William H.F. Altman, The Bogotá Lectures; §1. “Plato and Aristotle”

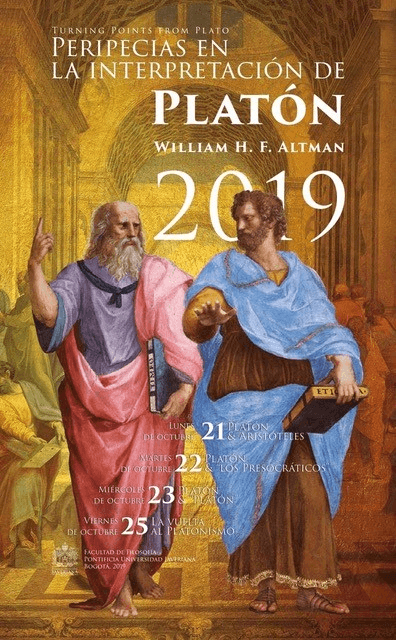

Walking toward us from the center of Raphael’s School of Athens are the two giants of Ancient Philosophy: Plato and Aristotle. By depicting Plato as an old man, Raphael preserves the fact the younger Aristotle was his student. But the two are twins all the same: joined in conversation, and each carrying a representative book with one hand while making a symbolically significant gesture with the other. Aristotle’s gesture expresses what we would now call his “empiricism,” and in any case indicates the tangible and visible source of his many contributions to natural philosophy. Plato’s gesture, meanwhile, is a perfect expression of his Platonism: he points up and out, toward the unseen. Plato’s Platonism occupies the center of these lectures, and those modern or ultra-modern philosophers and scholars who today would deny that Plato himself was a Platonist will therefore come to play an important role in them. But imagine if this question were reversed, and instead of being encouraged to state your opinion as to whether Plato was a Platonist, you could only win a valuable prize on a televised quiz show by correctly identifying “the philosopher who separated a supra-natural realm of unchanging Being from the ever-moving flux of what ‘is’ merely Becoming.” In those circumstances, not even those who are most insistent in denying that Plato was a Platonist would fail to answer correctly, for what other answer could they give? Everybody knows what “Platonism” is; I will be exploring how Plato has recently come to be something other than its creator.

Raphael’s painting illustrates how this began to come about. As appropriate as I believe Plato’s gesture to be, the book he is carrying tells a different story, especially in comparison with the one in Aristotle’s hand. Aristotle’s Ethics is concerned with the proper conduct of human life; Plato’s Timaeus explains how the cosmos came into being. These literary choices raise another question likewise at the center of these lectures: was Plato a Socratic? This question explains why I will be discussing “the Presocratics” tomorrow night. The point is a simple one. Seconding Xenophon and Plato—whose claims are then brilliantly illustrated by Cicero’s word-image about Socrates calling philosophy down from the heavens and into the lives of men—Aristotle tells us that Socrates was in no way with concerned with physics, cosmology, and natural science, but devoted his attention exclusively to the proper conduct of human life.[1] By placing his Ethics in Aristotle’s hand and Timaeus in Plato’s, Raphael would seem to be suggesting that it was Aristotle, not Plato, who was the true Socratic. I regard this this as exactly the reverse of the true state of things. It is as if Raphael depicted the two giants of Ancient Philosophy to illustrate the possibility of the left hand not knowing what the right hand was doing, for unless Plato is pointing toward nothing beyond the visible heavens, the choice of Timaeus threatens to contradict his other-worldly gesture. And this contradiction runs deeper. In a painting that makes the difference between Plato and Aristotle the basis for assigning the various philosophers to one side of “the School of Athens” or the other, Raphael appropriately placed on Plato’s side both Xenophon and Socrates himself.

Others have explored the intellectual background of Raphael’s painting,[2] and I would like to emphasize two points that have emerged from those explorations. The first is that we are looking at a synchronic history of Ancient Philosophy, one that importantly depends on the rediscovery and Latin translation of Diogenes Laertius’s The Lives of Eminent Philosophers.[3] The second is that the intellectuals who influenced the reception of that text, and who thus influenced the detailed commission Julius II gave to Raphael, were committed in principle to the harmony of Plato and Aristotle.[4] Not only are the two philosophers depicted conversing amicably but their dialogue is replicated in the balanced symmetry of the picture as a whole. The painting makes and was intended to make a point about the trans-historical interplay of seemingly opposite doctrines: they take place, as it were, under one roof. It also points to a principle that unifies the thought of these two “great princes” of philosophy: Aristotle is bringing down to earth the same insights that Plato had considered only in their disembodied form.[5] As a whole, then, Raphael’s School of Athens is a static representation of a harmonious and synthetic unification of a diversity that in fact unfolded through disputes in historical time. It is the abolition of the chronological element that allows the picture to harmonize the disparate views of Aristotle and Plato, and to symbolize their synthesis, as it were, at the point of friendly intersection between Aristotle’s Ethics and Plato’s Timaeus.

