Introduction the Subfields of Political Science: Canadian Politics

After considering the “big picture” questions about politics, my first-year students turn to the study of Canadian politics (in the U. S., this subfield would get covered by an Introduction to U. S. Government and Politics, though, for reasons I’ve discussed previously, American university students frequently receive Introduction to U. S. Government and Politics as their formal introduction to the overall discipline of Political Science).

After hearing about the tension between politics (treated generically, in the form of the laws of Athens) and philosophy – both as reflecting distinct ways of life – we lower our gaze to within the political horizon to consider the nature of the regime in which my students live. This lowering of our gaze comes as a bit of relief for many of my students, who can now get a chance to study politics in a form with which they are more familiar. It also comes as a bit of a disappointment for those who may have caught the Socratic bug. But teaching is not a risk-free enterprise, so we must carry on.

One of disadvantages of considering the Socratic dialogues at the outset of the semester is that it tends to obscure the differences among political regimes. From the Socratic perspective, Athenian democracy looks a lot like any other political regime – including tyranny – because the difference among political regimes is smaller than that between the way of life of politics and the way of life of philosophy.

Still, there is a difference between Athenian democracy and tyranny or oligarchy. And there is a difference between both of those and modern liberal democracy, as presented in the form of the idea of responsible government in Canada.

The best introduction to Canadian politics I can think of is the ratification debates that took place after the constitutional document had been drafted. These debates are abridged in a wonderful volume, Canada’s Founding Debates, edited by Janet Ajzenstat, Ian Gentles, Paul Romney, and William Gairdner. Here we read why Canada’s Founders chose the form of responsible government they did, over and against alternatives. Canadians, who have inherited this system, are oblivious to its foundations, and the reasons for those foundations. This ignorance is not restricted to Canadians; it is the general condition of citizens everywhere who are accustomed to the benefits of their regime without being fully aware of why they are benefits.

Even so, one of the reasons they published this volume is the utter, and appalling, ignorance about the Founding among not just the Canadian public, but Canadian political scientists. Unlike the United States, where the Founding debates are easy to obtain, and where studies of the Founding are an academic industry, the Canadian debates, before Ajzenstat and her colleagues published them in abridged form, were rarely published and rarely examined by scholars.

The ignorance of Canadians is not simply a matter of the limited horizon of the citizen, but part of it is willful and imposed because Canadian political scientists and historians determined, without bothering to study the sources, that Canada’s history is progressive; what’s important is to come, and not what has occurred. It’s as if to confirm Aldous Huxley’s warning that modern tyranny requires ignorance of history. With Huxley’s Brave New World still in their memories, the students feel cheated at having their history taken away from them. I am not above turning the resentment undergraduates have against their rulers and elders into a healthy skepticism toward the ideology of progressivism that reigns strongly in Canada, perhaps even more strongly than in the United States. There is something satisfying with turning youthful attitudes against the unseemly youthful attitudes of the old.

Like the subjects of Brave New World who think their history begins in the 1 A.F. (“After Ford”), the youth of Canada tend to regard 1982, the year the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms was introduced, as their Year 1 in the era of freedom. Before 1982, Canadians lacked liberty. This, of course, is nonsense, and reading the Founders enables them to see the genuine origins of their regime.

The ignorance of Canadians for the ideas and beliefs of the Founders, as well as the character of the founding act, has bred a lot of confusion. Canadians have been taught that their Founding was simply a pragmatic act by pork-barrel politicians who, if they could barely arise to articulating principles, certainly could not implant principles into their constitution. They were too partisan. They were elitist if not aristocratic. Americans are familiar with these forms of accusations against their own Founding. But at least there are enough American scholars who know something about James Madison and other Founders to counteract those accusations.

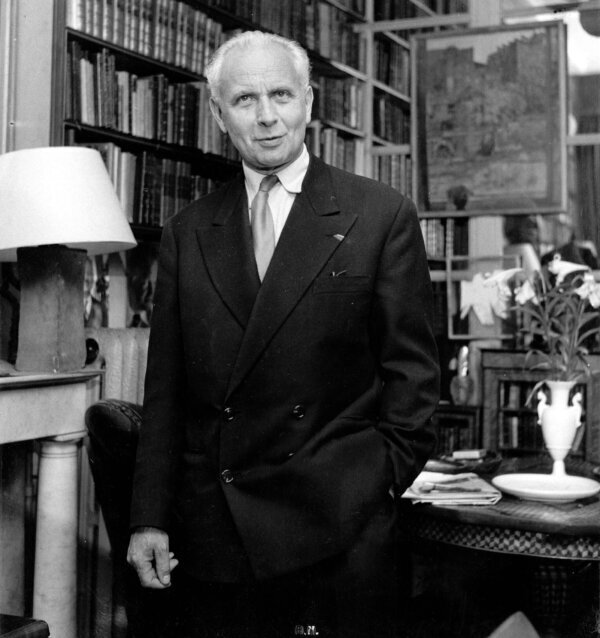

The main source of confusion for these accusations is the belief that the Founders were Tory conservatives who wished to apply British aristocratic constitutional forms to Canada. Thus, it is said that the Canadian Founders were Burkean conservatives while the American Founders were Lockean liberals. One of Canada’s most notable philosophers, George Grant, wrote a book, Lament for a Nation, predicated on this mistake.

