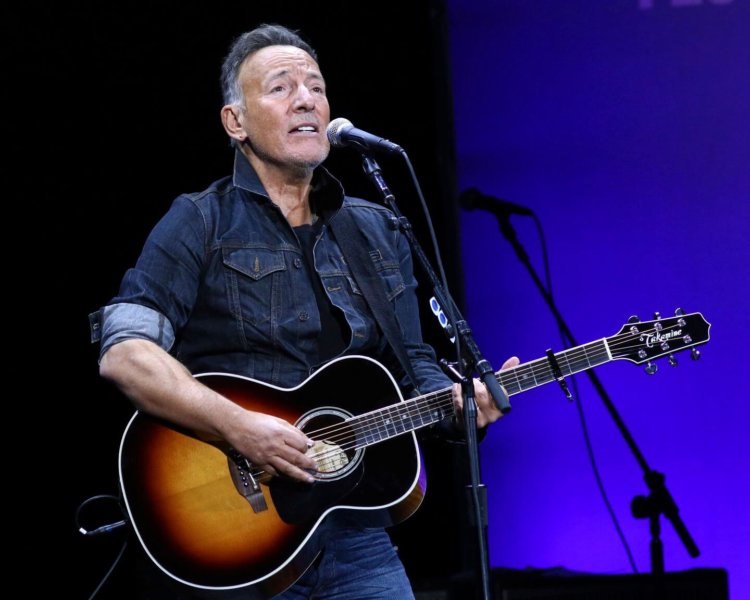

Bruce Springsteen, An American Odyssey

Bruce Springsteen’s recent intimate gig, Springsteen On Broadway, digs deep into the life and lines of The Boss. As I followed along, one of the key themes that broke through, was the theme of departure and return. Or we might say, adventure and coming home again.

We have seen this archetypal pattern throughout history- everywhere from Sanatana Dharma, to Homer’s Odyssey and The Holy Bible. We have also seen it across Springsteen’s canon. Springsteen stands in a long and noble tradition of great storytellers, focused on what truly matters.

I am not primarily going to make an analysis of Springsteen’s work as literature, in terms of more obvious forms. Nor am I going to focus on his self-confessed orthodoxy. Ultimately, I believe he points beyond himself in directions which are worth discerning and want to share some points about his symbolic prowess.

First, the constant re-enchanted themes of Faith, Hope and Love punctuating his work, punch holes in “the buffered self.”

Here is the contrast between the modern, bounded, buffered self and the porous self of the earlier enchanted world. As a bounded self I can see the boundary as a buffer, such that the things beyond don’t need to “get to me,” to use the contemporary expression. That’s the sense to my use of the term “buffered” here and in A Secular Age.” (Charles Taylor, Buffered and Porous Selves)

His hopeful rocker spirit lets a little light in from the transcendent: lighting a path home in an age of mostly manufactured homelessness. We must not suppose that the transcendent is something out there in the ether, uninvolved in our embodied existence in place with particular persons and historical circumstances. That would be a major misstep. Christian transcendence is incarnational. We find the transcendent most often in the immanent. This means, for many of us, finding God and the order of salvation in our daily lives; through the characters we come across, the places we live and travel to, as well all creation.

Second, the journey; sometimes hero and sometimes anti-hero, eventually finds it’s end after many pains and strains of failure, faded dreams and hopeful yearning for more. Home is the end and we walk this road with Springsteen.

Third, Bruce borrows more than is ostensibly apparent from The Gospel and even Gospel music. This is more easily seen in recent albums, which add well-known Gospel staples to contours that have resided in his work from the early days: from “Call and Response,” to lyrical tales of salvation from dull and humdrum existence.

Regarding this third point, to avoid missing a major neglected theme in Springsteen’s music and our musical tradition, let us consider Bruce Ellis Benson’s notes on the call and response motif.

In his book, Liturgy as A Way Of Life, he rethinks what it means to be artistic. Benson recovers the ancient Christian idea of presenting oneself to God as a work of art. Rather than viewing art as practiced only by the few, Benson argues that we are all called by God to be artists. This long excerpt brings the point home:

I think it is safe to say that there is nothing more basic to human existence than the call and response structure. It is, quite simply, the very structure of our lives.

If you’ve never read Scripture in terms of call and response, you may not have noticed just how frequently it occurs. It’s virtually everywhere. Consider how the world comes into being: God says, “‘Let there be light’; and there was light” (Gen. 1:3). So, the very beginning of the world is the result of a call—God calls, and the world suddenly comes into existence.

The pattern does not end there: it continues in all of God’s dealings with the world. God calls to Adam and Eve in the garden (his call to them after partaking of the fruit is particularly poignant, for now they are reluctant to respond). Then, in the midst of a broken humanity, God calls Abraham to go to a foreign land where he will make Abraham’s descendants into a new nation (Gen. 12).

