Leadership and Machiavelli

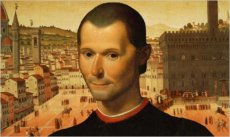

Scholars, practitioners, and more casual observers of leadership often talk about Niccolo Machiavelli in the context of leadership practices. Substantially fewer seem to be well read on the (in)famous Florentine. It is possible to consider Machiavelli, his writings, and ideas reputed to him, in a better, more informed, less condemnatory and more positive light. This essay will try to show how and why Machiavelli has been substantially misunderstood and misrepresented in modern discussions of leadership and how a different understanding of his frame of thought can inform our thinking about leadership.

Machiavelli is of such historical standing that he ranks among those for whom no given name is needed. He stands virtually alone as a thinker and writer understood to convey a “realistic” approach to politics and leadership which requires a ruthless, self-interested, and amoral or, to many people, immoral practice. This perception results from a tendency to read (or read about) only his most widely known s work, The Prince, and not to put it into context by reading the rest of his works, especially The Discourses (more properly known as Discourses on Titus Livy). The conclusion often drawn from this short-changing of Machiavelli is that the model of leadership practice developed in The Prince is advice on how to be a leader in the real world. But, closer reading suggests that Machiavelli did not hold so simple a view.

The following exposition on Machiavelli is not meant to be comprehensive, but to challenge. It rests on the observation that Machiavelli imagines leadership arising out of a more complex set of causes and having necessary affects that are not encompassed by reading The Prince, alone. His ideas have more to do with the potential success of the human community than with the achievement of particular leaders.

Central to these ideas is the contrast between the two books on the way societies should be and the way they, in fact, most often are. It is this dichotomy that reveals Machiavelli’s concern with understanding why and how societies succeed or fail. In his two models, the primary burden of responsibility falls on citizens in one case and a ruthless leader (the Prince) in the other. In a republic, leaders are balanced and checked by a virtuous citizenry who care for the community at least as much as they care for themselves. (Perhaps because they care for themselves in a way that is inseparable from the community.) In a sense, Machiavelli’s republic is the ‘good’ society whereas the principality is the less “evil” choice between order and disorder that must be made when the republic fails.

It is important to recall that the Prince rises to re-establish order in a society that has descended into disorder following the citizenry’s loss of virtu’ – the capacity to rule themselves in the interest of all. Of particular interest is the idea that a principal reason for this loss of capacity and commitment is the rise to dominance of particular or narrow self-interest divorced from the well being of the community and to the exclusion of commitment to the welfare of others. (It may be useful to recall that Machiavelli predates modern liberalism and its somewhat odd notion that narrow self-interests can interact, especially in the marketplace, to produce the common good. (See the treatment by Stephen Holmes) Indeed, Machiavelli understands that a successful and virtuous society must be composed of citizens who link their own interest to the community, even at the cost of their own narrow self-interest. It can be argued that his concept of the virtuous citizen/leader requires, at its best, a unification of self-interest and community interest to such a degree that the pursuit of narrow self-interest is, in fact, the negation of virtu’ and, thus, the prime cause of the failure of the community.

Machiavelli fails directly to address the question of virtuous leadership in a republic, even thought the inferences that may be drawn are clear enough. It is not reasonable to conclude that Machiavelli’s republic is composed only of virtuous citizens who need no leaders of their own. Rather, we may suggest that he intends the official and/or informal leadership of the community to share a common virtu’ with all citizens. It is this high standard that is likely to erode as individual citizens and leaders begin to serve lesser, more self-centered ends.

In the end, Machiavelli’s common denominator for leadership is a capacity to commit to purpose. When the citizens of the virtuous republic lose their commitment to the commonweal the community can be maintained in much less perfect form only by the strength of a prince. The differences between the types have to do with the ruthlessness required of a leader in trying to restore and maintain order when citizenship fails; citizenship being the capacity of each person in a society to commit to a common purpose in the sustenance and preservation of the community. Absent that commitment to a common purpose, the prince must impose order by whatever means necessary.

Clearly, commitment to purpose begs a question as to the virtue of the purpose itself; to this Machiavelli speaks only obliquely. The most just state of social existence for him, it seems, would be one in which all people are consciously governed in their own actions by a sense of obligation to each other. That he may have doubted the possibility of this in the real world does not detract from its value as an ultimate standard. Indeed, the Machiavellian perspective, read as suggested here, invites us to revisit the classical perspective in which the just society is not merely the optimally productive in material goods.

