Out of the Crooked Wood: How Eric Voegelin Read Immanuel Kant

To start with the premise that the philosopher is entirely free–the governing assumption of . . . all analytic philosophy–might only end with the assertion that what he can teach us is infinitely less than what political life requires. Conversely, to be bound to a history of ideas . . . might liberate thought and politics from the negative and dissolving conclusions of analytic philosophy.

—Eldon Eisenach, Two Worlds of Liberalism

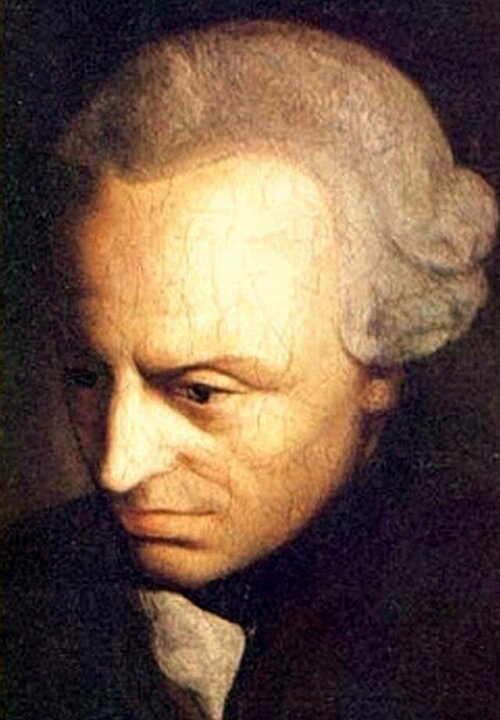

In this article we will consider Eric Voegelin’s response to Immanuel Kant, the magisterial Prussian philosopher of the late eighteenth century. The questions that serve as the bases for interpreting Voegelin’s reception of any particular modern philosopher, such as Kant, would be those that are important to both:

- The nature and order of reality,

- The epistemological challenges of modernity, and

- Plausible social and political arrangements we might hope for in the modern world.

Our general approach is to explore how Voegelin’s own work of understanding human experience in a philosophically adequate way might have been helped by his sympathetic reading of certain modern philosophers. This approach seems especially plausible because, as Jürgen Gebhardt argues, Voegelin “was consistently engaged in a critical discourse with the great thinkers who struggled with the enormous task of making modern man understand himself.”1

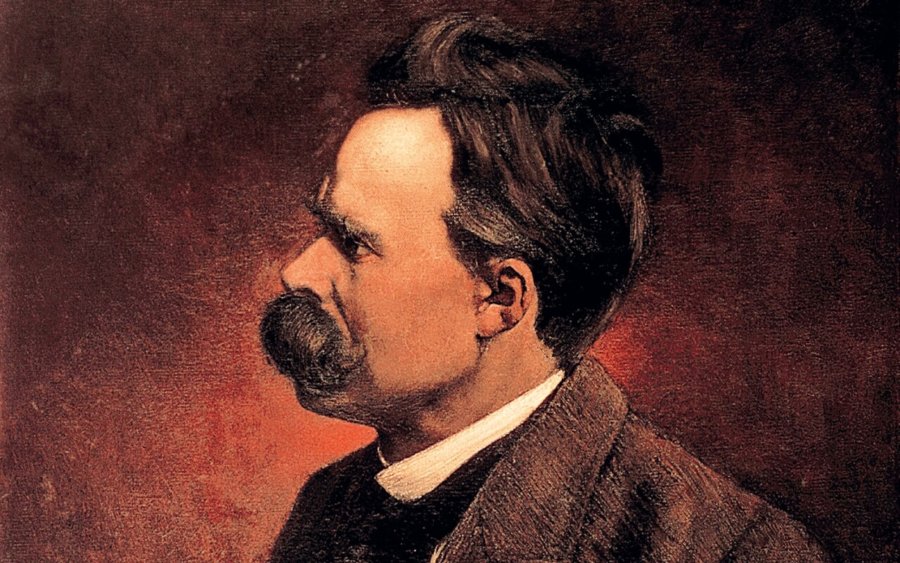

Although Gebhardt lists “Hegel, Schelling, Nietzsche, Heidegger, William James, and [Alfred North] Whitehead” in that line of great thinkers, he curiously enough does not mention Immanuel Kant, the philosopher who, “appear[ing] in the guise of a universal pulverizer . . . initiates the era of scientific philosophy so that everything that preceded him declines by comparison to the level of relatively irrelevant metaphysics.” On the other hand, Gebhardt does include Kant in a similar list of “outstanding political philosophers” (quoting Voegelin) in an introductory comment a decade later.2

Gebhardt is a competent and careful interpreter of Voegelin’s work: his two different placements of Kant’s work in Voegelin’s opus is an observant reflection of Voegelin’s own ambiguity. For example, Kant’s new mode of philosophy is, according to Voegelin in 1928, a “brilliant development” that “with Hegel . . . abruptly breaks off.” Forty-nine years later, however, his remarks concerning Kant seemed more dismissive. In Voegelin’s essay, “Remembrance of Things Past,” he recollected concerning his rejection of Marburg neo-Kantian influences, among many other “schools,” that overcoming their “formidable force” took considerable time and effort.2A

This project of overcoming might lead one to think that Kant’s philosophy was subsequently of little concern to him.3 Similarly, a recently published anecdote from Ernest Walters concerning Voegelin’s unwillingness to teach Kant’s philosophy seems to vitiate any attempt to construct either a conversation between Voegelin and Kant or to develop an understanding of any Kantian “influence” on Voegelin:

“One day at LSU, I was standing in the hallway, and I ran into Voegelin. I then asked him if he was going to take up Immanuel Kant. He said, well, he hadn’t thought about that. Then he asked, “Why do you want me to?” I said, “Well, I know nothing about Kant and the German idealists.” Voegelin said, “That’s where I started, and I spent my entire life trying to extricate myself from those idealists.” And I thought about it today when we were talking about freedom: Voegelin once said in class that the greatest writing on freedom was Schelling’s essay on human freedom. So, for quite some time, I wondered if Voegelin had really extricated himself from Kant and from the sort of teachings that came after Hegel and Schelling. But I thought that was rather revealing, that he would have said something like that to me.”4

The most casual perusal of Voegelin’s works indicates that accepting the dismissive orientation to the question of Kant’s influence implied in this story would be a mistake. Voegelin’s “extrication” would itself be worthy of a careful look, but in pursuing the question, we will find ourselves better off if we take a different route, discovering more than a story of escape.

An Unsystematic Conversation with Kant

Apart from one early essay and several episodes in the two books on European racism, Voegelin did not again engage in a systematic published consideration of Kant’s thought. To find more of his thinking, we will undertake a survey of the various remarks he made and his limited encounters with Kant during sixty years of philosophical inquiry. His explicit criticisms of Kant’s philosophizing as well as his approbations must, therefore, be gathered up as acorns in the harvest.

One also observes that Voegelin’s thinking may itself in identifiable ways be a tribute to Kant. Are there traces of Kantian influence or Kantian formation to be found in Voegelin’s work? Does he share with Kant a common vocabulary, a common set of reference points, a common set of problems? If so, what are they and why? If not, what does that lack of coincidence tell us? What are the contexts of Voegelin’s explicit and implicit departures from Kant? Where, and in what ways, do we find him specifically parting ways with Kant?

Such an approach suggests, a priori, that Voegelin will have treated Kant and his philosophical inquiry not primarily as an object of investigation, in the way he treats Marx, but as a participant in a (philosophical) conversation.5 That assumption will itself require verification, and we will indeed discover a certain degree of ambiguity at times.

