Actually, This is Kansas, Dorothy

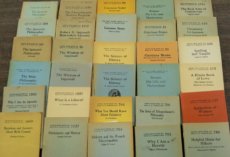

On our desk lie a number of small and rather drab books.

They are 3 ½ by 5 inches, a size that fits nicely into a shirt pocket. The covers are stiff paper, some faded blue, some pale yellow. Each book contains about 64 pages, stapled not bound. The paper is pulp; the print is tiny.

The titles are eclectic: Irish Fairy Tales, Bookbinding Self Taught, Five Essays (by G. K. Chesterton), Debate on Spiritualism (between Conan Doyle and Joseph McCabe), and so on.

Hardly impressive evidence of a major intellectual phenomenon.

In 1915, a man from Philadelphia named Emmanuel Julius, an immigrant’s son, a Jew, an atheist, a socialist, and (wait for it) a reporter moved to Girard, Kansas to work for a socialist newspaper, The Appeal to Reason.

Kansas is not now a bulls-eye of radical reform, but those were other days. Capitalism of the no-holds-barred sort was in command, some people were becoming preternaturally rich, and a great many more were hurting, badly. A lot of them read The Appeal to Reason, which had reached a circulation of 500,000 and published Sinclair Lewis, Jack London, Mary “Mother” Jones, Stephen Crane, and Eugene Debs, although it was now slowly declining.

In 1916, Julius married fellow employee Anna Marcet Haldeman, a former actress, author, and the owner, by inheritance, of a bank, which was handy, because shortly thereafter she lent her husband $25,000 and together they bought the Appeal to Reason. It may have been sinking but its assets included a three-deck, straight-line Goss machine that would print four hundred twelve-page papers, in colors, folded, per minute, and a subscription list of 450, 000 names.

In 1919, Emmanuel Haldeman-Julius (each of the couple had adopted the double-barreled name) sent out an appeal to his subscribers.

Send in $5.00, and H-J would send back, over a space of weeks, fifty small paperback pamphlets, covering a range of authors and topics. Five thousand people responded, and he sent out the books. Then he did another subscription. And another, and another. The covers were initially red, then yellow, and finally blue.

This was the genesis of the “Little Blue Book” series and its success was overwhelming.

The Little Blue Books, priced at five cents, were sold by subscription and in bookstores, drugstores and newspaper kiosks. Laboring people bought them, the middle class bought them, scholars bought them. Haile Salassie bought them, and so did Louis L’Amour, Saul Bellow, Harlan Ellison, and Studs Terkel. Admiral Byrd took copies to the South Pole.

The titles were, as we mentioned, eclectic. The Haldeman-Julii were socialists and remained so, but, while it leaned to social uplift, the list evidenced no narrow partisan focus. The original fifty titles include material by Margaret Sanger, Stevenson, Chekhov — the first Chekhov in English — Thomas Paine, Oscar Wilde, and Balzac (chew on that, River City). There was poetry, belle-lettres, practical topics including mini-school texts and not a little controversial material.

A testimonial:

In the thirties, I taught myself algebra, learning only later that a school text book had many more larger pages, but no more content than my nickel purchase. I also took a stab at geometry and trigonometry. Of course, I had to take regular courses at night for credit to get into college, but it was a breeze. I received credit for algebra, geometry, trigonometry, spherical trigonometry and college algebra in four months!

The project went on into the fifties, but slowly faded. Mrs. H-J died in 1941, Mr. H-J drowned in his own swimming pool (even at a fifth of a cent profit on each copy they did well) in 1951 and the press burned down in 1971.

But by that time the company had published 500,000,000 books. That is half a billion copies. What is one to say in response to such a spectacle?

A number of months ago, we discussed Adler and Hutchins and the Great Books Project, their high and worthy ambitions and their limited success.

The “Little Blue Books” series is an instructive contrast and the lesson it teaches is that in North America, if you want to make an impact, make your product available everywhere, simple, and cheap. Bringing the word down from Olympus or Harvard doesn’t work so well. Up from the streets and out of the garage is how we do it, at least on this side of the Atlantic.

Secondly, in a more philosophical vein: the first decades of the last century, in Anglo-North America, were in a sense the golden era of social contempt. Class divisions and social and ethnic prejudice were powerful and celebrated. Native despised immigrant, white despised colored (any color), educated sneered at the unlettered, and the rich found the poor, at best, amusing.

Now, men may quietly endure poverty, but contempt, as Thomas Aquinas points out, is the father of anger. The social movements of the day addressed this stinging scorn in a variety of ways. One road was politics. Another was to seize the cultural capital of the elite and distribute it among the lower classes. It was along these lines that Emmanuel and Marcet Haldeman-Julius operated, and they deserve to be remembered with praise.

The more praise too, because, behind their actions, were a couple of premises, no longer universally accepted. First, that there was a valid cultural heritage. Secondly, that those denied access to this heritage were deprived of something they ought to have and needed to have. There were things they ought to learn.

That is not dogma today, and we are the worse for it.

What would Voegelin have said? He had done some adult education, after all. We like to think he would have commented, “if we’d had these in Vienna, could be things would of worked out a little better.”