Caravaggio’s Light and the Essence of Christianity

Whence comes light in the paintings of Caravaggio? What is the nature of this light? What does it illuminate and why does it do so? Let us come to terms with these questions so as to arrive at an understanding of our painter’s production without being blinded by modern prejudices, or by everything that we might believe to know already about Caravaggio and that could thereby prevent us from discerning the proper meaning of the painter’s work.

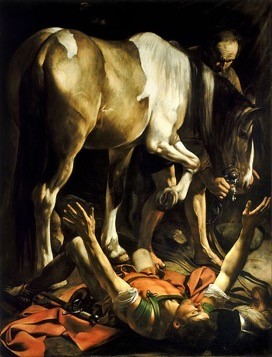

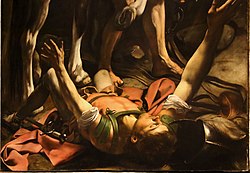

So as to best tackle our questions, let us examine two among our painter’s most famous canvases, namely the Calling of St. Matthew (1600) and the Conversion of Saul (particularly its second version from 1601). To begin, we notice that light does not function in the identical manner in our two paintings.

In St. Matthew’s Calling light is certainly not “natural” in the respect that it does not come from the sun. An open wooden shutter draws our attention to the only window on the scene: no light comes through the window. Light enters instead with the Christ in a large ray incarnated by the gesture of Christ, whose hand indicates a young Matthew plunged in mundane life to the point where he does not notice in the least the entrance of the Christ, that is of incarnate light, accompanied by St. Peter.

Blinded by matter, the young man ignores his veritable calling. That being said, there are three other characters who, although mundane, show themselves conscient of the irruption of light in the room that would otherwise remain steeped in darkness. The three men wear hats that we might consider bourgeois (the two younger men boast a heckle of feathers over their own hats); they turn, at least with their gaze, towards the Christ, betraying an ambivalent attitude insofar as they seem to draw away from the incarnate light with gestures suggesting aversion to the light’s Calling. As for St. Matthew, his face is steeped in shadow, or rather darkness, under the apparent patronage of an old man who could very well be Matthew himself in his future old-age.

Now, returning to the question of light, we could be tempted to accept that the light incarnated by the Christ is unequivocally the Holy Ghost. The problem with this conclusion is that the Holy Ghost as such should not be discerned by those it does not call, namely those who are not blessed with faith. Nevertheless, the Holy Ghost manifests itself to faithless people under the guise of law.

To better understand the distinction at hand, let us consider Caravaggio’s Conversion of Saul or Saint Paul on the road to Damascus. In this second 1601 version of the painting, light is altogether unnoticed by Saul’s groom or servant. The light is visible only to those who guard their bodily eyes shut, so as to better see with the eyes of faith. Light in this painting is none other than the sweet light of divine grace—of faith, hope and love: fides, spes, caritas. Our remarks are confirmed by the painting’s first “Odescalchi” version, in which light is, this time around, that of law with respect to which Saul withdraws as a solder struck on the battlefield, suffering an agonizing pain—as if Paul had considered the factum brutum of the law, or law devoid of a transcendent dimension, as a lethal weapon.

But let us return to the first version of Saul’s Conversion, there where light is welcomed by Saul, that is Paul, as a lover embracing him in absolute intimacy. The conversion of Saul is none other than the marriage of Saul, the bachelor, to Christ as walk of life and logos, “truth that speaks” in Paul there where he shall declare that it is she who lives in him (Gal. 2.20). This truth who speaks “in Paul” is what Dante referred to as visibile parlare (Purg. 10.95), namely a discourse constituting the boundaries of experience, or the Alpha and Omega of the movement of things.

The logos does not speak about things, as a journalist would, for things themselves speak in it. Otherwise put, the logos is the discourse belonging to things, a discourse living at the heart of things and constitutes their very life.

