Debating a Determinist: A Philosopher and Blogger Dialogue on Determinism, Free Will, and Philosophy

The thesis of determinism is one of the strangest theories promoted by many academic philosophers. Many determinists seem to think that they can assert the absence of free will in human life and that our conception of human existence can go on as before with little else changed. However, the implications are so profound and far-reaching that the “life goes on just as before” idea seems comparable to imagining a community remaining unaffected by a nuclear bomb going off.

A blogger calling himself “Robot Philosopher” offered to challenge some of my assertions from my essay The Determinist Strikes Back. This seemed like an opportunity to see just how a determinist would respond to what seems like truisms. It all ended rather badly. Recently, people friendly to me have pointed out that RP is an obvious dogmatic troll and should have been avoided. With hindsight, I am sure they are correct. But the interaction, together with reading Iain McGilchrist’s The Matter With Things, has given me additional insight into both my own thinking and thinking in general. RP was an excellent example of the mode of thought to which McGilchrist has devoted his massive two volume masterpiece to counteracting. The left hemisphere fantasist is indistinguishable from a dogmatic troll anyway! One would think that Daniel Dennet and co. were kidding, but apparently not. It is truly the best they can do.

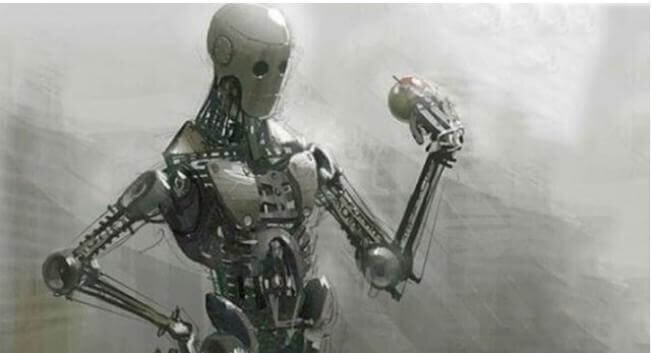

All bullet-pointed comments are mine. The unbullet-pointed are RP’s. RP’s very first paragraph below sums up his extremely disparaging view of what it is to be a human being; as compulsive robots following their programming. On the one hand, responding to someone with such an inadequate picture of humanity might seem pointless. On the other hand, his description is consistent with the actual nihilistic implications of determinism; a view held by tenured professors of supposedly reputable disciplines like physics. So, looking at that consequence squarely in the face seems helpful.

To be upfront about my own view, determinism is fundamentally the denial of consciousness and, thus, agency. Materialism implies that all that is real is physical, and it is materialism that drives determinism. Obviously, if only the physical is real, then the mental world is unreal. At most, it is an anomalous byproduct of physical forces and it, most assuredly, cannot turn around and affect physical reality in the manner of top-down causation. Thus, materialism is already the denial of agency and consciousness. Never mind that the placebo effect, for instance, provides an example of top-down causation – although many scientists did their best to ignore it until the evidence simply became overwhelming. Materialism is a form of reductionism – reducing human beings to their physical elements. As such, materialists have tended to want to find ways of describing human behavior without reference to mind, such as behaviorism, or to introduce the most minimalist “explanations” of human behavior possible, such as psychological hedonism. Thomas Hobbes, a mechanist, trying to mimic physics, reduced everything human to attraction and repulsion. Nuance was not his strong point. Any normally functioning person would do better. Unfortunately, being very wrong and thus outrageous is intrinsically interesting and can seem “new” and “original;” two things admired in the age of individualism.

Interesting philosophy has an ethical component. I am interested in defending the self-conception of mankind from the slander that is materialism and determinism. So, this negative behavior of attacking determinism, is motivated by a desire to defend the good, the true, and the beautiful. The little line-following robots described below, held to represent what it is to be a human being, are clearly none of those things.

“If determinism is true, there is no “you” to have preferences or not. Only agents have preferences.”

Says who? Human action, at its foundation, is no different than one of those small robots programmed to point its camera at the floor and follow the black line where it leads. Humans are simply much more complicated and have much more programming – the choices we make generally are much more complex – but we follow the same sequence when determining our course. When the robot makes a “choice” to veer left to follow the line, it has done nothing but reference its programming and equations and variables to their inevitable conclusions. Humans do nothing except reference our programming (genetic, chemical, societal, etc) in order to come to also inevitable conclusions (at least, in the conscious decisions which you would claim we “freely” make).

[Robot Philosopher had claimed that there is nothing nihilistic about such a view.]

RP pretty much makes all my points and then some in his first paragraph. There is not much more to say. Utter nihilism. According to RP, human beings are little robots following black lines on the floor. He literally writes that we are “no different” from that. We make no choices. What appears to be choices is “nothing but” our programming. Little robots following black lines do not have “preferences.” They do what they are told. If it made any sense to refer to “preferences,” it would be the preferences of their programmers. But, it will turn out, RP puts great stock in the notion of preferences to support determinism.

