David Hume’s Inadequate Examination of Miracles and the Limitation of Thought

“One moment even of feeble contrition or blurred thankfulness will, at least in some degree, head us off from the abyss of abstraction. It is Reason herself which teaches us not to rely on Reason only in this matter. For Reason knows that she cannot work without materials.” – C.S. Lewis, Miracles

When one ponders the field of philosophy and the point of pursuing it, the individual finds himself posing various questions. Often these can take shape as quite meaningful and deep queries into fundamental aspects of reality. The open-minded may be drawn to the notion that if a maxim or some proposed mode of operation has made you think, then that thing is worth thinking about. The same general rule is applicable to the asking of questions.

If it is something which can be asked, even if easily avoidable, should it not be asked to exhaust all possibilities of error? Perhaps this question itself deserves examination prior to its being asked in the first place. Nevertheless, asking questions is what philosophers do; they are thinkers. They suggest questions, even questions which they personally have no answers to. However, one philosopher, in particular, rose up in the 18th century who believed much of the work, much of the thinking, of the predecessors in his field was simply foolish. He would be one to find great fault with the acts of the Greek Fathers and would view thinking about a First Cause to be a terribly nonsensical waste of time. This determined man was David Hume.

Hume specialized in tackling topics regarding the very processes of thinking and of knowing. The pinnacle of his contribution to philosophy can be summed up in the thesis: all ideas are copies of impressions – impressions being defined ad mental experiences, such as those induced by the senses, and ideas being mere memories of impressions, notions reflective of past experiences. This cornerstone thesis has since been widely accepted as the key to empiricism.

In his discourse on philosophy and thinking in general, Hume stated that he saw the old school abstruse philosophy as a pointless, meaningless endeavor. In Hume’s philosophy, if an answer to a question can not be given, then the question itself is empty. More than that, such a question should never be asked at all (despite the perplexing notion that one might not know whether there is an answer or not if the question never gets asked). It seems Hume wants to shut down certain ways of thinking. Here, Hume shows some slight resemblance to René Descartes’ train of thought. Hume thinks certain questions do not deserve to be asked; in a sense, it seems, he feels them simply don’t deserve an answer – even if there could be one. And Descartes, stating that sources which were wrong in one thing cannot be trusted in anything else, wants to silence the voices of certain thinkers and their bodies of work. It sounds like both philosophers were seeking to put different limitations on the scope of philosophy.

As for Descartes, who was of the idea that a source of information, a thinker for instance, was rotten to the core if but one of their ideologies was disproven. If Descartes’ limitation was embraced, it is quite likely that the fields of thinking and learning would be the worse for it. They would be stunted, and many people would become perpetually silenced Galileos, they and their work disregarded, nullified by mere preference.

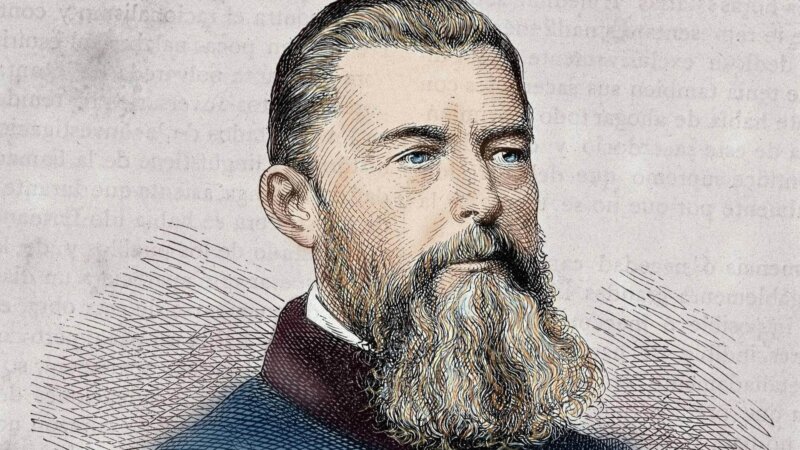

Take, for instance, a specimen of astronomical studies – Percival Lowell. Here was a man who lived a fulfilling life with contributions to the pursuits of science, politics, and literature. Among these contributions was the belief that there had to be some unseen celestial body in orbit beyond Neptune. He employed those at his observatory to commence a quest for this mysterious planet. It was not until 14 years after Lowell’s death, however, that their energies proved fruitful with the discovery of Pluto.

