All Donkeys Go to Heaven: “Eo” and Jerzy Skolimowski’s Masterpiece

The 1989 animated musical fantasy All Dogs Go to Heaven humorously poses the question do dogs go to heaven after their life on earth. The dog lover and theologically inclined C.S. Lewis has more seriously pondered the question, which obviously cannot be definitively answered in his field of inquiry. Although, if we were to take the question more seriously, like the question of universal salvation with its ancient tradition in Christian reflection, it could be placed under the category of what some call a theology of hope.

Moving along the broader path of hope, theological or not, we can ask the question whether donkeys go to heaven. Their role in the Nativity Story is well known, no doubt primarily explored in the Gospel apocrypha, as well as in religious folk tradition, which includes the stirring carol “Little Donkey,” poignantly performed by Gracie Fields in the recording of 1959. Not to mention the role of the mild-mannered beast in the Gospel account of the entry of Jesus into Jerusalem during his final days in this world. Few humble beasts of burden would seem more worthy of the heavenly honor.

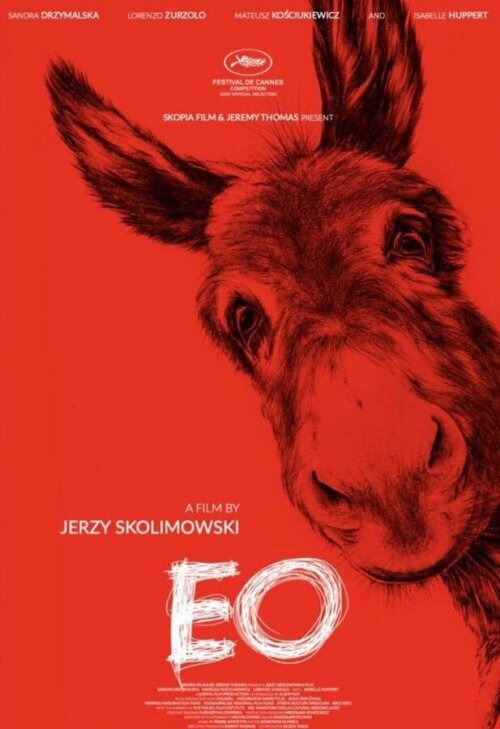

In 1966 the allegorical film Au hasard Balthazar indirectly raises the question. The eponymous Balthazar is a donkey, christened with the apocryphal name of one of the magi by children who love him. Writer/director Robert Bresson shows us the world of his times through the eyes of the dumb beast of burden who witnesses the deeds of those around him. At the very least, as critics note, biblical parables have inspired the filmmaker in this undoubtedly allegorical film.[1] The film, in turn, has inspired the Polish octogenarian filmmaker Jerzy Skolimowski, to look at the contemporary world—more specifically Poland and Italy—through the eyes of yesterday’s beast of burden. The result is the film Eo, released in 2022. Does the question of the ultimate transcendent fate of donkeys come up in any way, shape or form within it?

Skolimowski is a filmmaker whose career goes back to the golden days of the Polish Film School of the 1950s and 1960s, most notably associated abroad with the films of Andrzej Wajda and Roman Polanski. Indeed, early in his career Skolimowski co-wrote the screenplay with Polanski for the latter’s first feature film, Knife in the Water (1962). He made a number of his own films in Poland and abroad until, conflicted with the authorities of the communist regime he left for England. There he made one of his most commercially successful films, Moonlighting (1982), starring Jeremy Irons, about a group of Poles working illegally in London during the time of the Solidarity protests. He returned to Poland after the collapse of the totalitarian communist regime with the end of the Cold War in 1989. Not the most prolific of filmmakers, he has nevertheless worked steadily and received a number of awards, including a lifetime achievement award at the Venice International Film Festival. His film Eo premiered at the 2022 Cannes Film Festival where it was awarded the Jury Prize. It does have a fairly edgy artsy narrative style of a festival film, especially for a number of scene transitions. The film is a Polish-Italian coproduction, and is set in both countries, although predominantly in Poland.