Following black lines on the floor is an example of the tightly rule-bound environments A.I. requires. Hence, A.I.’s ability in terms of games like chess or Go. A machine can be defined as a rule-following device. “Tightly rule-bound” is not, however, the environment of living organisms. There are no algorithms, for instance, for a successful marriage. (Heuristics, perhaps).

Iain McGilchrist calls what RP is doing the philosophy of “nothing butterism.” “Humans are nothing but…”

The line “humans are only more complicated” does not get us anywhere. RP has no evidence for any of that and it is a radically inadequate way of characterizing human consciousness and behavior. See “The Chinese Room Thought Experiment by John Searle.”

From the article:

“Sometimes I bring to class a plastic doll called the “Yes Man.” When turned on and tapped on the head, the Yes Man utters pre-recorded statements that all signify agreement. “When you’re right, you’re right.” “I couldn’t agree with you more completely.” “Say, I wish I’d thought of that.” “I’m sure whatever you’re thinking is correct.” The doll is manufactured as a parody of an ingratiating employee of a company hoping to get ahead by being agreeable and making his boss feel good. I bring it to class as a rebuttal of the computer theory of mind – the idea that human beings are mindless, algorithm-following automatons, i.e., machines. This is not what we are like is the intended implication.

Once I showed it to a fellow professor, explaining why I used it in class, and the person said “But that is what people are like; only more complicated.”

This person had once confessed to me that in a whole class of people practicing techniques used in Rogerian counseling where one “mirrors” the meaning and emotional component of what someone has just said to you, (“I’m upset that my boss doesn’t understand me” is met by “Not being understood can feel frustrating”) she had been the worst at figuring out what other people were feeling or what emotions they were expressing verbally. This lack seems likely to have contributed to her imagining that we human beings are just more complicated versions of the Yes Man.

The Yes Man is literally mechanical. He is not conscious. He understands nothing. His ability to speak English exists only because an actual English-speaker had his voice recorded, someone else stuck it on a chip and someone else again put it inside the doll. This woman was telling me that this is what it is like to be her. She, apparently, experiences herself to be just like the Yes Man but with a wider repertoire of pre-recorded responses. The implication is that she is not capable of thought, understanding or feeling. She experiences herself as a mindless automaton – a plastic toy from a joke shop.”

If we humans are just bags of circuits, or whatever mechanical description RP wants to give us, then it makes no sense to talk about “you,” only “it.” There is a bunch of circuits in the corner. OK. So what? Well, there is another bunch of circuits called a computer. OK. Now there is another bunch of circuits. I’m going to call that bunch of circuits by the pronoun “you.” Why? No reason at all! Well. I’m not going to go along with that. The first bunch is an “its.” The second bunch is an “its.” And the third bunch is an “its.” Hence, there is no “you” if determinism is true. Anything RP might say against that stance is arguing FOR my position. He would have to say, “Oh, no. We are much more than a bunch of circuits following their programming and we absolutely deserve the second-person personal pronoun.” The further we get from the human, the less justification there is for using the pronoun “you.”

RP will later call this line of argument, “subjective semantics.” However, I am just trying to point out the atomic bomb-like implications of determinism. If taken as true, life simply cannot go on as before. We do not use second-person personal pronouns for computers. If human beings are identical to computers, then we should try to be consistent.

In reading Iain McGilchrist, in particular The Matter With Things, and in responding to RP, it is becoming even clearer to me that good philosophy (and mathematics, physics, etc.) usually starts with a Gestalt: an intuitively perceived whole. In this case, what it is like to be a human being. The right hemisphere provides the material for analysis. The left hemisphere then analyses it, if necessary. The results can then be fed back to the RH. Moments of deep insight in philosophy, science, and mathematics appear at once, generally after extended periods of reflection. Proof, if needed, comes after the fact. Novices proceed by sequential reasoning. Experts, when successful, see the solution and usually are unable to say how they did it. Normally, the insight is not the result of a step-by-step reasoning. RP posits an absolutely ugly and inaccurate description of human consciousness and existence. It might be a fairly accurate description of aspects of the LH but the RH intuition, imagination, creativity, humor, metaphor, and feelings are all missing. RP literally describes us as more complicated versions of little line following robots following their programming. In later interactions, RP got progressively more incensed that I refused to attribute agency to this conception of human beings. He literally describes an entirely imaginary scenario where human beings clearly lack agency, and then insists we are agential. In order to pull off this sleight of hand, he has to radically denature the notion of “agency,” which means to act as the center of decision-making and not to be the mere passive recipient of social or physical forces. If what you do simply reflects and is the result of those forces, then you do not have agency by definition. Agency is the ability to choose what action to take.[1]

As far as I am concerned, RP’s initial description of what it is to be a human being is so flagrantly wrong, laughable, and inadequate that there are several possibilities. One is that he has got a theory in his head (LH) and if it contradicts every single aspect of his own experience and his experience of other people, too bad for experience! Another possibility is that he is autistic or schizophrenic and is not capable of feeling and intuiting the reality of either himself or other people. Analytic philosophy, like much of the rest of the modern world, does a good job of mimicking these two mental pathologies, so that may be it as well. A feeling of unjustified certainty and thus dogmatism is also characteristic of the LH.