In the preface to the final volume of Order and History, published posthumously and uncompleted, Lissy Voegelin states that Voegelin “knew very well [that the pages of this his final work were] the key to all his other works and that in these pages he has gone as far as he could go in analysis, saying what he wanted to say as clearly as it possibly could be said.” Kant is regarded in these final pages as the first in a line of German philosophers who took up the task of recovering “the experiential basis of consciousness,” which required the removal of “layers of propositional incrustations accumulated through the centuries of thinking in the intentionalist subject-object mode.”6

His “scientific philosophy” was burdened in this regard with “the habit of thinking in terms of thing-reality,” a habit whose traditional legitimacy was further strengthened by the “success of the natural sciences” in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.7 This success may have induced Kant to treat Newtonian physics “as the model of ‘experience'” in his Critique of Pure Reason, so that breaking out of the subject-object mode of thinking about consciousness, which Kant affirmed, was made that much more difficult.8 Thus:

“in order to denote the ‘more’ than physics that is to be found in ‘Reason,’ he could do no better than to coin the symbol Ding-an-sich. Since the internal confusion of the famous symbol is not sufficiently realized even today, as far as I can see, it will not be improper to stress that “in-itself” the thing is not a “thing” but the structure of the It-reality in consciousness. The technical problems engendered by the symbol, however, are not the present concern; rather, the symbol’s character as a symptom of the pressures that let the attempt to recover the experiences move existential consciousness into the position of a “thing” must be explored.”9

This final extant remark concerning Kant sets our stage for a further retrospective consideration.

On the one hand, Kant’s genius uncovers or rediscovers the elemental problems of philosophy, in this case the problem of thinking of consciousness exclusively (and illegitimately) in a purely intentionalist, subject-object mode. On the other hand, that genius is held short of a complete breakthrough by the limitations of the philosophical-terminological context within which it operates. The most important of these, to which we will return, is the subject-object mode of acquiring knowledge in the natural sciences as the only mode of human experience or source of knowledge.10

Voegelin’s evaluation of Kant’s work reminds us of his critique of the work of Max Weber in The New Science of Politics Praising Weber for the breadth and depth of his scientific studies, Voegelin argues at the same time that Weber’s commitment to positivism imposed shortcomings, because it strictly limited what he could achieve theoretically. Weber’s work marks the final outcome of positivism, but sensing a horizon beyond positivism, Weber himself, like the biblical Moses, “knew what he wanted, but could not break through to it,” so that he “saw the promised land but was not permitted to enter it.” Because it rejects the metaphysical elaborations of classical Greek and medieval Christian civilization, Weber’s science remains incomplete, but it points us in the direction we must take to fulfill Weber’s scientific promise.”

In the same way, his final remarks concerning Kant shed all the light necessary on Voegelin’s dismissal of the “schools” in his recollection of overcoming neo-Kantianism in the Marburg style. Whatever Kant may have achieved philosophically, the dogmatic encrustations of neo-Kantian “schools” such as the one at Marburg subordinated those achievements to doctrinal constructions.12 Thus, Voegelin could explain in 1966 that it was already clear to him while beginning his philosophical work in the 1920s that “the poor state of political science–through its being mired in neo-Kantian theories of knowledge, value-relating methods, historicism, descriptive institutionalism, and ideological speculations on history–could be overcome only by a new philosophy of consciousness.”13 The danger of leaving philosophy behind in favor of default epistemological and historiographical constructions is already present in Kant’s system building: Kant’s philosophical setting seemed itself to become a limitation to his philosophical work.

“Ought” and Human Freedom: Intimations of a Philosophical Anthropology

Voegelin’s first and only systematic treatment of Kant’s work in its own right occurred in a 1931 essay, “Das Sollen im System Kants,” by which time he had already come to realize the limits of the political science of his time. Despite the remarkable interpretive-analytical prowess he displayed in his analysis of Kant, Voegelin’s interest was not “philological,” not in understanding Kant’s thought for its own sake, per se, but for the sake of untangling a philosophical knot. It was a forensic and ironic exercise in extrication in which Kant played a double function.

The essay was published in a Festschrift for Hans Kelsen,14 Voegelin’s doctoral supervisor at the University of Vienna, a famous advisor in the drafting of the Austrian Constitution of 1920, and the leading proponent of the positivist “pure theory of law.”15 The basic argument of the theory’s advocates was that legal theory should not concern itself with “the phenomenon of law in the context of the totality of our experience of the state.” In other words, the experiential basis of law–the experience of obligation or “ought” [Sollen] (or, in less Enlightenment-bound language, the problem of justice, namely, who owes what to whom)–was not to be a consideration in or an element of legal theory. Rather, “the task of the legal scholar consists in establishing and interpreting the relevant legal statements, connecting the statements into a system, and subsuming cases into it.”

For the reasons already noted, Voegelin had come to consider this approach inadequate, if one was interested in understanding the phenomenon of what he then called “the state,” and would later come to call–less parochially–political order or social order. Voegelin’s examination of Kant’s ethics was one in a series of studies and published articles that were moving toward the same goal: to develop a political science (Staatslehre) that offered a more thorough account of the roots of political community and organization than the prevailing positivist legal theory in the line of Kelsen.16 Such a project would require, among other things:

“the development of a philosophy of human beings and their actions that would also include the problems in intellectual history of the jurist. We therefore return to Kant, because we find in his work a clear view of the essence of a human being, and because we hope that in examining his ideas concerning the moral law and ought, we will expose the topography of a problem area that is independent of his time and person. In this way it may even be possible to lay the groundwork for a theory of ought that is a desideratum of contemporary legal theory.”

The purpose of this specific study, then, was not so much to understand and absorb the specific substance of Kant’s system, but to fashion by means of Kant’s questions a “reorientation” out of the context into which the problem of political order had been set, or misstated, or hidden in positivist theory of law. Voegelin proposed “to study the topic of this problem area in the work of a thinker who possessed a total view of human being.” For this project to “bear fruit,” Voegelin would have to “extract from the peculiarly Kantian ideas the problematic that is relevant to us.”17

This procedure is not, to be sure, an especially unconventional use of a philosopher’s work, but it is one that requires a careful reading at three separate levels of analysis. First, what did the philosopher say? Second, what was he trying to do? Here we find a common location for interpretive missteps, since, as Voegelin shows in his reading of Kant, this intention is frequently not clearly indicated. Third, what do the statement and the intention mean for us?

In the Prolegomena to Any Future Metaphysics Which Will Be Able to Come Forth as Science, a kind of synopsis of his Critique of Pure Reason, Kant famously stated that recollecting Hume’s arguments concerning the impossibility of linking cause and effect a priori in our reason awakened him from his “dogmatic slumber.”18 This awakening is often taken to be epistemological. Thus Leslie Newbiggin writes:

“A [Cartesian] skepticism about whether our senses give us access to reality is in the background of the major philosophical thinker ever since. In the thought of Kant . . . the real or noumenal world must remain forever impenetrable by our senses. We can only know what appears to our senses, the phenomenal world. And the orderly structure which enables us to grasp and deal with the phenomenal world is not inherent in it; it is provided by our minds which, for the necessities of our own reason, provide the rational structure by which we can make sense of the phenomena. The rational structure [of the world is furnished] by the necessities of human thought.”19

Although this view of Kant as a philosopher seeking to establish the precise limits of human knowing is not incorrect (Kant’s review of the Critique in his Prolegomena, for example, hints at nothing more), Voegelin argues that it is–surprisingly–too limited. Using Kant’s epistemological delimitations as their starting point, legal positivists denied the relevance of obligation to a comprehensive legal theory by separating empirical from normative concerns in a manner they believed to be directly derived from Kant’s critiques. Voegelin, on the other hand, argued that he found in Kant’s chief “epistemological” works, including the first Critique, a “deeply stirring awareness of the spontaneity of action and of moral necessity,” which moved the Critique of Pure Reason beyond epistemological concerns to an effort “to provide a foundation for practical freedom.”