In Gen. 22, we get both the call and the classic form of the response. God calls out: “Abraham!” And Abraham responds: “Here I am” (Gen. 22:1). Abraham gives what turns out to be the standard biblical reply, saying (in Hebrew) hinneni. But what does hinneni mean?

In effect, Abraham humbly says, “Here I am, your servant. I am at your disposal. Tell me what you want me to do!” This is a particularly moving passage, for God goes on to say, “Take your son, your only son Isaac, whom you love, and go to the land of Moriah, and offer him there as a burnt offering on one of the mountains that I shall show you” (Gen. 22:2).

To say that Abraham must have been surprised would be a huge understatement: God is asking him to sacrifice the very son through whom God has promised to build a great nation. But Abraham does exactly what God tells him to do, and the book of Hebrews celebrates him for his faith and trust in God (Heb. 11:17).

This structure of call and response continues in Scripture. When God calls to Moses from the burning bush, God says: “Moses, Moses!” To that call, Moses replies: “Here I am” (Exod. 3:4). Similarly, God calls to Samuel who responds: “Speak, for your servant is listening” (1 Sam. 3:10).

Indeed, Mary says to the angel that visits her: “Here am I, the servant of the Lord; let it be with me according to your word” (Luke 1:38).

Perhaps the ultimate call in the Hebrew Bible is: “Hear, O Israel: The LORD is our God, the LORD alone” (Deut. 6:4). In any case, we are constantly being called by God to give the reply “here I am,” which signals our utter openness to God’s command. Again, once one notes this structure, one sees it throughout all of Scripture. And it soon becomes clear that call and response is the most fundamental structure to our lives.

The author then encourages us to look towards American gospel music, which is a continued well of inspiration for our subject, Bruce Springsteen:

Consider the classic spiritual:

Hush! Hush! Somebody’s calling my name

Hush! Hush! Somebody’s calling my name

Hush! Hush! Somebody’s calling my name

O my Lord, O my Lord, what shall I do?

Isn’t this always the case? Somebody’s calling my name. I hear the call and I’m faced with questions such as: What shall I do? What shall I do? What shall I do? Who is this I who is being called? And what happens to this I in being called?

Even though this pattern of call and response goes back at least as far as creation, there is no one call, even in the creation narrative.

Instead, there are multiple calls—calls upon calls—and thus responses upon responses, an intricate web that is ever being improvised, resulting in a ceaseless reverberation of call and response.’’ (Bruce Ellis Benson, Liturgy as a Way of Life, 2013)

So, Benson re-envisions art as the very core of our being: we are God’s own art, and God calls us to improvise as living and growing works of art. Springsteen embodies this sentiment until today as a man over seventy and testifies in the same spirit.

We’ll discuss this theological foundation in greater detail later, with special focus on Springsteen’s Catholic imagination but should always keep these motifs in mind, in order to appreciate his standing as an artist.

In the Beginning

Bruce Springsteen was born in New Jersey, USA. But it was later, in the clubs and halls around the north east states, that the man we know as The Boss was born. The Springsteen legend took shape with his early album Greetings from Asbury park and the mythic origins of the E Street Band.

It was in the mid-seventies however when this scruffy and erratic troubadour began a long adventure as a man searching for true meaning. In a quest now known around the world, immortalized in story and song. Springsteen himself has said, echoed by many around him, that the transcendent adventure away from home properly began with ‘Born to Run’. It was to be a long time before he would return home again.

Different from Greetings from Asbury Park, N.J. and The Wild, the Innocent & the E Street Shuffle, Born to Run includes fewer specific references to places in New Jersey. This captures a shift in character and was intended to play a part in making the songs more identifiable to a wider audience. However, neither then nor ever after did Bruce abandon his roots. They have exercised his imagination and been a filter for inspiration across his musical endeavors. This change of focus mainly demonstrated a positive change in how Springsteen related stories.

Bruce has referred to a maturation in his lyrics at this time, naming Born to Run “the album where I left behind my adolescent definitions of love and freedom—it was the dividing line.” (Mark Richardson, “Bruce Springsteen Born to Run: 30th Anniversary Edition Review”, 2005)

Oh honey, tramps like us

Baby, we were born to run

Come on with me, tramps like us

Baby, we were born to run (Born To Run, from the album Born To Run, 1975)

Hey pretty darling, don’t wait up for me

Gonna be a long walk home

It’s gonna be a long walk home

It’s gonna be a long walk home (Long Walk Home, from the album Magic, 2007)

In Springsteen On Broadway, he finally makes it clear that he’s made it home. But this was not until 2018. The journey between then and now has seen the world many times over. Bruce achieves a clear expression of ultimate contentment in 2018’s autobiographical show, by way of humorous reference to his current home in New Jersey, which is “ten minutes from (my) hometown.” (Bruce Springsteen, Springsteen On Broadway, 2018)

In this moving musical memoir, Bruce shares stories about what it means to find, make and keep a home: finding his place, detailing in pulling emotion his happy marriage with Patti and resolved relationship with his father. These resolved relationships and return home have been a long time in the making.