Kant’s transcendental argument operates in reverse. One starts with the experience and then infers what else might be true for that to be possible. In Kant’s case, it was the experience of moral responsibility implying metaphysical freedom. Kant’s method avoids dogmatic LH theory.

I am pretty sure, from what he wrote later, that this appeal to intuition and feeling RP despises. He frequently refers to “appeals to emotion” as a fallacy. Two things can be said about that. One is that some aspects of the world cannot be correctly perceived without emotion. To watch as an innocent person got kicked in the head until his brains spilled out and he died, and not to be horrified, would mean that you had not appreciated what you were watching. It is not simply the heartless, “Person X can now be presumed to be deceased,” but a truly horrible event involving extreme brutality. Cordwainer Smith’s Do Scanners Live in Vain? (reviewed here) captures the way in which feelings must frequently be included in moral decision making in order to make the right choices in a brilliant piece of philosophical science fiction. Schizophrenics and autistic people whose LH feature too largely in their thinking tend strongly towards means/ends, consequentialist trains of (im)moral thought. The Scanners have been mechanically separated from their feelings and must look at gauges on their chests to see that they are not getting overly excited. If they ignore the gauges too much, they can accidentally kill themselves by overloading. Secondly, the determinism/free will debate centers around the nature of human existence. The nature of human experience cannot be fully explicated or defined. It is “known,” not in the sense of a series of abstract propositions, but in the sense of familiarity. English, annoyingly, just conflates “knowing” someone with knowing a fact; even knowing how. Some aspects of human experience are amenable to scientific description, while most of it is not. In many respects, schizophrenics and autistic people do not know what it is like to be a normal human being and they are very aware of this fact. Instead of just intuiting how to behave socially, or what someone is feeling, they have to try to construct rules and schemas which, of course, do not work. If RP is missing this RH intuitive, felt understanding of being human, then all my attempts to point it out he just finds frustrating. I would seem to be pointing at a void. It is quite likely that he has been taught that good thinkers should ignore all that vague, undefined stuff. One of his most common complaints about interacting with me is that I am being evasive, or not answering the question. From my point of view, it is a bit like a kid asking, “What does ‘cute’ mean?” And I point at a baby or a kitten and say, “An adorable quality that appeals to parental and protective feelings and makes you want to stroke it, hold it, or otherwise interact with it.” And the kid says, “I don’t know what you are talking about. I feel none of those things.” If the kid were Jeffrey Dahmer instead, he might be inclined to stake it out in the forest and watch it die from dehydration or sunstroke in the mode of “an experiment.” If that Gestalt intuitively understood comprehension of being human is missing, no argument can take its place.

Is this once again an “appeal to emotion?” The argument is that emotion can serve a cognitive function and that in some contexts epistemological accuracy is unobtainable without the requisite feelings. Why mention Dahmer? Because RP’s vision of human beings as little line following robots with no free will is supremely dehumanizing. No matter how complicated a little line following robot gets, it does not suddenly gain moral status as something not to be harmed. RP’s vision of human beings is perfectly consistent with Dahmer’s willingness to perform “experiments” on living creatures in the forest, which was his prelude to murder and cannibalism. Again, if this seems histrionic and emotive, ideas have consequences. And conceptions of human beings have consequences. The accuracy of the “little robot” description has direct bearing on whether determinism is believable and true. To dehumanize is to encourage human experimentation and also consequentialist moral reasoning, which is in fact typical of the left hemisphere. Hemispheres can be magnetically suppressed in real time. The same person can be asked a moral question with his LH functioning, and no RH, and vice versa. We know, experimentally, that LH is consequentialist, and RH, deontologist. LH treats things as inanimate. The RH alone deals with the animate; actual living creatures.

It is not rational to appeal only to rationality, narrowly conceived. Such people cannot be trusted.

Let’s try one more thought experiment. Imagine you are an alien. RP gives you his description of human beings as complicated robots following their programming and then he leaves. When he returns, he finds you pulling people’s entrails out of their stomach, and measuring how loud they scream when you do that. Could he blame you for thinking such behavior would be morally alright?

