cause of all women’s problems. The only good man is a man who is like a woman – feminine, and the only good woman has to be more like a man, which is insane since men and masculinity are considered “toxic.”

Since women are likely to be more feminine than men, and both femininity and masculinity are bad, women are likely to end up being self-hating like men. They are likely to feel that it is men who are causing the problem rather than feminist ideology. In fact, female happiness has declined since the 1960s as self-reported by women and this dynamic could well be part of it. Women and men are simply left with nowhere to turn.

Appendix A

References Examining Assaults by Women on their Spouses or Male Partners: An Annotated Bibliography

Martin S. Fiebert

Department of Psychology

California State University, Long Beach

Last updated: January 2007

SUMMARY: This bibliography examines 196 scholarly investigations: 53 empirical studies and 43 reviews and/or analyses, which demonstrate that women are as physically aggressive, or more aggressive, than men in their relationships with their spouses or male partners. The aggregate sample size in the reviewed studies exceeds 177,100.

Aizenman, M., & Kelley, G. (1988). The incidence of violence and acquaintance rape in dating relationships among college men and women. Journal of College Student Development, 29, 305-311. (A sample of actively dating college students <204 women and 140 men> responded to a survey examining courtship violence. Authors report that there were no significant differences between the sexes in self reported perpetration of physical abuse.)