Raphael’s School of Athens was painted at a time when the most important history of Ancient Philosophy had been written centuries earlier. But in the centuries that followed, written records of ancient events unfolding in time would proliferate and ramify. In Plato’s case, he would not only be situated as a historical phenomenon between his predecessors and his followers—and thus between Socrates and Aristotle in particular—but he too would eventually become something less than static and more than unitary himself. Beginning in the nineteenth century, Plato would become so historicized that it was no longer sufficient to integrate him into the history of Ancient Philosophy as a unitary phenomenon who had come to be at a certain time but rather to understand how “Plato himself,” thanks to the differences between his dialogues, constituted a variety of disparate phenomena that needed to be integrated under the umbrella of change, evolution, and development. Beginning with an early period when he remained under the spell or influence of Socrates, Plato had developed into the founder of Platonism in his “middle period” before evolving as an older man into a philosopher at once more practical, more analytical, and more cosmological. As a result, the left hand of Raphael’s Plato was harmonized with his right, and the synthetic vision that had made the School of Athens possible was temporalized into an account of “Plato’s Development” as by no means the least important part of “the History of Ancient Philosophy.”

The crucial point, then, is that this history offered a plausible account of how Plato, the erstwhile Socratic, could became a cosmologist in the end. Since this transformation is at the center of these lectures, it is important to be absolutely clear. The ancient testimony was unanimous on Socrates’ indifference to cosmological speculation; he turned his attention away from physics and natural science toward ethics. Meanwhile, the evidence that Plato was a Socratic was undeniable: a character named “Socrates” dominated his dialogues, and from only two of which was this unforgettable and enigmatic character absent. Although present in the dialogue Timaeus, it is Timaeus, not Socrates, who describes how the cosmos comes into being. In the process of constructing this discourse, Plato would allow Timaeus to demonstrate an encyclopedic familiarity with previous developments in astronomy, physics, and cosmology while making brilliant and original contributions and modifications of his own. I regard the fact that it is Timaeus, not Socrates, who creates what has been called “Plato’s Cosmology”[6] as evidence that the degree of harmonization between Plato the Socratic and Plato the cosmologist has been overstated. It is therefore rather the alleged transformation from Plato the Socratic into the author of Timaeus that I will be discussing tonight.

Aristotle is the subject of this first lecture because he was the first to utter the fatal words: “as Plato says in the Timaeus.”[7] In the course of creating what was in effect the first history of Ancient Philosophy, Aristotle integrated Plato into that history not merely as a non-cosmological Socratic but more insistently and in greater detail as the philosopher who had expressed his own views on physics and cosmology—the domain that Socrates had abandoned—not only in his Timaeus but also elsewhere, as we will see. In that history, Aristotle naturally occupied the final and consummating role, and while separating Plato from Socrates in important ways that went far beyond the question of cosmology, he found a way to demonstrate and validate his superiority to both of his great predecessors. Before considering briefly how he did so—how he not only established himself among the greatest of philosophers but in effect crowned himself as their king—it is necessary to emphasize that although he played Socrates off against Plato and Plato off against Socrates to achieve this astounding result, he never criticized Socrates for abandoning cosmology nor praised Plato for allegedly restoring it in a way that would allow Aristotle himself to consummate and complete this restoration. All of this was merely implied.

What Aristotle did do, and did so explicitly, was to separate Socrates from Plato on the ontological separation that forms the basis for Plato’s Theory of Forms: “Socrates gave impulse to this theory, as we said before, by means of his definitions, but he did not separate them from the particulars; and in this he thought rightly, in not separating them.”[8] Despite the fact that Plato’s Socrates does separate them, the important result from Aristotle’s perspective is that his Socrates joins Aristotle himself in rejecting the most characteristic and salient aspect of Platonism. And Aristotle will further combine forces with Socrates by depicting his predecessor as taking the first steps toward the syllogism, the full development of which constituted perhaps the most salient and characteristic aspect of Aristotelianism. But Aristotle uses Plato to demonstrate the errors of Socrates in much the same way that he used Socrates to illuminate the errors of Plato: Socrates had incorrectly believed that Virtue was Knowledge and therefore that incontinence—knowing the right thing to do but being too weak to do it—was impossible. Basing himself on what Plato’s Socrates says about the three parts of the soul and the four virtues in the fourth book of Plato’s Republic, Aristotle could now take Plato’s side against Socrates. And just as he did to Socrates on the syllogism, he did to Plato on incontinence: although his predecessors had taken important steps on the matters on which they were right, Aristotle had surpassed both of them in both. And of course he had surpassed them even more where the two of them had been wrong.