The determinism RP is describing implies human existence has no more worth than line following robots. There are emotionally horrifying consequences to such a point of view. By ruling out “appeals to emotion” it is as though RP wishes us to actually argue in the manner of a robot, which would help to make his point. If the topic is, for instance, nuclear warfare, or concentration camps, failing to introduce emotionally-informed moral notions into the argument would be inappropriate. Determinism, with its denial of agency and thus meaning, is a moral and epistemological disaster for our understanding of human beings.

None of that programming can we honestly say we had a choice in how to interpret/perceive and therefore any outcome was likewise not freely chosen. In that sense, robots show the exact same amount of “agency” over what they do. ie: they follow their programming and nothing more. Would you agree?

I would not agree that humans and robots have the same degree of the scare quoted “agency.” Following programming provides no agency of any kind. (Later, for some reason, RP strongly objected to my claim that determinism involves a denial of agency.)

It would not be wise to be too flippant about the use of the word “programming” here. We know that computers/robots are programmed by human beings. We know they do not have free will. They are tools used by human being for human beings. To the extent “will” or purpose is involved, it is the external will of the programmers. Human beings do not have human programmers who literally write code that must be followed. If it were conceded that human beings have programming in the same sense as robots then it is game over and we can all go home. The ways in which humans might or might not be like robots is exactly the point of debate.

One way that people who think that artificial general intelligence (AGI) will be attainable, and RP thinks it attainable, is by talking human intelligence down. The more they can convince us that humans are machines, the more plausible it might seem that a machine could replicate what humans do.

Recently in a podcast, a geneticist commented about genes that generally they give people a disposition to do something. In this case, it was a tendency to put on weight. This is not determinism. The geneticist actually has this gene himself and is only somewhat overweight. He has to make an extra effort not to eat too much. He did not lose his free will as a result.

We have no evidence that “interpreting/perceiving” are wholly genetically determined. So, no. I will not concede that. IQ is 0.8 in heritable. The Big Five Personality Traits are 0.5 inheritable. These will push us in various directions, limit us in some ways, contribute to our strengths and weaknesses, but we have no evidence that they abrogate free will. Having free will does not mean being entirely free of external or internal influence. Belonging to a culture provides concepts, traditions, and habits that influence thinking and behavior too. It is not possible to spell out all the ways they do this either.

Iain McGilchrist is both a psychiatrist and a philosopher. His main interest is right and left hemisphere functional differences. Schizophrenics and sufferers from autism do not have the lateralization that other humans have, namely, a well-differentiated role for the right and left hemisphere. The right hemisphere is the one that is in charge of well-functioning, normal human beings. The RH is responsible for Gestalts, our sense of living organisms, emotions, time as flow, intuition, and it connects us with reality rather than theories, concepts, and maps. The left hemisphere (LH) is merely there for logic, reason, and representations of the lived world, useful for manipulating the world and directly related to the right hand with which we primarily do this. Delusional people, psychiatrists tell us, typically suffer from an excess of reason, not a deficiency. They are often perfectly logical, but, operating from faulty assumptions and an inadequate connection to reality, they draw the wrong conclusions. For people where the RH is not dominant, they have a sense that other people, and themselves, are not real: that, in fact, they are robots or actors playing a part. Everything seems to be merely a simulation. This is literally how schizophrenic people experience the world. So, the “we are all robots” people resemble those suffering from a mental disorder. Analytic philosophy, neurologists, and many others are often strangely similar to these dysfunctional individuals. Some of them are actually autistic. I had one such colleague. His facial expression never changed; a telltale sign. Regarding free will, he said, “I cannot imagine how free will would be possible.” This indicates that his belief, in this regard, was the result of his limited imagination. And also, the supremely hubristic idea that if he could not understand or imagine something, it must be wrong. By that criterion, the existence of life and consciousness would have to be ruled out of existence as well; never mind dark matter.

“and your beliefs and preferences are irrelevant have no effect on anything.”

I see I was correct that you think the ultimate end of determinism must be nihilism.

This, I believe, is patently untrue and it ignores entirely my argument I made previously.[2] It doesn’t matter that I didn’t choose to possess the belief that I want a good life.

The nihilism of determinism is as clear to me as any philosophical topic I have ever considered. It is patently untrue that it is patently untrue. The nihilism of determinism is one of those intuitive Gestalts I was referring to. (Admittedly, intuitions can be wrong, and they still need proving or defending.)

If I am not master of my destiny to at least some small extent, or even how I feel about my destiny, then what is the point? This will come up in later stages of the argument, but according to RP’s worldview, one does not even get to choose how one responds to events, let alone cause any of them.

For determinists, everything is a matter of duress. To anthropomorphize determinism for a second, it as though someone were to put a gun to my head and command, “Eat your dinner.” And tell me, “Then say,” ‘Yum. That was nice.’ “Now say,” ‘So, Honey, how was your day?’ Etc. That would be an absolute nightmare. But it gets worse. This person, it turns out, is an evil genius and somehow has the power to determine everything I say, think, and feel, and to make me feel like I have chosen every action, feeling, and reaction. He has, for instance, decided that I will love some woman who is utterly horrible, physically and mentally. How would I know? I cannot think for myself. Perhaps he is laughing at how deranged my choices are, the words I speak, and the things I feel.

