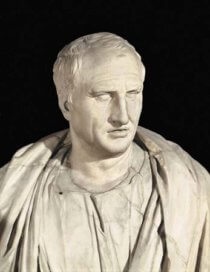

Cicero

Marcus Tullius Cicero (106-43 B.C.) was the Roman philosopher who erected the basic conceptual framework of the “law of nations” which has influenced subsequent international law, theory, and ethics. During Cicero’s time, the need for a universal code of ethics had become pressing, as Roman conquest had created a polyglot empire with an elite suffused with a wide variety of foreign philosophies and religions. Furthermore, the subjects of this new empire were neither Roman citizens who could partake in civic life nor were they the conquered slaves of despotism. Confronted by this challenge, Cicero revived Roman republican traditions under the guise of a statesman who would be limited to and accountable for his power by following a code of universal ethics embodied in the Stoic notion of natural law.

However, Cicero was not a Stoic but a skeptic: he believed that humans cannot be certain about their knowledge of the world and therefore no philosophy can ever claim to be true. Although skeptics did not offer constructive arguments of their own, they were able to see all sides of an issue and accept beliefs until a better argument presents itself. This is the path Cicero took as a lawyer and a philosopher but not as a politician, a role in which he turned to Stoicism and Peripatetic philosophies for guidance. Since as a skeptic he was free to accept any argument that he had found convincing, Cicero put forth Stoic doctrines to be followed provisionally by the Roman elite in order to improve both individual and collective life.

Cicero’s Stoicism postulated that the gods existed, loved human beings, and rewarded or punished them according to their conduct in life. But most importantly was the gods’ gift of reason to humans. Since humans have this in common with the gods, the most virtuous and divine life was to live a life according to reason. It was reason that enabled humans to discover and follow the natural law: the source of all properly-made laws for both individuals and communities. Because all humans shared reason and therefore could discover natural law, humanity could be conceived as a single community which followed this universal law. Thus, natural law created not only a singular community of humanity but it also provided a singular ethics.

Cicero made some of his most important pronouncements on this universal code of ethics in On Duties where he established the principle of war as the last resort to maintain peace. For Cicero, a state must first exhaust all options before choosing war in defense of itself. War should never be considered as a first option or for retributive justice. In fact, when a state was victorious, Cicero recommended that the state be generous in the sparing of lives of the defeated in order to promote peace and friendship among enemies. The promotion of peace without injustice was the underlying principle of Cicero’s thoughts on war and thereby defined not only the just causes of war but also placed limits on the conduct of war itself.

In peacetime Cicero also made significant contributions to global ethics with his ideas of hospitality and friendship, concepts that would be later adopted by thinkers like Derrida and Levinas. According to Cicero in On Duties, strangers were to be treated with hospitality, with nobody being injured for the sake of the betterment of somebody else. Such acts were contrary to nature, for, as members of a universal community, every human required equal respect and dignity. And since all humans demanded the same treatment, friendships that transcended region or race became possible. In On Friendship Cicero described the nature of true friendship as one between good and virtuous people who followed natural law. He offered advice of winning the glory of friendship through good will, honor, and liberality, the last virtue being particularly important as a form of aristocratic largesse to particular groups of the citizenry. Friendship therefore was not only the bond among the most virtuous but it was also the cement between classes in society (albeit this latter form of friendship was inferior to the most virtuous kind). Cicero’s notions of hospitality and friendship therefore could serve as the basis for a universal, cosmopolitan community.

However, the pressures of local attachments and the adversities of political life threaten the fabric of this cosmopolitan community. Recognizing that humans were more closely bounded and therefore obliged to their families and local communities rather than non-familial members and cosmopolitan citizens, Cicero proposed patriotism to overcome these familial and local attachments. Philosophy itself was an inadequate basis for a universal community because only a few could live the life of reason, whereas the many preferred the pursuit of pleasure. Thus, it was the task of the statesman to discover truth and convey this truth to a particular political community through suitable rhetoric in order to persuade people about the authority of the law. But this rhetoric also required philosophy, as Cicero argued in On the Republic and On the Laws; otherwise, the statesman would become tyrannical.

It is important to note that the cosmopolitan community did not abolish the attachment to particular communities for Cicero. Humans were attached to what specifically belonged to them as well to the universal good itself. Particular political communities were members of a universal cosmic order in the sense that its dictates – the precepts of practical reason – became law. The fact that a universal political community did not pragmatically exist was not a problem for Cicero, because every community to some extent followed the natural law in their human-made laws. Since individuals were part of a group of humans that shared human laws, each one was part of a political community and therefore had a duty to that community. This obligation was informed by the natural law that called for individuals to partake in politics, so far as it is possible, in order to improve the communities in which they live. That is, politics was informed by a universal code of ethics but was practiced in a particular community.

Cicero’s contribution to global justice were not only limited to his understanding of natural law but also included critical concepts like friendship and hospitality, limitations to the causes and conduct of war, and the institutionalization of these ideas into local and universal communities. Although the scope of justice for Cicero was universal, the application of it ultimately was local. Cicero’s Stoic vision of an eternal and immutable law for all nations, the virtues of friendship and hospitality, the principles of warfare, and the duty to serve one’s local community formed the conceptual framework for global issues that would subsequently affect international theory, politics, and justice.

Further Readings

Cicero (1913-2010) Works: Loeb Editions. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA

Dyck, R (1997) A Commentary on Cicero, De Officiis (On Duty). University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor, MA

MacKendrick, P (1989) The Philosophical Books of Cicero. St. Martin’s Press, New York

Nussbaum M (1994) The Therapy of Desire Theory and Practice in Hellenistic Ethics. Princeton University Press, Princeton

Pangle T (1999) Justice Among Nations. University of Press Kansas, Lawrence, Kansas

Powell, J (1999) Cicero the Philosopher: Twelve Papers. Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK

Wood, N (1988) Cicero’s Social and Political Thought. University of California Press, Berkeley, CA

This essay was originally published with the same title in Deen Chatterjee, ed., Encyclopedia of Global Justice (Springer Publishing, 2011), 129-30.