As John von Heyking and I have pointed out elsewhere, Voegelin’s argument concerning Kant’s “obsession with the this-worldly spontaneity of human action and its obligatory law” and his argument that Kant’s “investigation concerning the origin of the phenomenal world” in the first Critique “was developed and pressed only as far as was needed to gain a foundation for the doctrines of freedom of the human as a rational being and of the experience of ought” hint at a deep irony.20

Voegelin left this irony understated, but it cannot have escaped his legal positivist readers: a social science based on neo-Kantian epistemological principles, best exemplified in the sociology of Max Weber and the legal theories of Hans Kelsen, had endeavored to eliminate from consideration precisely such questions of freedom and moral obligation that seem to have animated Kant. A political science based on such an excision would also eliminate from view the experiential basis of any political community, namely, the human experiences of moral, intellectual, spiritual, and physical existence.21

An Anti-Positivist Reading of Kant

Voegelin amassed considerable evidence for his antipositivist reading of Kant. First, the concepts of spontaneity and “the-thing-in-itself” both exhibit a decided “vagueness” in Kant’s argument. Voegelin moves the reader through a careful and persuasive exegesis to show that–appearances notwithstanding–Kant was ultimately interested in a precise philosophical anthropology, and not merely an epistemological argument:

“The full implications of these extensive preparations become clear only when Kant takes the final step and identifies a human being, as a thing in itself, with the rational personality that is revealed by the experience of spontaneity . . . . Through this identification, the critique of knowledge is radically transformed into an ontology of the real [Realontologie] . . . . In the course of the terminological shifts that we have just indicated, the epistemological relational character is now suppressed by another, entirely different meaning of the noumenon that is revealed to us in the experience of spontaneity that illuminates existence.”

“It is now no longer a matter of understanding how objects are present to a perceiving consciousness [as in the ‘epistemological’ interpretations of Kant], but rather how human existence is structured and how its structures are revealed to us.”22

According to Voegelin, “The goal to which Kant’s investigation strives [is] transcendental freedom.”23 This goal is equivalent to the development of a philosophical anthropology that–taking into account the experience of obligation or “ought”–must underlie any theory of the state or political order. The concept of “ought” (and its underlying experience) is central to this effort:

“For Kant, ought is not a random philosophical topic beside others, but the one phenomenon of our existence that aroused him so profoundly that his entire philosophizing welled up from the ground of this arousal. The identification of the rational personality and its freedom with the thing in itself is not to be understood as an incidental diversion from the main lines of the investigation or as the derailment of an epistemologist; rather, the application of basic epistemological concepts to the problems of ethics is the essential goal to which the theory of ideas in the Critique of Pure Reason is consciously directed.”24

Kant’s goal directly implies a theory of politics. “The very introduction of the term idea sketches the ideal of the state [Staat] for which the theory of ideas is to serve as the systematic foundation (and which first occurs in the ethical writings).” Such an ideal has “practical significance” for Kant, “because the primordial image of a true state can lead the empirical, legal constitution of human beings to ever-higher degrees of perfection and thereby approach the idea of infinite progress.”

This idea of perfection, unfortunately, is based not on empirical observation–real-world examples of human behavior made Kant skeptical and even pessimistic–but on the model of an “anonymous man,” a human being who is neither “a concrete individual” nor a “typical individual person,” but ultimately “a species of humanity, of the metaphysical unit of all human beings.”25 Kant’s move to an abstraction presents problems as well as opportunities. On the positive side, Voegelin points out and criticizes several times the “terminological shifts and equations” by means of which Kant achieves:

“a cosmos of concepts for which all meanings blend into all the rest: A human being is an I, and an I is the same as the Thou and the same as humanity to the extent that all, as reason, are ends; my reason is the same as your reason and the same as human reason, humanity also exists as an end; individual reason is intelligible in contrast to individual sensuousness, and since reason is the same as the thing in itself and, further, since phenomenal things are given in the context of the world of experience, all are things in themselves, which are, in turn, the same as individual rational personalities, and these, connected within a world in itself, are the same as the mundus intelligibilis.”26

I refer to this as the “positive” side of the matter, because these muddying moves open up for Kant a space of freedom, a space in which to recover the “essence of the human being” and free agency, in contrast to the constrictions and near determinism or moral indeterminism that Kant found in Humean and other rationalist Enlightenment constructs.

On the other hand, while Kant reminds us of the experience of obligation or obligatory action, which has a “core of compulsion,” he unsatisfactorily “surrounds [this experience) . . . with the constructs of a philosophy of reason.” Parsing away the elements of this construct, we are left with an “authentic self.” The “experience of compulsion” that is legitimately attributed to this self (minus Kant’s further construction) would, in contrast to Kant’s rationalizing system, “have to be investigated in the broader context of a description of conscience, regret, and experiences of guilt.”

So, while Kant recovers certain essential experiences of human existence, he leaves aside a great many others essential to a full philosophical anthropology that would serve as the beginning point of a theory of politics. Nevertheless, the “extraordinary poverty of Kant’s image of man and society”–to which we will return–” . . . leaves several important contents” in its wake, whereby Kant fashions a system in which “we . . . find . . . a preliminary sketch of the investigations that would have to be undertaken in order to justify the concepts of a claim and a duty.”

Kant frames for us the basic human experiences and their attendant conceptual problems with which a science of politics must begin. Similarly, in the distinction between hypothetical and categorical imperatives, “Kant touches upon a fundamental problem of ought, one whose implications are certainly much more extensive than is evident in his thought.”27 These implications can be elaborated in a more adequate science of politics that pays greater attention to those features of human existence that Kant abstracts out of his system. Kant’s effort to establish a law of reason as such without regard for “heteronymous” content reminds us of the need to account for “those traits of human beings” with which all legal orders must concern themselves. These traits pose certain substantive, and not merely formal, problems.

Kant serves as a teacher whose system cannot and need not be taken at face value for him to play a liberating, pedagogical role for a postpositivist political science. In the context of a pure theory of law, this teaching role becomes ironic. That role, moreover, is not to be uncovered in a cataloging of Kant’s insufficiencies; rather, it attains its functioning power when the reader attends to Kant’s core philosophical-anthropological concerns, regardless of the unsatisfactory constructs erected around them. At the same time, the deficiencies of Kant’s philosophical project themselves serve as a pedagogical device: Voegelin’s critique leads us to a theoretically more fully adequate science of politics.28

If Kant intended to be a teacher, it was surely not in this manner. His stated intent was to rescue the possibility of a coherent metaphysics from Humean skepticism on the basis of a careful systematization of and solution to the problem of metaphysics.29 Kant was a philosopher working out a problem, not a post hoc liberator from doctrinal restrictions. In his reading of Kant, however, Voegelin is scarcely interested in Kant’s philosophical “system,” in doctrinal matters of deontology or its meta-ethical alternatives, or in metaphysical doctrines more generally. In this way, at least, Voegelin seems by 1932 to have “escaped” the “schools” of the German academy. He had no interest in “categorizing” Kant into any “school”: indeed, he showed no interest in deciphering Kant’s system beyond recognizing the severe limitations of such a form of philosophizing and deploying its usable elements, its motivations, and its failures for his own philosophical work.

Kant in the Race Books

In 1933 Voegelin published two studies of European race thinking: Race and State and The History of the Race Idea.30 In 1950 Hannah Arendt named them the best works available on the topic, and Voegelin regarded the latter in 1973 as among his “better efforts.”31 Oddly enough, however, they arose as side steps in the same project for which the 1931 Kant essay had been a “preliminary study,” namely, the development of a full political science [Staatslehre] “on the basis of a philosophical anthropology.” The entire study of the race idea thus “grew out of [Voegelin’s] work on a system of ‘theory of the state’ [Staatslehre],” wherein a “section on the various ideas about the state” was also to contain a presumably brief discussion of “body ideas.”32

These 422 pages (in the English editions) of analysis of race ideas therefore began as a subsection of Voegelin’s much larger project. Race and State presents the idea of race as one in a class of political-intellectual formations or “ideas”—namely, body ideas [Leibideen]— that are among the intellectual-imaginative elements that produce political communities.33 The History of the Race Idea presents what is essentially a genealogy of the race idea in European intellectual history. Voegelin’s work on body ideas began to “lead to a serious quantitative disproportion among the parts of the system,” because it had become evident, as he had already intimated in the essay on Kant’s “ought,” that “the roots of the state must be sought in the nature of man,” and an investigation of that problem tended toward expansiveness.