The man says, and this is straight out of a bad movie, not only will you do what I say, you will think you want it; even enjoy it.

And THEN he tells me, I will now reveal that you can take neither credit nor discredit for anything you have ever created, imagined, written, said, eaten, or anything else. And, by the way, creativity and imagination do not exist. Those are just meaningless words we give to actions and thoughts and they have no metaphysical reality. (This could be illegitimate mind reading my part, but RP never mentions such things as key aspects of being a human being and they do not seem consistent with determinism.)

RP then has the gall to say that this existential nightmare is not nihilistic. I can imagine a kind of “ignorance is bliss” situation under this imaginary scenario, but, once I am convinced that it is real, then immediate suicide would seem a good idea. At least such a fool would no longer be the pawn of purely physical forces and his meaningless life would have some meaning in his death.

Dostoevsky imagined such a reaction in Notes From Underground. The underground man says near the end, to paraphrase: “If I am no more than a piano key that someone else is playing and psychological hedonism, an iron law, says I must always act in what I think is my self-interest, then I will deliberately do something self-sabotaging and self-destructive just to assert my own independence and freedom.”

RP says: “It doesn’t matter if I did not choose to possess the belief that I want a good life.” However, there is no meaningful “you” under determinism to choose anything. For a determinist, everything is a sequence of events put in place by the Big Bang, perhaps occasionally interrupted by purely random quantum events, according to his own metaphysical beliefs.

What on earth would “a good life” mean for a mindless automaton with no free will? Or, if it has a mind, a mind that is trapped within the automaton with no ability to alter a single thing about its life?

Whether your life is “good” or not is completely random and meaningless for a determinist. Physical forces have forced you think your life is supposedly “good” or supposedly “bad.” None of that has any meaning. It would just be the luck of the draw. Pure happenstance. On top of that, deterministic forces could persuade you that being a member of the Waffen SS, or the Bolsheviks, was absolutely the pinnacle of human existence.

A good life? It is not even your criterion of “good” or not.

Under determinism, I have no choice about how I argue, or what I do, and neither does RP. Neither he nor I are “persuaded” by reasons. Persuasion is an illusion, for determinists. So, this whole exchange would be meaningless: merely compulsive behavior with no more significance than the outbursts of someone with Tourette’s Syndrome.

What does “you” are “worried” mean in this context anyway? Automatons are neither “you” nor meaningfully “worried.” The illogicality of determinists is one of the most abhorrent and repulsive aspects of determinism. As a fan of logic, properly applied, I admit I find this distressing.

Yet I have that preference.

There is no “I.” “You” are bunch of circuits. You are an it.

“Preferences” are irrelevant. Who gave you those preferences? Under determinism, you are a slave, a mechanism, and a nullity. “Its” do not have meaningful preferences. You cannot act on those preferences, since only agents act. You, unfortunately, are caught up in a meaningless charade.

If I make good choices – regardless of whether I freely chose them – my life will be more pleasant to experience.

Under determinism, there is no “you,” and there are no “choices,” good or otherwise. In the quotation at the beginning of this article, RP has made it clear that he thinks choice is a pure illusion. It does not exist! One merely does what one is programmed to do by genes and environment. He cannot simply reintroduce choice again when it suits him.

Whether what this programming does is good or not is not something we can evaluate, under determinism. Our thoughts on the matter are predetermined by something else that is not us. We do not get to make our minds up on any topic, including philosophical ones.

The word “if” there, “If I make good choices,” is interesting. “If” is a hypothetical and counterfactual. It implies that genuinely alternative courses of action are possible, and thus free will, whereby you would not be a merely mechanical mechanism following its programming.

Or, “if” could be merely a “for argument’s sake” tactic. Perhaps, “if we pretend that choice exists for a second…here is what would follow.” But this “if” would imply the ability to choose how I argue, defeating the argument.

And if you make bad choices, your life will suck. You have no choice either way. You are simply a passive observer sitting on the sidelines waiting to see what fate has decided for you. You are part of a sequence of events no different in kind from any other physical chain of cause and effect.

“My life will be more pleasant to experience.” In what sense is it “my life?” Its life?

So, you have “preferences.” What does that even mean in this context? Who cares? Does a computer have “preferences?” No. According to RP’s description, he and we are a computer. Nothing more.

*Whether or not my choices are free, I can still perceive experiences as good or bad.*

What exactly is “experience?” That would require consciousness and an “I.”

Something else is determining whether you experience something as good or bad. There is not much point in having an opinion about it. The opinion is not your own anyway. You have no choice in the matter. Since experience implies consciousness, and thus agency, then the concept is out of place in this discussion.