Although Aristotle’s history of Ancient Philosophy has proved to be very influential—to the great detriment of Plato as I hope to show—the post-Aristotle versions of that history have been even more detrimental, especially when it comes to the specific question of “Plato’s Development.” In other words, even though later historiographers have recognized the special pleading, self-aggrandizement, and historical inaccuracies that mar Aristotle’s account of his predecessors, Aristotelianism has exercised a curious effect on the way apparently more critical and self-conscious historians of Ancient Philosophy have subsequently treated Plato. What I mean here by “curious” must be clearly understood, for it is the first example of a “curiosity” that will become a recurrent theme of these lectures. So here it is: although Aristotle himself attacked Plato for separating the Ideas—and that means for being a Platonist—the current image of Plato is based on the notion that Plato developed beyond the doctrinaire Platonism of his “middle period” and curiously became more practical, more analytical, and more cosmological as he became older. In a word, then, the curious thing is that our modern version of Plato tends to become an Aristotelian, and I call that result “curious” because apart from his description of Plato’s Laws, relative to his Republic, as “the later-written Laws,”[9] Aristotle’s ongoing criticism of Plato contradicts the views of later scholars who imagine Plato’s Development along these lines.

And it is not only that the traditional three-part periodization of Plato’s Development has tended to isolate and relativize as “outgrown” the great dialogues of his “middle period,” including Republic, Symposium and Phaedo. Although Aristotle knows next to nothing about this periodization, two aspects of his testimony are crucial not only for the isolation of “middle period” Platonism—and allow me to emphasize the important point that Aristotle never suggests that Plato himself outgrew it—but for creating the basis for two ongoing modern attempts to annihilate it. After briefly noting that the attempt to annihilate Plato’s Platonism entirely is an even more curious phenomenon than the already curious attempt to Aristotelianize “the late Plato,” the two kinds of testimony that I have in mind relate to Aristotle’s account of Socrates on the one hand and to Aristotle’s claims about what the Tübingen School calls “the Prinzipienlehre” on the other.[10] With respect to the latter, Aristotle describes Plato as having modified the two opposed principles of the Pythagoreans, preserving the One “but positing a dyad and constructing the infinite out of great and small, instead of treating the Infinite as one.” He promptly adds that this “is peculiar to him; and so is his view that the numbers exist apart from sensible things.”[11] Although one could speak for hours about the One and Indefinite Dyad—a pairing of principles that Plato never describes or names as such in any of his dialogues[12]—the important point is that Aristotle attributed to Plato a system of principles that not only assimilated Plato inseparably to the earlier history of cosmology (and to the Pythagoreans in particular) but which proved that in this crucial sense, he was not a Socratic.

It is therefore ironic that the Anglophone analogue of German concern with the Prinzipienlehre should be Aristotle’s testimony about Socrates. Linking today’s Anglo-American reception of Plato to the Continent is the center of Plato’s ontological universe: the Idea of the Good vividly and unforgettably described as outside the Cave in the seventh book of Plato’s Republic. On the continent, the scholars of Tübingen have used Aristotle’s testimony to prove that Plato regarded the Idea of the Good as the One, and since without the benign, unifying, and form-giving influence of the One, we would have nothing other than the dyadic indefiniteness of “the great and the small,” its constitutive and immanent role in the creation of a unified cosmos—and thus of cosmology itself—is obvious. Meanwhile, the sharpest minds among the Anglophone proponents of “the philosophy of Socrates” have used the testimony of Plato’s own “early” dialogues to show that Plato, even in his Republic, regarded the Idea of the Good as Happiness, and therefore that he was just as much a eudaemonist as Aristotle unquestionably was.[13] What binds these two approaches into a unity is their parallel attempt to render the most ostentatiously transcendent entity in Plato’s thought, the Idea of the Good, as somehow immanent, whether in physics or ethics. It is as if Plato’s index finger in Raphael’s painting—the perfect pictorial expression of his Platonism—is being annulled by English speakers by reading Aristotle’s Ethics into Plato’s Republic, while continental scholars are widening even further the distance between that finger and Plato’s Timaeus by making Plato, and not only his character Timaeus, into a Pythagorean.

But let’s not miss the forest for the trees. The real connection between these two approaches is Aristotle. For the paired principles of Tübingen’s Prinzipienlehre Aristotle is our principal, primary, and indispensible source; without his testimony, no one could set about finding either it or the necessarily unwritten traces of it in Plato’s actual writings. Scholars may differ, then, on the extent to which what Aristotle calls Plato’s “unwritten teaching” is actually unwritten, but not that regardless of whether it is or it isn’t, it could be neither without Aristotle. And no less dependent on Aristotle is the claim advanced by the most radical followers of Gregory Vlastos that the Idea of the Good is Happiness, and that the same Socrates who never separated the Forms likewise knew that nobody would ever fail to maximize their own Happiness by doing what was bad or harmful to themselves willingly if Virtue was the kind of Knowledge that aimed exclusively the Good. The fact that Aristotle defends his own eudaemonist position in the same book—the first book of his Nicomachean Ethics, the text he is carrying in Raphael’s picture—in which he attacks Plato for positing instead of Happiness the Idea of Good as “the highest good” is yet another example of the same kind of “curious” phenomenon I have already mentioned, and I will be returning to this curiosity in a few moments.