Adventure and Home in History

Adventure and home extend far beyond the borders of New Jersey and the USA. These motifs of human nature are constant across cultures and have helped us erect a most high and holy religious edifice from ancient India, to the Greece of Homer and The Holy Scriptures:

Let’s begin our sojourn in what is now India and with a glance to her epic Ramayana. The Ramayana is an ancient Sanskrit epic which follows Prince Rama’s quest to rescue his beloved wife Sita from the clutches of Ravana with the help of an army of monkeys. It is traditionally attributed to the authorship of the sage Valmiki and dated to around 500 BC to 100 BC.

Comprising 24,000 verses in seven cantos, the epic story of adventure contains the teachings of the very ancient Hindu sages. It is one of the most important literary works of India, greatly influencing art and culture across the entire Indian subcontinent and across all of South East Asia. With versions of the story also appearing in the Buddhist canon from a very early date.

The story of Rama has constantly been retold in poetic and dramatic versions by some of India’s greatest writers and in narrative sculptures on temple walls. It is one of the staples of later dramatic traditions, re-enacted in dance-dramas, village theatre, shadow-puppet theatre and the annual Ram-lila (Rama-play). It is a staple tale in Hindu homes still today and expresses what it means to live a meaningful life by regaling us with tales of adventure and return.

Then there is the archetypal story of ancient Greece, The Odyssey, where “There is Odysseus, a vivid, viable, versatile, multifarious man, the man by whose agency alone Achilles is admitted to blood and voice, the man who made the odyssey—a poet.

And so, it is shown that the “Odyssey,” a poem about a poet, is a work of reflection.” (Eva Brann, The Poet of the “Odyssey”, 2019) We concur with Brann that this epic poem is a work of reflection but add that it is most certainly not a work of mere ‘self-reflection’, like many creations which our present age foolishly fawn over.

The story of stories, The Holy Christian Scriptures, places the archetypal tale of adventure and return home at the foot of eternity. We are given a clear image of this in the story of the prodigal son, but it is at the heart of the entire Holy Bible.

It is in light of eternity that everything takes on fullest significance. It is in this light that Bruce’s art, and all great art, might serve to reflect our noble destiny.

The perennial portions of his body of work do just that- the wonderful zest for fine romance of Rosalita, the aching faith in the promised land, redeemed relationships with loved ones and witness to resurrection, displayed in songs such as The Rising. Springsteen taps into the epic energies of poetry’s storehouse.

1 Timothy 6:12 Fight the good fight of the faith. Take hold of the eternal life to which you were called when you made your good confession in the presence of many witnesses.

Eugene Peterson (The Bible, Poetry, and Active Imagination, 2018) has captured this sense of adventure and epic poetry in The Holy Bible:

“All the prophets were poets. And if you don’t know that, you try to literalize everything and make shambles out of it. A metaphor is really remarkable kind of formation, because it both means what it says and what it doesn’t say.

And so those two things come together, and it creates an imagination which is active. You’re not trying to figure things out; you’re trying to enter into what’s there.”

It is with a symbolic lens that we see most clearly the appeal of the boss to the many and the few. This is an artist who has enjoyed critical and commercial success from the seventies until today. Springsteen, for good reason, sparks an interest in all ages and across demographics.

We’ve noted the early mythic formation of The E Street band, whose tales are told on stage with great imaginative appeal in concerts which carry the audience away. However, there have been a number of twists and turns along the road – from the heady success of Born To Run to kick off the adventure to later more sable creations such as Darkness On The Edge Of Town and Nebraska.

The Nebraska album reaches deep into the American landscape and mind in equal measure, even as subterranean as Charles Starkweather. He was a serial killer involved in murdering almost a dozen people with his minor girlfriend, featured in Terence Malick’s Badlands; which inspired Nebraska, alongside the fiction of Springsteen’s fellow Catholic writer Flannery O’Connor.

The titular song Nebraska’s final line, which involves the narrator giving his reason for the murders, reads “I guess there’s just a meanness in this world.” This is comparable to the climax of O’Connor’s story “A Good Man Is Hard to Find”, where the killer proclaims in harsh relativism, “it’s nothing for you to do but enjoy the few minutes you got left the best way you can — by killing somebody or burning down his house or doing some other meanness to him. No pleasure but meanness.” (June Skinner Sawyers, Tougher Than the Rest: 100 Best Bruce Springsteen Songs, 2006)

What this means, among other things, is that Springsteen is open to the drama of salvation in all it’s gritty detail. The enchanted world mentioned by Taylor before: A transcendent world of good and evil, refreshingly resistant to common temptations to explain evil away by reducing it to a deadening illogical determinism, or pompous popular psychology.