Insofar as Kant’s philosophical investigations added material to the modern investigation of the nature of man, they are important to any understanding of the modern idea of the state, just as Kant’s examination of “the moral experience of the individual” had given this experience one of its formal modern castings in the form of his systematic “ought.” (Voegelin would again observe decades later that the categories and vocabulary of Christian Wolff and Immanuel Kant—for better and for ill—dominated German intellectual thoughtways until at least the mid-twentieth century.)34

Kant appears extensively in these two volumes, the last time that he will do so in Voegelin’s work. With Kant, as with other thinkers whose work he brings to hand, Voegelin’s method is clear: “We have not ‘adopted’ theses from these thinkers, but have used their ideas to illustrate the problem and its speculative range in order to get a basic understanding of what is meant by these things; the problems in this area are not to be ‘solved’; they need to be shown first of all and to be restored to their importance.”35

To examine Voegelin’s interpretation of Kant in the race books is to study Voegelin’s placement of Kant in the genealogy of race ideas or, put differently, to study his “use” of Kant’s work to elucidate problems in a theory of the state in light of body ideas generally. The Race Idea does not examine Kant’s thought or provide an interpretation of Kant’s thought in anything but the most restricted sense. In fact Kant’s Critique of Judgment plays the leading role: in part 2 (“Critique of the Teleological Judgment”),36 Kant examines the problem of judgment concerning knowledge of the phenomena of the natural sciences and the kinds of teleological imputations we tend to make to such phenomena.

The race idea— namely, that certain characteristics of an individual human being can be attributed to his or her membership of a specifically identifiable genotypic (and hence phenotypic) group—is closely associated with the biological sciences. Human beings are seen as members of a biological series (species), which series is to one degree or another determinative for the physical, intellectual, cultural, and spiritual characteristics of any of its members. The specific mechanisms of this determination and the precise meanings of “belonging,” “series,” “species,” and “heredity” are given in the biological sciences. Any given idea of race must, to be remotely credible, have some connection to the findings of those sciences and the contemporary state of theory in them.

Kant’s philosophical analysis of scientific judgment, of the biological nature of the human individual, of the nature of the biological series, and of the phenomenon of life and our scientific access to it are therefore important both philosophically and as part of intellectual history. The nature of the race idea means that a genealogical analysis of it must engage several distinct, disparate, yet interrelated topics of biological, anthropological, sociological, politological, and literary inquiry.

As Voegelin wrote in a 1940 essay, some seven years after the race books:

“The body, that, as an idea, contributes to constructing the community, is not the body of biology; it is not an animal body, but always a body of the mind. The idea of this body may be pictured in objective animal ideas, but it can never coincide with them and may stray very far indeed from this image.”37

“This multilevel quality of body ideas (of which race ideas are a subset) is the reason for the multiple disciplinary incursions in any analysis of it.”38

In the space of fifteen introductory pages in Race Idea, Kant occupies four leading roles concerning a quadrangle of philosophical problems or developments in European intellectual history of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

Kant’s Rejection of Christianity

First, he is a central transition figure in the move from Christian body ideas—which Voegelin finds exemplified in the body ideas of Thomas à Kempis. For à Kempis, “the world is vain, and the body a prison,” so that the visible, the material, the “bodily” is of little consequence or value. It is that which is beyond earthly, bodily existence for which we should strive. In Kant’s philosophical anthropology, fundamental Christian experiences of divine transcendence of the kind à Kempis portrays are treated skeptically, and new basic experiences of bodily existence receive a more open, yet similarly skeptical, reception.

Kant’s system—once again—confuses: “As is characteristic for such transition times, we find in Kant experiences blending into each other that should be basic experiences, but for Kant they are no longer that or not yet that.” On the one hand:

“the undervaluing of earthly existence has remained from the Christian image of man—Kant considers it astonishing that philosophers could ever have come up with the idea that so imperfect and transitory a creature as man could ever fulfill the meaning of his life in his earthly existence and not need the hope of a life after death to perfect his faculties.”

And on the other hand:

“the Christian idea of the coming of the kingdom of perfected man is envisioned as attainable on earth in an unending historical process; on the infinitely distant temporal horizon the kingdom evolved on earth and the one effected by God come together.”39

Here we encounter for the first time a problem that Kant engages without resolution, to which Voegelin will refer frequently in his philosophical work after these volumes, and to which we will return: human alienation in the face of immanent progress toward a perfect future. This alienation is directly linked to the body idea for which Kant’s philosophical anthropology is the transitional moment:

“Kant’s vacillation in his basic attitude to existence corresponds to the inner conflict in his thought system. We find the strictest separation of the eternal rational substance, which he sees as the true human nature, from the sensory dimension, which he considers a subordinate, evil realm, and, contrary to this devaluation of what is natural, we get the first full view of the phenomenon of organic life as an autonomous realm between mechanistic nature and the realm of reason. . . . [T]he vacillating attitude and the inner conflicts in the system indicate that a number of shattering blows must have been struck at the old [Christian] image.”40

Á Kempis is not a peripheral figure in this genealogy; rather, he represents a “thousand-year habit of seeing” that must be “destroyed” in order for the new primal image of the (human) body or the phenomenon of life as such and its place in time and space to come to view. Instead of being a “creature of God,” a plant or animal is “a substance carrying the law of its construction within it, a substance that is not created or animated from the outside but that is itself a primary force, a substance that is not given its life from the outside but lives out of the wellsprings of its own aliveness.”

Kant’s Critique of Judgment is the closing moment of this transition to a new image of life and hence of what it means for a human being to be a living being: “Life was by then understood as a primary phenomenon in its full extent, as life of the organic individual, as life of the species, and as historical unfolding of the whole living world. . . . [T]he image of the living being as one constructed from the outside of matter and a planning power has changed into that of a substance living as a unified self-contained one out of its own inwardness.”41 Kant also plays a clear genealogical-philosophical role in Voegelin’s account: whatever insights his work may give us, his active systematization and philosophical investigations are set in a developmental and hence genealogical context.

Kant’s Notions of the Organism and Evolution

Second, in this systematization, Kant also takes part in the philosophical-scientific debate concerning the nature of an organism and a species. The end of the doctrine of divine creation brings the beginning of the concept of an organism as a “living substance with its immanent law of development.”

But an individual organism is also part of a series of organisms stretching infinitely into the past (beyond the emergence of life itself) and the future, and these immanent series are themselves related and linked to one another. Kant completes “speculation about the continuum of forms” with his “idea of the immanent evolution of the living world from the simplest forms to the most complex.”42

Again, the question of the nature of a human being emerges in a complex of images and “theories” of the living form. Kant’s distinction between “sensory nature and rational substance” in the human being is one particular construction type over against, for example, the image of an organism—including the human organism—as a unified form. The latter plays a key role in European race ideas as a way of associating cultural, intellectual, artistic, or spiritual types with genotypes and phenotypes.43

Life as Irreduceable; A New Primal Image of Man

Third, Kant stands as a philosopher of science who, in the Critique of Judgment, makes clear that the “primary phenomenon of life” is, indeed, just that, so that its three conceptual aspects—organism, species, and development or evolution—cannot explain one another.44

Finally, Kant also appears as a transition figure in the second phase of the development to a new primal image of human existence. Whereas Kant was “no longer entirely comfortable with the results of his escapist speculation on reason but could not tear himself away from the image of a soul that is perfected only in the next world,” a new image of human existence gradually emerges after him in which a daemonic figure like Goethe could come to be understood to be “the earthly and present realization of what for Kant still lay in the far-off distance as the eternal kingdom of reason at the end of the world.”45 Perfection for the individual member of an immanently rooted species becomes immanent in present space and current time, a notion that Kant could accept—if at all—only with considerable reservation.

The first three of these episodes seem far removed from political science. In several important respects they are, but body ideas and philosophical anthropology, for example, remain of politological importance. In the race books and in later episodes, Voegelin’s engagements with Kant tended to be less systematic than his analysis in “Sollen,” but several of the broad themes that we have touched on here and receive treatment in Kant’s work emerge as consistent tropes in Voegelin’s work.

Kant’s Role in Voegelin’s Developing Theory of the State

The first few encounters with Kant are still to be found in the context of Voegelin’s developing Staatslehre, where five themes cohere and predominate:

1. The nature and problems of natural science, especially in relation to human phenomena;

2. The problem of metaphysics and its contents as a legitimate field of human inquiry;

3. Philosophical anthropology as the beginning point of political inquiry (with a specific focus on human moral freedom);

4. Human “progress” in history; and

5. A theory of politics.

These five themes clearly do not denote entirely separate topical areas. Three of them are part of a problem complex for Kant, but they are not equally or similarly entangled for Voegelin.