The conversion of St. Paul with respect to his celibacy amounts, so to speak, to his marriage to the truth of the law, his transferal into the house, or rather the most intimate chamber of the law, there where the spirit or primordial impulse of law reveals itself as the absolute identity of man. Here, Paul discovers himself in the presence of the Second Adam behind the First Adam. A presence necessarily hidden to the servant still lingering in the dream of the man of humus, the son of the earth, who serves an unknown master, a master whose real identity he dares not seek. For the groom there is no light aside from the external one, the one of law conceived as imposition. So it is that the groom rests satisfied with his servile condition, which he has in common with beasts of burden. We find this servile condition represented also in the Calling of St. Matthew, where the three men-of-arms who detect the presence of the law consider it in effect as a menace, before which they defend themselves by retreating, or rather by letting the light reach out directly to Matthew, as if the law were there finally for him alone, and not for them. In effect, their activity, related to tax-collection and thus to money, is by no means forbidden by the law. Why, it is not Christ’s intention to condemn the men sitting at the table of power: neither they, nor Caesar, are targeted by divine law. Far from it, since Christ is focused on pointing to the consummate recipient of the law, namely he for the sake of whom the law is ultimately worthwhile being followed.

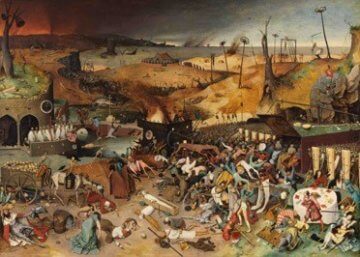

Caravaggio’s light evokes a lesson suggested by the biblical discussion between Abraham and his God over the fate of Sodom: the city would have no raison d’être aside from the community of those faithful to a law irreducible to power and offering us an indispensable point of reference in the fight against barbarism, that is against a life lived under the banner of thirst for (and concomitant fear of) power. A city ruled entirely by concern for the appearance of righteousness, as opposed to righteousness itself, or being righteous, is doomed.

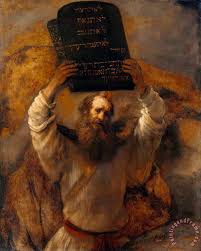

Now, insofar as our trust in the law cannot restrict itself to appearances, that is to the power of the law, we are called, especially as long as we reside among impious peoples, to interpret law, not only vis-à-vis its deep meaning, but also with respect to those who would want to reduce law to an instrument of power. In this latter respect, it is not enough to hide or run away from barbarians and their threats: we must face them, even proactively. We should then enter into the “spirit” of law, no longer resting satisfied with being nourished by law from without, or above. The piety of the children of Abraham is good in itself, but it clearly does not suffice there where we are challenged directly by the children of Dagon, coveters of power, or more concretely of the masks of our mortality. Thereupon, a novel defense of the law is called for, one that can succeed only to the extent that it takes its bearings from the innermost recesses of the law.

Confronted with the so-called pagan world, the Jew must transform himself or convert into a Christian in the sense that, for the sake of defending himself from an imitation of divine law, he must render explicit, as much as possible, the hiatus between the appearance of law, on the one hand, and the core or essence of law, on the other. It is here, in the proclamation of a veritable conflict between the Letter and the Spirit of the Law, that Christianity finds its birth. The conflict emerges in the context of a justification of divine law, or of the divinity of law, in the face of the challenge incarnated by the pagan imitation of divinity, which is to say of the pagan or “poetic” manner of relating to divinity. For the new Jew, or the Jew transformed into a Christian, the divine is the heart of the human, as mind is vis-à-vis flesh (for the flesh corresponds in us to what the Letter signifies with respect to law).

We are not dealing here with a new “subjectivity” of law, juxtaposed to an “objectivity” that had been previously proclaimed by the Hebrews of old. There is no question of admitting the modern psychologizing of authority. Far from it, since the first Christians announce the mystery of the objective (real) presence of the divine in the human, and then again not in the human conceived as “individual” (be this a Cartesian ego, or a Leibnitzian “windowless” monad), but in the human in its pagan or political conception, the human that we could call with good reason, republican: the political animal par excellence.

In sum, the Christian would be none other than a Jew who responds to the challenge posed by pagan politics to theocracy. The Christian justifies the Jew in the face of a “genetic” conception that the pagan has of human life. For, if for the pagan, man is humanized by poets out of a beastly state, according to the Jew humanity is rooted in God, so that his origin deserves being conceived, not in terms of a birth, but of a divine determination. Otherwise stated, the challenge before which the Christian-Jew finds himself consists in witnessing the properly divine root of all politics, including pagan politics.