This simplistic determinism has been injected into our present age, attacking every limb of our cultural body like a deadly virus. There is scant respect for the freedom of God or Man:

“Physical determinism is the notion that all events, including thoughts and actions, are the result of cause and effect. Each effect is the result of a prior cause. Each effect is also the cause of some new effect, creating an endless causal chain.’’ (Richard Cocks, The Illogicality of Determinism, 2019)

Later on, eighties Springsteen brought us re-enchanted musical dramas, flowing from The River to the iconic Born in The USA and lesser known, but particularly impressive, Tunnel of Love. Running on to Wrecking Ball and Western Stars more recently.

Stamped indelibly in each work however have been Christian virtues of Faith, Hope and Love. With this tripartite lamp, Springsteen has shone light on the perils, limitations and opportunities of life in small town USA, from east to west, to the struggles of living on a hard land; to the death and destruction of war and desecration of romantic love, marriage and family life. Before breeching a way out.

Adventure and Coming Home in Music

A less obvious feature of the tale is how Bruce’s musical composition itself is stamped through with Hope. Even when the lyrics appear to lend themselves to despair.

Famously in the Born in the USA album, The Boss shared tales of lamentation paired with triumphant rock music. The intent, it seems, was to cut through the suffocating cloak of nihilism.

This hopeful defiance partakes in a greater narrative of adventure and coming home, which is even built into our finest music. We’ve mentioned the call and response structure before and appreciate that it’s central to the joy of a Springsteen concert. The underlying music tells stories of its own. Jeremy Begbie (Resounding Truth, 2007) illustrates the point by describing the tension and resolution typical of our great musical canon. Bruce’s pieces take their place in this Christian canon.

We see and hear this adventure and fulfillment in both the music and story of Springsteen’s The Promised Land.

Well there’s a dark cloud rising from the desert floor

I packed my bags and I’m heading straight into the storm

Gonna be a twister to blow everything down

That ain’t got the faith to stand its ground

Blow away the dreams that tear you apart

Blow away the dreams that break your heart

Blow away the lies that leave you nothing but lost and broken-hearted

The dogs on main street howl

‘Cause they understand

If I could take one moment into my hands

Mister, I ain’t a boy, no, I’m a man

And I believe in a promised land

And I believe in a promised land

And I believe in a promised land (From The Darkness On The Edge Of Town album, 1978)

Coming Home In The Present Age

The characters in Springsteen’s stories are all searching for home in what is perceived to be a homeless age. An age of self-inflicted despair, that Kierkegaard labelled “The Present Age.” (Søren Kierkegaard, Two Ages: A Literary Review, USA: Princeton University Press, 2009)

It is argued that Kierkegaard’s writings testify to the modem fixation upon the ‘self’, whilst proposing a theological anthropology that constitutes an attempted recovery from the modem drive for self-possession via isolated introspection.

It is the failure of the self to grasp itself through self-reflection that engenders the dialectics of anxiety, melancholy’, and despair which potentially initiate the self’s authentic self-becoming before God.” (Simon D. Podmore, Kierkegaard And The Self Before God, 2011)

Springsteen’s work calls us away from ‘isolated introspection’ and calls us toward those transcendent virtues of faith, hope and love which we discussed before.

Another lesser-known American icon, Wendell Berry, has described and decried this metaphysical and literal homelessness over a long career. This contrarian farmer, poet and writer, mirrors Springsteen at his storytelling best. He speaks of our place in the cosmos, and on earth, in ways which respect the ‘democracy of the dead.’

“Tradition means giving votes to the most obscure of all classes, our ancestors. It is the democracy of the dead. Tradition refuses to submit to the small and arrogant oligarchy of those who merely happen to be walking about.’’ (GK Chesterton, Orthodoxy, 1908)

Part of the appeal and transcendent brilliance of Bruce’s oeuvre lies in his same respect for good traditions. He looks backwards and forwards, from a place centred on communion. It is in stances like this that Catholics, and Bruce, can see that he is “still on the team.” (Tom Deignan, Proud Irish American Bruce Springsteen says deep down he’s still Catholic, 2018)

The place of generations is pivotal to Springsteen’s great appeal. Again, in an age compulsively centered in introspective isolation, Berry reminds us, “Throughout most of our literature, the normal thing was for the generations to succeed one another in place. The memorable stories occurred when this succession failed or became difficult or was somehow threatened.

This brings us back to the Holy Bible, which gives the generations of man their ultimate meaning in The Logos.

Berry reminds us “The norm is given in Psalm 128, in which this succession is seen as one of the rewards of righteousness:

“Thou shalt see thy children’s children, and peace upon Israel.”