Bedeviling every attempt to give a systematic and analytic account of “the philosophy of Socrates” is not only the inescapable fact that Socrates himself wrote nothing and that the accounts of him that have come down to us—and those of Plato, Xenophon, Aristophanes, and Aristotle in particular—are by no means consistent with each other or indeed entirely consistent even with themselves. A nice why of considering the inadequacy of Aristotle’s early attempt to systematize and define Socrates is that any systematic account must somehow harmonize Aristotle’s insistence that Socrates regarded Virtue as Knowledge with the clash that arises between the persuasive attempts of Xenophon and Plato in particular to depict him as the exemplar of all the virtues while at the same time allowing him to insist—and in this insistence, Plato takes the lead—that he knows nothing.[14] How then can Socrates be virtuous, as we can all see that he is, while steadfastly maintaining his own ignorance if—as Aristotle unquestionably insists[15]—he regarded the virtues as knowledge and indeed denied to possibility of incontinence on that basis?

In Aristotle’s case, indeed, the problem is even deeper and more intractable. For Aristotle, the history of philosophy becomes a catalogue of teachings, opinions, or δόγματα; after all, even if they are unwritten, it is to Plato’s ἄγραφα δόγματα that Aristotle refers, and he duly supplies the appropriate δόγματα for a long line of philosophers beginning with Thales. This approach must break down when Aristotle comes to Socrates, and it is therefore no accident that the only time he mentions Socratic Ignorance,[16] he is not describing Socrates’ δόγματα, as of course he does in other places. As already demonstrated, Aristotle’s Socrates holds both positive and negative δόγματα. On the negative side, he denies the possibility of incontinence and the separation of the Forms, the latter denial a neat piece of legerdemain since Aristotle makes his position seem to be the opposite of Plato’s, which simple chronology—quite apart from what Plato’s Socrates says and does—indicates they could not possibly be. On the positive side, we run into a similar problem: following what Plato’s Socrates repeatedly does in the so-called “early” or “Socratic” dialogues, Aristotle’s Socrates relentlessly pursues the definition of the virtues, and it is this pursuit that will lay the foundations for Aristotle’s own revolutionary syllogistic method.

But by insisting that Socrates regarded the virtues as one and all species of knowledge—and note, please, that the positive δόγμα Aristotle attributes to Socrates is one that Aristotle himself holds to be both misguided and wrong—the inconclusive searches depicted by Plato attain in his history the level of Socratic δόγματα in the end. This is a crucial point. Plato, who repeatedly emphasizes Socratic Ignorance, never states apodictically what his Socrates holds to be true about any of the virtues, not even that “Virtue is Knowledge.” Indeed the dialogue form, where Socrates and not Plato must tell us what Socrates says in any given circumstance—and of course these circumstances are famously varied—precludes the possibility that Plato can do what Aristotle does: tell us about Socrates’ δόγματα whether positive or negative. We can reconstruct “the philosophy of Socrates” in such a way as to uphold Socratic doctrines like the Unity of Virtue, Virtue as Knowledge, and the Socratic Paradox that nobody does or rather makes bad things voluntarily, and we can find texts in Plato’s dialogues to justify such a reconstruction, but we could not do it without Aristotle. And this is true not simply because Aristotle lends credibility to such a reconstruction by his account of Socrates’ δόγματα but more importantly because it was Aristotle who created the kind of Socrates for whom such matters could become δόγματα in the first place. Even in the case of Xenophon’s Socrates, Xenophon is far more insistent that Socrates always aimed to benefit his associates—and therefore adapted his discourses to their individual needs—than that his own Memoribilia should be read as a systematic collection of Socrates’ δόγματα.

But if Vlastos’s version of Socrates—which systematically denied any and all credibility to Xenophon—was importantly dependent on Aristotle’s,[17] Aristotle’s Socrates was drawn most directly from Plato’s puzzling Protagoras,[18] a vividly described boxing-match of words replete with humor, spectacle, and sophistry, and not all of the latter emanating from the sophists themselves. Plato’s Protagoras contains the lengthiest passage defending the Socratic Paradox in the dialogues,[19] and Plato placed that passage in the midst of Socrates’ notoriously tendentious exegesis of a poem by Simonides. The Simonides-exegesis also contains the embryo of the Socratic δόγμα that Virtue is Knowledge,[20] and the dialogue as a whole shows Socrates attempting—by fair means and foul—to prove the Unity of Virtue. With respect to the three δόγματα most commonly associated with “the historical Socrates,” only Meno is as comprehensive as Protagoras, and neither dialogue makes an ironclad case for either the truth of these “doctrines” or for the truth of the related claim that Socrates himself accepted any of them as demonstrably true. In fact, when Meno is forced to admit that not even a scoundrel like him would ever harm himself willingly[21]—for Xenophon has made it crystal clear he delighted in harming others, and his unsuspecting friends in particular[22]—or when Socrates must begin his proof that virtue, an alleged unity that once again remains ostentatiously undefined, can only be taught if we take as an initial hypothesis that Virtue is Knowledge,[23] it may begin to become clear that Aristotle’s version of Socrates is not only based primarily on only one of Plato’s dialogues but on a remarkably one-sided and humorless reading of it.