I will briefly take them up in the order listed here. In some cases, Kant provides a new opening for philosophical inquiry. In other cases, he unwittingly obscures what had formerly been clear, or he moves in unhelpful directions. In one case, as contrasted with Voegelin’s general reception of Kant as a philosophical interlocutor, his progressivist trope serves less as the contribution of an active partner in philosophical conversation and more as an object of investigation.

Kant’s Natural Science and Political Science

The question of natural science intrudes into the problems of political science in at least two distinct ways. First, the natural sciences deliver to us the objects for rational investigation that populate the material world. Human beings are among the entities populating that world. Natural science emerges as a philosophical “question” in this context when we ask about the quality, extent, and nature of the knowledge that the methods of natural science can give us.

Here Voegelin had nothing in particular to criticize in Kant’s or even the neo-Kantians’ careful “cleansing” of the natural sciences of all methods and materials not in close conformity to the epistemological demands of the natural-scientific method and its positivist metaphysical claims.46 Human beings participate not only in the material realm that positivist natural science investigates but also in the realms of intellect and spirit inaccessible to those sciences. The positivist neo-Kantians tended to move toward a metaphysics that denied those realms any status for systematic (“scientific”) investigation, and they argued that this move was based on Kant’s work. It was a mistake, however, that Kant did not make:

“Within his system, Kant more or less applied the above-mentioned requirements [for systematic methodological purity], which neo-Kantians often simply call the Kantian ones, in his critique of the science of inorganic nature. For human life in society, however, he developed a metaphysics of reason that strongly deviates from these requirements.”47

The grounds for this deviation arise not merely out of an immediate realization—as we saw in Kant’s experience of the moral demand—that human life in society is inaccessible for essential aspects of its meaning and its structure to the methods of the natural sciences (the inaccessibility of which the neo-Kantian positivists admitted and problems concerning which they therefore discarded as “pseudo-problems”).

It also arises out of theoretical and philosophical problems that attend developments in the natural sciences themselves. Two such problems revolving around the problem of the infinite—”the dialectical conflict between the indefinite chain of empirical causality and the idea of the ‘whole of that chain and its beginning in time'” and the problem in biology of attempting to “‘explain’ the individual living organism by deriving its structure, in a indefinite regress, from preceding individuals of the same species”—were solved or “settled” in Kant’s dialectical analysis.

This settlement had its effects in the political-theoretical realm: Kant’s critique of reason regarding both problems “is limitative and has the purpose of revealing and safeguarding the ‘marrow’ of the world in the religious and moral sphere.” The subsequent result in the human sphere is a return to questions of philosophical anthropology and human historical existence in a carefully circumscribed mode.48

From Transcendent to Transcendental Metaphysics

Whether we assume the epistemological priority of the natural sciences or of questions concerning nonmaterial human phenomena, either assumption requires a metaphysical elaboration for its validation. Kant turned the question from one concerned with the transcendent to one concerned only with the transcendental. The latter reduces the metaphysical to “nothing but the inventory of all our possessions through pure reason, systematically arranged.”49 Transcendent knowledge belongs to a “hinterland,” “the regions inhabited by pre-Kantian metaphysics.”

Kant’s transcendental knowledge, on the other hand, aims not at knowledge that “wants to transcend the world, get beyond or behind it,” or at knowledge of “new objects located beyond the ‘world’… but rather at the modes of cognition with which worldly objects are grasped.”50 In this way, Kant has considerably shrunk the boundaries of metaphysical inquiry in order to preserve the integrity and validity of his philosophical enterprise.

This restriction of metaphysics, however, preserves for Kant the possibility of philosophically investigating human phenomena (freedom and morality, for example) that are inaccessible to the empirical sciences of material reality. Kant is the first in a line of philosophers, the “German idealists,” to work out a concept of metaphysics that enacts this preservation.51 Voegelin’s work required precisely this achievement.

The Letter to Hans Kelsen: The Need for Metaphysics

In a remarkably diplomatic and precisely worded 1954 letter to his erstwhile mentor, Hans Kelsen, Voegelin laid out the case for metaphysical inquiry over against the case for rejection of the same in a science of politics. His letter was in response to a missive from Professor Kelsen in which the latter had evidently expressed some “disapproval” of Voegelin’s approach to developing a political science in The New Science of Politics. Expressing “nothing other than awe and respect for [Kelsen’s] critical scientific achievements,” Voegelin contrasted the philosophical premises underlying these achievements with the premises of his own procedure.

Whereas Kelsen is a “critical neo-Kantian in [ his] theory of law” and “an agnostic in questions of metaphysics and religion,” Voegelin, while admiring the achievements of the former, does not accept the agnosticism of the latter. He rejects Kelsen’s “connection between [metaphysical] agnosticism and methodological purity,” which Kelsen argues is “intrinsic” to the scientific enterprise of the pure theory of law.

Voegelin, in other words, rejects the positivist argument that “concern with the problems of philosophical anthropology is . . . a pointless concern with unreal problems.” On the contrary, the social realm should not be strictly divided “into the spheres of normative and causal science”; a complete science of politics that is adequate to its subject matter must include “the problems of the order of the soul and the corresponding science of philosophical anthropology, which is neither a normative nor a causal science.”

This approach is, ironically enough, much more pluralist than the methodological exclusivism of Kelsen’s positivism: Voegelin could “easily recognize and accept the positive achievement of pure jurisprudence while at the same time putting a question mark against the dogmatic assertion, which [he] consider[ed] to be superfluous (because it is negative), that outside the pure theory of law there exists no legal problem which admits of scientific inquiry apart from within a causal-scientific sociology of justice.”52

The Kantian piece in this puzzle hangs on the relationship between Kant and positivism by way of a neo-Kantian critique of metaphysics. Voegelin’s 1932 article had—for him at least—put paid to the positivist assumption concerning this (negative) relationship, by showing that Kant’s epistemology, in whatever restricted form, was animated at its core by metaphysical concerns such as the human experience of freedom and moral compulsion. Whatever Voegelin thought of the adequacy or inadequacy of Kant’s formulations and explorations of those experiences, the investigations themselves put metaphysics—at first transcendental, but later, in Voegelin’s analyses of consciousness, transcendent as well—front and center as a necessary part of a complete science of politics.

Philosophical Anthropology: Kant’s Mixed Success

In “Sollen,” Voegelin had uncovered the groundwork of a philosophical “system,” the murkiness of which revealed a desire to preserve a realm of freedom required by the demands of moral reasoning, which rested on Kant’s primary experience of a binding moral injunction. Kant’s efforts “to cope with the epistemological problem raised by the new sciences of phenomena” and his efforts to understand the human being in terms of the new image of the organism merge with his conception of human beings as free and rational beings into a new philosophical anthropology.53

Kant stands near the end of the line of those “outstanding political philosophers” who could recognize the reduced, fragmentary nature of the human being left over when the natural sciences are finished with him and who were therefore “concerned with the rediscovery of man, with the arduous task of adding to his stature the elements that he has lost in the transition from the Middle Ages to the 17th century.”

These elements did not cease to exist in lived experience: they ceased only to play a role in philosophical speculation. Accordingly, “political theory must give him back his passions, his conscience, his sentiments, his relation to God, his status in history. The movement culminated, in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, in philosophical anthropology becoming the center of political thought.”54

Tracing out the primal images of human being that emerge in European race thinking was one path along which Kant’s genealogical role appeared. One could also broaden this genealogical topic to the overall destruction of the medieval cosmos through the corrosive qualities of the new natural sciences and the dissolution of the major medieval institutions, which Voegelin traced out in his (discarded) History of Political Ideas.55 Regardless of the scope of the perspective, Kant’s philosophical anthropology contained the several elements that we have already noted that gave him the “total view of human being” that Voegelin praised, even while the various elements did not all cohere into a stable whole.

Consider, for example, Voegelin’s treatment of Kant’s philosophical anthropology in another piece of the Staatslehre he was developing in the late 1920s and early ’30s, “Theory of Law.” In Kant’s theory of law, we see once again a view of the human individual in which “the metaphysical substance of human being is the finite rational person acting freely in accordance with insight into an ethical law.”