The longing for this result seems to have been universal. It presides also over The Odyssey, in which Odysseus’ desire to return home is certainly regarded as normal. And this story is also much concerned with the psychology of family succession.

Telemachus, Odysseus’ son, comes of age in preparing for the return of his long-absent father; and it seems almost that Odysseus is enabled to return home by his son’s achievement of enough manhood to go in search of him.

The bond between father and son in Springsteen echoes the ancients.

Long after the return of both father and son, Odysseus’ life will complete itself, as we know from Teiresias’ prophecy in Book XI, much in the spirit of Psalm 128:

A seaborne death

soft as this hand of mist will come upon you

when you are wearied out with sick old age,

your country folk in blessed peace around you.

The Bible makes much of what it sees as the normal succession, in such stories as those of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob, or of David and Solomon, in which the son completes the work or the destiny of the father.

The parable of the prodigal son is prepared for by such Old Testament stories as that of Jacob, who errs, wanders, returns, is forgiven, and takes his place in the family lineage.” (Wendell Berry, What Matters?, 2004)

A surprising co-heir to Springsteen’s beautiful tradition is Roger Scruton. He places the emphasis on home in a way that sits comfortably with what Springsteen has been preaching for roughly fifty years:

. . . rational beings “strive to achieve order in their surroundings and to be at home in their common world” (Roger Scruton, Beauty, 2009). Feeling “at home” in the world is a universal human longing.

To him, a true conservative, in contrast to the reactionary, will not strive to make the world according to his preferences, but will adapt to the world without surrendering his values.

This is a tall order that requires engagement with and civility towards those who hold different beliefs, but it is an attitude that is needed in a world torn apart by political ideologies, a way for rational beings to create a “home in their common world.”

Perhaps there is a chance for a common language given that “the beautiful and the sacred are adjacent in our experience, and that our feelings for the one are constantly spilling over into the territory claimed by the other” (Roger Scruton, Beauty, 2009). (From Tina McCormick, Coming Home in Scrutopia, 2018)

True And Misadventures

You only live once — if then.

Life is short, and it can be as easily wasted as lived to the full. In the midst of our harried modern world, how do we make the most of life and the time we have?

In these fast and superficial times, it is tempting to seize material wealth or political power. To offer and expect salvation in the political order. But this is not enough, and our great tradition constantly calls us on a greater adventure. Springsteen’s Nebraska album lists, in the spirit of Augustine, a reverie of idols which cannot satisfy our hearts. From a mansion on a hill, to places like Atlantic City that fail and fall away, further and faster the more we seize upon them.

“Thou hast made us for thyself, O Lord, and our heart is restless until it finds its rest in thee.” (St Augustine, The Confessions, 2008)

Os Guinness, in a brilliant recent book, Carpe Diem Redeemed, calls us to nobler consequential living. Prodding us to return to transcendent Christian virtues. The same can be said for The Boss, who longs for and invites us to the promised land and the rising, even as towns fall apart, families crumble and lands are desecrated.

In strong contrast to many eastern and secularist views of time, Os Guinness reorients our very notion of history; not as cyclical nor as meaningless, but as linear and purposeful. The hopeful expectation of Springsteen truly makes sense within this tradition.

In the Judeo-Christian tradition, time and history are meaningful, and human beings have agency to live with freedom and consequence in partnership with God. This tradition calls us back home, which is with God.

Thus, we can seek to serve God’s purpose for our generation, read the times, and discern our call for this moment in history. Our time on earth has significance. Live rightly, discern the times, and redeem the day. Our subject speaks to redemption.

However, at this point I would like to decry Springsteen’s political progressivism, which seeks to “immamentize the eschaton,” or bring heaven to earth. This is not what we want, and I believe this is the greatest perversion of his life and work.

He underestimates the dangerous perversion of placing faith in the political order and should take another step with Saint Augustine. Philosopher Eric Voegelin pulls us away from this this dangerous precipice. (The New Science of Politics, 1987):

The death of the spirit is the price of progress. Nietzsche revealed this mystery of the Western apocalypse when he announced that God was dead and that He had been murdered.

This Gnostic murder is constantly committed by the men who sacrificed God to civilization. The more fervently all human energies are thrown into the great enterprise of salvation through world–immanent action, the farther the human beings who engage in this enterprise move away from the life of the spirit. And since the life the spirit is the source of order in man and society, the very success of a Gnostic civilization is the cause of its decline.

A civilization can, indeed, advance and decline at the same time—but not forever.

There is a limit toward which this ambiguous process moves; the limit is reached when an activist sect which represents the Gnostic truth organizes the civilization into an empire under its rule. Totalitarianism, defined as the existential rule of Gnostic activists, is the end form of progressive civilization.