Despite his spot-on assertion in one aspect of astronomy, Lowell had a doomed liaison with another. During the turn of the century, he became utterly engrossed in the idea that there were canals on the surface of Mars and that furthermore, they were the work of intelligent minds. Unfortunately for Lowell’s reputation, this theory has long fallen out of the circles of serious scientific discourse. In Descartes’ eyes, this would likely be grounds for the dismissal of everything Lowell said and did. And yet Lowell already proved himself to be a brilliant astronomer with another one of his theories which was accurate. In other words, the ideals of Descartes would limit the outreach of the theories of such a scientist, who made a genuine contribution to his area of study.

Healthy skepticism is something to be admired, but overlooking details that might be important is by no means an honorable attribute. Hume does something few rational people would: widely criticize and ignore both faith and science. As an empiricist, he denies even thinking of the existence of God or of a personal soul. One could see it simply follow that the man would be overly skeptical when it came to discerning those supposed acts attributed to the supernatural.

Holding another mindset of limitation, Hume strongly disliked miracles. His primary examples for miracles were those Christian-based events which he would have believed to be twisted myths at their best or fairy tales at the worst. He sees miracles as fundamentally necessary to Christianity, and he was quite right in this view as the total fulfillment and most ecstatic moment of Christianity came in the miracle of Christ’s Resurrection.

But Hume’s further and deeper comprehension of a miracle’s definition is not entirely accurate, at least by Christendom’s understanding of such an incident. He would believe that Christians see miracles as being probable when, in fact, most perceive these to be rare, unlikely, and improbable. Hence they are supernatural, above the natural order of things.

Miracles, in the Judeo-Christian sense, might be defined as those anomalies existing within creation that make baffling boundaries out of natural laws, boundaries that do not confine or constrict their Creator who is above them. They are wonderfully strange and unexpected. A man who was as dead as a doornail spontaneously coming back to life is certainly a miraculous feat to boast. It sounds remarkable, unbelievable. Here, in seeing that Hume’s own view of a miracle was flawed, if one wanted to just be a real Descartes about it, he would dismiss Hume and all of his philosophy.

However, I believe that this manner of learning is quite flawed itself. An idea that has made you think about it is worth thinking about. And any question, regardless of whether or not it can be answered, deserves to be asked. Overlooking David Hume’s mishap on a miracle’s definition by those whom he sees as needing it so badly, we should look at how impressions, or rather the lack thereof, factors into Hume’s understanding of experience and knowledge. There are two chief manners in which knowledge is traditionally approached in philosophy: through a rational process (a priori) or through thoughts rooted in past experiences (a posteriori).

Hume believed some ideas were based on something other than reason, preferring the a posteriori method of coming to knowledge. (For Plato, sensory experiences and rational principles worked hand-in-hand. He covered both his bases this way.) Anyway, whether rationalism or empiricism is employed, Hume would doubtlessly still argue that ideas are rooted in prior impressions. Now, within the philosophical realm, I pose this question: If a miracle is an impossibility (more specifically an “impossibility” which did not occur), then where did the notion of it come from? In other words, how was the idea of a miracle fabricated with there being no previous, grounded impressions on which it could be based? How does a natural being come up with a supernatural idea of a supernatural event?

Furthermore, where did the notion of God and the capacity for miracles originate? How did it come to be? Since the beginning of recorded history, archaeological data suggests the majority of people had methods of worshiping supposed deities. In the realm of empiricism, if God cannot be factored into existence, then there should exist no impressions of such a Being. There ought not to be impressions of miracles, yet there are. Even Descartes, who had some slight influence over Hume’s work, would conclude that an individual human being could not concoct the notion of God without some external suggestion.

Rather than answering these questions, Hume dismisses them and shies away from them, claiming they are not worth his time. He’s dodging a bullet that might do harm to his thesis. He does not want these questions being asked; he does not want people looking into certain affairs. Hume’s philosophy, in practice, puts a constraint on certain modes of thinking. Hume isn’t searching for an expansion of views or even of knowledge. Some horizons should not be sought after; one should simply not strive to answer certain difficult, important questions.

The mathematician should just drop what she’s doing in the midst of searching for a response to an as-yet unsolved equation. After all, if an answer seems to be far from readily available, it should not be asked in the first place. If Hume had tweaked his work or spent some time really pondering the questions above, he would come to some fair conclusions. But what makes his stance more absurd than certain aspects already are is that he had the capability to delve into deeper questions regarding the First Cause and what some may call the supernatural, and he deliberately chose to ignore these inquiries.