In the first instance, Kant “endeavors to determine the essence of the human being as an end in itself as a free, rational personality.” In this case, “we are in the realm of an anthropological investigation of the human being’s essential structure, which attempts to illuminate the human being’s characteristics and contrast these with the structure of such other ontic classes as the animal, plant, and inorganic.”

At the same time, Kant refers to this human essence as a “right,” which seems incoherent or even “meaningless.” Two separate issues are at work here: Kant’s philosophical anthropology and Kant’s politics, which attempt to combine and harmonize under the epistemological-metaphysical restrictions of his system the freedom and unfreedom of human beings:

“Only if a human individual is considered in regard to a possible restriction of the inherent freedom of his nature on the part of another human being can the expression of human freedom appear in the form of a demand [a “right”]. . . . It is not my freedom, which is my nature and which consequently no one can take away from me, to which I have a right, but I have a right to demand that another person refrain from interfering with it.”56

Kant constructs the (legal) dynamics of the communal interactions of these free persons in a “mathematico-physical image as the pattern necessary to sensible impressions.” As a result, his “theory of law becomes a system of equations that determines the movements of identical elements within a dynamic constellation.”

This system is based on philosophical-anthropological assumptions that Kant (as Voegelin had also uncovered in “Sollen”) does not fully articulate, and it has immediate implications for a political theory:

“This transition (to a system of equations] is made possible by ignoring the problem of human existence in its immanent-temporal and thus in its immanent-historical sphere. It can be ignored, because Kant understands the concept of essence to be identical with the content of historical reality. The essence of a human being accounts for the whole of the concrete person. The substance of a human being is a part of the universal rational substance, equal and identical to the substance of every other human being, not merely in essence, but individually. For Kant, there is no problem of a person’s singularity, of his particular irreplaceable individual essence. Humankind is a fragmentation of the pure rational substance into discrete particles of concrete, equal individuals.”57

Kant appears several more times in this mode of a constructor of the ideas of human community based on human reason whereby each human being belongs to a human community (or the “community of humanity”) “as a specimen of the rational species.”58

The specific rational content of this idea of human community also leads Kant to a speculative time construction that retains its effects in later political [imaginaries]. Kant conceives of humankind as a community of reason, the constituents of which, despite their profound flaws, are collaborating “in humankind’s great, progressive, unending work of becoming fully rational,” to a “final state of the perfect rationality of human beings.”59 We come to the problem of “progress” as a last preliminary to the problem of Kant’s political theory.

Kant’s Dilemma

The Enlightenment doctrine of infinite immanent progress toward the perfecting in reason of the human race is well known. Equally well known is Kant’s conflicted evaluation of this doctrine. His attitude was “determined, on the one hand, by his conviction of the shortcomings of human existence and, on the other, already colored by a sense of the meaningfulness of existence.”60 Human progress toward immanent perfection had the following problematic: “Where will this continual progress of science lead us? What is the benefit to us men here and now from the fact that in the future others will live in a more perfect realm of ratio? Our life will be unaffected by that [final end].”

Voegelin’s solution to Kant’s dilemma composed a core aspect of his own philosophical work: this last meaninglessness, which aroused Kant’s sense of “alienation,” can be resolved only by openness to transcendence in the sense of life’s opening toward meaning. It does not lie in the world.61 The development of a primal image of life in which “the living being as one constructed from the outside out of matter and a planning power had changed into that of a substance living as a unified and self-contained one out of its own inwardness” made such an openness to transcendence more difficult. And such openness finally came to a close with Kant’s concept of the organism. 62

For Kant, however, reason was the defining quality of human beings. Since the capacity for reason admits of many individual shortcomings, it is only in its manifestations in the human species that one may hope for long-term progress toward its perfection or completion. As Kant wrote: “But no matter how puzzling this may be, it will appear as necessary as it is puzzling if we simply assume that one animal species was intended to have reason, and that, as a class of rational beings who are mortal as individuals but immortal as a species, it was still meant to develop its capacities completely.”63

Voegelin was inclined at times to consider Kant’s treatment of this problem an Enlightenment “apocalyptic of history.”64 It seems to me, though, that however much or little Kant contributes to this apocalyptic spirit, the impulse that engenders it is the same impulse that Voegelin noted in “Sollen,” namely, a recognition of moral imperatives that require a realm of moral freedom. Thus Kant wrote:

“If he lives among others of his own species, man is an animal who needs a master. For he certainly abuses his freedom in relation to others of his own kind. And even although, as a rational creature, he desires a law to impose limits on the freedom of all, he is still misled by his self-seeking animal inclinations into exempting himself from the law where he can. He thus requires a master to break his self-will and force him to obey a universally valid will under which everyone can be free. But where will he find such a master? Nowhere else but in the human species.”65

Voegelin recognizes that in Kant’s philosophical anthropology, which understood the human unitary form as composed of organism (animal) and reason (exclusively and specifically human), he insisted on balancing–however precariously–the idea of progress with “belief in the true fulfillment of the meaning of life in the beyond.”66 Contrary to one pole of Kant’s thinking, Voegelin would conclude that “history has no knowable meaning (eidos or essence),” and that “there remains a core of the unknowable in the nature of man.” Accordingly, “the relation between personal fulfillment and the partnership in the fulfillment of mankind is a mystery.”

Much Sobriety and Too Little Political Substance

At the other pole of Kant’s thinking, “the Kantian question” concerning “what interest a generation of man at any given time could have in the progress of mankind toward a cosmopolitan realm of reason,” is a “sober question” in the context of and in contrast to the “progressivist intoxication of the eighteenth century.”67 Kant’s sobriety did not keep him from falling especially short in questions of political substance. This was apparent in his careful delineation of the characteristics of the phenomenon of life under the new immanentist primal vision and the phenomenon of finite human, rational (infinite) life under that same primal way of seeing,68

Kant found himself in a vicious circle. He remained skeptical of a political solution in which–under the new primal way of seeing–a great individual could bring moral order, let alone moral perfection, to a society, because “for him practical humanity was nothing more than the existence of man under the moral law out of pure reason, and the problematic of the infinity of the rational substance was precisely the basis for the circle. For Kant, finite reason was by nature corrupt and could never be the source of a pure, meaningful fulfillment of earthly existence.”69 We observe the dictates of his epistemology similarly imposing formal patterns of machinelike interfacing on his image of the law and legal interaction.70

Voegelin ultimately “escaped” from Kant’s apparent dilemma when he came fully to realize that Kant’s conception of the human being as a “subject of cognition” in these various systematizations was–perhaps–sufficient in the realm of a specific range of empirical data, but not in the realm of an exploration of “the concrete consciousness of a concrete human being when confronted with certain ‘subjective’ deformations.”71 Rather, “An analysis of consciousness . . . has no instrument other than the concrete consciousness of the analyst.” The conclusion that follows is at its root severely anti-Kantian:

“The quality of this instrument, then, and consequently the quality of the results, will depend on what I have called the horizon of consciousness; and the quality of the horizon will depend on the analysts’ willingness to reach out into all the dimensions of reality in which his conscious existence is an event; it will depend on his desire to know. A consciousness of this kind is not an a priori structure, nor does it just happen, nor is its horizon a given.”

“It rather is a ceaseless action of expanding, ordering, articulating, and correcting itself; it is an event in the reality of which it partakes. It is a permanent effort at responsive openness to the appeal of reality, at bewaring of premature satisfaction, and above all at avoiding the self-destructive fantasy of believing the reality of which it is part to be an object external to itself that can be mastered by bringing it into the form of a system. What I had discovered was consciousness in the concrete, in the personal, social, and historical existence of man, as the specifically human mode of participation in reality.”72

In light of this conclusion, to review further details of Kant’s philosophical-anthropological constructions as Voegelin finds them and compares them with those of other philosophers would derail us here, since Voegelin’s sole intent was, indeed, to bring (back) to light the philosophical problem of linking body to mind to spirit in some kind of theoretical construction that remains faithful to the basic human experiences of being a whole made up of connected parts.73 Kant, like Aristotle, provides a construction that “[presents] the autonomy of the parts [it] unifies,” and in which one part claims superiority over all the others. These construction types may be contrasted with the Cartesian, the late romantic, and the “intellectual unity” constructions.