At this point in the argument, RP is describing a horror show. He admits that, according to his thesis, he has no control over anything. Events are simply happening. He cannot change them. He cannot change even how he reacts to them. He chuckles, he cries, he moans. The Big Bang determined what you would do 13.5 billion years ago, or some quantum event introduced a new causal stream. At most he is a puppet. A marionette with someone else pulling the strings. “Your” “preferences” are a joke.

The notion of “preference” introduces a mental item into a purely physicalist schema and, like “experience,” does not really belong in this discussion.

In this mixed-up way of thinking, “you” are somehow conscious, but trapped. “You” have “experiences,” whatever those are, since they have not been scientifically defined, and you think some are “good” and some “bad.” But, someone/something decided that for you. And the whole thing is utterly subjective, which does not seem a good look for a materialist determinist.

Perhaps “bad” is really “good.” Who knows?

I think that’s what you’re ignoring. And convincing others has an effect, regardless of whether either of us can fairly claim responsibility for such effect.

There is no “convincing” if determinism is true. There are merely sequences of events. You move that way. I move this way. You feel X. I feel Y. There is no real conscious human there to convince in the first place. And there is no “you” doing any convincing, nor can you convince a bunch of circuits. There is neither covincer, nor convincee.

Only conscious beings can be “convinced.”

In his reply, Robot Philosopher will say that I have captured his idea of “convince” perfectly and thus how can I deny that any “convincing” is going on in determinism? As you have seen, I have just explained. If all is cause and effect, “convince” as a category of mind means nothing. “Convincing” someone for him is just to alter someone’s programming and even doing that implies agency outlawed by determinism. Actual computer programmers would never talk about “convincing” a computer by changing a line of its software.

For the determinist, “to convince” is not different in kind from kicking someone in the shin or any other physical alteration. RP agrees. If all is physical cause producing an effect, the effect becomes the cause of a new effect, and so on, and everything is really just this, then there is no way to distinguish “preferences,” from “convincing” or any other item that belongs to a mental category.

If every time you ask to pull back the curtain, and there is the same old physical cause and effect standing there then it behooves RP not to introduce distinctions without a difference into the debate.

RP wrote: “When the robot makes a “choice” to veer left to follow the line, it has done nothing but reference its programming and equations and variables to their inevitable conclusions.”

There are no “preferences,” “convincing,” “good” or “bad” in this scenario.

RP needs to face the consequences of his own line of reasoning.

I’ve never heard that before – that we cannot have preferences if true.

Obviously, you cannot take credit for or claim ownership of a preference assigned by someone, or something, else. In determinism we could be compared with imaginary figures in a computer game. Someone else is determining everything. We might pretend that the figure “wants” to rescue the princess and “hopes” she does not die, but really it is the person playing the game. All those preferences were assigned and are not “your” preferences in any meaningful sense.

The difficulty with the analogy is that preferences seem inextricably linked with consciousness. Lawn mowers, computers, and other inanimate objects do not have “preferences.” The difference between us and figures in computer games is that we are conscious and I think we intuitively understand that conscious creatures are responsible for their actions and choices, and thus have free will. Creatures have minds of their own. So, if I really want you to do what I want you to do, better to keep you unconscious.

Once “preferences” are introduced, effectively, you are introducing consciousness and consciousness implies free will and moral responsibility, as a matter of experience.

Since preferences and consciousness are so intertwined, it is a way of having your cake and eating it too. The free will advocate says, “Yes. I have preferences. Now you are talking about humans again, not little line following robots that clearly do not have “preferences.”

Talk of “preferences” confuses people because it seems you are conceding something you are not. As Thomas F. Bertonneau said, “Determinism is the denial of consciousness.” Better to stick to the one paragraph argument for determinism. Everything has a cause. Everything is physical (bringing in the denial of consciousness). Given the cause, the effect is in some way “necessary.” Hence, since your brain is physical and generates consciousness (not proven – we only know the two are correlated), then you “must” do whatever it is that you do, think, and feel.

Nothing in determinism necessitates that end or even hints at it.

A computer can be programmed to attempt to convince people of things too, and I’m assuming we’d both agree that computers do not yet have consciousness.

Computers cannot “attempt” anything. That is an anthropomorphic or at least animistic word borrowed from the language, metaphysics, and ontology of agency. That is intentional language involving goals. Later you will say that computers argue. If you say that “to argue” means exactly the same thing for computers as it does for human beings, then human beings do not argue either and you cannot make your point. If you are found actually arguing with your computer, and not merely shouting at it in frustration, then you are in danger of being taken off to an insane asylum.

With a computer, there is no one there to be convinced.

Nobody can be convinced of anything if free will does not exist. “You” can cause “me” to alter my programming, but “you” are not actually “doing” anything and neither am “I.” A sequence of events has occurred. End of story.