The easy thing to forget while looking at Raphael’s beautiful and harmoniously balanced painting is that it was only the Renaissance that had made it possible to make Plato and Aristotle equal in height and equally central with respect to importance, gravity, and philosophical authority. Throughout the Middle Ages, Aristotle had been “the master of those who know” and quite simply “the Philosopher”; Plato’s dialogues as a whole were unknown. One is tempted to say that “the Renaissance changed all that,” but the fact is that Aristotle continued to exercise an unchallenged and largely unmerited hegemony over the reception of Plato. This hegemony extends down to the present day and is by no means confined to the Anglophone tradition that begins with Vlastos and the Tübingen School. A single passage in Aristotle’s Politics is sufficient to prove how extremely primitive and unfeeling was his way of reading Plato,[24] and yet the triadic periodization of Plato’s writings depends crucially on Aristotle’s unfeeling and primitive way of reading Plato’s Protagoras. The amazing thing here is that it was nothing Aristotle said about Plato that led the later tradition to distinguish an “early” or “Socratic” phase of Plato’s Development from the “middle period” Plato of Platonism but rather what Aristotle, primarily on the basis of Protagoras, said about Socrates that did so.

And there is another amazing thing that requires emphasis: Aristotle simultaneously criticized and rejected the version of Socrates he had himself created: virtue was not one thing, none of them were simply kinds of knowledge, and incontinence was not only possible but would receive a fully syllogistic explanation from Aristotle. As a result, Socrates’ great value lay elsewhere, and his most important and valid doctrine was negative: unlike Plato, Socrates did not develop his pursuit of definitions—and note once again the role Plato’s “early” dialogues of definition must play in either process—into a full-blown theory of separate Forms. This is the crucial matter, and it is reflected not in the books that Raphael’s two giants are carrying but in what his Aristotle and Plato are doing with their other hands. Even if the Renaissance intellectuals who influenced Pope Julius II were committed in principle to the harmonious reintegration of the transcendent with the immanent—and it is difficult to imagine that a “vicar of Christ,” Italian Renaissance notwithstanding, would pay good money to promote any other way of depicting their relationship—there is a world of difference between Aristotle’s this-worldly affirmation of what is right before our eyes (on the one hand) and Plato’s heavenward gesture on the other. Transcendence and immanence can be harmonized, but it is by no means clear that this harmonization was Plato’s goal, as it clearly was Aristotle’s.

But so great is Aristotle’s authority that many scholars throughout the ages have taken it to be Plato’s goal as well, and for them no single dialogue is more important than Timaeus. The sign of this way of reading Plato is that it places “the problem of participation” in the dead center of things Platonic, and if Raphael’s preceptors had not instructed him to place Timaeus in Plato’s hands, they would likely have chosen his Parmenides instead. Aristotle’s famous hylomorphism is as good a solution as “the problem of participation” is likely to receive, so the question is this: was Plato primarily concerned with how sensible things participated and were informed by Plato’s Ideas, themselves best understood as paradigms or ideal archetypes, whether these are to be found in the mind of god or elsewhere in Plato’s heaven? If we answer “yes,” as the tradition set in motion by Aristotle’s criticism of Plato would have us believe we must, Plato was not a Socratic, for this question is an essentially cosmological question. On the other hand, if it was Plato’s Socrates, not Aristotle, who solved “the problem of participation,” and that he did so by creating a beautiful discourse that pointed his auditors toward the Idea of Beauty in the Symposium, that related the Idea of the Good to the philosopher’s return to the Cave in Republic, and showed why death in an Athenian prison demonstrated how a true philosopher participates in the Idea of Justice, then Plato remains a Socratic, and our answer to the cosmological question must be “no.”

In claiming that Plato was and remained a Socratic, I am by no means denying that he was also a Platonist. On the contrary, my basic point tonight is that it is Aristotle who is entirely responsible for making many of us think that one cannot be both a Socratic and a Platonist. When Plato wants to announce the separation of the Forms, he entrusts that announcement to his Socrates, and Aristotle’s principal error arose from his attempt to identify the Socrates of Plato’s Protagoras with “the historical Socrates” and the Socrates of Republic book 4 with Plato. Although he would have done better to identify Plato with the Socrates of Republic book seven, it is the zero-sum separation that causes the problem, not least of all because Aristotle never considered the need to distinguish Timaeus from Plato. But I need to emphasize that when it comes to Platonism, Aristotle—who has no doubt whatsoever that Plato is a Platonist—has a far clearer understanding of what that means than those who are now questioning or even denying it. There are three things that Aristotle tells us about Plato that are not only true but constitutively true about Platonism: (1) Plato regarded the Ideas as separate, (2) he did not regard the Idea of the Good as Happiness, and (3) he placed mathematical objects between the Ideas and sensible things.[25] Almost all modern accounts of “the Theory of Ideas,” especially those that reject their transcendence or Plato’s commitment to their existence, discount or ignore Aristotle’s testimony about “the Intermediates,” best understood as intelligible images of sensible things, and thus something other than whatever it is toward which Raphael’s Plato is pointing the way.