Voegelin’s evaluation of Kant’s construction in the context of the race books and even the emerging Staatslehre ended with the observation that Kant’s and Aristotle’s constructions “have no epistemological value,” serving “merely to illustrate the problems resulting from the fundamental experiences: the philosopher is forced (1) to reinterpret the contrasting components of experience as functions of the human totality, and (2) to posit a relationship between functions strictly and inherently separated from each other.”74

Kant’s Theory of Politics: The Constitutional Escape

The several problematic elements of Kant’s systematization in metaphysics and philosophical anthropology, which we may summarize from the preceding discussion, coalesce in his theory of politics. They include his impoverished view of the sociological aspects of human existence, his excision of all “heteronymous” content in human moral judgments from philosophical consideration, the parallel problem of his legal formalism, and his essentialism with respect to the role of reason and freedom in human individual, species, and historical existence.

Kant’s emphasis on freedom as the morally and rationally necessary quality of human beings was, he knew, not adequate: we are, after all, embodied beings, participating in a physical realm of necessity as well as the metaphysical realm of freedom. This anthropological datum produced a practical puzzle for Kant. These two realms are somehow linked, and we experience such a link in the practice of politics. If the “master to break [the] self-will [of human beings] and force [them] to obey a universally valid will under which everyone can be free” could be found “nowhere else but in the human species,” the implication was a political solution:

“But this master will also be an animal who needs a master. Thus while man may try as he will, it is hard to see how he can obtain for public justice a supreme authority which would itself be just, whether he seeks this authority in a single person or in a group of many persons selected for this purpose. For each one of them will always misuse his freedom if he does not have anyone above him to apply force to him as the laws should require it. Yet the highest authority has to be just in itself and yet also a man. This is therefore the most difficult of all tasks, and a perfect solution is impossible. Nothing straight can be constructed from such crooked wood as that which man is made of.”75

Kant’s way out of the circle was constitutionalism. Within a formal legal structure that vested authority among officeholders, established constraints on the exercise of power, institutionalized procedures for ensuring the accountability of officeholders and officials, and legally guaranteed the rights of citizens,76 the “crooked wood” of which humanity is made could be shaped into a community of cooperation and, it would seem, of infinite progress toward rational perfection. There is, however, a severe tension in this schema.

Kant, along with others who shared his primal view of humankind, “saw the idea of man in his reason and formed the idea of community of a humanity to which each man belongs as a specimen of the rational species.” For Kant, this idea of humankind eliminates from consideration problems of political culture, political sociology, or any other empirical considerations of human rootedness in particular space and time. Thus, “the species-wide animality specific to human beings appears as the general human connection between the mind and the sensory nature in which the mind must live its life.”

For Kant, “from this follows the idea of the humanity in a community in which non-sensory mind articulates itself in animal-sensory variety.” It is possible under such a construction to develop an “idea of community in which all people, as belonging to the same species and therefore incurring a shared fate, are faced with the same ethical community obligation of overcoming animality and purifying the mind.”77 Kant’s abstractions, however, and his “idea of man in his reason” tend to eliminate pragmatic particulars along this line. As with other constitutional schemas, Kant’s constitutionalism ignores questions of political education, political leadership, or the building of political or social consensus around pragmatic or moral problems.78

Overcoming the “Crooked Wood” of Humanity

Kant overcomes the “crooked wood” of human (animal) nature by regarding humanity above the individual as a species whose core attribute is reason. At any particular point in time, moreover, “nature only requires of us that we should approximate to this idea” of human perfectibility.79 Thus, “We see a human in society, but in the society of all of humanity as a species. Bearing within himself a noumenal core, he is at the same time a sensory being. His sensory element, however, adheres to him as something external, insubstantial, contemptible, and worthless, and if he seeks perfection, he should let his actions be guided by reason alone.”

“Reason alone” means that the moral individual should pay no attention to the consequences in “the sensory world” of his rationally determined moral actions, nor should such actions be influenced by pleasure, pity, friendship, or love.80 These belong to the realm of nature, “inhabited by phenomena or appearances, related to man through knowledge, and characterized by the principle of necessity.” If we consider for even a moment the role such motivations play in classical conceptions of personal or political ethics, we see how severely abstracting this Kantian injunction is. Sociologically, too, the individual “must not accept the norms of his class [aristocrat, bourgeois, or peasant] as the motive of his actions.” Rather, the individual must pay attention to a morality that resides in a realm that is “inhabited by noumena or the intelligible, general grounds of appearances, related to man through action, and characterized by the principle of freedom.”81

The kind of constitutionalism that Kant espouses depersonalizes politics by emphasizing “correct method,” which overall leads to “leveling tendencies” in the political life of the constitutional polity; many of us who inhabit such a regime might consider the specific, “personalized” features of its political life to be beneficial, not drawbacks. This depersonalization by means of a leveling method excludes “the art of politics.” Perhaps because of the flawed beings (“crooked wood”) that inhabit that polity, however, “the theory that emerges is not so much one that eliminates politics but trivializes it,” as was noted by Sheldon Wolin.82

Voegelin noted the tension between the “doctrine of misery of the cultural condition” of the individual human being and the doctrine of the ultimate historical perfection of the human species in moral reason creates a “disjunction between the perfection of the person and the perfection of the species that Kant never succeeded in constructively resolving.”83 This disjunction also explains Kant’s peculiar affirmation of tyrannical rule while holding to the doctrine of historical perfection and to a doctrine of natural law in which the natural law describes for us our moral duties and our freedom (“rights”) under a law of reason. In its actual application to the world of empirical politics, the doctrine of perfection is a “possible nature whose moral dimension has been attached to it for heuristic use.”84

It is, in other words, a teleological principle under which our moral determinations are regulated, but not necessarily a practical political principle for any given moment of political decision. After all, Kant appends to this historical hope a conservative doctrine of political obedience,85 and he adds to that doctrine a further contradiction: the historical “improvement” of humankind comes about through the exercise of self-interest, whether it be the exercise of counterbalancing self-interest in the constitutional polity (the famous “nation of devils” being the most extreme case of this principle)86 or the self-interest of the enlightened despot, whose policies for economic growth in fact encourage the rational development of the population.87

That which Kant condemns in his moral philosophy, namely, that “interest” (or any other “heteronymous” principle) could be a source or criterion of moral goodness, moves to the center of his political philosophy, where it serves the teleological ends of nature in historical development toward immanent human perfection.88 This meager, somewhat self-contradictory political theory will be familiar to most readers, because they likely live in a regime constructed, to some degree, on its premises.

Voegelin and Kant: A Limiting Dependency?

We have thus far taken Voegelin, as it were, at his word. Kant’s efforts to retrieve a view of humankind from the emaciations of sixteenth- and seventeenth-century developments in the natural sciences provided Voegelin with several entry-points into a recovery of a political science based on a philosophical anthropology that was credible from the perspective of natural science yet not exclusively based in that mode of knowing. Voegelin deployed those Kantian efforts as they afforded him congenial doorways into important questions, and critically rejected them if they led to culs-de-sac. There is yet another sort of “influence” in the work of a thinker, however, that deserves further consideration.

John Ranieri has persuasively argued that, in at least one important respect, Voegelin lays a Kantian track into the very core of his own philosophical enterprise. Following the lines of a Platonic-Augustinian dualism in epistemology and ontology that seems all too consistent with Kant’s dualistic epistemological division between the realm of reason-freedom and the realm of necessity, Voegelin divides the realm of the consciousness of the individual human being from the mundane world of everyday existence.

This division has frequently frustrated Voegelin’s readers, because it seems to some of them that, for Voegelin, “events such as the leaps in being occur primarily in the consciousness of their recipients, leaving largely unaffected the ‘external’ phenomenal world governed by the laws of mundane existence.”89 This dualism is sharply and deeply indicated in a passage concerning the “double constitution of history,” in which Voegelin brings Kant’s language directly to hand.