And yet I’m also assuming we’d both agree that computers are nothing but causally determined physics in motion, yes?

Yes. Computers are causally determined physics in motion. Fortunately, capable of being programmed by us.

And as far as I know, most determinists (including myself) don’t necessarily believe everything that happened since the big bang was causally necessary, as quantum physics seems to have credibly shown that there is true randomness within reality.

Randomness is a problem for physical determinists. It does not contribute to agency. Some sequences of events are random (let’s say). And some are determined.

But determinism is comfortably maintained without Laplace’s Demon. I think that confusion is mostly semantics, based on far outdated theories of determinism.

The best definition I’ve yet found on determinism (and I believe most popular, as it’s #1 on Google) is “the doctrine that all events, including human action, are ultimately determined by causes regarded as external to the will.”

That is fine with me.

Laplace’s Demon is an imaginary omniscient being who, given the location, speed, etc., of every atom in the universe, and a knowledge of the laws of classical physics, could accurately predict everything that would happen from that moment on.

As long as we have no choice over what our preferences are, free will is impossible in my view, and 100% of our preferences are governed by that which is out of our control.

To address the second part first, I have no idea how you would prove that 100% of our preferences are governed by that which is outside our control except to simply assume that determinism is true, which you are supposed to be proving.

Just as there is the mystery of consciousness, perhaps it would be accurate to say there is the mystery of preference. We do not know where either originate.

Scott Adams uses the phrase, “Getting someone to think past the sale.” For instance, the question, “Who is the best tennis player to have ever lived?” To begin arguing is to assume that there is some way to determine that. The real question is, “Is there any way to determine who in history is the best tennis player?” So, we need to examine the key terms first.

RP uses two terms in his statement that “we have no choice what our preferences are.” Choice and preference. It is a strange claim because determinists believe that we have no choice about anything, so “preferences” are the least of it. I do not choose the books on my shelf, the TV shows I watch, the food I eat, the friends I make, my occupation under determinism. I have no agency at all. When we tell black people that they are doomed because society is racist, we are denying them agency. We are saying there is absolutely no way to make your life better because of the thoughts and behavior of white people. There are forces outside your control stopping you from altering your fate in society. In particular, any chance of success is non-existent. Of course, the existence of successful black people contradicts this, but never mind!

Is a “preference” supposed to be a physical item or a mental item? Normally, it is mental. In normal English usage, a mere “preference” is a fairly flimsy thing. “What kind of coffee do you like?” “Well, I prefer Guatemalan.” “Will you drink Columbian?” “Sure! That’s good, too.” We do not normally think of it as doing much heavy lifting. If someone were at a party and someone said, “Would you prefer it if every person here was actually a famous movie star from the past? You could talk to Humphrey Bogart, make jokes with Mel Brooks, and ask Mel Blanc to do cartoon voices.” You say, “Sure. Too bad most of them are dead.” In that case, it would be a mere counterfactual preference.

If “preference” is a mental item, a vagary about the way our minds work, then for it to be significant for a determinist, the determinist would have to accept top-down causation. A mental event would have to be capable of causing a physical event, but dualism sidesteps physical determinism based, as it is, on the laws of physics. Yet, if we return “preference” to the physical realm, which is surely the place where a materialist determinist should wish to be, it has no particular meaning. It would be, at most, a vague mental feeling of some kind, that is irrelevant to causal chains that determine my behavior. Cause/effect, cause/effect, cause/effect (ooh, look that one feels like a preference), cause/effect.

Are they “my” preferences if determinism is true? Since the possessive makes no sense in that context, these “preferences” are just more deterministic entities in the universe. “You” and “I” as conscious agents are just obliterated and reduced to part of the sequence of events.

Counterfactually, if preferences were determined, for argument’s sake, I am still free not to follow my preferences. Sometimes we do what we prefer and sometimes we do not. That is normal English usage. If you claim that whatever it is that I actually do reveals my “real” preference, then you are committing the No True Scotsman fallacy, as argued in my article: The Metaphysical Status of Preferences. If even hypothetical exceptions are outlawed, then one is engaging in tautologies, and playing with words, rather than making statements about the world. Real statements about the world admit of counterfactual exceptions. The statement “the sun is 9000,000 miles from the Earth” would be false if in fact the sun were only 8000,000 miles away. So, “the sun is 9000,000 miles from the Earth” is a genuine factual statement about reality. In order to show that we do always follow our preferences in real life, RP would have to give a hypothetical example of not following our preferences. He cannot. Thus, he commits the No True Scotsman fallacy. “Bachelors are unmarried men” is not a fact about the world, but a fact about the meaning of the word “bachelor.” It is true by definition.