It will be noted that the first two of these are sufficient for refuting the most radical proponents of the attempt to extend a separation-denying ontology and a ruthlessly eudaemonist ethics into the sacred precincts of Republic 7. But if Aristotle leaves no doubt that Plato did not equate the Idea of the Good with εὐδαιμονία, he opened the door to Tübingen by laying the foundations for the claim that Plato did equate the Idea of the Good with the One. Moreover, by explicitly claiming that Plato derived what he called “the Ideal Numbers” from the first mixture of the One and the Indefinite Dyad,[26] he muddied his own claim that Plato had also regarded numbers as “intermediate.” Although the interpretive issues are complex, the problem is a simple one: if numbers are merely intermediate, they are not Ideas, as Ideal Numbers must be. Harmonizing the two kinds of number proved to be the engine of much fascinating speculation among later Platonists, but the arithmetic lesson of Republic 7 should have been sufficient to show that Plato regarded numbers as necessarily plural aggregates of indivisible “ones” or monads,[27] and that the very notion of a “unitary plurality” or—to use Aristotle’s phrase—of “uncombinable numbers,”[28] was a contradiction in terms, based as it was on the impossibility that what is Many can at the same time also be One. After all, it is only in English that “the United States of America” take a singular verb, and a good first step in understanding U.S. History is to realize why it was only before our Civil War that a poet could write: “the United States themselves are perhaps the greatest poem.”[29]

Despite the apparent complexities, historical and otherwise, the essential point is simple, like the One that cannot be Many. Cosmology, beginning with Thales, is the attempt to find what “One Thing” that “All Things” are, and if numbers are necessarily plural and “the One” is not a number, then “one” is exactly what “all things” cannot possibly be. The problem, then, is not in finding a more abstract or unifying alternative to “water” in some other physical element like “air” or “fire,” and in relation to the Problem of the One and the Many, the only thing surprising about Socrates’ rejection of cosmology is that he was the first to reject it. On the other hand, the history of thought both before and after Socrates proves again and again the vitality of attempts to construct a cosmos on the basis of two equally balanced, antithetical, but necessarily combinable principles, and the avatars of Yin and Yang will continue to haunt the deepest human minds until the end of time. The great achievement of Aristotle’s hylomorphism was that it made an intelligible Form inseparable from the Matter it informed; the two became one. Moreover, by combining inseparably a unifying Form with otherwise formless and thus radically indistinct Matter, Aristotle’s hylomorphism revealed itself for what it was: a post-Socratic restoration of cosmology that was at the same time the avatar of the Prinzipienlehre that Aristotle had claimed Plato had derived from the Pythagoreans.[30]

As already mentioned, apart from a single remark about “the later-written Laws” and the fact that his account of Socrates can be used to segregate a number of Platonic dialogues—and Protagoras in particular—as “Socratic” or early,” Aristotle says nothing about “Plato’s Progress” from “early” through “middle” to “late.” What he does contribute to the question is an account of the thinkers that influenced Plato, in addition, of course, to Socrates. In Aristotle’s account, the two great influences on Plato are Heraclitus and the Pythagoreans. From Heraclitus, says Aristotle—and I along with many others believe he was right to say it—Plato derived the view “that all sensible things are ever in a state of flux and that there is no knowledge about them.”[31] Note first that this kind of influence would suggest why Plato might well have remained a Socratic with respect to the cosmos: how can physics or natural science possibly be a worthwhile pursuit if there is no knowledge about sensible things? Aristotle rescues Plato for cosmology not only by means of phrases like “as Plato says in Timaeus,” but by making the Pythagoreans the other decisive influence on his intellectual development. As already indicated, Aristotle’s account of Plato’s alleged Prinzipienlehre—the doctrine that even its most passionate partisans must insist remains unwritten in his dialogues—emerges explicitly from its Pythagorean predecessor.

Here if anywhere the tradition has shown a remarkable and praiseworthy independence from Aristotle’s account of Plato. Apart from the scholars of Tübingen, that tradition has followed a far more plausible and indeed text-based approach by making not Heraclitus and the Pythagoreans but rather Heraclitus and Parmenides the philosophers—other than Socrates, that is—who most influenced Plato and who therefore best illustrate what Platonism is. Intimated in Parmenides and Philebus, then made explicit in Cratylus, Heraclitus contributes decisively to what Socrates will call “Becoming.” And in Theaetetus, Socrates will distinguish the proponents of flux, including Heraclitus, from Parmenides, the champion of the unchanging.[32] Since Parmenides was principally concerned with what he or rather the goddess who instructed him called “Being,” and since she repeatedly insists that Being is unmoved and unmoving,[33] it is easy to cognize and then to teach the separation of Being and Becoming—and that means the essence of what my quiz-show thought-experiment suggests that Platonism is and always will be—in relation to the combined influence of Heraclitus and Parmenides. With the spirit of Parmenides presiding over one domain and that of Heraclitus over the other, the sensible realm of Becoming is eternally separated from the transcendent realm of Being. It is therefore in their separation, not in their synthesis that we discover the essence of Platonism.