Whilst Bruce Springsteen most often takes us beyond the shallow waters of the present age, and speaks with commendable ultimate hope, he can on occasion slip into the lamentable waters of political optimism. However, as we can see, this is not the main measure of The Boss.

Everybody’s Got A Hungry Heart

The ancient Hebrew word for heart is “‘Lev.” The deep and wide description of heart given by The Scriptures can help us understand what it means to have a hungry heart. There is no biblical word that captures better the essence of human thought, feeling, and desire than this rich and wonderful word, heart. (The Bible Project, 2019)

The heart of Springsteen is hungry ultimately for home:

It ought to be easy ought to be simple enough

Man meets woman and they fall in love

But the house is haunted and the ride gets rough

And you’ve got to learn to live with what you can’t rise above if you want to ride on down in through this tunnel of love. (From the Tunnel Of Love album, Bruce Springsteen, 1987)

There is no home without loved ones, family and friends. Ultimately, there is no home without God. This is a lesson that Bruce Springsteen has learned in his own life and proffered to others.

Bruce has made his peace with God and his earthly father. In settling down with Patti and setting up a home, he has further mirrored the archetypal virtues of manliness. This way of life offers hope and a real alternative to, and from, the tragic circumstances of the restless characters in Born To Run, Nebraska and other tales. It escaped him once, but not when he received a second chance.

A key part of the problem with our present age is, and has been for some time, the desecration of marriage and family life. Even if Springsteen’s politics don’t lend themselves to the flourishing of the family and marital love, The Boss does offer himself as a model for long-term committed love, focused on a long obedience in the same direction. (Eugene Peterson, A Long Obedience in the Same Direction, 2019)

Springsteen On Broadway’s duet with Patti is one of the more touching moments and speaks the truth of a marriage made and kept in committed love. The secular idols of marriage and the family in service to twisted self-interests have failed. It is not enough to make them a ‘haven in a heartless world’. (Christopher Lasch, Haven in a Heartless World, 1985)

We must nestle both in the greater restful story of the heart finding a home and serve others in and through marriage.

Lasch, happily married with children before his untimely death in the mid-nineties, prophesied against the perversions of marriage and the family.

A liberal society that reduced the functions of the state to the protection of private property had little room for the concept of civic virtue. Having abandoned the old republican ideal of citizenship along with the republican indictment of “luxury,” liberals lacked any grounds on which to appeal to individuals to subordinate private interest to the public good.

But at least they could appeal to the higher selfishness of marriage and parenthood. They could ask, if not for the suspension of self-interest, for its elevation and refinement. Rising expectations would lead men and women to invest their ambitions in their offspring.

The one appeal that could not be greeted with cynicism or indifference was the appeal later summarized in the twentieth-century slogan, “our children: the future” (a slogan that made its appearance only when its effectiveness could no longer be taken for granted).

Without this appeal to the immediate future, the belief in progress could never have served as a unifying social myth, one that kept alive a lingering sense of social obligation and gave self-improvement, carefully distinguished from self-indulgence, the force of a moral imperative.” (Christopher Lasch, The True And Only Heaven, 1991)

Let us return home to the Christian mystery of Marriage. This Holy mystery is not merely about political or emotional expediency, nor self-improvement. In contrast to the idols that Lasch combats above, marriage in Christ is iconic. A distinction made clear in the Orthodox theology of marriage:

In the Orthodox tradition, consent was less pivotal in defining a marriage. The clerical officer (bishop or priest) representing the Church, blesses and marries the bride and groom, and the couple is by this act bonded as husband and wife to Christ and the Church.

The conjugal love union, and not consent or contract, is understood to be the very heart of marriage. Marriage is a sacrament of love, but not just any sort of love.

This love union is founded and grounded in God’s will, in His creative act of making mankind male and female, so that, through their love for each other and their sexual union, a man and a woman may become “one flesh.”

Consent and contract more properly belong to betrothal (though Orthodox marriage rites include consent often by inference – and in some cases, as in the Slavonic version of the Byzantine rite, explicitly)” (Dr Vigen Guroian, If Love Has Won, Has Marriage Lost?, 2015)

It was not long after the success of Born in The USA and the adventures around the world, that Bruce came to a startling revelation to commence this journey. The Boss was ready for the long obedience in the same direction that we have described. He didn’t know where it was going to end but made the choice to commit, in spite of hurt and failure, and it lasts:

I didn’t know it then but soon we’d be finished for a long while. The tour also was the beginning of something, a final surge to try to determine my life as an adult, a family man, and to escape the road’s seductions and confinements.

I longed to finally settle in, in a real home, with a real love. I wanted to lift upon my shoulders the weight and bounty of maturity, then try to carry it with some grace and humility. I’d worked to get married; now, would I have the skills, the ability . . . to be married?”