Consider, for example, the difficulties attendant on the clash between the idea of universal human rights and the idea of national sovereignty wherein each nation’s right to separately and differently define virtue is treated as the supreme right and necessity of existence. Similarly, consider the western notion of “individualism” which tends to eschew both the individuals responsibility for the community and the communities responsibility for the individual -this despite the contradictory impulse evident among many to hold the individual responsible for his/her own acts according to assumed pre-established community standards! These suggest simply an elaborated version of Machiavelli’s decayed republic in which the common interest is sacrificed to selfish, individual interest and the community interest becomes merely a corrupted extension of the dominant combination of narrow selfish interests. In essence, it is possible to suggest, Machiavelli’s approach can take us to the realization that leadership and power are distributed among citizens in the virtuous republic whereas in its fallen state they are concentrated in the hands of a prince! Indeed, more modern but still “classic” works supporting the modern state such as the Federalist Papers suggest an overriding concern with creating a workable republic based on both restraining the prince and containing the people! But, many contemporary students of leadership and organization point to a need for greater cooperation and more widely distributed leadership.

This reading of Machiavelli suggests that some significant paradoxes exist with which we must continue to struggle. First among these is the implication that the virtue of leaders in the “good republic” is proven by their success in rendering themselves superfluous or temporary. Sydney Verba observed this as a major characteristic of successful “democratic leaders” in his Small Groups and Political Behavior: A Study of Leadership (1961). He also noted that such “democratic leadership” became much less likely as the group size increased beyond 20 and, in fact, was only significantly possible in groups of seven or less. Indeed, many studies of small group behavior supported the observation that “as the size of the group increases, there is a tendency toward less free participation on the part of group members and toward the concentration of group activities in the hands of a single leader.” (p. 36) [Reminiscent of Robert Michels, Political Parties]

The second paradox follows from the implications of the first: leaders tend to emerge in larger groups who come to resemble Machiavelli’s Prince more than his virtuous republican citizen/leader. Is this because order becomes an increasingly significant second-order value (necessary for the realization of all other values) as the size and complexity of the group increases? That is, as the dominance of a single leader increases as the size of the group increases does the desire for order tend to suppress the emergence of leaders from the smaller sub-groups, both formal and informal, within the larger group – at least partly in the name of keeping order? It seems that democratic groups and organizations will begin to lose their “virtu’” as they suppress the free, participatory, smaller groups (3-7) and the leaders they spawn; leaders who can not only provide a reservoir of successors for the group or organization but a set of communication nodes capable of carrying a common message and defining a common mission. Significantly, much of a Prince’s power will be provided by the passive acquiescence of the members of the group who come to willingly distance themselves from the greater responsibilities of citizenship. The most insidious element of this process is that in which the citizen, already corrupted by narrow material self-interest, is persuaded to accept more material gratification as a substitute for both personal and social virtue. Thus, all meaningful hope of adherence to a universal standard of right seems doomed.

This dark picture is not unrelieved, however, since it remains possible that leadership can emerge which produces, or arises from, a universe of leaders cooperating in the creation of the human community. The world may not be saved by a single leader but by many leaders who seek a common message and mission. It is probably true that such an ideal significantly overreaches real possibilities, and certainly begs the question of conflict between substantive and procedural values, but is not the vision of (and hope for!) leadership that speaks for all humanity the ultimate cause of our fascination with the subject? Do not most modern organizations seek ways to release the creativity of their members? Calls for participative management and relationship-centered leadership reflect at least some realization that a culture based on individualism, competitiveness, and hierarchy has its limits and flaws. The Machiavellian imagination suggests that a return to the virtue of many leaders is what should call to us, not the delusion that a single individual can save us from ourselves.

References

Stephen Holmes. 1995. Passions and Constraint: On the Theory of Liberal Democracy. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Machiavelli, N., 1988, The Prince, Q. Skinner and R. Price (eds.), Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

____________. The Discourses. Translated by Leslie J. Walker, S.J, revisions by Brian Richardson (2003). London: Penguin Books.

Robert Michels. 1911 (1915 trans). Political Parties: a Sociological Study of the Oligarchical Tendencies of Modern Democracy. University of Virginia Electronic Text Center.

Sydney Verba. 1961. Small Groups and Political Behavior: A Study of Leadership. Princeton: Princeton University Press.