The fact that Aristotle ignores the influence of Parmenides is the Achilles Heel of his account of Plato. Quite apart from the equally mistaken elevation of the Pythagoreans that makes Parmenides’ eclipse possible is a radical misunderstanding of Parmenides himself, whose δόγματα Aristotle naturally must describe in his History of Philosophy. What Aristotle principally misunderstands is that Parmenides’ poems had two parts, and that the goddess described the longer cosmological part of it as “a deceptive cosmos of words.”[34] It is in the section still called “Truth” that the goddess reveals the Being that never changes; only when she has come to the end of “the argument worthy of belief” does she embark upon the cosmology still known as “Opinion” or “Δόξα.”[35] Aristotle gives no indication that Parmenides’ poem consisted of these two parts, and when he turns for the first time from what we know as “Truth” to “Δόξα,” he actually praises Parmenides for now speaking “on the basis of more attentive consideration” since only now is he “obliged to follow the phenomena.”[36] Compare this to the far more accurate account of Parmenides by Aristotle’s student Theophrastus: “he supposes that according to the truth the whole is one, ungenerated, and spherical in shape, while according to the opinion of the many he accepts, in order to explain genesis [i.e., Becoming], that the principles are two, fire and earth, the one as matter and the other as cause and agent.”[37]

Although a distinct improvement on his teacher in the decisive respect that Parmenides regarded “Opinion” an inferior and deceptive alternative to “Truth,” Theophrastus follows Aristotle in a revealing error: he identifies the two principles that the goddess uses to explain Becoming as “fire and earth.” Before explaining what makes this identification erroneous, it is first necessary to show what makes Theophrastus’ analysis of the twin roles of “matter” on the one hand and “cause and agent” on the other so excellent and insightful. Like the Pythagoreans before him and Aristotle after him—and on Aristotle’s account, Plato as well—Parmenides builds a cosmos out of two equally balanced, antithetical, but necessarily combinable principles. As both Parmenides and Plato realized, this is what cosmologists do, so it is therefore what they too will do while creating their own. The difference is: both Parmenides and Plato recognize the opinion-based inadequacy and merely deceptive appeal of the cosmological enterprise from the start. So here’s the revealing error: in Parmenides’ poem, the two forms around which the goddess constructs he “deceptive cosmos of words” are not fire and earth but rather fire and night.[38] What makes this error so revealing is that fire and earth are the two elements around which Plato’s character Timaeus constructs his “likely story” about the genesis of the cosmos.[39]

Unconsciously, then, Aristotle points to the truth that proves that Plato was a Socratic after all: his error makes Plato’s Timaeus the equivalent of Parmenides’ Δόξα. It is the character Timaeus, not his creator Plato, who is the Pythagorean, and Plato’s decision to follow his Republic with Timaeus indicates that the former is his version of “Truth.” Why wouldn’t it be? In the sixth and seventh books of Plato’s Republic—the crucial part of the dialogue deleted from the summary at the beginning of Timaeus—he enshrines the Idea of the Good at the center of his thought, distinguishes Being and Becoming, and praises mathematics for its pedagogical effectiveness in turning our eyes away from sensible things to the intelligible ones.[40] As if all that were not enough, he joins the most perfect statement of Platonist ontology with the equally perfect expression of Platonic ethics: the dilemma called forth by the Allegory of the Cave. The philosopher will not return to the Cave as Socrates did in order to earn prizes for effectively predicting the succession of shadows on the back wall of the cave,[41] soon enough to reappear as “the Receptacle” in Plato’s Timaeus. It is perfectly true that the astronomer Timaeus begins by sharply distinguishing Being from Becoming,[42] but it will be by the Demiurge’s mixture of these two principles—not Fire and Night, or the One and the Indefinite Dyad—that the World’s Soul will come into being before the Receptacle plays host to its Body. It is in the dark light of these mixtures that Aristotle’s words “as Plato says in the Timaeus” prove to be not only his most destructive contribution to Platonism, but the single most destructive thing anybody has ever said about Plato, now forever enshrined visually in Raphael’s School of Athens. But the Stagirite has usefully forced us to consider the causes of things, and what caused him to say what he did is that unlike Plato, Aristotle was no Socratic.

Notes

[1] The principal source of inspiration for these lectures is André Laks and Glenn W. Most (eds. and trans.), Early Greek Philosophy, nine volumes (Cambridge, MA and London: Harvard University Press, 2016); see “Socrates” in volume 8 (33): D2 (Aristotle), D3 (Xenophon), D4 (Cicero), and D7 (Plato).