At a later point, RP will say that “we always follow our preferences” is true as an axiom. This is confusing. Axioms are supposed to be self-evidently true. They cannot be proven. Since I have already established that there is no reason to think that we always follow our preferences, it is clearly not self-evident. How would a mental item come to have such force that it must always be obeyed, overriding physical causation? A determinist should stick to physical cause and effect. That is where he is strongest, in which case “preferences” come out in the wash. I am pretty sure that RP thinks that whatever one in fact does reveals one’s REAL preference which has the same logical flaw that no REAL Scotsman would do such and such, when that is clearly what has just happened, so you just make it true by definition that no real Scotsman would do that.

“A man can do as he wills, but he cannot will as he wills.” Schopenhauer.

So long as what I do will is the product of my creativity, imagination, sense of humor, mood at the time, character, life experience, genetic and environmental influences, cultural and social factors that constrain my range of choice, interests, love of art, film, philosophy, friends, and family, dislike of nihilism, I do not think that if it is true that I cannot will what I will bothers me. Schopenhauer seems to be introducing the idea as a kind of paradox. I do not think he was arguing for physical (physics driven) determinism. I am unclear what to “will as you will” would actually mean. And I think that is part of Schopenhauer’s point. One interpretation of Schopenhauer’s line, found at random is, “you can choose what you want, but your wants are chosen for you.” That interpretation introduces a mysterious chooser of your wants. Can he choose what he wants you to want? Obviously, this is too anthropomorphic. There is no chooser. We are back to the denial consciousness that determinism implied from the beginning.

Both free will and determinism are unprovable postulates. Arguing for determinism involves unavoidable performative contradictions that necessarily suspend adherence to the metaphysics the determinist is postulating while arguing for the determinist position.

If one is arguing compulsively as the result of mindless physical forces then this throws my ability to think out the window. An argument is supposed to be a means of persuading someone via reasons, not physical causes, and reasons need to follow their own rules of logic, not physics. If you say physics engages in syllogistic logic, then you are imagining a physics with the properties of mind, and have entered into the realm of idealism, and thus physical determinism is off the table again. If determinism were true, I, by definition, would have no choice about whether I am on the side of free will or determinism. I would have no choice whether I find an argument compelling or not, and the person I am arguing with is also the victim of physical chains of causation.

Arguing for free will involves no such contradictions. Metaphysically, free will will require appeal to some nonphysical spiritual reality and thus faith. Faith in free will is thus faith in God. It is faith in real meaningful consciousness and thus agency. It is faith that life has meaning and that other people are perfectly real and not merely computerized simulations following complicated programming. This seems consistent with my experience of myself and others. Free will, like consciousness, cannot be fully explained or explicated. There are lots of things like that. We are unable to provide the necessary and sufficient conditions for knowledge, but knowledge exists anyway and denying that it does also involves a contradiction, namely, knowing knowledge does not exist. Gödel’s theorem proves that not all true things can be proved. This is true of both axioms and Gödelian propositions. We think we do not know what 96% of the matter in the universe is made of and just accept these limits on our ability to know.

In the act of creation, we take something from the unknown and drag it into the known; the light of day. We do not know what we will discover or create until we have created it. There is no algorithm for creativity and if there were, then it would not be creative. Creativity and discovery are predicated on the limits of the known. Free will must exist for creativity to exist. Line following robots are not creative.

Interestingly, the brilliant movie The Iron Giant is about existential choice and free will. The Iron Giant is a robot who has been designed by aliens as a giant weapon. Unlike real robots, the Iron Giant is conscious. He is damaged landing on Earth and temporarily forgets his “true” nature. He befriends a little boy, Hogarth, who protects him. The robot can transform into a gun, but it only does so when attacked. The trouble is, the more he responds violently the more he gets attacked. Near the end of the movie, seeing that otherwise the robot will be destroyed, Hogarth places himself directly in the line of fire and tells the robot that he does not have to be a gun. “Guns kill. It’s bad to kill. And you don’t have to be a gun. You are what you choose to be. You choose!” He says. Earlier in the movie, the robot sees a deer only for it to be shot and killed. Hogarth explains that it has been killed by hunters with guns. Thus, the robot is taught what death is, and also what “gun” means in English. And repeats the phrase, “Guns kill.” As a presentiment of what is to come later, when the robot sees the gun he briefly starts to transform into his own gun-like form, but, since he is not directly under attack, Hogarth manages to snap him out of it. Later in the junkyard, Hogarth explains that it is bad to kill, but not to die. The Iron Giants asks if he will die. Hogarth replies: “I don’t know. You’re made of metal but you have feelings and you think about things and that means you have a soul. And souls don’t die.” “Soul?” Asks the Giant. “Mom says it is something inside all good things and that it goes on forever and ever.” The Iron Giant repeats to himself, “Souls don’t die.” The director of the movie had a sister killed by her husband using a gun, and he wanted to make a movie where the potential killer chose not to “be a gun” whatever his nature might incline him to do.