This brings us back to Homer and our odyssey:

“The Odyssey is a tale of a journey home. More importantly, the journey home is not merely to a piece of land to settle and call home. It is a journey to an already established home and to a family. Home, for Odysseus, is not simply (or merely) Ithaca. Home is where Penelope and Telemachus are; home is where Odysseus’ family resides. Home is where Odysseus’ roots are.” (Paul Krause, Homer’s Epic of The Family, 2019)

The same resolution is recounted regarding Bruce’s father, with whom he reconciled after long periods of masculine friction. This is expressed in the On Broadway show as well as in songs dedicated to this man and their relationship. After solving these problems, Springsteen became freer to manifest the masculine energies in their transcendent vigour. Giving new life, and a place in continuity to the artist and man:

“True humility, we believe, consists of two things. The first is knowing our limitations. And the second is getting the help we need.” (Robert L. Moore, King, Warrior, Magician, Lover, 1991)

Springsteen’s dreams and promises of finding ultimate meaning were ready to be fulfilled. Andrew Greeley traces the tensions of the Catholic imagination throughout Bruce’s career, which in this latter part of his life have found incarnate resolution:

. . . he begins to imagine that he can escape his “town full of losers,” if only he can convince a girl (of course) to join him in the front seat (at least). She is named Mary (of all things) and his moment of possible enlightenment occurs when he sees her dancing across her front porch to the sound of Roy Orbison singing for the lonely.

Suddenly, redemption seems just that simple. Yet in Springsteen’s New Jersey that is usually how dreams get made. In such a moment, a world, or at least a highway, seems about to open. The long-term prospects might be dim (he does not seem to have a reliable source of gas money).

He is “no hero,” as anyone can tell, and the only “redemption” he can offer is beneath his car’s “dirty hood.”

We move from faith and hope to love, in concentric circles:

The path to salvation might turn out to be nothing more exotic than the New Jersey Turnpike. Yet in this moment, hope is enough. In fact, it is everything. It is time to take a chance.” From the time of Born To Run.

Now, “Springsteen has arrived at a more mature and more compelling understanding of our collective need for a communal expression of struggle and hope and, at the same time, his own need as an artist for the ultimately solo act of stark reappraisal, in a continuing and partially ritualized return to the origins of his dreams and his beliefs.

Ultimately, the recent “Springsteen on Broadway is subtly yet determinedly confessional.” (Brian P. Conniff, The Enduring Catholic Imagination of Bruce Springsteen, 2018)

Despite the odd flirt with idolatry in his politics even into his old age, The Boss continues to bear faithful and impressive witness to the transcendent and properly ‘eschatological’ longing for home. Which finds real iconic and partial fulfillment on our earth. While we are still anticipating a new heaven and new earth to make it full and lasting.

The continued sense of adventure and quest for home in Springsteen’s music points to, and partakes in, the ultimate story of Man. Which the Holy Bible describes as directed ultimately toward our home in The Kingdom, with the family of God. Springsteen tells stories, and writes music, that are woven into this larger tapestry:

The biblical story is not only critical of other stories but also hospitable to other stories. On its way to the kingdom of God it does not abolish all other stories but brings them all into relationship to itself and its way to the kingdom.

It becomes the story of all stories, taking with it into the kingdom all that can be positively related to the God of Israel and Jesus. The presence of so many little stories within the biblical metanarrative, so many fragments and glimpses of other stories, within Scripture itself, is surely a sign and an earnest of that.

The universal that is the kingdom of God is no dreary uniformity or oppressive denial of difference, but the milieu in which every particular reaches its true destiny in relation to the God who is the God of all because He is the God of Jesus.’ (Richard Bauckham, Bible and Mission: Christian Witness in a Postmodern World, 2004)

We’ve shared a number of elemental themes stitched throughout Springsteen’s musical artwork. It is because of these memorable motifs and their moving impact that we judge Springsteen to be like Homer, and why we see his long and meandering journey as a true American odyssey.

References

Augustine, Saint (2008) The Confessions (Oxford World’s Classics), Reprint edition edn., UK: OUP Oxford .

Bauckham, Richard (2004) Bible and Mission: Christian Witness in a Postmodern World, USA: Baker Academic.

Begbie, Jeremy (2007) Resounding Truth (Engaging Culture): Christian Wisdom in the World of Music, USA: Baker Academic.

Benson, Bruce Ellis (2013) Liturgy as a Way of Life: Embodying the Arts in Christian Worship, USA: Baker Academic.

Berry, Wendell (2010) What Matters?, USA: Counterpoint.

Bible Study Tools’ Staff (2019) Bible Verses about Adventure , Available at: https://www.biblestudytools.com/topical-verses/bible-verses-about-adventure/ (Accessed: 26th November 2019).