“History,” argues Voegelin, “has a phenomenal surface that can be explored by an objectifying science, but the enterprise of science makes sense only as long as the facts ascertained can be related to the noumenal depth of the encounter.” Unlike in physics, where the precise ontological relationship between noumenon and phenomenon remains unknown, “the noumenal depth of the encounter” in history “involves man in the constitution of being; and the process leading from the encounter, through the experiences, to their expression, again involves man in its constitution at every step.” The noumenal and phenomenal aspects of historical events are therefore related in the act of recounting them and thereby “making” history: “The surface of the process does not have pre-given definiteness of constitution; it is not given at all but constitutes itself in the acts of symbolic expression.”90

Ranieri’s broadly elaborated concern is essentially this: Voegelin’s extensive efforts to show that human history is constituted in good part “through human acts of meaning” were undertaken with an insufficient departure from “the positivist views he wished to oppose.” These views rested on a neo-Kantian epistemology that was reinserted into Voegelin’s analysis in this instance by his recurrence to Kant’s dualistic-idealistic epistemology in the realm of physics as a partial analogy to historiography and historicization. “The idea that history has a double constitution,” Ranieri cautions, “can lead to a situation in which history is understood as being divided into two realms whose relationship to one another is not altogether clear.”91

As Ranieri unfolds it in his examination, Voegelin’s approach—influenced as it is by Kant’s dualistic epistemology—seems to smuggle into the analysis of political acts and historical events a latent conservatism, bordering at times on either quietism or a “realist” conformism, that is warranted neither by the dualism itself nor necessarily by pragmatic evaluations of the specific circumstances. What, for example, of political reform, of better or worse policy toward intractable yet perhaps ameliorable problems of the commons? Was Isaiah’s advice to King Ahaz truly insane? Is the pragmatic world of necessities completely unchangeable, or is some political improvement from time to time and however transitory possible?

Voegelin’s division of the realm of spirit and the realm of the mundane tends toward this dualism, Ranieri asserts, because he insufficiently clarifies the relationship between these two as indicated in the questions of pragmatic politics that I have listed and that could be multiplied. Voegelin’s treatment of Israel’s intramundane history in comparison to its spiritual history certainly reflects this division,92 and Voegelin consequently says perhaps too little about pragmatic yet ameliorative political activity.93 It remains to consider, however, whether Kant or Plato is the more central figure to this understanding of politics.94

In the Grand Scheme: Kant as Voegelin’s “Star Friend”

Having recovered–in Voegelin’s careful estimation–an eye for the essentials, Kant was unable to develop that recovery beyond the strictures of the formal philosophical framework within which it had taken place. Had the present essay been written in the natural scientific mode, it might have begun with a hypothesis: a reader would find significant influences of Kant in Voegelin’s work, and Kant would play a major role in Voegelin’s early material. That hypothesis would have been disconfirmed.

Indeed, given the paucity of references to Kant in the now published papers surrounding Voegelin’s Herrschaftslehre, especially in view of his frequent mention of other philosophers,95 we might be forgiven for wondering if Kant served as anything more than a foil for initiating a subterranean critique of positivist political theory. Certainly, he does not serve up for Voegelin the kinds of substantive, positive beginning points and contents to be found in the works of Othmar Spann, Georg Simmel, Henri Bergson, Edmund Husserl, or others.

Nevertheless, imputing nothing more than the role of a foil would be going too far; at the least, it would obscure the ways in which Kant’s philosophy was, in fact, an element—offering not merely an occasion for disposal—of the wide-spanning philosophical conversation in which Voegelin was taking part. More important, such a conclusion would hide completely at least one important way in which Kant’s “influence” on Voegelin’s thought may have had a less than salutary effect. It would also miss the nontrivial ways in which Voegelin shows us how to engage as a partner in discussion a thinker who may, in Nietzsche’s apt term, be a “star-friend”: a thinker in opposition as an “earth enemy,” yet reaching, perhaps, for recognizably similar ultimate goals.96

Notes

1. Eric Voegelin, The Collected Works of Eric Voegelin (hereafter CW), 34 Vols. (Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 1990-2009), Vol 25, History of Political Ideas, Volume VII: The New Order and Last Orientation, ed. Jürgen Gebhardt and Thomas A. Hollweck (1999), 23.

2. Voegelin, CW Vol 18, Order and History, Volume 5: In Search of Order, ed. Ellis Sandoz (2000), 127-28; Voegelin, CW, Vol 7, Published Essays, 1922-1928, ed. Thomas Heilke and John von Heyking (2003), 336; Voegelin, CW 25:23.

2A. Voegelin, CW Vol 12, Published Essays, 1965-1985, ed. Ellis Sandoz (1990),304-14.

3. Voegelin, CW 7:336; Voegelin, CW, Vol 12, 304-5.

4. Barry Cooper and Jodi Bruhn, eds., Voegelin Recollected: (Conversations on a Life (Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 2008), 266. It is perhaps worth noting that this is the only mention of Kant in 278 pages of recollections from friends, associates, students, and relatives of Voegelin.

5. Voegelin, CW Vol 5, Modernity without Restraint: The Political Religions; The New Science of Politics; and Science, Politics, and Gnosticism, ed. Manfred Henningsen (2000), 261-65, 268-70; Voegelin, CW Vol 18:65-67.

6. Voegelin, CW Vol 18:13-14, 63-64. The details of this initiation are not of immediate concern here: Voegelin’s analysis is sufficiently compact that the reader should refer to the text itself. [The text, at p 63, uses the phrase “layers of proportional incrustations” but it seems “layers of propositional incrustations” is clearly meant, with “propositional” also being used in the following sentence, and so it is printed here. VoegelinView Editor.]

7. Ibid., 63-64.

8. For a discussion of some of the problems involved, see Thomas Heilke, “Anamnetic Tales: The Place of Narrative in Voegelin’s Account of Consciousness,” Review of Politics 58 (Fall 1996): 761-92.

9. Voegelin, CW Vol 18:63-64.

10. For what is arguably the most formidable critique of this account of knowing, mostly overlooked by Voegelin scholars, see Michael Polanyi, Personal Knowledge: Towards a Post-Critical Philosophy (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1974).

11. Voegelin, CW Vol 5:98-105.

12. Voegelin, CW Vol 12:305.

13. Voegelin, CW Vol 6, Anamnesis: On the Theory of History and Politics, ed. David Walsh (2002), 33.

14. Voegelin, CW Vol 8, Published Essays, 1929-1933, ed. Thomas W. Heilke and John von Heyking (2003), 180-227. The original is “Das Sollen im System Kants,” in Gesellschaft, Staat, und Recht: Untersuchungen zur Reinen Rechtslehre: Festschrift für Hans Kelsen zum 50. Geburtstag, ed. Alfred Verdross (Vienna: Julius Springer Verlag, 1931), 136-73.

15. Voegelin, CW Vol 4, The Authoritarian State: An Essay on the Problem of the Austrian State, ed. Gilbert Weiss (1999), 16-18.

16. Voegelin, CW Vol 8:180. For further details of this endeavor, see the editors’ introduction in ibid., 1-24.

17. Ibid., 181, 222.

18. Immanuel Kant, Prolegomena to Any Future Metaphysics, ed. and trans. Lewis White Beck (Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill, 1950), 8.

19. Leslie Newbigin, The Gospel in a Pluralist Society (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1989), 18.

20. Voegelin, CW Vol 8:204, 210, 212.

21. Ibid., 17. For an examination of Voegelin’s critique of Kelsen that emphasizes the neo-Kantian character of Kelsen’s work, see the essay by Arpad Szakolczai included in this volume.

22. Ibid., 215.

23. Ibid., 216. Again, this aim would not be apparent from Kant’s own synopsis of a work that he describes as “dry, obscure, opposed to all ordinary notions, and moreover long-winded” (Prolegomena, 9).

24. Voegelin, CW Vol 8:217.

25. Ibid., 218, 220.

26. Ibid., 221. Voegelin’s run-on sentence in this context strikes me as a “poetic” way of displaying that which he wants to critique. Cf. pp. 206-9 for a second critique of Kant’s “intentional vagueness” as an essential aspect of his philosophical project.

27. Ibid., 223-25.

28. Voegelin, CW Vol 5:105-7. Again, Voegelin’s critique of Weber in The New Science of Politics (ibid., 105-8) is instructive. Kant receives not a single mention in this work, though he does reappear in later analyses as a significant figure.