In 1966 donkeys were not all that uncommon yet in rural France, where Bresson’s film begins. This is certainly not the case in contemporary Poland. Skolimowski needed a more atypical excuse for the presence of his animal. He chose a Polish circus as the setting to introduce his mostly silent star with the onomatopoeic name inspired by his—infrequent—braying. On the one hand Eo performed an act with the trainer who sincerely loved him, on the other hand he carried out quotidian tasks, such as pulling carts to a junk yard near the circus grounds. Most of the film consists of the donkey’s eventful journey through different parts of the country until he is shipped to Italy, ostensibly to be slaughtered for equine meat, but with a key interval, from which he escapes, before his tragic fate is fulfilled.

Skolimowski obviously loves nature, and Eo is given several episodes in the wild. But if we are looking for biblical parallels these are not through encounters with a peaceable kingdom. The lion is not yet ready to lie down with the lamb, nor the carnivore with the donkey. But one episode approaching this idyllic state paradoxically takes place when Eo works for a time in a fur farm. Foxes are raised on this farm for their pelts. One night—much of the film takes place at night—the donkey pulls the cart on which the employee that leads him kills the carnivores and places their bodies on the back part of the vehicle. It is the otherwise gentle herbivore that carries out revenge for these violent acts when the occasion arises by kicking the employee with its hind leg in the face and knocking him out.

Obviously this scene has more in common with contemporary animal rights and its abhorrence of the fur trade than with the prophecy in Isaiah, but things are not so simple in the film. It is actually animal rights activists that separate the donkey from the trainer who loves him at the circus ostensibly to save him and other animals from cruelty. The filmmaker evidently feels good intentions are not enough and can even cause harm when thoughtlessly carried out. And of course people can also be cruel and violent to themselves, as the donkey witnesses at different times. Even religion can be toxic, which the animal witnesses in Italy.

In the satirical follow up to the “rescue” of the donkey from the circus he is placed in a center together with magnificent horses, which are treated with special care while the donkey once again is placed behind a cart to help in serving his more appealing to humans’ equine cousins. Yet one scene does have more of a religious, if not biblical, subtext. Shortly after Eo is separated from the circus and the scene above he ends up at a rural center that looks after mentally handicapped children. Here is the only sequence where there are numerous other donkeys. The donkeys are used for therapeutic rides for the children. It is also the place where Eo is treated with great care. The religious element trickles in from the fact that on account of eugenic abortions the population of children with Down’s syndrome has drastically declined in much of Europe. This is not yet the case in Poland, and a fair portion of the children in the sequence are evidently of that genetic syndrome. This in part is a legacy from when religion was stronger in Polish society and the right to life was enshrined more forcefully than in many places in Europe. The sequence at the therapy center is the most serene in the entire film, the children are really happy and the donkey has a genuine haven. Here Skolimowski shows his love for the meek, whether beast or human. But his donkey has a more difficult calling to fulfill.

The haven is lost when his trainer from the circus finds him and comes to say goodbye. Eo had been taken away from the circus quite abruptly and she did not have the chance to do so at that time. The love between them is mutual, and when she parts, as she must, soon after the visit the donkey escapes in a vain attempt to reach her. He ends up lost in the wilderness: but nature offers no haven. And Eo goes alternatively from the wilderness in nature to the wilderness in humanity—sometimes benign, sometimes violent—for the remainder of the film: showing the world to us from the perspective of his innocence.

Bresson is known as a “transcendental” filmmaker,[2] so the question of the afterlife of donkeys seems more appropriate for his masterly film. The same cannot be said for Skolimowski, whose style is rather agnostic. But this down to earth approach to his subject that perhaps leaves little room for allegory does not deny the question of higher values. The selfless love Eo feels for his trainer implies a relationship that is not that far from spiritual. Certainly the donkey seems more fit for heaven than some of the people he comes across. And who’s to say the passage in Isaiah on the peaceable kingdom must be treated fully allegorically? The substance of heaven is much richer and broader than any of us can imagine. Biblical revelation is focused on us because we seem to need so much help to get there, and that has not changed in the least over the millennia.

NOTES:

[1] See Jamie S. Rich, “Au Hasard Balthazar – #297,” Criterion Confessions, November 8, 2008, <http://www.criterionconfessions.com/2008/11/au-hasard-balthazar-297.html.>

[2] See Paul Schrader, Transcendental Style in Film: Ozu, Bresson, Dreyer (New York: Da Capo Press, 1988), 57-108.