Brann, Eva (2019) The Poet of the “Odyssey”, Available at: https://theimaginativeconservative.org/2019/06/poet-odyssey-eva-brann.html (Accessed: 26th November 2019).

Chesterton, GK (2018) Orthodoxy, USA: CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform

Cocks, Richard (2019) The Illogicality of Determinism, Available at: https://voegelinview.com/the-illogicality-of-determinism/ (Accessed: 1st December 2019).

Conniff, Brian P. (2018) The Enduring Catholic Imagination of Bruce Springsteen, Available at: https://www.americamagazine.org/arts-culture/2018/04/18/enduring-catholic-imagination-bruce-springsteen (Accessed: 2019).

Deignan, Tom (2018) Proud Irish American Bruce Springsteen says deep down he’s still Catholic, Available at: https://www.irishcentral.com/roots/history/irish-american-boss-bruce-springsteen-catholic (Accessed: 1st December 2019).

Greeley, Andrew (1988) Andrew Greeley on the Catholic Imagination of Bruce Springsteen, Available at: https://www.americamagazine.org/issue/100/catholic-imagination-bruce-springsteen (Accessed: 2019).

Guinness, Os (2019) Carpe Diem Redeemed: Seizing the Day, Discerning the Times, USA: IVP Books.

Guroian, Vigen (2015) If Love Has Won, Has Marriage Lost? An Orthodox Response to Obergefell v. Hodges 1, Available at: https://www.aoiusa.org/if-love-has-won-has-marriage-lost-an-orthodox-response-to-obergefell-v-hodges1/ (Accessed: 2019).

Krause, Paul (2019) Homer’s Epic of the Family, Available at: https://voegelinview.com/homers-epic-of-the-family/ (Accessed: 26th November 2019).

Lasch, Christopher (1995) Haven in a Heartless World: The Family Besieged, 2nd edn., USA: W. W. Norton & Company; New Ed edition.

Lasch, Christopher (2013) The True and Only Heaven: Progress and Its Critics , 2nd edn., USA: Norton.

McCormick, Tina (2018) ‘Coming Home in Scrutopia : A happy week with Roger Scruton’, Available at: https://theimaginativeconservative.org/2017/09/roger-scruton-coming-home-scrutopia-tina-mccormick.html (Accessed: 26th November 2019).

Moore, Robert L. (1991) King, Warrior, Magician, Lover: Rediscovering the Archetypes of the Mature Masculine , 2nd edn., USA: HarperOne.

O’ Connor, Flannery (2019) A Good Man Is Hard to Find and Other Stories, USA: Mariner Books.

Peterson, Eugene (2018) The Bible, Poetry, and Active Imagination, Available at: https://onbeing.org/programs/eugene-peterson-the-bible-poetry-and-active-imagination-aug2018/ (Accessed: 26th Novemeber 2019).

Peterson, Eugene (2019) A Long Obedience in the Same Direction: Discipleship in an Instant Society , Commemorative edition edn., USA: IVP Books.

Podmore, Simon D. (2011) Kierkegaard and the Self Before God: Anatomy of the Abyss, USA: Indiana University Press.

Richardson, Mark (November 18, 2005). “Bruce Springsteen Born to Run: 30th Anniversary Edition > Review”. Pitchfork. Retrieved 1 June 2006.

Sawyers, June Skinner (2006). Tougher Than the Rest: 100 Best Bruce Springsteen Songs. Omnibus Press.

Scruton, Roger (2011) Beauty: A Very Short Introduction, UK: OUP Oxford.

Springsteen, Bruce (1975) Born To Run, CD-ROM, USA: Sony Music Cmg.

Springsteen, Bruce (1978) Darkness On The Edge Of Town, CD-ROM, USA: Sony Music Cmg.

Springsteen, Bruce (1982) Nebraska, CD-ROM, USA: Columbia.

Springsteen, Bruce (1987) Tunnel Of Love, CD-ROM, USA: Columbia.

Springsteen, Bruce (2002) The Rising, CD-ROM, USA: Columbia.

Springsteen, Bruce (2012) Wrecking Ball, CD-ROM, USA: Columbia.

Springsteen, Bruce (2016) Born To Run, 1st edn., UK: Simon & Schuster UK.

Springsteen, Bruce. (2007) Magic, CD-ROM, USA: Columbia.

Springsteen, Bruce. (2018) Springsteen On Broadway, CD-ROM, USA: Columbia.

Taylor. C (2008) Buffered and porous selves, Available at: https://tif.ssrc.org/2008/09/02/buffered-and-porous-selves/ (Accessed: 2nd December 2019).

The Bible Project (2019) Lev / Heart, Available at: https://thebibleproject.com/videos/lev-heart/ (Accessed: 1st December 2019).

Voegelin, Eric (1987) The New Science of Politics , New edition edn., USA: University of Chicago Press.