Thus it is that the Christian exposes universally a coincidentia of nature and divinity at the heart of politics, the beginning of which—what in Hebrew is Bereshit—reveals itself as divine genesis. Now, that does not mean that the Christian abandons what we could call the “objectivity” of law, for it is precisely this objectivity that the Christian must defend. Yet, not being able to defend it after the manner of his Hebrew ancestors for whom the objectivity of the law had not yet been seriously called into question, the Christian will be de facto obliged to articulate a novel defense of law, at the risk of endangering the pietas of his own people. For, the Christian defense of politics is addressed to all peoples, without privileging any single one to the exclusion of others.

Who, then, is the recipient of the law the light of which Caravaggio shows us in his Calling of Saint Matthew? That law speaks to the most secretive intimacy of the human being, independently of his nationality. She speaks, in a word, to “the Roman,” to the citizen as such and thus to our civil nature. We are not brutes by nature (we do not emerge into this world from below it, but fall into it from above);[1] on the contrary, we are civil or political beings, begins desiring or seeking with all their heart their divine perfection, in a heroic civilizing act, an eminently ethical one represented notably by the great pagan authors of classical antiquity. The human being is an animal, which is to say a living being, who cares for the likes of him by reminding them of the divinity of our origins or common nature. Our humanity lies in caritas conceived and lived as primordial care directed towards what is divine in every man.

Ultimately, that is what the light of Caravaggio’s Calling really addresses. She calls man insofar as she seeks herself at the bottom of our soul, thereby vindicating a necessary or inalienable civil bond between law and nature, between the light that shines upon us and the light that hides within us.

The reestablishment or rather reactivation of the creative bond between visible and invisible light—in common artistic parlance, between the light and darkness of chiaroscuro—constitutes the hermeneutical mastery key allowing us to rise back to the soul of Caravaggio’s work, recognizing in our painter an exceptional heir of classical antiquity, rather than an accursed precursor of modernity. Even there where, in his Martyrdom of Saint Matthew (1600), light will illuminate tragedy in its most ancient and cruel character, threatening to tear apart once and for all every tie between the divine and the human, the rupture between Caravaggio and the sweetness proper of the Hellenism so praised by Matthew Arnold, is not definitive. On the contrary, in the painting worthy of being recognized as the most tragic of our civilization, Caravaggio awakens in us a pre-philosophical terror and, in doing so, he offers us an invaluable initiation to the original conditions—including a terrible conscience of injustice in its most brutal facticity—to the spiritual preconditions, then, of the birth of classical philosophy.

Figures

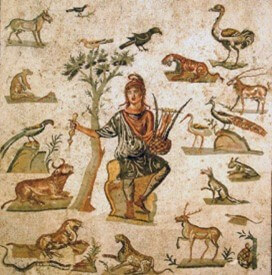

1. Caravaggio (Michelangelo Merisi), Conversion of St. Paul (second version), 1601; 2. Caravaggio, Calling of St. Matthew (1600); 3. Caravaggio, Conversion of Saul (“Odescalchi”), 1600; 4. Caravaggio, Conversion of Saint Paul, (detail); 5. Bruegel, The Triumph of Death, 1562; 6. Raffaello Sanzio, The Flight from Sodom (Logge, Vatican Palace), 1518-19; 7. Rembrandt van Rijn, Moses Breaking the Tables of the Law, 1659; 8. Anon., Orpheus Tames the Beasts (Roman Mosaic, Palermo), 3rd c. A.D.; 9. Michelangelo Buonarroti, Creation of Adam (Sistine Chapel Ceiling), c. 1511; 10. Caravaggio, Martyrdom of St. Matthew, 1601.

Notes

[1] The classical “fall” of man—whether biblical or Platonic-Plotinian—invites the thought that prior to being in his world as the character of a story, or a dream, man is somehow awake outside of his world. The Christian proclamation of a divine Second Adam hiding ab origine behind the First Adam (image of his God), suggests even more strikingly that the “first” or “absolute” Man/Adam (consummate dimension of the human) is not merely a created dreamer, but most importantly an uncreated persona eternally awake outside of any creation.