[2] See especially Ingrid D. Rowland, “The Intellectual Background of the School of Athens: Tracking Divine Wisdom in the Rome of Julius II” in Marcia Hall (ed.), Raphael’s School of Athens, 131-170 (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1997) and Glenn W. Most, Raffael Die Schule von Athen (Frankfurt am Main: Fischer Taschenbuch, 1999) or Leggere Raffaello: La Scuola di Atene e il suo pre-testo, translated by Daniela La Rosa (Torino: Einaudi, 2001). I am grateful to Professor Most for making this edition available to me.

[3] A second source of inspiration (see n1) is the superb new edition of this well-known work: Pamela Mensch (trans.) and James Miller (ed.), Diogenes Laertius, Lives of the Eminent Philosophers (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018), see especially Ingrid D. Rowland’s essay “Raphael’s Eminent Philosophers: The School of Athens and the Classic Work Almost No One Read” (554-561). For Sean McConnell’s useful and indeed mouthwatering review of this important book, see Bryn Mawr Classical Review, 2019.02.28.

[4] See especially Rowland, “Intellectual Background,” 147.

[5] See the quotation from Egidio of Viterbo in Rowland, “Intellectual Background,” 167n52; also in “Raphael’s Eminent Philosophers” (in Mensch and Miller) on 559-59.

[6] See Francis MacDonald Cornford, Plato’s Cosmology: The Timaeus of Plato (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1937).

[7] Aristotle, Physics, 4.2; 209b11-12.

[8] Aristotle, Metaphysics, 13.9; 1086b2-5 (Revised Oxford Translation); cf. EGP 33, D10b.

[9] Aristotle, Politics, 2.6; 1264b26-27.

[10] On the Tübingen School, see most recently Vittorio Hösle’s crisp and insightful overview “The Tübingen School” in Alan Kim (ed.), Brill’s Companion to German Platonism, 328-348 (Leiden and Boston: Brill, 2018).

[11] Aristotle, Metaphysics, 1.6; 987b25-29 (Oxford Revised Translation).

[12] But see Plato, Republic, 524b3-c12 and the final comment’s on Kim, Brill’s Companion, in Bryn Mawr Classical Review, 2019.08.59.

[13] For Terry Penner and Christopher Rowe, see my Ascent to the Good: The Reading Order of Plato’s Dialogues from Symposium to Republic (Lanham, MD: Lexington, 2016), beginning with its Introduction (“Plato and Aristotle”).

[14] See Nicholas D. Smith, “A Problem in Plato’s Hagiography of Socrates.” Athens Journal of Humanities and Arts 5, no 1 (January 2018), 81-103.

[15] See EGP, 33, D37 and D38.

[16] See EGP, 33, D15.

[17] See Gregory Vlastos, Socrates: Ironist and Moral Philosopher (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1991), 91-98; on Xenophon, see 99-106.

[18] EGP 33, D36, D39.

[19] Cf. EGP 33, D44 with Plato, Protagoras, 345d3-346b8.

[20] Plato, Protagoras, 344e8-345b8.

[21] Plato, Meno, 77c1-78b2.

[22] Xenophon, Anabasis, 2.6.23.

[23] On Plato, Meno, 87b2-c3, see Richard Robinson, Plato’s Earlier Dialectic, second edition (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1953).

[24] Aristotle, Politics, 2.6; 1264b30-1265a12.

[25] See Aristotle, Metaphysics, 1.6; 987b14-18 and many other places.

[26] Aristotle, Metaphysics, 1.6; 987b19-22.

[27] See Plato, Republic, 524d8-526b4.

[28] See Aristotle, Metaphysics, 13.7.

[29] Walt Whitman, 1855 “Preface” to Leaves of Grass.

[30] See Heinz Happ, Hyle: Studien zum aristotelischen Materie-Begriff (Berlin and New York: De Gruyter, 1971), 85-208.

[31] Aristotle, Metaphysics, 1.6; 987a32-33 (Oxford Revised Translation).

[32] Plato, Theaetetus, 179d6-181b4.

[33] See ἀκίνητον at EGP 19, D8.31 and D8.43.

[34] EGP, 19, D8.55.

[35] EGP, 19, D8.56-66.

[36] EGP, 19, R12.

[37] EGP, 19, R13.

[38] EGP, 19, D8.61-64.

[39] Plato, Timaeus, 31b4-8.

[40] In addition, cf. Plato, Republic, 528e4-529c3 with Plato, Timaeus, 47a1-4 and 91d6-e1.

[41] Plato, Republic, 516c8-e2.

[42] Plato, Timaeus, 27d5-28a1; cf. Plato, Phaedrus, 262b5-c4; note the references to δόξα and ἀλήθεια.

Also see “§2. “Plato and the ‘Presocratics’”; “§3. Plato and ‘Plato’”; and “§4. The Return to Platonism”