However, in reading the debates, one finds they passionately defended key Lockean principles including liberty of the individual, consent of the governed, equality, responsible government, separation of powers (in the forms of responsible government). They also defended some American principles including federalism. On the whole, though, they tended to think the U.S. had gotten too plebiscitary which had led to its Civil War (the debates occurred during the Civil War, which tended to illuminate the weaknesses of the U.S. regime to them).

If the Founders look conservative or Burkean, it is in their desire to restrict the franchise to property owners as a way of promoting responsibility among voters. I explain to my students that home owners tend to care for their property better than renters, a point they immediately understand from their own experience as renters who remember the cleanliness of the family home they have since departed.

The “Tory” appearance of the Founders is also seen in the tendency among some of them, most notably John A. MacDonald, Canada’s first Prime Minister, to look to the state to solve national problems. However, one looks in vain to see distrust in the market. If anything, the Founders defend free markets, not only on its own terms, but as a precondition for responsible government. They view the Founding as a way of increasing export markets for the different provinces, and also because responsible government depends on a society with diverse interests that a large economy produces (the Federalist makes the same argument concerning the extended republic).

A better way to view MacDonald’s desire to use the state to solve national problems is the fact that he saw the state fit to build a nation that had just come into being. Building a national railroad, a key part of his nation-building exercise (and one disdained by many people in what would become western Canada), is an action perfectly in accord with many free-market principles. It is an example of infrastructure, which the market may not be able to build. It is no surprise, then, that, in MacDonald’s copy of the Federalist that is housed in the National Library in Ottawa, it is the papers by Alexander Hamilton that are the most marked up.

In reading the Canadian Founders, my first year students have a case study in the basic meaning and functioning of liberal democracy. They consider the meaning of liberty (is an end in itself or does it serve a further goal, such as human happiness?), equality (of opportunity or result?), economic opportunity, ambition (many Founders thought Confederation would expand the sphere for talented ambitions), representative government versus direct democracy (they debated whether the Constitution ought to be ratified by legislatures or in referenda in the provinces), and responsible government.

In each iteration of the class, I have time to focus only on a few of these themes. In the most recent iteration, I focused on the meaning of responsible government, with an eye on the difference between it and how the Founders viewed the U. S. constitution.

Contrary to the popular image of the Founders as dedicated to statism, they thought their system of responsible government offered greater individual liberty than the U. S. system. The Canadian Founders agree with their American counterparts with the end of politics, but they thought their system of responsible government offered a more effective means of obtaining it. The idea of responsible government is that government (the Prime Minister and his Cabinet) are sitting members of the House of Commons, and government needs constantly to secure and maintain the support of the House. If working properly, members of government should be in constant fear of getting the “heave” because nary a day goes by when the House could withdraw its support. Parliament in Canada doesn’t quite work this way (though Australia, New Zealand, and Great Britain seem to have retained this practice better) because, many argue, power has been centralized in the office of the Prime Minister (though this argument has its detractors). Whereas the U. S. President faces the electorate every four years, and Members of Congress frequently face the possibility of having their bills vetoed, government in responsible government perpetually seeks support from its peers on a daily basis.

Perhaps the Founders’ belief in responsible government, and its superiority over the U. S. system of separation of powers, is due to an insight Machiavelli makes in Chapters 9 & 18 of The Prince. There he states the prince should base his rule on the many instead of the great because the former are easy to manipulate. The many only have a passing and distant interest in the affairs of state, while ambition makes the great take continuous and close interest in those affairs (at the prince’s expense). When Canadian political parties decided to choose their leaders by its membership instead of by caucus, they seemed to have inadvertently followed Machiavelli’s advice for princes. In their desire to democratize responsible government, later reformers forgot something essential about responsible government.

In learning about responsible government, students also learn that it differs from democracy. Further, they learn the wisdom of having institutional restraints – or what Tocqueville describes as forms – on democracy. They learn that not all problems democracies face can be solved by creating even more democracy. They learn the age-old wisdom that a mixed form of government, guided by a statesman’s practical wisdom, may be the best practical solution to political problems.

Also see “Ditching the Textbook,” “What is Politics?” “Political Philosophy,” “International Politics,” “Comparative Politics,” and “Big Questions for Contemporary Politics.”